“Yearn for the Urn”: How Gen Z and Millennials Use Dark Humor on TikTok to Cope, Connect, and Perform Identity:

Fiona DeFrance, Monique Love, China Porter, Shriya Shekatkar, Lu Zhang

If you’ve ever laughed at a meme about depression and then paused to wonder if you were supposed to, you’re not alone. For Gen Z and Millennials, dark humor isn’t just a way to be funny, it is a form of emotional expression, identity work, and social bonding. On TikTok, this type of humor has taken on a life of its own, acting as both a coping mechanism and cultural signal. This blog will explore how these two generations use dark humor differently. Millennials, shaped by MySpace sarcasm and Adult Swim absurdity, tend to use humor to distance themselves from discomfort. Gen Z, on the other hand, often lean into it, using irony, vulnerability, and meme culture to face trauma head on. By analyzing patterns in TikTok videos, including the language people use, their emotional tone, and how viewers respond, we uncover how dark humor works as a powerful tool for navigating life’s messiness. Drawing on sociolinguistic theory (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005) and humor research (Samson & Gross, 2014), we show how generational identity, emotion, and community are shaped by digital jokes, and why they’re more meaningful than they might seem at first.

Introduction and Background

Why Joke About Trauma?

What does it mean when a TikTok about grief racks up millions of likes? Or when a stitched joke about student debt leads to hundreds of people commenting, “Too real?” For Gen Z and Millennials, dark humor, jokes that deal with death, anxiety, trauma, or mental health, is not just comedy. It’s a language of solidarity. It’s a way to say, “I’ve been there too,” without getting too earnest or heavy-handed. It’s not about making fun of pain, it’s about making pain bearable by laughing through it. What’s striking, however, is that while both generations lean into this humor, they do so in different ways. Millennials often rely on sarcasm and absurdity to create emotional distance from the discomfort they feel. Their humor is layered, witty, and steeped in cultural references. Gen Z, on the other hand, tends to blend irony and sincerity, using dark humor as a way to be publicly vulnerable, often self-deprecating, chaotic, and confessional. These differences are deeply tied to each generation’s coming of age context and their digital fluency. This blog investigates how these generational styles of dark humor reflect broader identity performances on TikTok. We argue that this humor is a powerful communication tool for expressing emotion, belonging, and generational identity. Through an analysis of both videos and comment threads, we explore how people use humor not just to entertain, but to cope and connect.

Same Joke, Different Vibe

Millennials, born between 1980 and 1994, were the first generation to grow up alongside the internet. Their humor was shaped by platforms like Tumblr, Reddit, and meme forums, where sarcasm, nihilism, and absurdism flourished. Broderick (2018) describes Millennial humor as “cultural therapy,” often used to intellectualize or distance oneself from emotional discomfort. Shows like Rick and Morty capture this smart, ironic, and deeply existential tone. Gen Z, born between 1995 and 2012, came of age in a digital world shaped by Instagram, Vine, and especially TikTok. Their humor style is faster, more fragmented, and more openly vulnerable. Jacob (2023) describes Gen Z humor as a “performance of authenticity,” in which users lean into self-mockery and emotional chaos to show relatability. Instead of hiding pain under wit, Gen Z often makes the pain itself the joke. This shift can be understood through the sociolinguistic lens of Bucholtz and Hall (2005), who argue that identity is not fixed but constantly performed through language and interaction. On TikTok, dark humor becomes a discursive tool, a way to perform who you are and to whom you belong. A single comment like “same bestie 😭” signals not just shared feelings, but shared values and generational belonging.

Methods

What We Watched and How We Looked

To explore how dark humor operates differently across generations, we conducted a qualitative analysis of 10 TikTok videos that shared themes of trauma, grief, or existential dread. We chose videos that had hashtags like #genzhumor, #millennialhumor, #traumajokes, and #griefjourney to ensure generational and thematic diversity. These videos ranged from ironic skits to darkly humorous storytimes. From these 10 videos, we collected and analyzed a total of 236 top level comments. We coded the comments using several frameworks, humor type based on Samson & Gross (2014), emotional tone, generational markers, and linguistic style. We looked for common humor strategies, such as self-deprecation, irony, absurdism, or sarcasm, and also examined how emoji usage, slang, and hashtags helped signal generational identity and emotional intent. Rather than analyzing the content of the videos alone, we focused heavily on how users engaged with them in the comments. These interactions revealed how humor becomes collaborative, social, and identity-forming.

Results and Analysis

Patterns in Digital Dark Humor

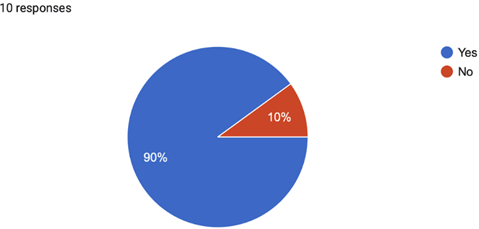

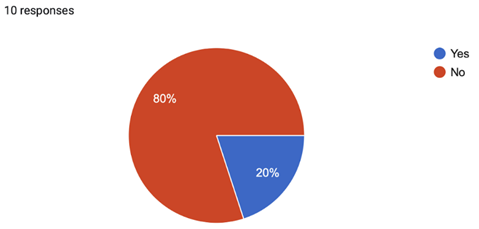

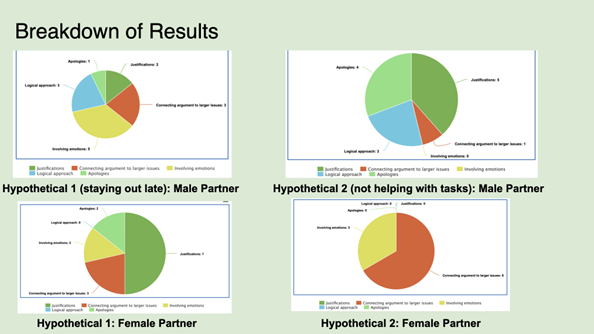

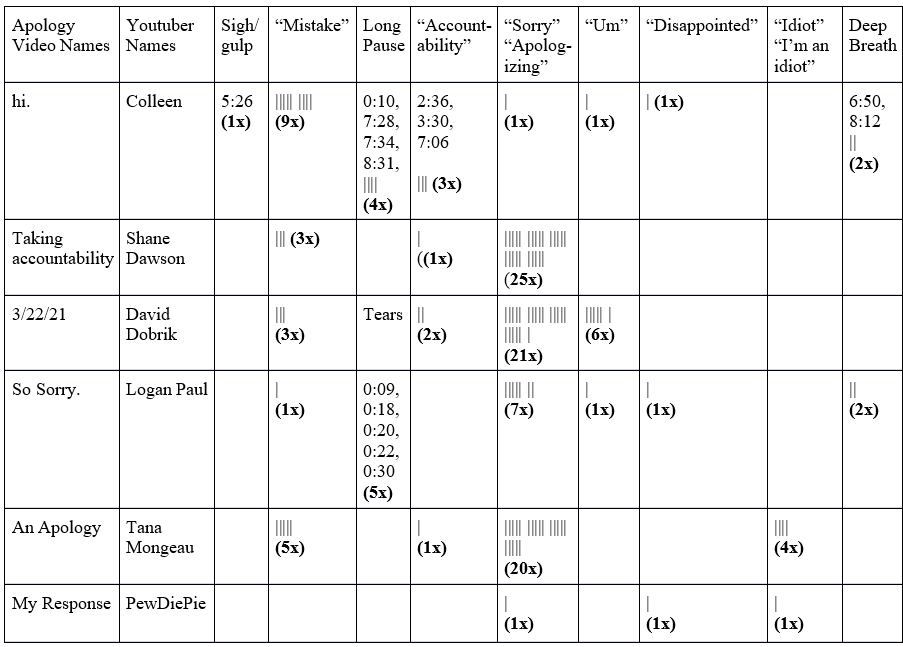

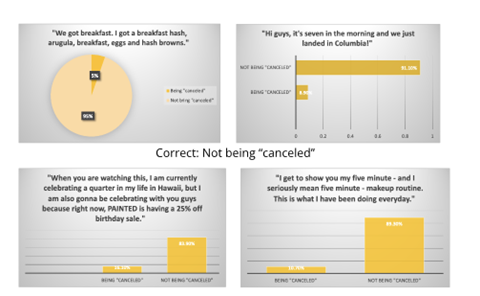

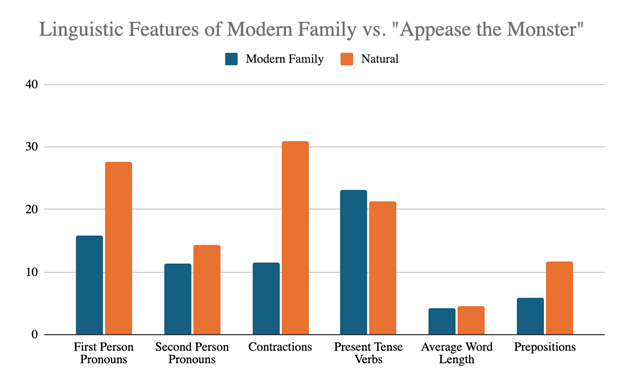

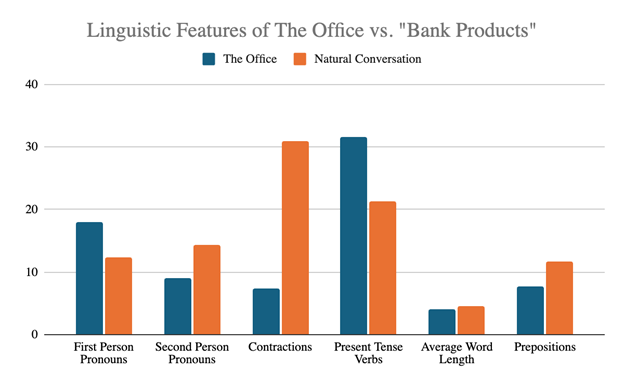

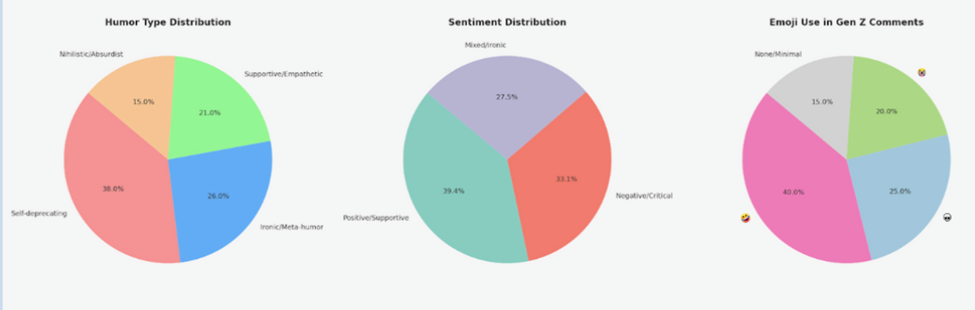

Across our sample, four major humor categories emerged. First, self-deprecating humor was the most common, accounting for 38% of comments. These included phrases like “crave the grave,” “I’m not laughing, I’m relating,” and “literally me 😭.” (See Figure 2, Humor Type Distribution). Next, ironic and meta-humor made up 26% of the comments, often blending sarcasm and detachment, such as “ghosting over a joke is crazy 💔” or “me laughing at this while sobbing IRL.” Supportive or emotionally affirming comments made up 21%, often taking the form of gentle validation like “she would’ve loved this” or “sending hugs to anyone who gets it.” Finally, nihilistic or absurd humor made up the remaining 15%, marked by comments like “damn again?” or “just another Tuesday in hell.” (See Figure 2).Looking more closely at generational patterns, we found that Gen Z-coded comments (n = 120) were typically short, fast-paced, and emotionally raw. Commenters used emojis like 🥲💀😭 to intensify their tone, often stacking them for emphasis. Phrases like “same bestie” and “real for that” appeared frequently, offering micro-validations that signaled both empathy and in-group belonging. This aligns with the high rate of emoji use seen in Gen Z comments (See Figure 2, Emoji Use in Gen Z Comments). Gen Z’s humor, which was deeply communal, inviting others to share in the emotional experience. Millennial-coded comments (n = 116), in contrast, were more likely to be narrative-driven. Users told short anecdotes or crafted witty one-liners like, “I screamed into my Trader Joe’s tote bag after watching this.” These comments often featured cultural references, dry sarcasm, or a clear setup-punchline structure. Emoji use was minimal, and tone leaned toward ironic detachment. This generational contrast is further illustrated in Figure 1, which shows Millennials using sarcasm more frequently and Gen Z relying more heavily on self-deprecation. Sentiment analysis revealed that 39% of all comments were supportive, 33% were negative or critical, and 28% blended irony with sincerity. (See Figure 2, Sentiment Distribution)These findings echo Van der Wal et al. (2022), who argue that humor can serve social regulation and bonding functions. On TikTok, we see this in real-time: a grieving user posts a dark joke, and strangers respond with humor, empathy, or shared experience, creating a temporary but powerful moment of digital solidarity.

Discussion and Conclusion

If you really want to understand how young people cope with stress, loss, and mental health struggles, look past the punchline and into the comments. That’s where the real conversations happen. When a Gen Z user jokes about grief and someone replies “too real 🫠,” it’s not just a laugh, it’s an act of recognition. It says, “I get it. I’ve been there too.” For Millennials, telling a deadpan story about a panic attack on public transit isn’t just entertainment, it’s emotional processing disguised as comedy. What’s especially fascinating is how these generational styles also create boundaries, both of inclusion and exclusion. When someone from outside the in-group comments, “This isn’t funny,” Gen Z users often respond with layered irony or dismissive humor, reinforcing the communal tone of “if you know, you know.” Millennials might disengage or reply with a witty retort, maintaining their signature emotional distance. These micro-interactions show how humor doesn’t just express identity, it defines who’s in and who’s out. Ultimately, these humor styles reveal how differently each generation experiences and narrates vulnerability. Gen Z foregrounds emotional chaos and authenticity. Millennials lean on cleverness and control. Both, however, are trying to do the same thing: make sense of a world that often feels senseless. And in doing so, they build digital spaces where humor becomes survival, and connection.

If you really want to understand how young people cope with stress, loss, and mental health struggles, look past the punchline and into the comments. That’s where the real conversations happen. When a Gen Z user jokes about grief and someone replies “too real 🫠,” it’s not just a laugh, it’s an act of recognition. It says, “I get it. I’ve been there too.” For Millennials, telling a deadpan story about a panic attack on public transit isn’t just entertainment, it’s emotional processing disguised as comedy. What’s especially fascinating is how these generational styles also create boundaries, both of inclusion and exclusion. When someone from outside the in-group comments, “This isn’t funny,” Gen Z users often respond with layered irony or dismissive humor, reinforcing the communal tone of “if you know, you know.” Millennials might disengage or reply with a witty retort, maintaining their signature emotional distance. These micro-interactions show how humor doesn’t just express identity, it defines who’s in and who’s out. Ultimately, these humor styles reveal how differently each generation experiences and narrates vulnerability. Gen Z foregrounds emotional chaos and authenticity. Millennials lean on cleverness and control. Both, however, are trying to do the same thing: make sense of a world that often feels senseless. And in doing so, they build digital spaces where humor becomes survival, and connection.

Figure 1: Sentiment and Humor Type Breakdown with Gen Z Emoji Use This set of pie charts presents three types of analysis from TikTok dark humor comments. Left: Humor Type Distribution—shows the proportion of humor types (Self-deprecating, Ironic/Meta, Supportive, Nihilistic/Absurdist). Middle: Sentiment Distribution—illustrates the emotional tone across comments (Positive/Supportive, Mixed/Ironic, Negative/Critical).Right: Emoji Use in Gen Z Comments—displays how frequently and in what style emojis appear, with 40% of comments using exaggerated or emotional emojis (e.g., 🤣😭💀), reinforcing Gen Z’s preference for hyperbolic and affective expression.

Figure 2: Comment Style Breakdown by Generation

This bar graph compares the comment styles used by Gen Z and Millennials in TikTok dark humor content. The x-axis shows the three main comment styles (Self-deprecating, Sarcasm, and Empathetic), while the y-axis represents the percentage of total comments in each style. Gen Z (blue) shows a higher rate of self-deprecating and empathetic comments, while Millennials (green) use more sarcasm overall

References

Broderick, A. E. (2018). ” Traumatized for Breakfast:” Why Millennials Respond to the Trauma, Comedy, and Dark Optimism of Rick and Morty. State University of New York at Stony Brook. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2138913981?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse studies, 7(4-5), 585-614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407

Jacob, R. (2023) Unveiling the Dark Humour and Self-Image of Generation Z in a Polymedia Context. The Criterion: An International Journal in English, 14, 215-26. [Journal-article]. https://www.the-criterion.com/V14/n4/LL07.pdf

Samson, A. C., & Gross, J. J. (2014). The dark and light sides of humor. Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides, 169. https://books.google.com/bookshl=en&lr=&id=1vNQEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA169&dq=how+dark+humor+operates+in+different+contexts+and+what+social+function+it+serves&ots=oJgSRN9EGw&sig=m4AO3FgFdMIjLutcRkYGcT8fh8#v=onepage&q=how%20dark%20humor%20operates%20in%20different%20contexts%20and%20what%20social%20function%20it%20serves&f=false

Van der Wal, A., Pouwels, J. L., Piotrowski, J. T., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2022). Just a Joke? Adolescents’ Preferences for Humor in Media Entertainment and Real-Life Aggression. Media psychology, 25(6), 797–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2080710