The Language of Love: Gendered Communication Patterns in Conflict

Analisa Sack, Paden Frye, Olivia Simons, Stella Kang, Jeorgette Cuellar

Our study explores the differences in how men and women express emotions in heterosexual relationships, particularly during conflict situations. The research investigates language dynamics among college-aged couples. Hypothetical conflict scenarios were used to elicit natural responses, which we then transcribed and analyzed. The findings reveal that women are more likely to use emotive language, engage in expressive communication, and employ collaborative discourse strategies during conflicts. In contrast, men tend to use direct communication styles, focusing on factual components and solution-oriented language. These results align with existing research on gendered communication patterns, supporting the hypothesis that media portrayals of emotional women and logical men have a basis in reality. This study underscores the importance of understanding gender-specific communication styles, offering insights that can enhance relationship counseling and educational programs. Future research directions include cross-cultural studies and longitudinal analyses to further explore these dynamics. The implications of this research are significant for developing tailored communication strategies in both personal and professional contexts.

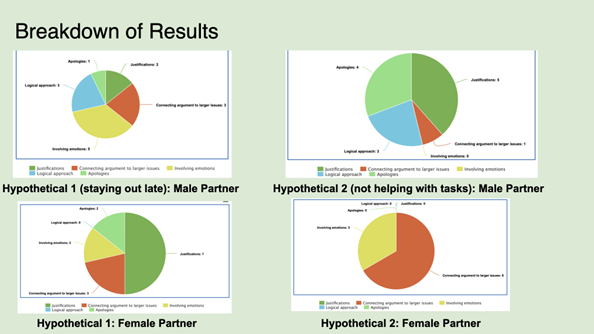

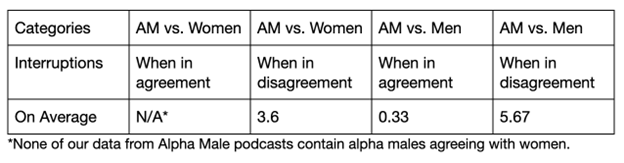

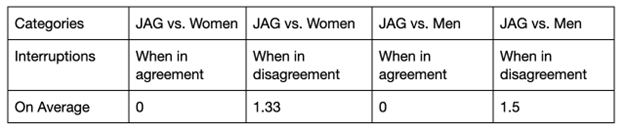

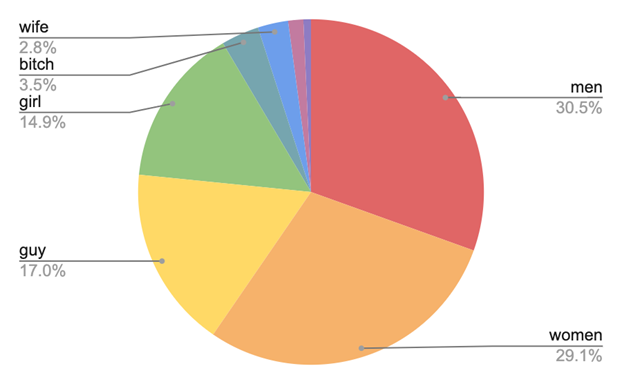

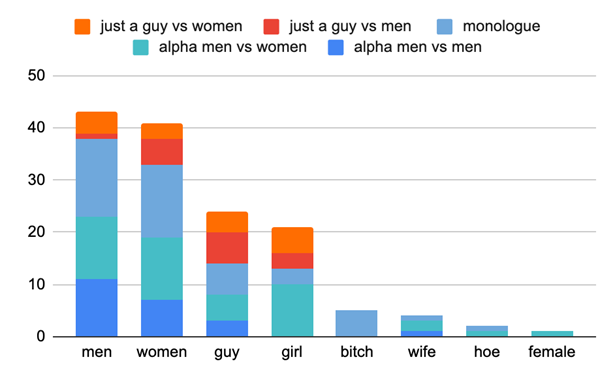

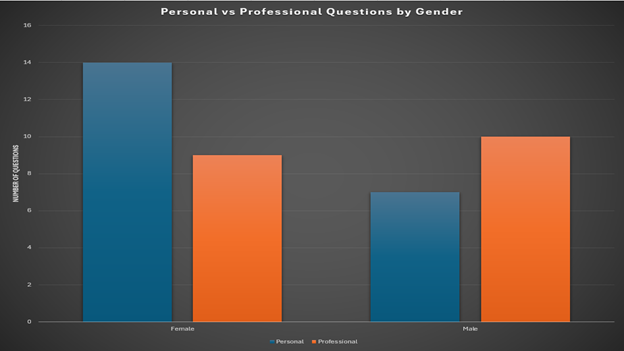

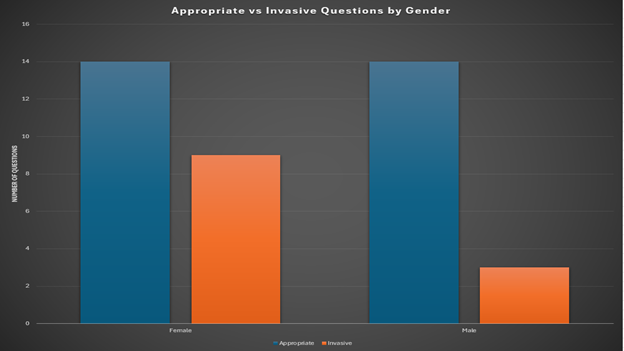

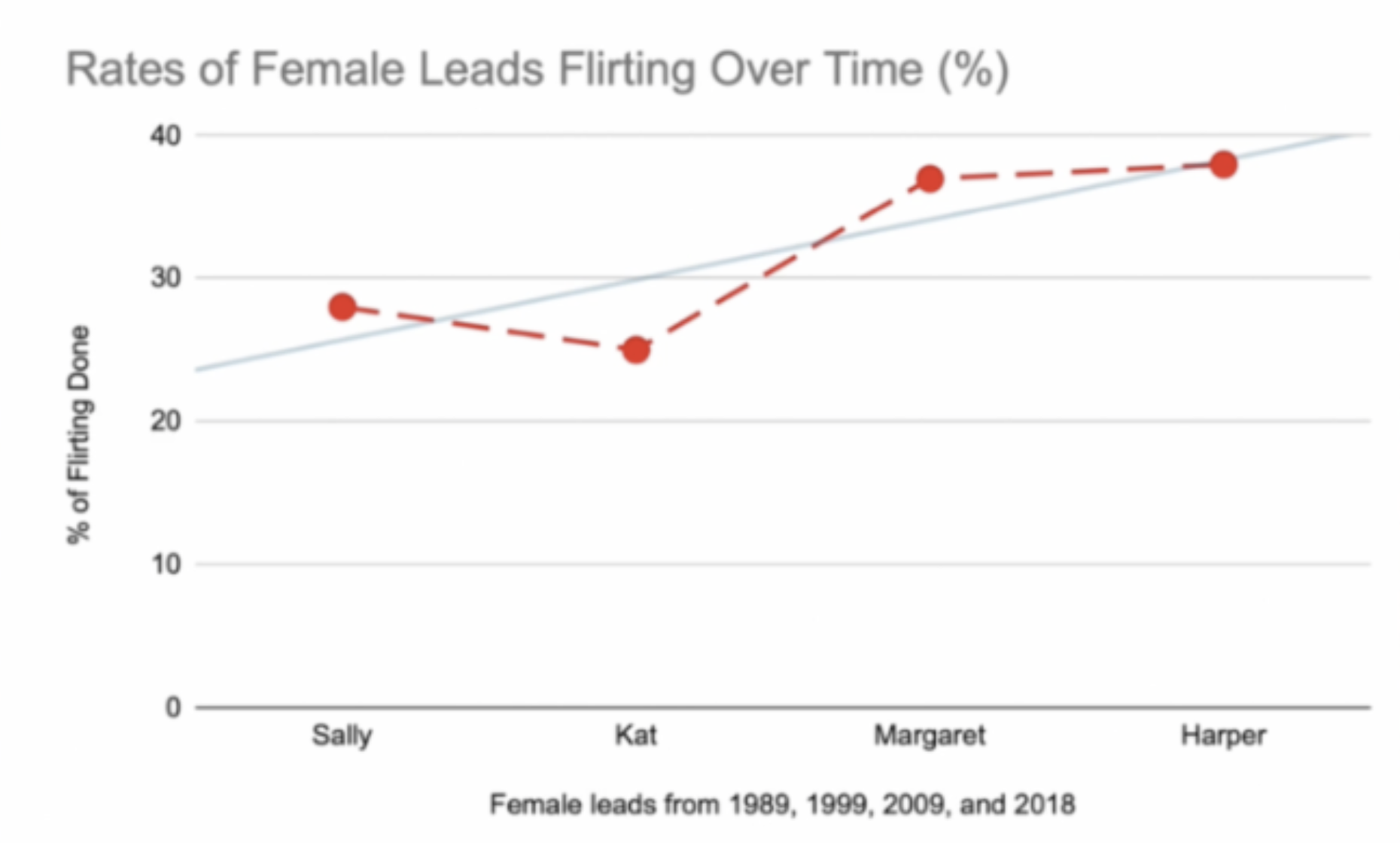

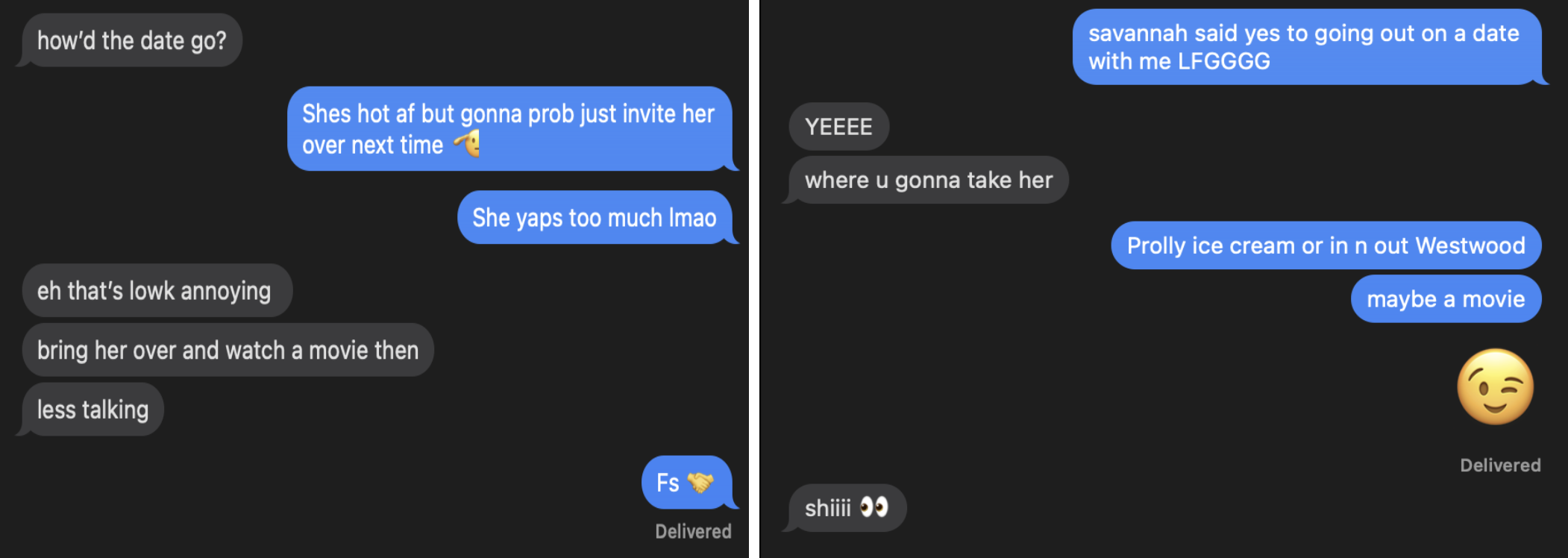

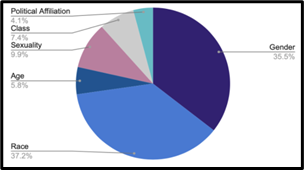

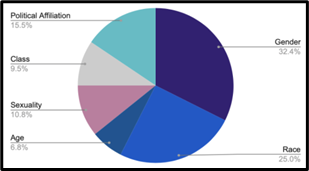

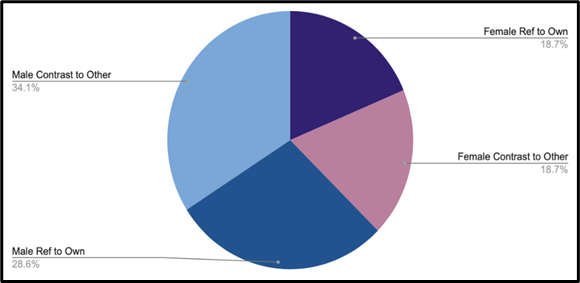

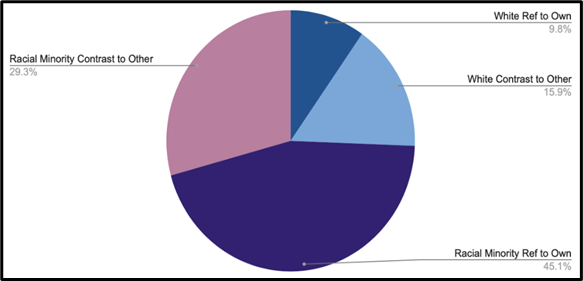

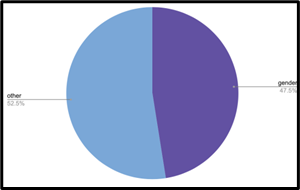

Introduction and Background We aim to investigate language dynamics and patterns within college-aged heterosexual relationships. With a specific focus on conversation, conflict, and conflict resolution. Communication styles in relationships affect conflict resolution and relational satisfaction. Prior studies have shown differences in male and female communication styles, but specific lexical patterns and their impact on conflict resolution are underexplored. We chose college-aged heterosexual relationships because this age group is shown to be especially important as shown in a study done by Sprecher (1993); typically, we see this age undergoing key developmental transitions and experiencing many situations that may be emotionally or relationally challenging. This study will analyze lexical patterns in conversations to understand gender dynamics in conflict resolution. We hypothesize that during conflict in heterosexual relationships, women are more likely than men to use emotive language, engage in expressive communication, and employ collaborative discourse strategies during conflict resolution, whereas men are more likely to use direct and assertive communication styles, focusing more on factual components of the situation and solution-oriented terms of speech. Regarding social structures within college-aged relationships, previous research has suggested women are more emotionally active in relationships, but little applicable research has actually shown this. While women have expressed the consistency in emotions experienced being high, their expression of these emotions isn’t necessarily higher than that of men. Our study aimed to understand how men and women approach conflict resolution by looking at word choice and language use in particular (conversation analysis), evaluating how men and women use language differently to approach conflict. The language aspect we are examining is word choice (lexicon) and interaction patterns (conversation analysis) – more specifically, the use or lack of emotive language and expressive communication (Rogers, Ha, Byon, & Thomas, 2020, p. 112). Methods In order to collect relevant results, we thought it would be best to observe couples resolving a “natural” conflict. Since it would be nearly impossible to follow a couple around and wait for them to have a fight, we thought our best option would be to simulate a conflict and ask the couple to react to each other the way they would in real life. We understand and acknowledge that this might present flaws in our data due to self-reporting bias, where people tend to try making themselves seem “better” than they are in reality. Nevertheless, these are the hypothetical situations we presented: After we conducted the interviews, we analyzed the transcripts by deciding on five categories that best summed up the strategies the two participants used. These categories included justifications, connecting the argument to larger issues in the relationship, involving emotions, using logical approaches, and apologizing. We decided on a standardized way to tag parts of the dialogue with each strategy and then counted each instance of each strategy for both partners in both hypotheticals. We then created pie charts to visualize our data for both partners in both hypotheticals. Results and Analysis The most common strategy used by the female partner was connecting the argument to larger issues in the relationship, followed by justifications and involving emotions. For the male partner, justifications came first, followed by using a logical approach and apologizing. After conducting controlled experiments with the implementation of two separate hypothetical situations to heterosexual college couples, it was observed that male partners exercise direct response tactics more often than females and utilize logical reasoning along with factual references in order to strengthen their argument, while also digressing at moments in order to avoid further conflict or off-track arguments. Previous studies have hypothesized that a woman’s willingness to exceed only factual comments in arguments is due to their lack of power or control in the outside world and their desire to hold more control in intimate spaces. Female partners tended to use open questions and emotive language very often, expressing their feelings. Although initial questions were presented when initiating conflict resolution strategies, there were never any direct solutions posed by the female partner. Female participants also expressed a wider range of emotions, including anger, sadness, confusion, and disbelief during the conversation. Vocally, our female participant also had more shifts in tone – explicitly in words used – and differences in pitch depending on the emotions she felt at the moment. The female participant also related current conflict with previous situations where her feelings and overall well-being were disregarded, and she was forced into performing more emotionally/physically labor to make up for her partner’s negligence. Our findings were in line with the article “Gender Differences in Perceptions of Emotionality” by Susan Sprecher used as background for the study, specifically with the idea that men will not argue as emotionally or as long as women do and tend to discuss conflicting topics without extreme emotion. We hypothesized these would be our result but ultimately gained a better understanding of the psychodynamic difference of the male versus female resolution strategy through the article’s in-depth observations. Discussion and Conclusions In conclusion, our hypothesis was supported by the findings of our study. We observed differences in communication during conflict resolution within heterosexual relationships. Women were more inclined to use more emotive language, characterized by a higher frequency of elements such as tag questions. This aligns with Robin Lakoff’s observations in “Language and Woman’s Place,” where tag questions – phrases like “isn’t it?” or “right?” added to the end of statements – serve to invite confirmation or agreement, thereby fostering a more inclusive and collaborative dialogue (Lakoff 54). In our research, women used tag questions seven times compared to men’s two instances. For example, in Hypothetical 1, a woman asked, “Do you trust me or my friend’s stories?” (F, 02:18), illustrating the use of tag questions to engage the listener. Conversely, men demonstrated a tendency toward a more direct communication style, often employing justifications. This logical approach focuses on explaining actions or decisions assertively. For instance, in Hypothetical 2, a man stated: “You usually just want to do stuff your own way because if I do something my way, you don’t like the way it’s done” (M, 00:49). This directness reflects a more frequent use of logical elements in his communication, aimed at justifying perspectives or actions. Further, our results are in alignment with studies done about typical communication style differences in gender. In the article “Gender Issues: Communication Differences in Interpersonal Relationships” from Ohio State University, we learn that society has a general understanding of women having to ‘read between the lines’ in relationships: “Studies indicate that women, to a greater extent than men, are sensitive to the interpersonal meanings that lie ‘between the lines’ in the messages they exchange with their mates. That is, societal expectations often make women responsible for regulating intimacy, or how close they allow others to come” (Torppa). As we concluded from our own research, it appears that women are more inclined to connect a specific argument to the larger scope of the relationship. When something brought up in conflict triggers a larger, recurring issue, the female partner is likely to open up the conversation to what she can see by ‘reading between the lines.’ According to research done by Jessica Cindaro regarding male and female differences in communicating conflict, prior literature suggests a tendency for women to be more emotive in their communication styles, while men tend to be more direct and assertive, using emotions less. Cindaro explains that this is in part because of gender stereotypes and the environment in which men and women are raised in and the messages they receive growing up about how best to communicate (Cindaro). We see in our results that there is an even distribution involving emotions, but that the male partner takes more of a logical approach more often than the female partner. These findings underscore the distinct communication styles of men and women, and such insights can be valuable in enhancing communication strategies across various contexts, from personal relationships to professional interactions. Also, by providing deeper insights into how communication styles differ between genders, our findings can inform relationship counseling and therapy practices, allowing therapists to develop more effective strategies that are tailored to each gender. This improved understanding can contribute to better communication and conflict resolution within relationships, ultimately supporting potentially healthier interpersonal dynamics. In the future, our research aims to open avenues for expanding the scope of study. One possible direction is conducting cross-cultural studies to investigate whether the communication patterns we observed are consistent across different cultural contexts or if they vary significantly. This would provide a broader understanding of how cultural influences shape gender communication styles. Additionally, we could undertake longitudinal studies to track how communication styles and conflict resolution strategies evolve over time within relationships. These long-term studies can offer deeper insights into the dynamics of long-term relationships, shedding light on how communication evolves and how couples adapt their conflict resolution strategies over the years. Another question that might be brought up in relation to our study is one of media’s influence on a person’s gender identity. In the TED Talk “Secrets of Children’s Media: Effects of Gender Stereotypes,” Rifa Momin reveals that children are influenced by the stereotypes they continuously hear as they grow up. From children’s television to storybooks, the power of media influence contributes to “children developing a sense of maleness and femaleness based off of these stereotypes and organiz[ing] their behaviors around them” (Momin). This presents a bigger question about our research: Do the stereotypes we perceive men and women to inhabit originate from their media intake? If children were not exposed to media that perpetuates gender stereotypes, would they grow up to act differently than the way society has led us to believe we’re ‘inclined’ to act? Overall, the study we have conducted opens a wide variety of discussion topics regarding gender stereotypes, communication styles, and conflict within heterosexual college-aged relationships. While our study is not reflective of every single relationship out there, we hope we accomplished our goal of sparking conversation to further understanding about why men and women communicate differently. References Cinardo, J, (2011) Male and Female Differences in Communicating Conflict. Honors Theses. 88. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/88. Lakoff, R. (1973). Stanford. Language and Woman’s Place. https://web.stanford.edu/class/linguist156/Lakoff_1973.pdf. Momin, R. (2022, March). Secrets of children’s media: Effects of gender stereotypes. Rifa Momin: Secrets of Children’s Media: Effects of Gender Stereotypes | TED Talk. https://www.ted.com/talks/rifa_momin_secrets_of_children_s_media_effects_of_gender_stereotypes?language=en. Rogers, A. A., Ha, T., Byon, J., & Thomas, C. (2020). Masculine gender‐role adherence indicates conflict resolution patterns in heterosexual adolescent couples: A dyadic, observational study. Journal of Adolescence, 79(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.004. Sprecher, Susan. Sexuality. SAGE Publications Inc., 1993. Sprecher, S., & Sedikides, C. (2019, August 14). Gender differences in perceptions of emotionality: The case of close heterosexual relationships – sex roles. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00289678. Torppa, C. B. (2010, February 25). Gender issues: Communication differences in interpersonal relationships. Ohioline. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/FLM-FS-4-02-R10.