Heritage Language, Linguistic Proximity Model, Language Learning Heritage Speakers and L3 Learning: Impacts on New Language Development

Victoria Sauceda, Remi Akopians, Elizabeth Escamilla, Stella Kang

Why do some languages feel easier to learn than others? For heritage speakers or individuals who grow up speaking a minority language at home while navigating the dominant language of their community, acquiring a third language (L3) comes with its own set of challenges and benefits. This study investigates whether linguistic proximity between languages makes L3 acquisition easier, focusing on Spanish heritage speakers who are learning either Parisian French, a close Romance language, or Seoul Korean, a linguistically distant language in the Koreanic language family.

Our research study examines phonetics, particularly vowel perception, to explore how proximity among language families influences language learning. In the listening comprehension methodology this study employs, participants who identified as Spanish heritage speakers and beginner or intermediate learners of French or Korean were instructed to identify shared vowels such as /a/, /i/, /o/, /u/ in all three languages or Spanish, French, and Korean. If one group had a higher accuracy percentage in identifying more of these vowels than the other, this finding could indicate that certain factors, such as linguistic proximity play an important role in learning a third language. Overall, this blog builds on these findings to explore their implications for understanding heritage speakers’ third-language acquisition experience.

Introduction and Background

Heritage learners navigate the cross-section between their home language and the dominant language in their broader societal environment, providing a unique perspective on multilingualism. A heritage learner is typically an individual raised in a household where a language other than the societal majority language is spoken, leading to high proficiency levels in both languages. Unlike general multilingual individuals, heritage learners often experience imbalanced exposure to their languages due to the switch to another dominant language, influencing their learning trajectory.

The research investigates the differences between acquiring a third language within the same language family and learning a language from a distinct family, focusing on Spanish heritage speakers. It examines the experiences of Mexican Spanish speakers who have acquired English as their second language and they are now learning Parisian French compared to Seoul Korean which is part of the koreanic family. The research aims to understand how heritage speakers handle multilingualism and the linguistic and cognitive elements influencing language acquisition outcomes.

We know that a heritage speaker can be someone who grows up speaking a minority language at home while being exposed to the dominant language in their community. Research on heritage language speakers suggests early exposure to a minority language has a major impact on their linguistic and cognitive abilities when compared to monolinguals and second-language learners. According to Westergaard’s (2016) findings, which support the Linguistic Proximity Model (LPM), both previously acquired languages impact subsequent L3 acquisition, implying that structural similarity is an important aspect in third language learning. In a more recent study, Deng (2022) analyzed the comprehensibility of tone 3 sandhi production between Mandarin and Cantonese heritage learners and non-heritage learners and found no significant differences.

These studies and researchers provide an understanding of how past linguistic knowledge influences language acquisition. The final study I will discuss supports and complements the two previous ones presented even though it is more focused on grammar, sentence structure, and production. Hopp’s (2014) study compares Turkish-German bilingual children with German monolingual children studying English as a third language to investigate the study of cross- linguistic influence on grammar. Why Hopp(2014) found regarding cross linguistics how the bilingual group’s English grammar learning was impacted by their first and second languages with the impact differing depending on the common linguistic elements. With this, we see Hopp(2014) supports Westgaard(2016) by emphasizing that cross-linguistic impact is influenced by structural similarities and language dominance which align with the LPM model.

Deng (2022) focuses on how heritage learners’ linguistic memories impact their ability to learn phonological rules, providing an in-depth assessment of specific learning challenges. Westgard (2016)gives a larger approach highlighting the importance of linguistic proximity and selective transfer in defining how learners apply their past language skills. Their study shows the ways that past linguistic exposure impacts the process of learning new languages. Examining these prior studies offers an outline of ideas, methods, and evidence that help guide the development and execution of our research.

Methods

To investigate whether Spanish heritage speakers find it easier to acquire a third language (L3) within the same language family, we conducted a phonetics-focused study comparing participants learning French, a Romance language, and Korean, a Koreanic language. In the process of gathering participants, we reached out to professors and teaching assistants in the French and Korean departments within institutions such as UCLA who distributed our survey to Korean and French learners in their class who were Spanish heritage speakers. Participants included a total of eleven participants, six Spanish heritage speakers acquiring French and five Spanish heritage speakers acquiring Korean, all at beginner or intermediate proficiency levels. Due to our limited time and Thanksgiving break overlapping with our outreach, we decided to reach out to the Spanish club and extended our research group to include intermediate speakers; this gave us the last few participants we needed. The Google form starts with qualitative questions to gather data on the participant’s proficiency and the languages they speak. Knowing the participants’ proficiency in potential languages allowed the ability to exclude participants that would result in confounding data.

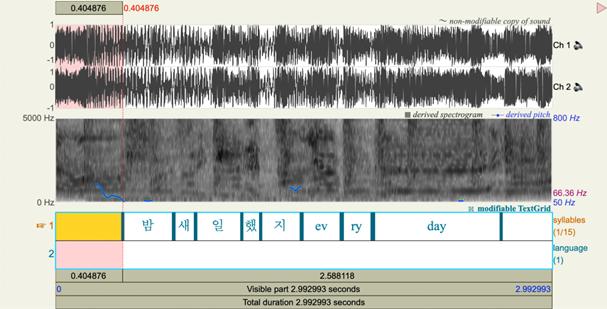

We tested our hypothesis by experimenting using a listening comprehension methodology that measures the accuracy of a participant’s phonetic perception of sounds in their third acquired language of French or Korean. Consequently, the focus of this experiment was phonetics, and as a result, we examined how vowel perception has the potential to be under the influence of proximity among linguistic families. We utilized this methodology to compare the accuracy percentage of French, a language in the same Romance language family as Spanish, and Korean, a language from the Koreanic language family that is unrelated to Spanish. In the experiment, the participants completed a listening comprehension task by listening to recorded words from their respective L3s. Data was collected via Google Forms, with audio stimuli being produced through IPA reader for our French survey and recorded by a native Korean speaker for the Korean survey. The French survey tested five words and the Korean survey tested seven words, such as “dans” for French and “바다” for Korean, both containing the same shared vowel with Spanish, /a/. The participants were then instructed to manually type in what sounds they heard and were given a list of all vowels in their respective languages to choose from. During the listening comprehension task, the participants identified vowel sounds in the French or Korean words to assess their ability to identify the same vowel sounds in their respective L3. The vowels analyzed include shared sounds such as /a/, /i/, /e/, and /o/ for French and Spanish, and Korean vowels such as /a/, /u/ and /o/.

After collecting responses from respective participants, responses were analyzed for accuracy to determine whether linguistic proximity between L1 and L3 facilitated phonetic perception. By calculating the ratio of accurately identified vowels to the total number of questions and multiplying the quotient by one hundred, we were able to calculate the accuracy percentage for each survey. To compare the average accuracy between the French and Korean surveys, we took the mean scores of both surveys, accounting for all participants. Depending on the comparative accuracy percentages, we sought to assess whether linguistic proximity, such as French and Spanish in the Romance language family, provided an advantage over unrelated language pairs, such as Spanish and Korean from the Koreanic language family.

Results and Analysis

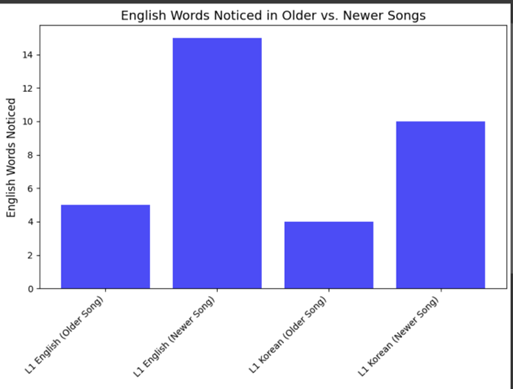

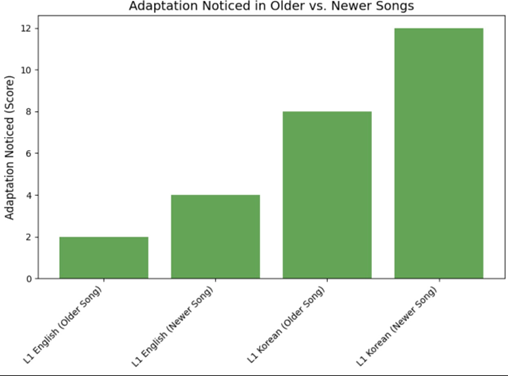

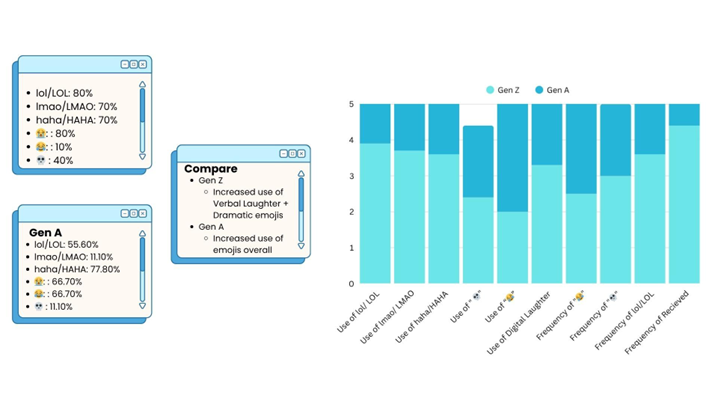

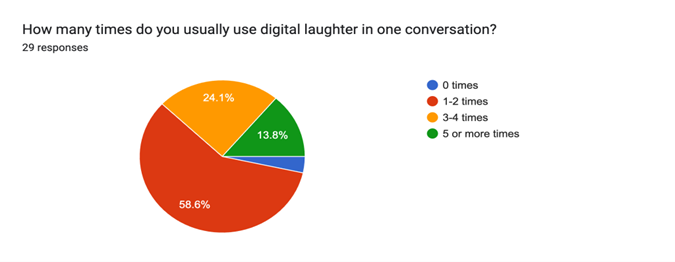

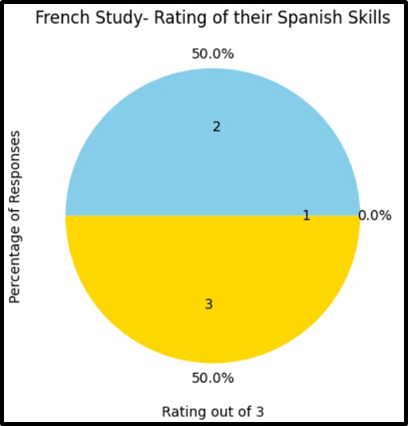

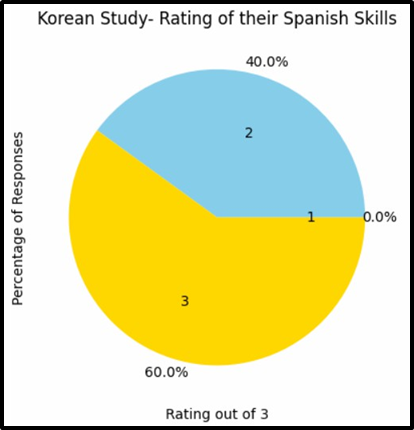

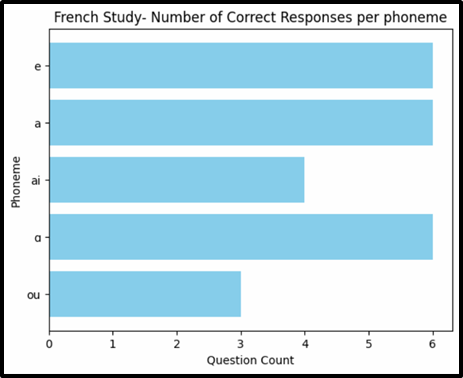

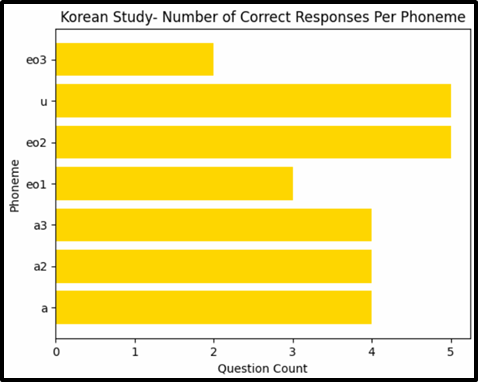

Analysis was conducted based on the participants’ accuracy in the listening comprehension task. We were able to recruit 11 participants: six French L3 learners and 5 Korean L3 learners. Surprisingly, we found that the results did not confirm our hypothesis, which stated that learning a third language within the same family is simpler and quicker for heritage Spanish speakers. Instead, we found that Korean learners performed with slightly better margins on the phonetic vowel listening task, acquiring an 87.5% accuracy, and French learners acquired an 83.3% accuracy overall. Contrary to our predictions and proposed hypothesis, these results indicate no notable advantage was observed on the impact of one’s heritage language on their L3 acquisition. The participants showed no significant benefit in their L3 acquisition of French or Korean by having acquired Spanish as a heritage language. Our intuition was that the participants would do better with French than Korean given that Spanish and French are derived from the same language family.

However, it is difficult to generalize these results to a larger population because the study did encounter setbacks that may have affected our findings. First and foremost, we had a very limited sample size. At the time of this study, we were able to reach out to various beginner and intermediate-level language courses at UCLA in French and Korean for participants, but given the specificity of our subject requirements, it was difficult to find individuals who qualified for the study. Second, we were under strict time constraints. While most research projects are able to go on for an indefinite amount of time, we had a little under 10 weeks to research and design our study, create the experiment, find participants, and run data analysis. Lastly, we were unable to use our preferred experimental software, Gorilla, due to lack of funding, so we opted for a Google form survey.

Originally we were inspired to study the connection between learning a new language and a person’s heritage language. We chose Spanish speakers in hopes of broadening our sample size. Attending university in Los Angeles, we knew we would have the most luck finding Spanish heritage speakers and having access to UCLA’s diverse student body aided in our search. In the future, we would like to examine more language families and increase our sample size to acquire a larger amount of data. We would also like to extend our research from its current focus on phonetics and explore the impact of heritage languages on the syntax, morphology, or pragmatics of other acquired languages. We felt phonetics was the best place to start because we knew we would eventually be reaching out to introductory-level language courses in French and Korean for volunteers. Phonetics is the basis of all languages and is the focus of most beginner classes, so for this reason, we chose to test the participants utilizing vowels. This guaranteed the participants had been properly exposed to sounds similar to our stimuli. While our results were not what was expected, in the future, we would like to see if these same results are consistent for morphology, syntax, pragmatics, or within other language families. To expand the study, it would be beneficial to expand syntactic data by testing the participants with questions that focus on grammar. This would allow us to see if differing grammar rules has an affect on the participants’ performance. Languages can be from the same word family and have a different word order. Some languages can even have more than one word order. Would knowing Spanish be beneficial or would it lead to more error if the participant is learning a language with a completely different word order. Similarly, morphology could be used to further the study and test if the relationship is different for morphology versus phonetics and syntax. The participants could be tested on affixes across languages. Many suffixes and prefixes are borrowed from other languages and so both French and Korean participants could be asked to identify affixes that are found in Spanish and in French and Korean. The results could show us if knowing Spanish is beneficial to identifying definitions even when the root of the word is not found in Spanish.

Visuals for Results Section:

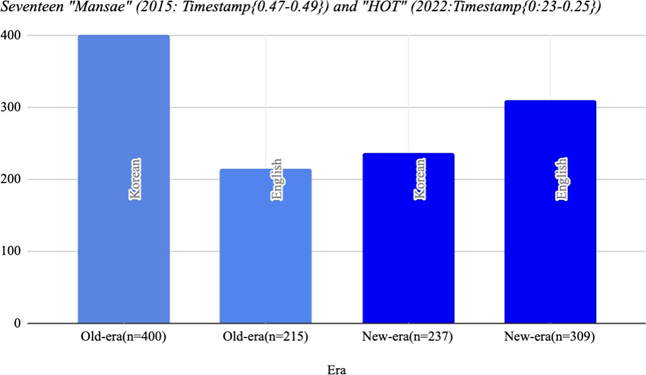

Figure 1: Participants rated their proficiency in Spanish

Figure 2: Participants rated their proficiency in Spanish

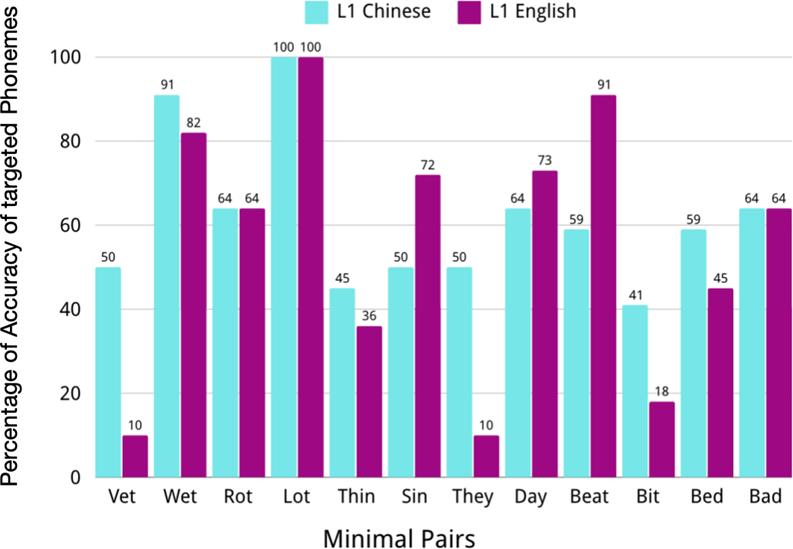

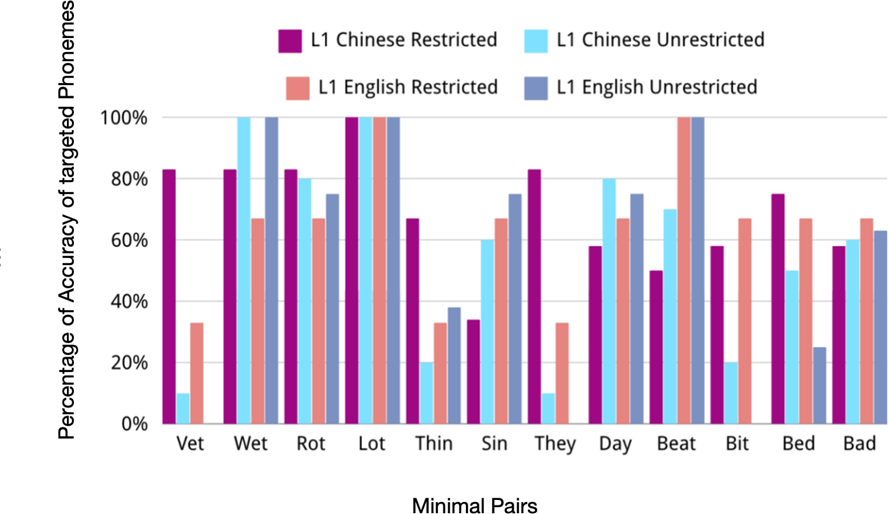

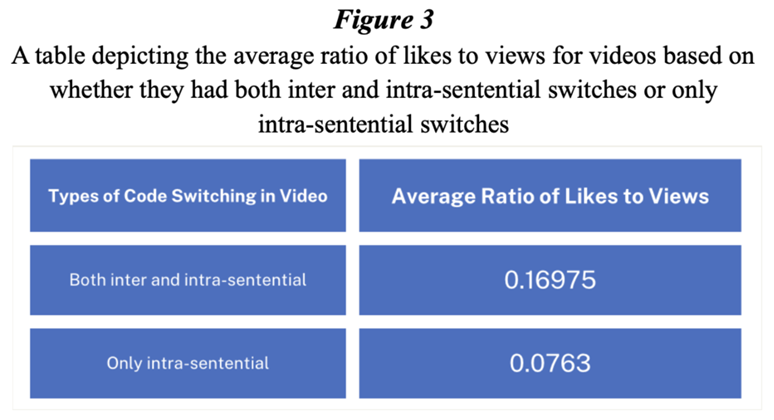

Figure 3: Participants identified the letters read out to them through an audio

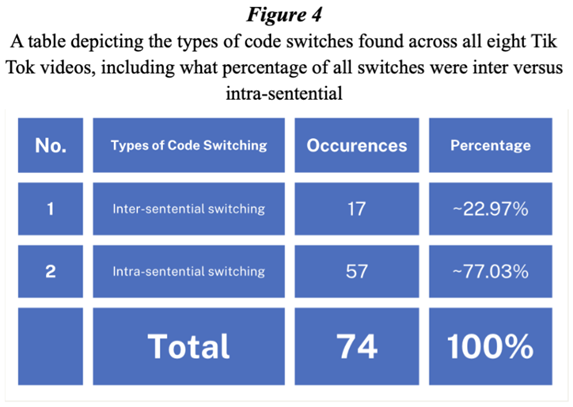

Figure 4: Participants identified the letters read out to them through an audio

Appendix

| Korean Words | Explanation | French Words | Explanation |

| 1. 사람 [ˈsʰa̠(ː)ɾa̠m] | 1. Connecting the phoneme /a/ to the new character ‘아’ | Toute [tut] | In testing the phoneme /u/ and whether learners can connect it to the orthographic element ‘ou’ Different from Spanish ‘u’ |

| 2. 바다 [pa̠da̠] | 2. Dans [dɑn̚] | In testing the phoneme /ɑ/ and whether learners can connect it to the orthographic element ‘a’ No such phoneme in Spanish | |

| 3. 자다 [t͡ɕa̠da̠] | 3. Mais [mɛ] | In testing the phoneme /ɛ/ and whether learners can connect it to the orthographic element ‘ai’ Different from Spanish representation ‘e’ | |

| 4. 모자 [mo̞d͡ʑa̠] | 1. Connecting the phoneme /o/ to a new character ‘오’ | 4. Va [va] | In testing the phoneme /a/ and whether learners can connect it to the orthographic element ‘a’ Control case |

| 5. 도로 [ˈto̞(ː)ɾo̞] | 5. Été [ete] | In testing the phoneme /e/ and whether learners can connect it to the orthographic element ‘e’ Control case | |

| 6. 눈 [nun] | 1. Connecting the phoneme /u/ to a new character ‘우’ | ||

| 7. 구름 [kuɾɯm] |

Discussion and Conclusion

Looking forward, the importance of the information that this study can provide should not be overlooked. Observing potential advantages to knowing one language as an HL and learning a new one can lead to important social implications. Mainly, social stigma about speaking languages can be curbed and lessened. Much like Israel Jesus in the weekly Subtitle podcast episode titled “From linguistic shame to pride” (Spotify Studios 2023), language pride can lead to very big differences in someone’s life. Going from having shame in speaking a language to having the pride to use it to help save someone’s life (like in a medical translation setting for Israel). Give the podcast a listen to hear his story! It provides deep insight into the struggles of speaking a language considered “lesser than” or stereotyped and how knowing that that language is useful in some way can help to overcome stigma and self consciousness. This is the essence of what we hope to investigate.

References

Deng, J. (2022, December 30). The Teaching and Learning of Third Tone Sandhi: L2- and Heritage-Learners of Mandarin Chinese in Canadian University Classes. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching. https://www.clt-international.org/journal/details/info/7ODEu8MzEx/The- Teaching-and-Learning-of-Third-Tone-Sandhi:-L2–and-Heritage-Learners-of-Mandarin-Chinese-in- Canadian-University-Classes

Hopp, H. (2014,January 18). Cross-linguistic influence in the child’s third language acquisition of grammar: Sentence comprehension and production among Turkish-German and German learners of English. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1367006917752523

Lorenz, E. (2018, August 13). Cross-Linguistic Influence in Unbalanced Bilingual Heritage Speakers on Subsequent Language Acquisition: Evidence from Pronominal Object Placement in Ditransitive Clauses. Sage Journals .https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1367006918791296

Mayr, R. (2016, October 16). Inter-generational transmission in a minority language setting: Stop consonant production by Bangladeshi heritage children and adults. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1367006916672590

Montrul, S. (2010, July 3). Dominant language transfer in adult second language learners and heritage speakers. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43103834?sid=primo&seq=7

Westergaard, M. (2016, May 19). Crosslinguistic influence in the acquisition of a third language: The Linguistic Proximity Model. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1367006916648859

Machová, L. (2019, February). The secrets of learning a new language [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/lydia_machova_the_secrets_of_learning_a_new_language?subtitle=en

Spotify Studios. (2023). From linguistic shame to pride [Audio podcast episode]. In Subtitle. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/episode/778VXYt9XxDUUzgKLMzQL6?si=6df3f3ab0f0c454e