Emoji Secrets: Unveiling How Gender and Sexuality Influence Emoji Usage among UCLA Undergraduates

Fangfei Liu, Nuoya Liu, Suzy Xu, Shengliang Jin, Kelly Wu

In the digital communication era, emojis have become a new form of vibrant visual language that transcends words into icons that convey emotions and ideas. Imagine this: It’s a typical Friday evening, and a group of friends at UCLA are planning their weekend via text messages. One friend, excited about the upcoming party, sends a string of emojis – a bottle of champagne , a partying face , and a confetti ball . Another friend, more reserved, responds with just a simple thumbs up. As these messages fly back and forth, a fascinating question arises: what do these tiny digital symbols say about us? Can these tiny digital symbols reveal deeper insights into our identities and social interactions? In fact, emojis not only distribute information but also reveal more profound aspects of an individual’s identity. This research focuses on the intersection between gender and sexuality and how these identity factors play a role in influencing emoji usage among UCLA undergraduate students. By launching a mixed-methods approach, the study combines statistical analysis and qualitative content examination to indicate trends and patterns in emoji selection. The findings highlight significant differences in emoji use across genders and sexual orientations and provide insights into the various ways that individual identities shape their digital expressions.

Introduction

👋👋 Hey! The rise of digital communication has introduced emojis as a new form of language, expressing emotions, ideas, and more. Emojis hold symbolic significance and cultural connotations, making them a rich subject for linguistic analysis and in-text communication studies. Here’s the link to a TED talk titled “Emoji: The Language of the Future” by Tracey Pickett, which discusses the cultural significance and evolution of emojis.

When investigating in-text communication dynamics, especially in the context of gender and sexuality, Deborah Tannen’s difference model of communication (2007) lays a theoretical foundation, suggesting that men and women use distinct styles of speech: men typically adopt a report style focused on conveying information, whereas women use a rapport style aimed at building relationships with high involvement.

Despite growing research, there’s a gap in understanding how gender and sexuality intersect with emoji usage. Our study aims to investigate how these identity categories influence emoji use among UCLA undergraduates. By employing mixed methods, including statistical analysis and qualitative content analysis, we will identify trends and nuances in emoji selection among different gender and sexual identity groups. This research will contribute to the broader understanding of how diverse identity factors shape digital communication.

Background

Emojis are small digital icons that help with facilitating emotions and expressions during online interactions today. The icons are prevalent among the younger generation, such as college students, who are active users of online communication platforms. Prior research has indicated emojis’ socio-linguistic significance, reflecting the user’s identity, emotional state, and cultural background. Gender and sexuality are two critical factors in examining the dynamics of emoji use, and our research aims to investigate the impact these two factors have on college students’ use of emojis in online conversations.

Gender differences in emoji use have been a subject of interest in existing literature, as highlighted in Herring et al.’s research. They found distinct patterns of emoji use among different gender groups. For instance, women tend to use emojis that express solidarity and support, while men are inclined towards emojis related to sarcasm and teasing (Herring et al. 2018). The influence of sexual orientation on emoji use habits among LGBTQ+ individuals has also been explored by other scholars. Gray, for instance, has noted that emojis serve as in-group codes that aid in identity expression (Gray 2023). Our research will focus on the impact of gender and sexuality on emoji usage among diverse UCLA undergraduate students and discover the characteristics of emoji habits among different groups shaped by their backgrounds.

Methods

In this study, we used a mixed-methods approach (i.e., including statistical analysis and qualitative content analysis) in this study to identify trends, preferences, and nuances in emoji selection among different gender and sexual identity groups.

This research incorporates a convenience sampling, whereby our group members send online Google Forms to a total of 50 UCLA students to collect data on their use of emojis. And, our online survey included demographic questions about race, school year, gender, and sexual orientation. It also included the collection of screenshots of emojis that they used frequently. Finally, after completing the data collection, we analyzed all the data by using R studio and

Excel software to assess the statistical correlation between gender identity and the frequency of using certain emojis.

Results and Analysis

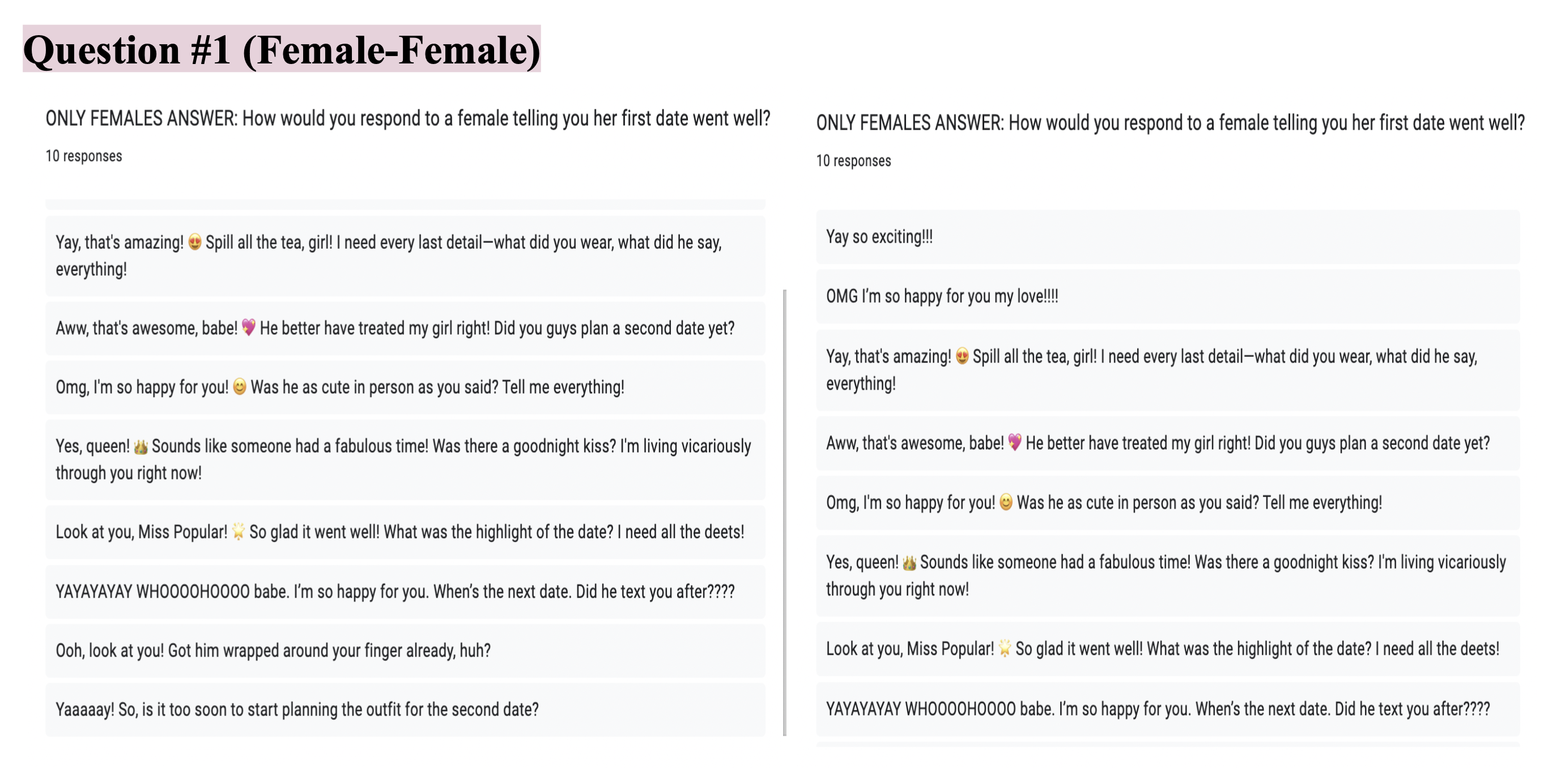

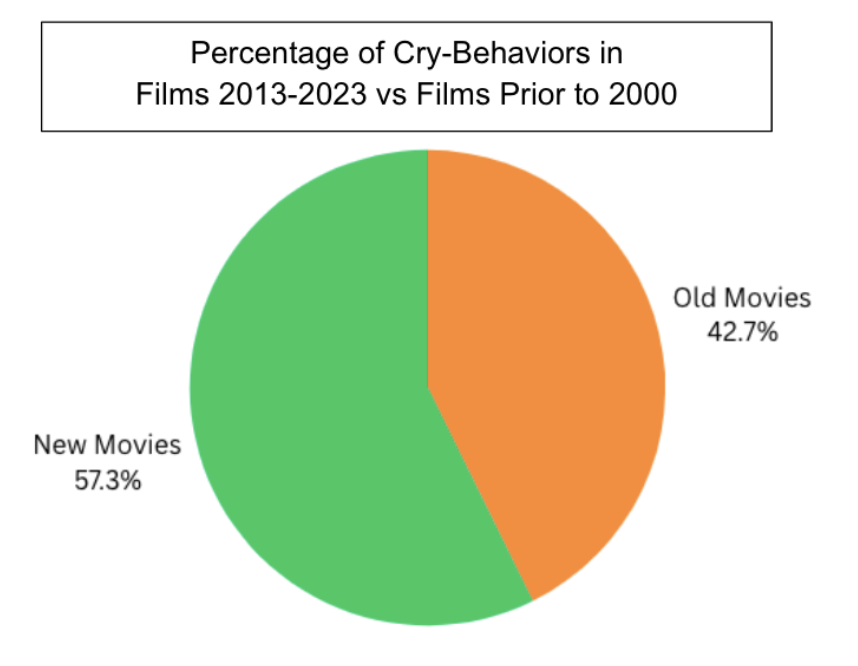

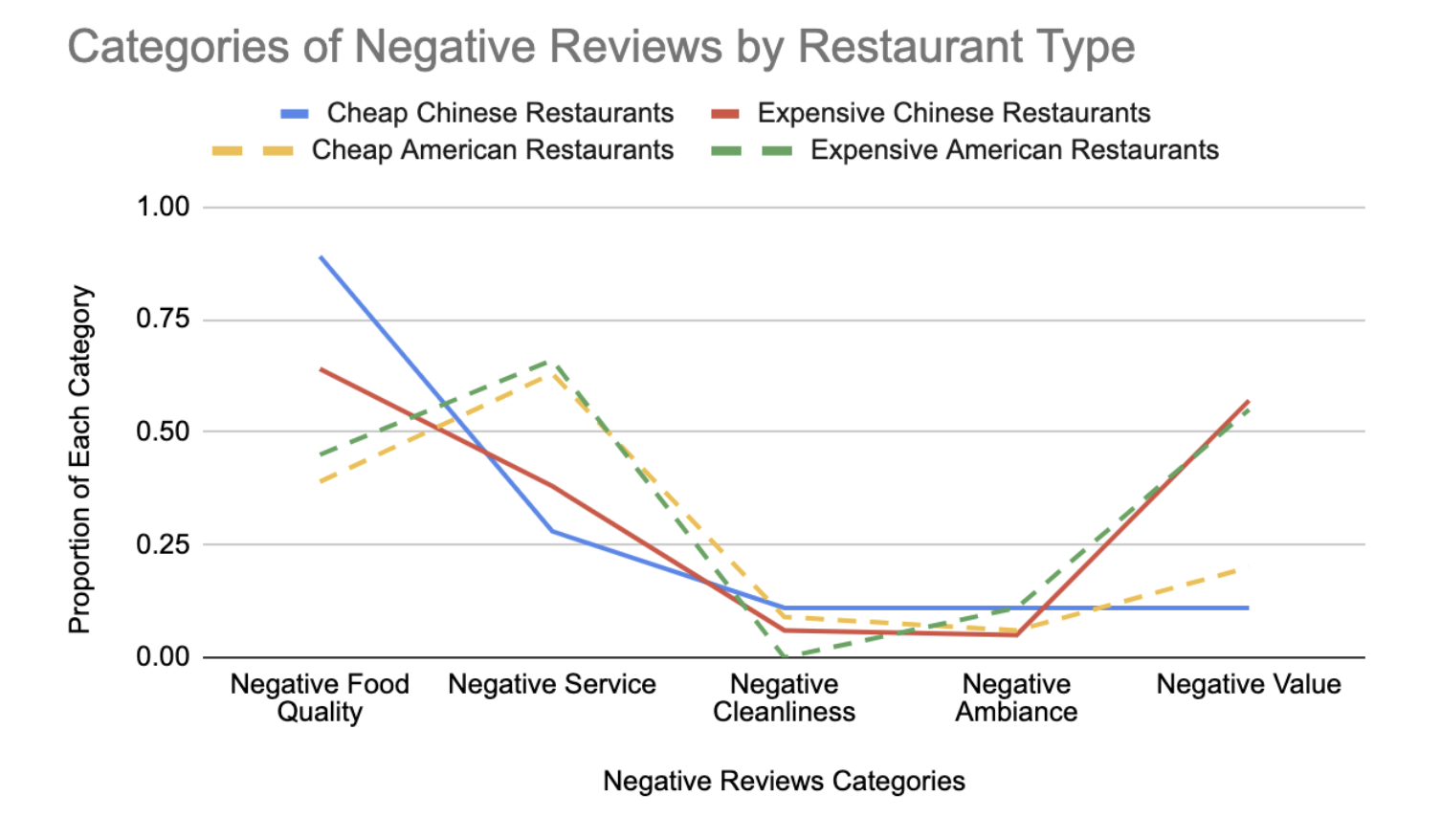

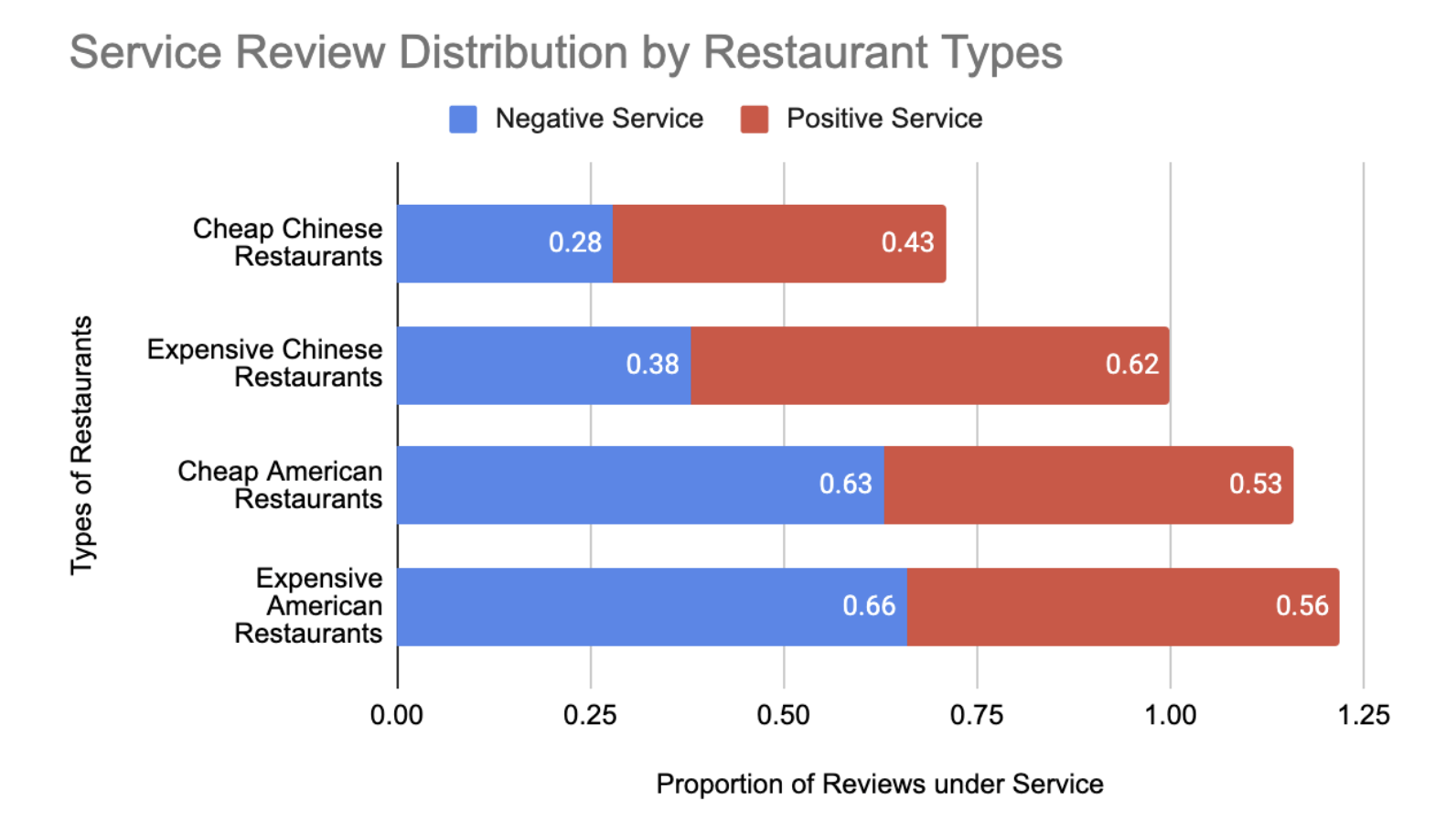

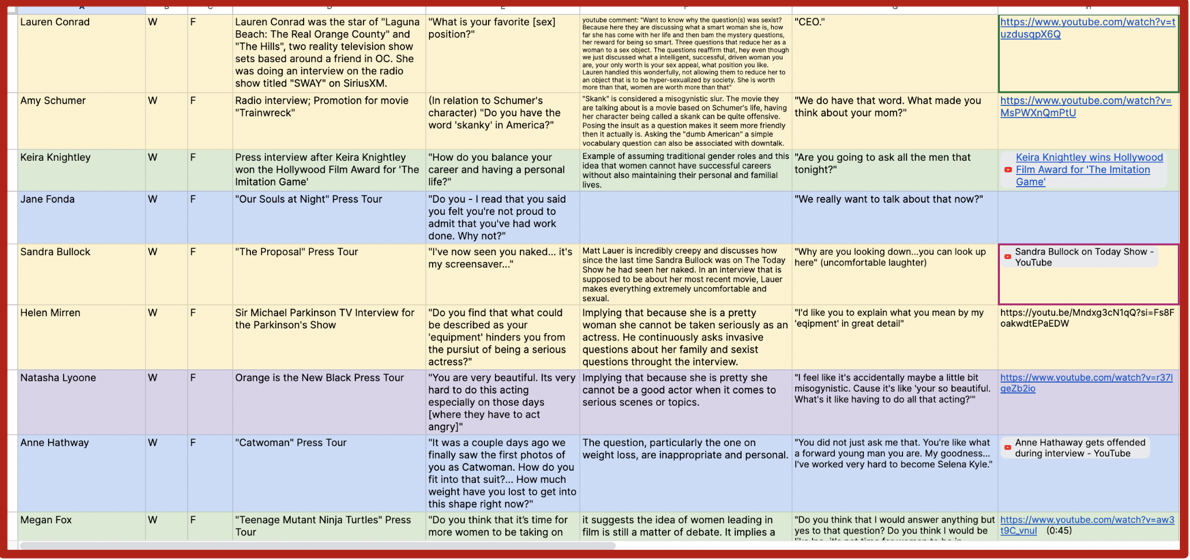

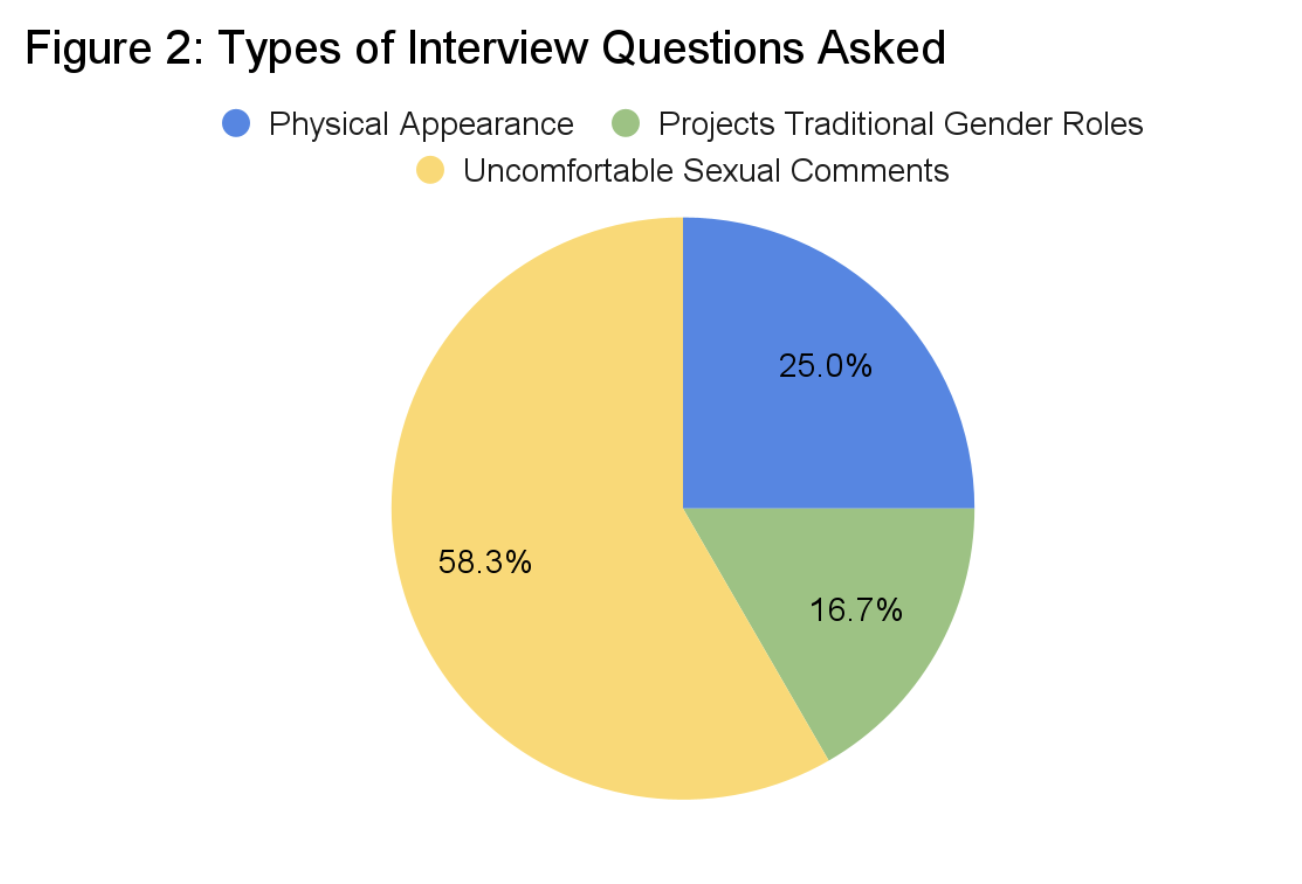

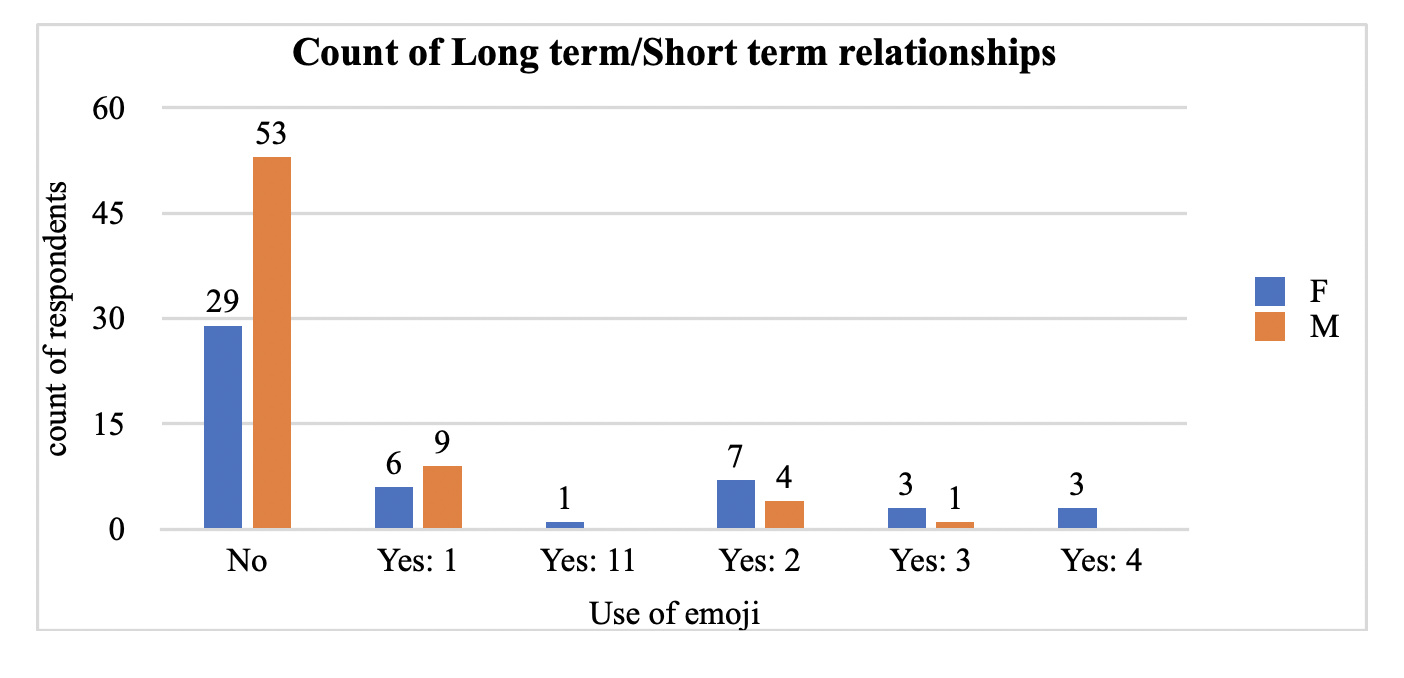

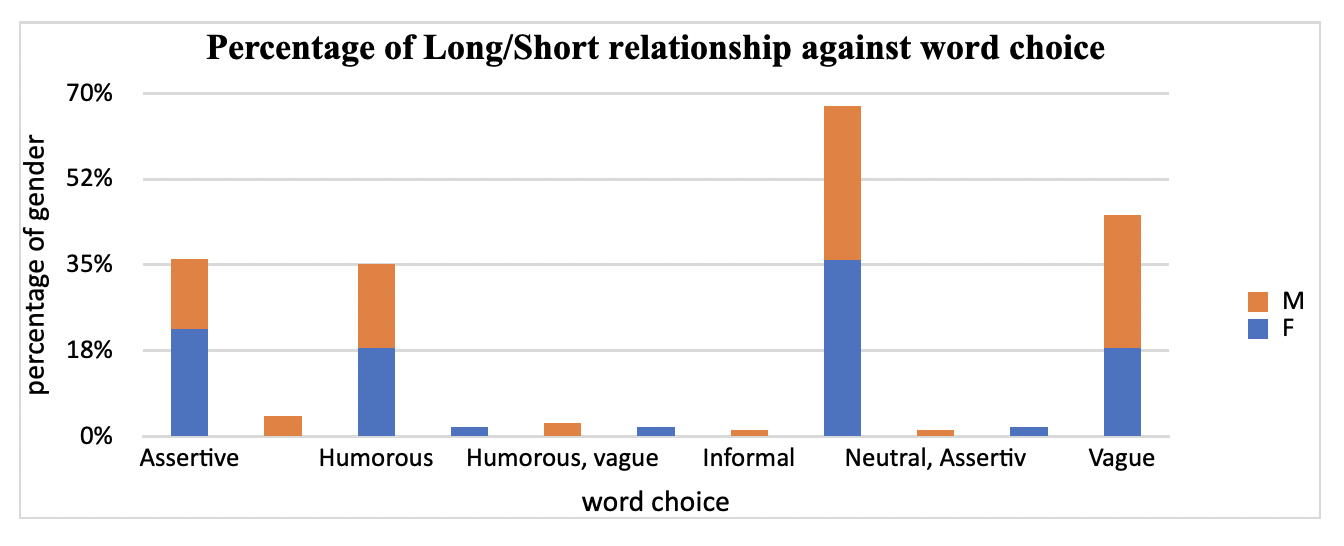

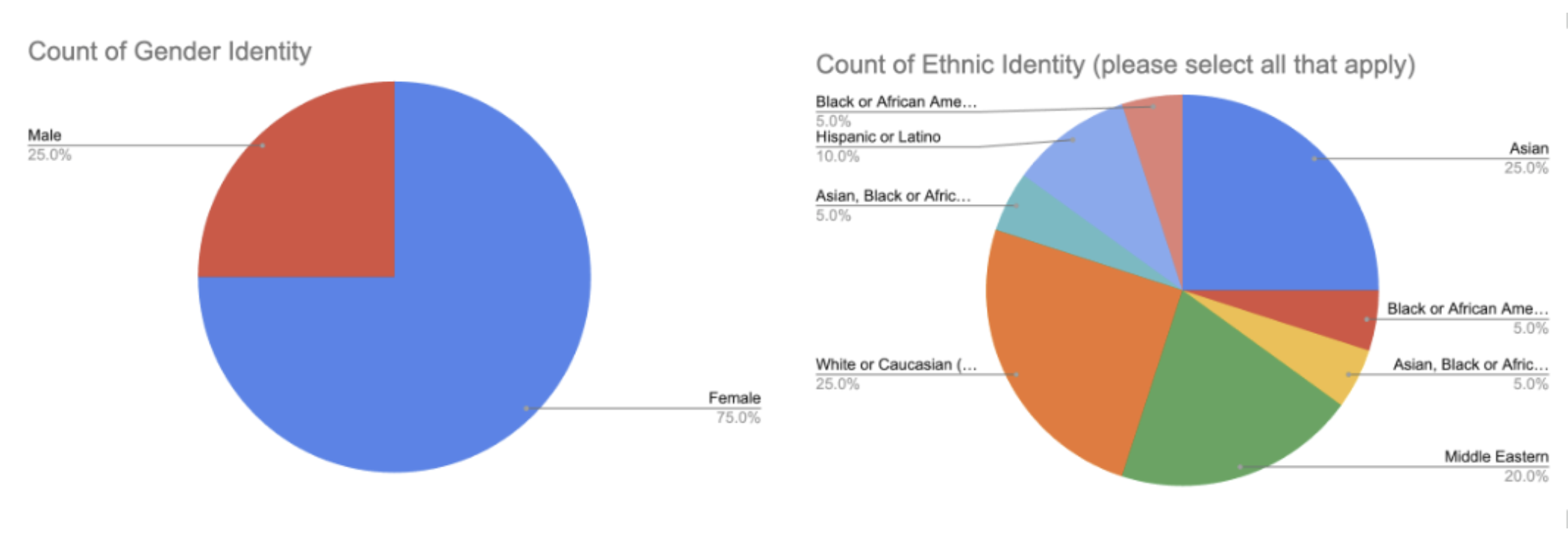

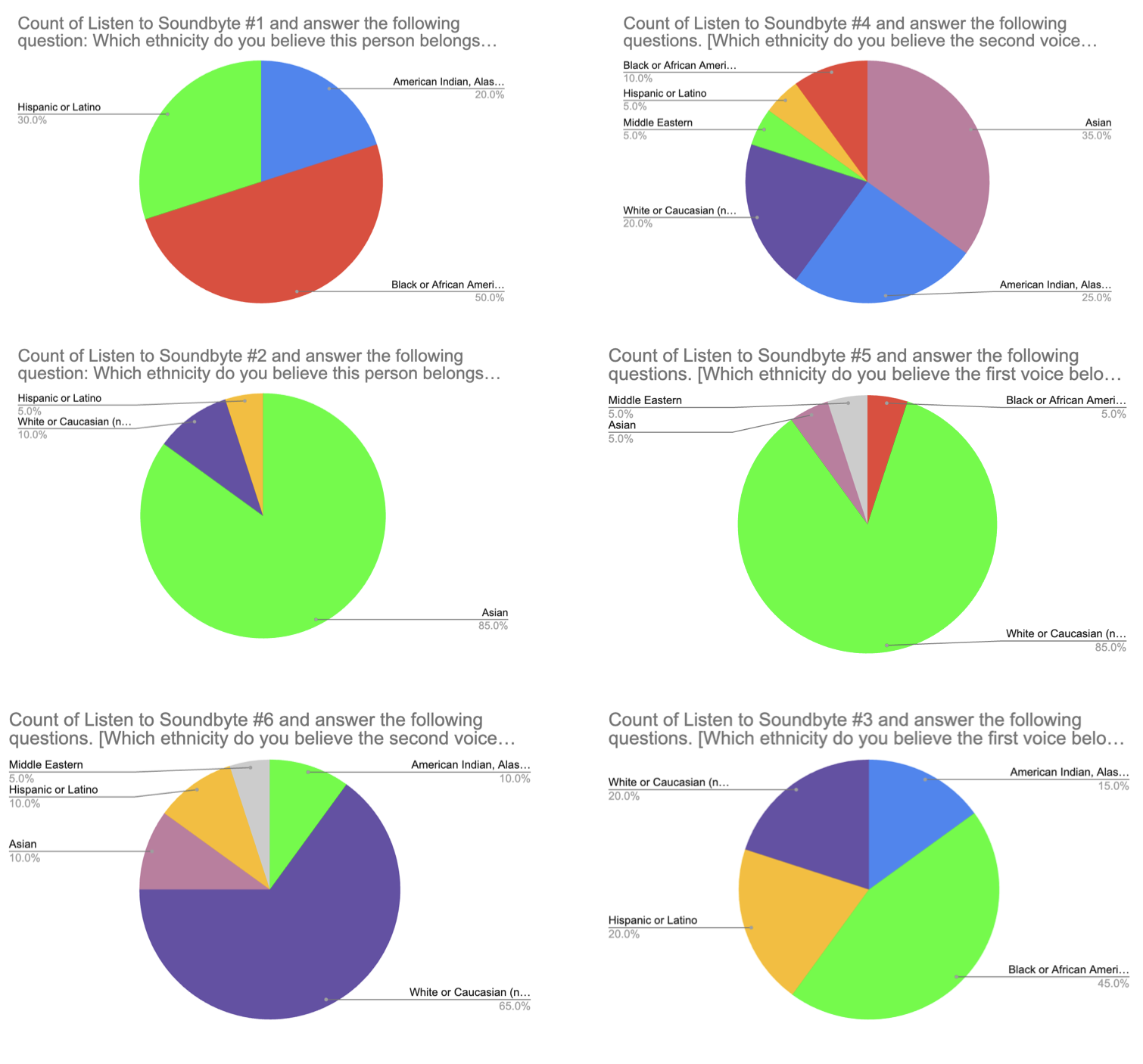

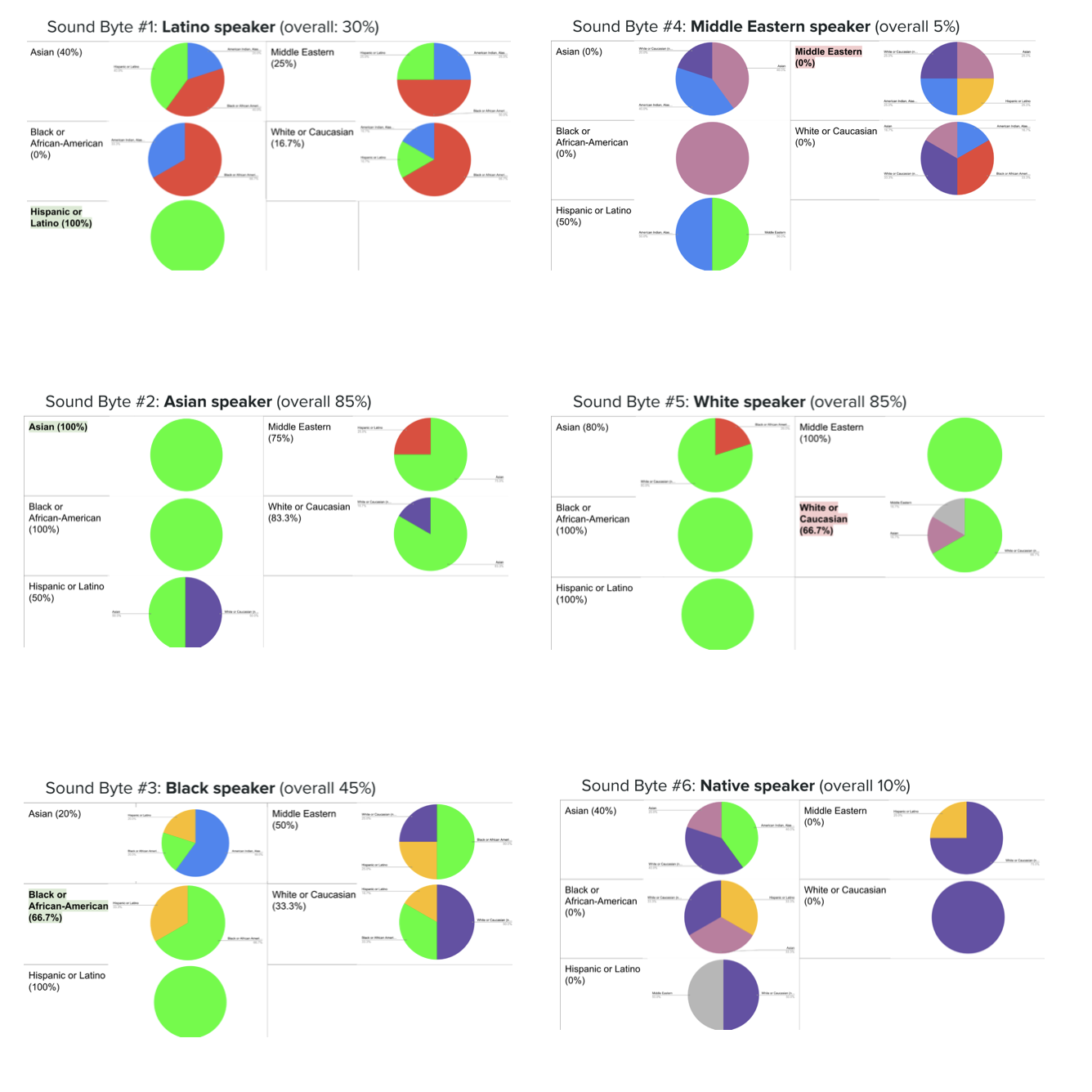

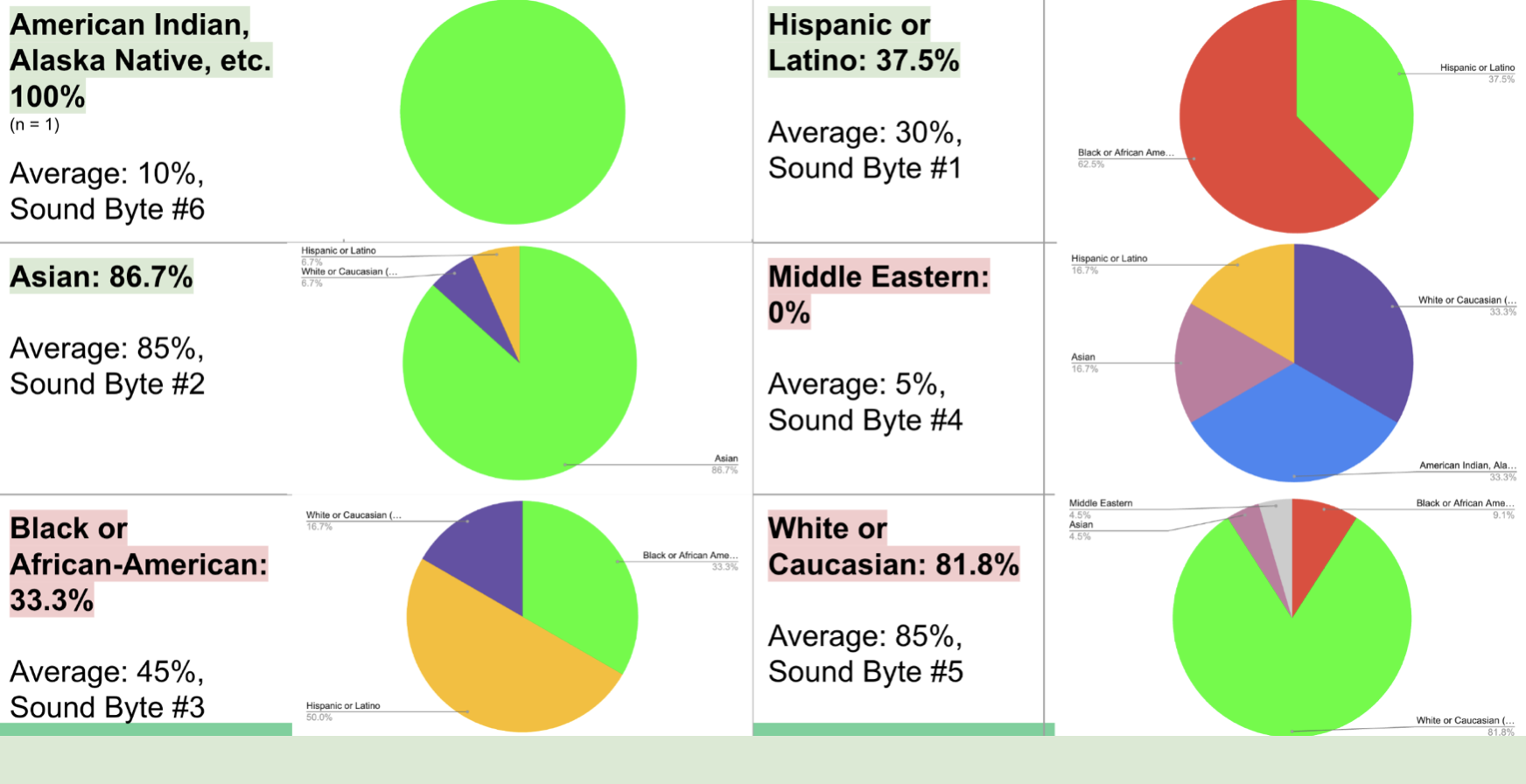

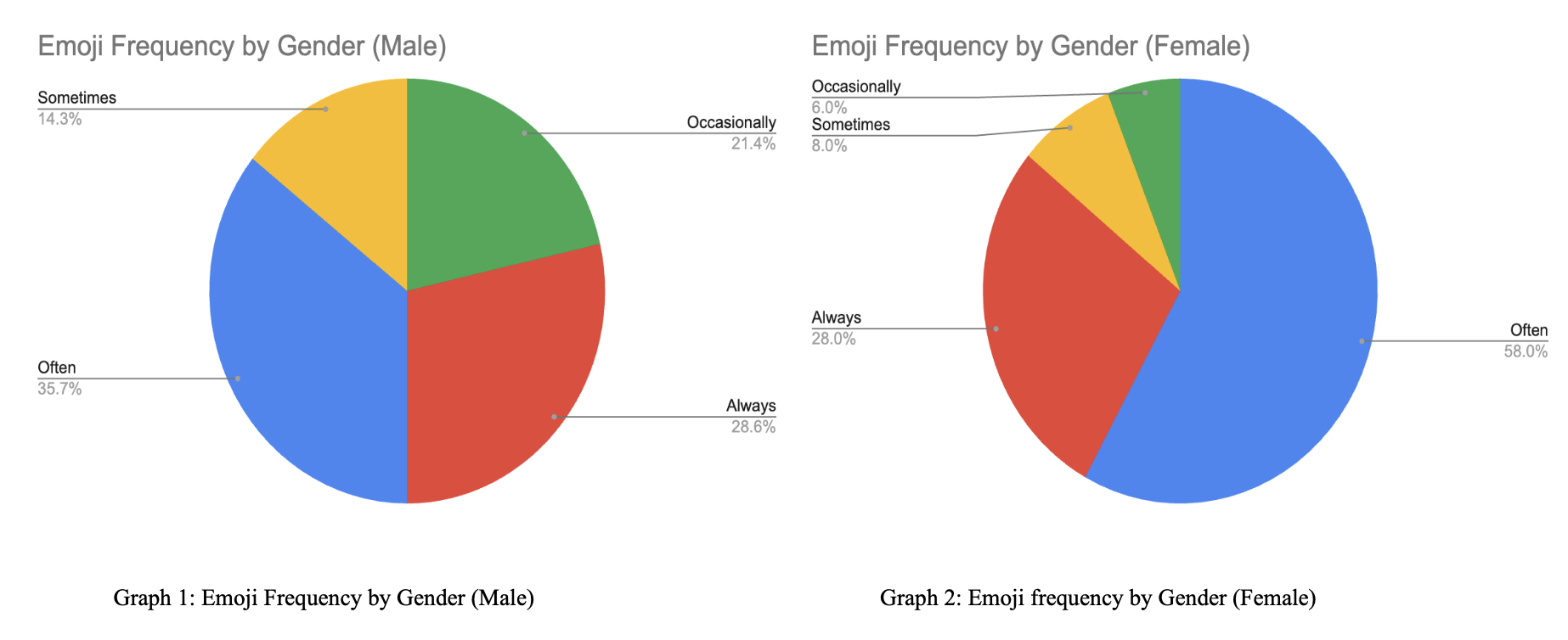

After collecting responses from all 50 UCLA undergraduates, our research presents a comprehensive analysis of the data collected on emoji usage among undergraduate students at UCLA by including both quantitative data and tabular analysis as well as qualitative content analysis. First, the data were processed to create a dataset with the frequency and types of emojis used by different groups. The pie graphs shown below illustrate the emoji frequency based on students’ gender while indicating that female students use emojis more frequently than male students do. For instance, the number of female students who selected the option “often” is 23% higher than that of male students; there are more than 1⁄5 of the male students select the option “occasionally” to show their dispreferred attitude of utilizing emojis when texting with others.

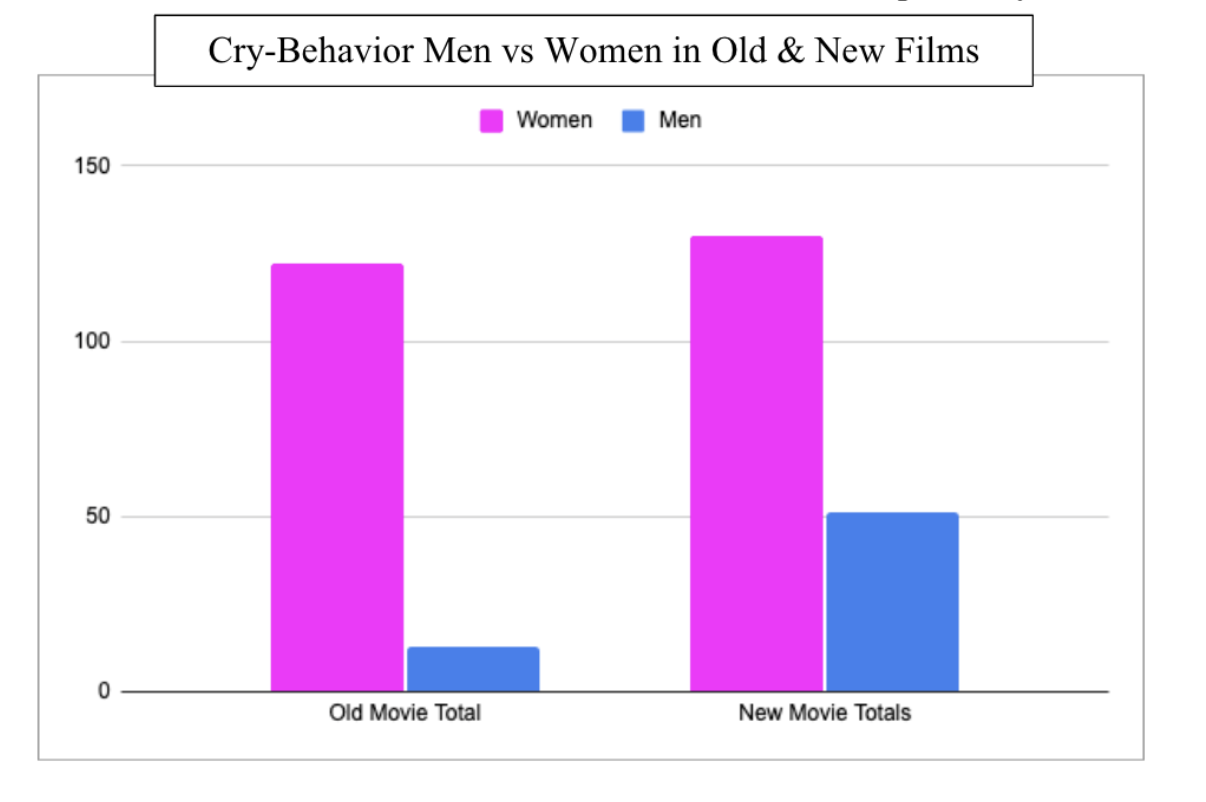

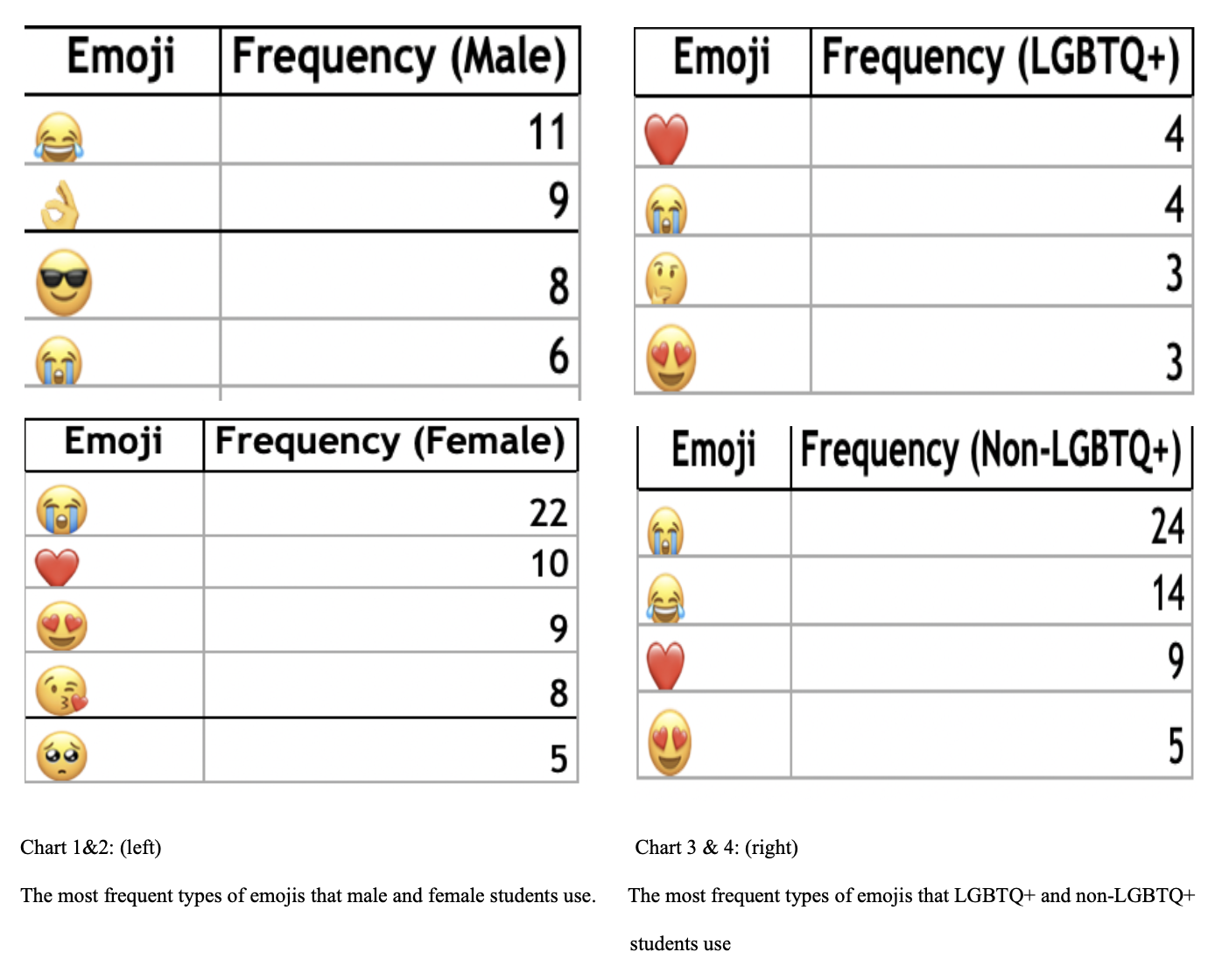

We also created some charts showing the top 5 most frequently used emojis based on students’ gender and sexual orientation. On the left side, charts 1 & 2 show the most frequent types of emojis that male and female students use during online communication. From here, we could see that the average number of different emojis used by females was significantly higher, indicating a broader expressive range. More specifically, emojis such as 😭, ❤️, 😍, and 🥺 were predominantly used by female students, emphasizing a wider variety and a relatively higher frequency of emoji usage. On the contrary, male students demonstrated a more limited and functional use of emojis. Emojis included 😂, 😎, 👌 and reflected their preference for simpler, less emotionally varied communication.

On the right side, charts 3 & 4 show the emoji frequency based on students’ sexual orientation as LGBTQ+ students exhibited distinctive patterns in emoji usage. While emojis such as ❤️ and 😍 were used by LGBTQ+ members to convey nuanced social interactions, some emojis such as 🤔️, which might not be as prevalent among heterosexual students, were used for unique identity expressions.

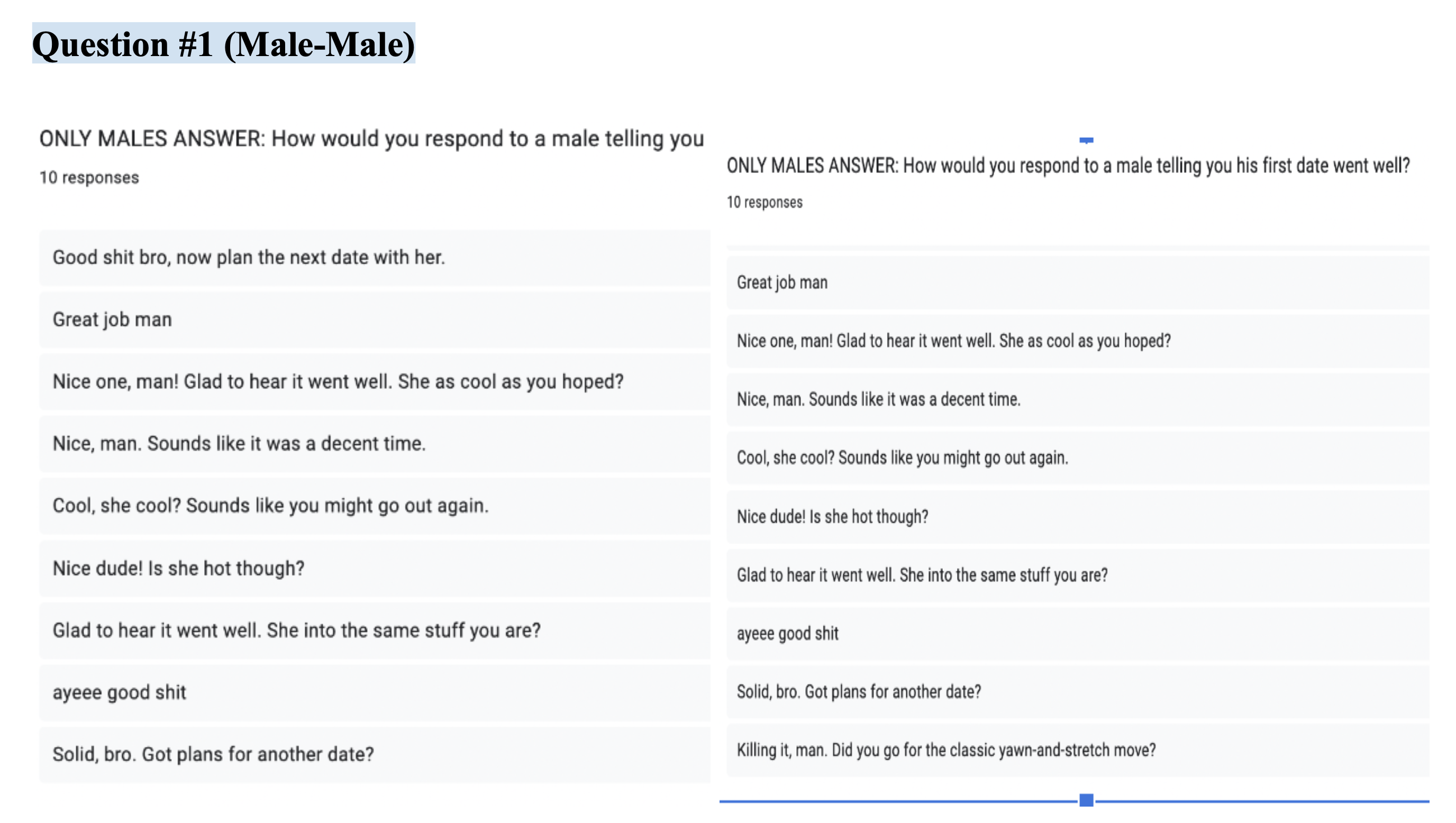

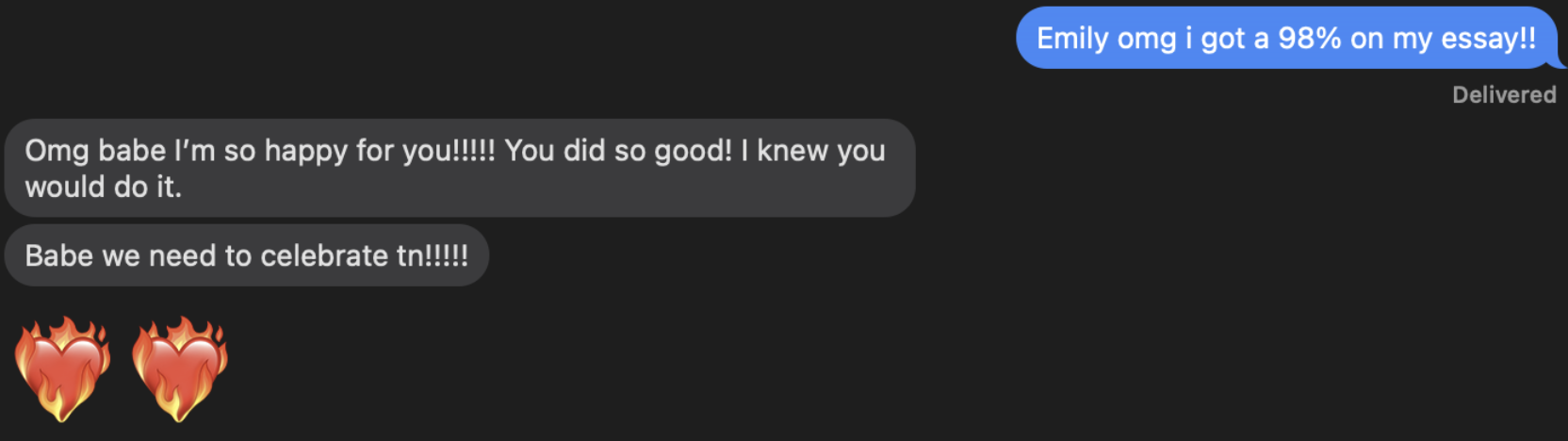

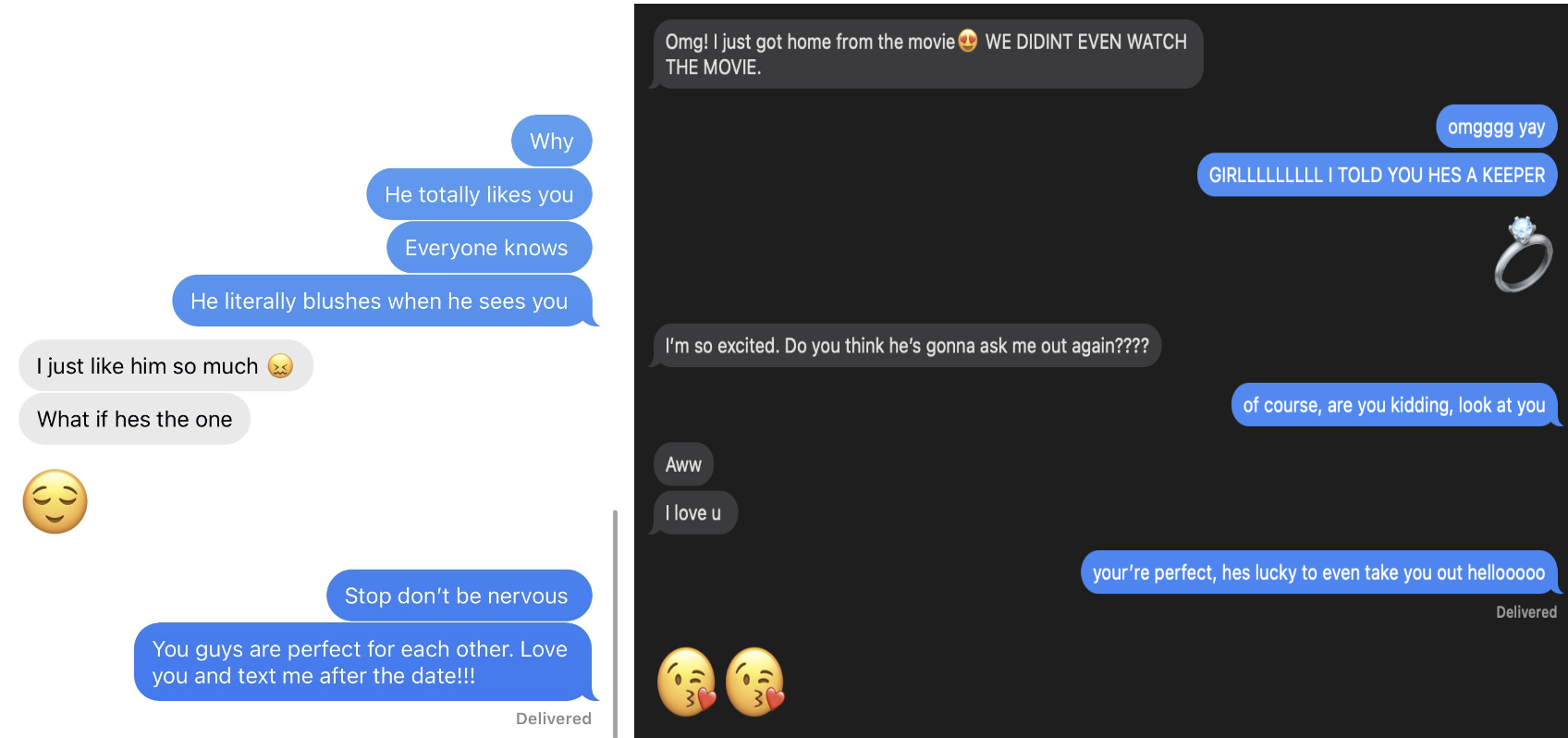

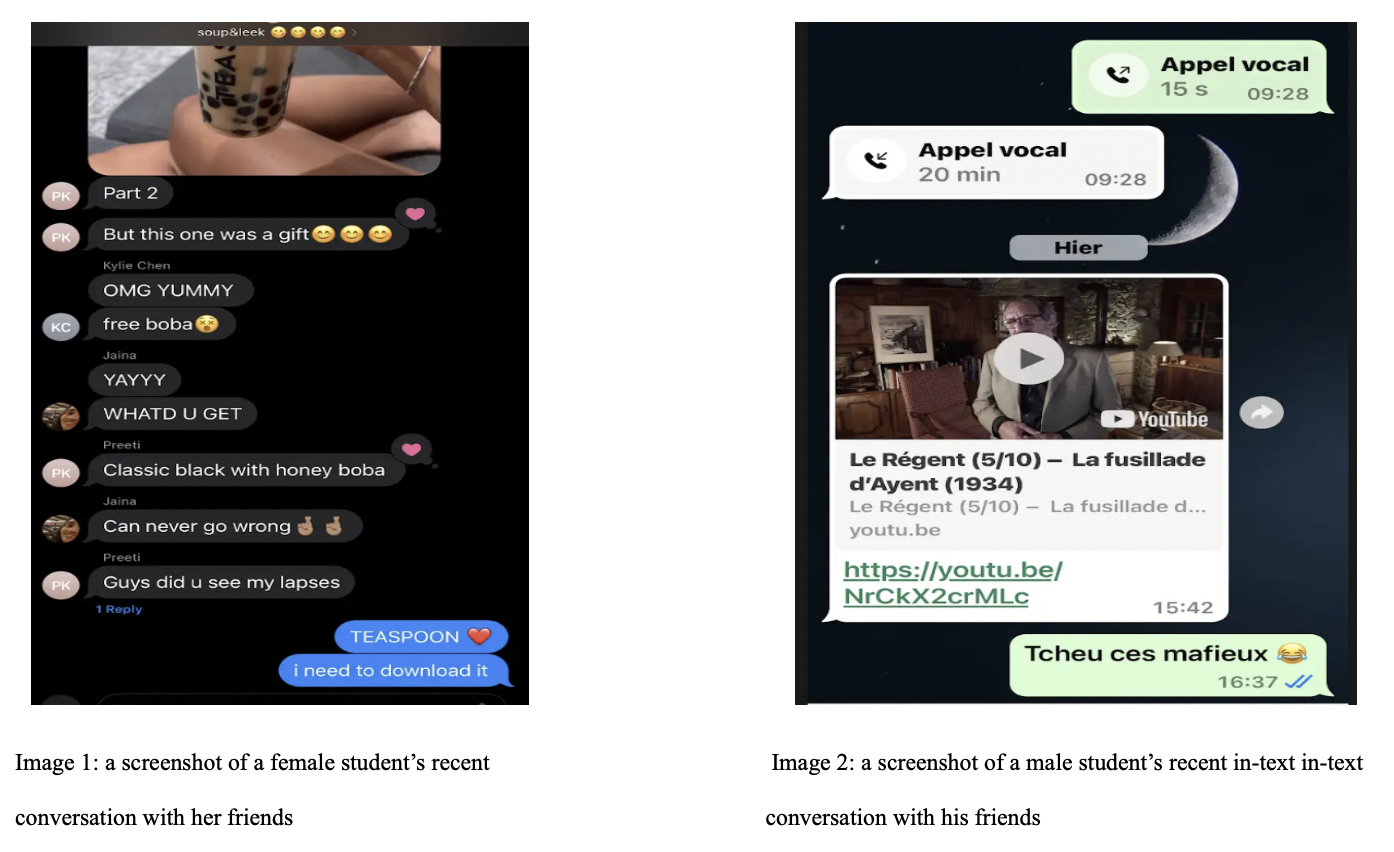

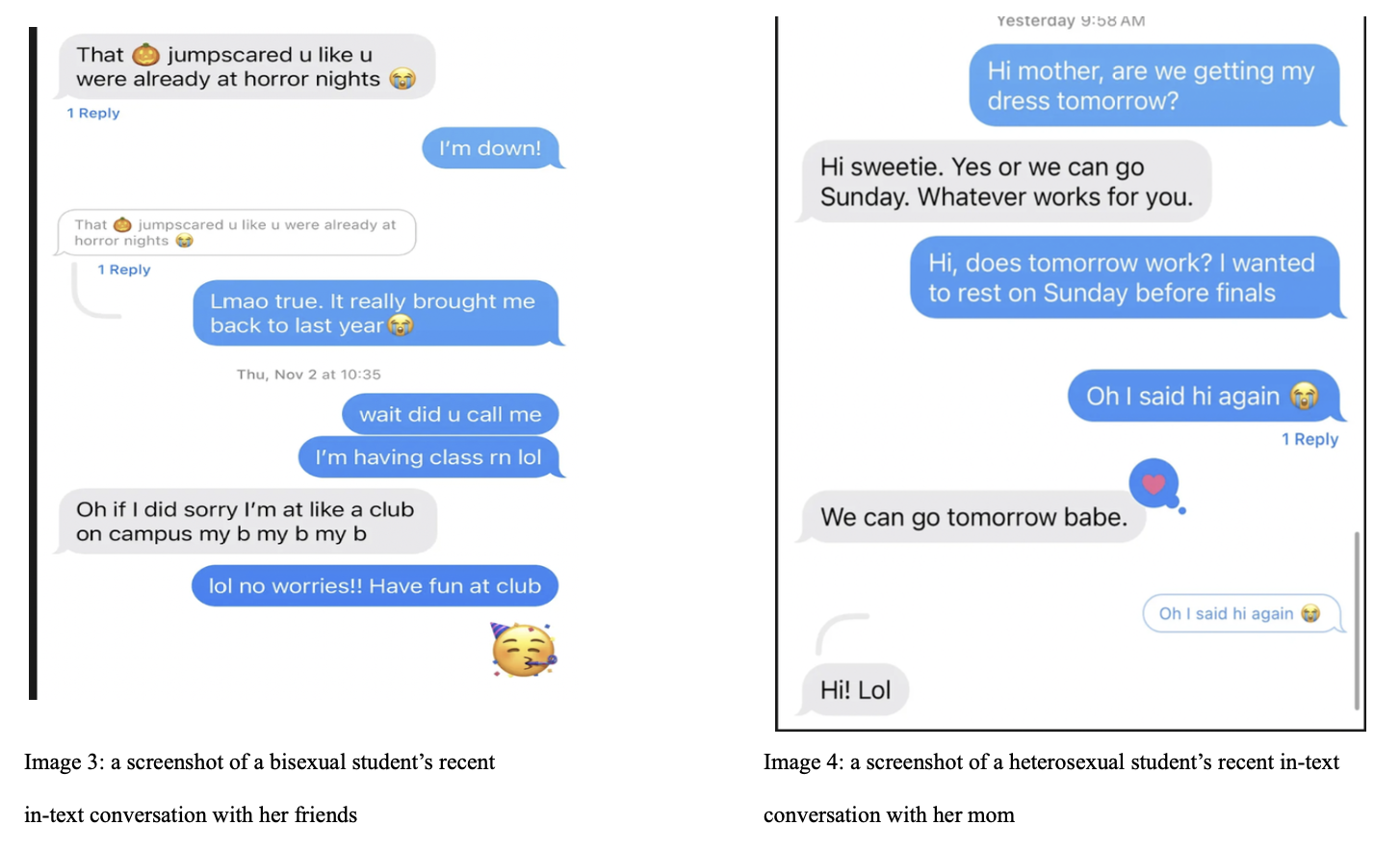

Besides doing quantitative analysis, we also focus on content analysis which examines the context and meanings behind emoji usage for each gender and sexuality group through collecting screenshots of their recent in-text conversation where they used emoji. From the gender perspective, female students tend to use emojis to express a wide range of emotions, from joy and love to sadness and empathy. For instance, emojis like 😭 and 🥺 often appear in conversations involving apologies or sharing emotional experiences, indicating a high level of emotional expressiveness; The use of ❤️ and 😍 highlights the importance of emotional support and connectivity in their interactions.

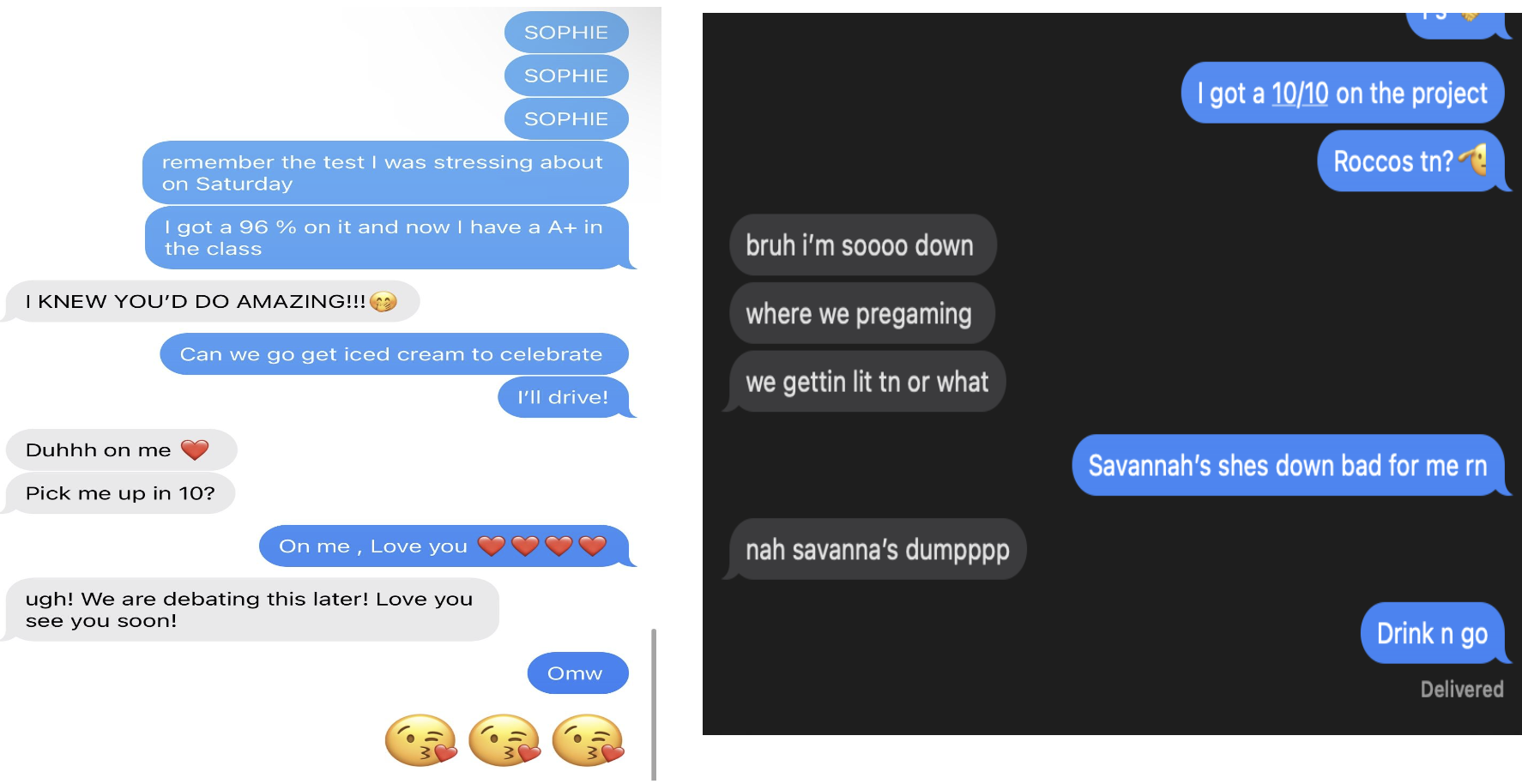

From Image 1, a female student claimed that she used a heart next to a “teaspoon” because she loves their boba. This illustrates her desire of providing emotional feedback to maintain her social bonds with her friends. Nevertheless, male students tend to use a narrower range of emojis to add humor and casualness into their interaction. Emojis such as 😂 and 😎 are commonly used in light-hearted conversations, indicating a preference for maintaining a relaxed and friendly tone. From Image 2, a male student was reacting to a funny video and this indicates his tendency to be friendly and approachable while implicitly showing his preference of having a simple and straightforward conversation.

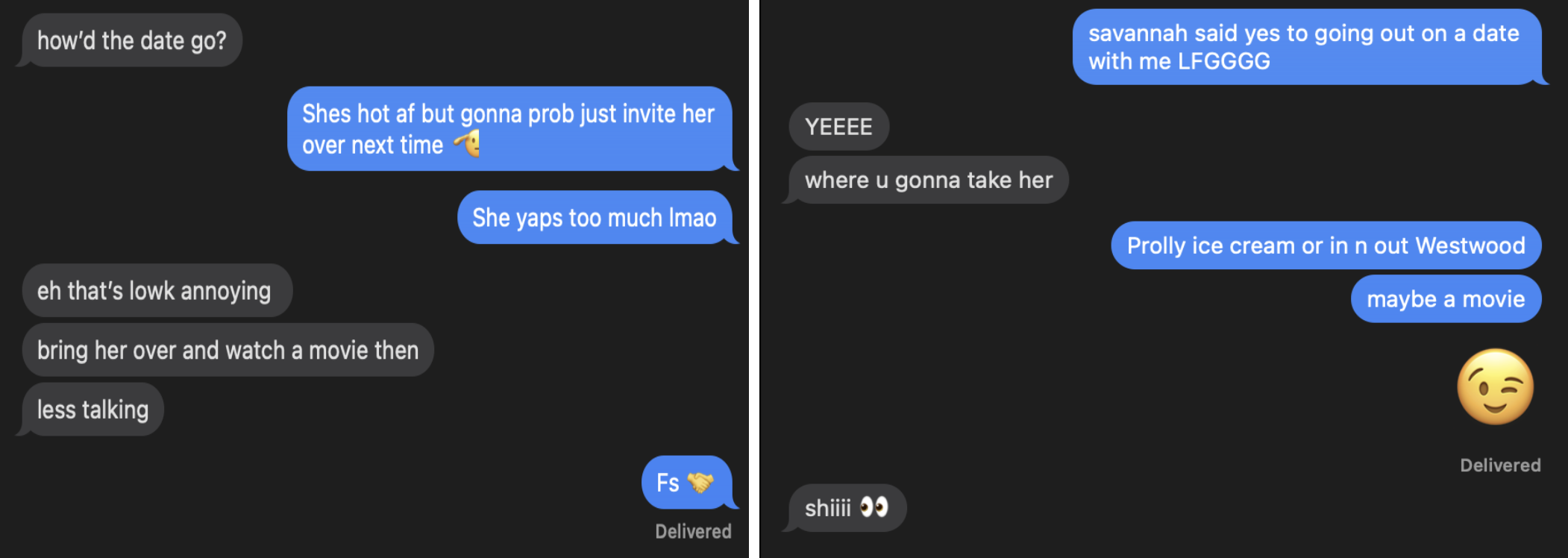

From the sexuality perspective, members of the LGBTQ+ community use emojis to convey complex social interactions and support. Some emojis which might not be as prevalent among heterosexual students, appear to express empathy and encouragement while highlighting positivity and uniqueness in conversations.

From Image 3, a bisexual female student said that she was wishing her male friend to have a fun night at the club. The emojis such 🥳 and 🎃 reflects the LGBTQ+ users’ different approach to expressing encouragement and connectivity. Conversely, non-LGBTQ+ students tend to utilize a standard set of emojis that are widely understood and conventional in the community. Emojis such as 👍 and 👌 were commonly used to suggest a preference for simplicity and directness during conversation. In Image 4, a heterosexual female student was texting her mom and asking her when she would like to come with her to get a dress for graduation. The appearance of the emoji 😭 reflects a preference for widely recognized emotional expressions while indicating her demand to facilitate clear and efficient communication.

Discussion

The results of our study highlight notable variations in the use of emojis among UCLA undergraduates according to gender and sexual orientation, which has important societal ramifications for interpersonal interactions. In contrast to males, who often use emojis less frequently and instead concentrate on humor or information sharing, women are more likely to utilize a wide variety of emojis to communicate emotions and foster connections. Emojis are a tool that LGBTQ+ people use to communicate who they are and to challenge social standards. By accommodating a variety of communication styles, recognizing these distinctive patterns can promote teamwork in educational and professional contexts, improve relationships with others by encouraging better understanding and empathy, and support the acceptance and normalization of LGBT identities. By adopting these realizations, we may build a more compassionate and diverse society where digital communication tools are tailored to meet the diverse needs of all users.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support our hypothesis that there are significant differences in the frequency and types of emojis used between male and female undergraduate students at UCLA. Female students tend to use emojis more frequently and choose from a wider variety, including emoticons like 🥺, 😭, ❤️, and 😍, indicating high emotional expressiveness. On the other hand, male students prefer a narrower range of emojis such as 😂 and 😎, reflecting humor and casualness in their communication style.

Moreover, our findings suggest that members of the LGBTQ+ community, such as gay and lesbian individuals, use emojis in distinct ways to express identity and convey nuanced social interactions not as prevalent among heterosexual students. LGBTQ+ individuals often use emojis like ✨, 🌟, and 🥳 highlighting positivity, uniqueness, and emotional depth in their digital expressions. In contrast, non-LGBTQ individuals tend to use simpler emojis like 👌 and 👍 and 😭, indicating a preference for directness and simplicity in their communication. These findings have important implications for understanding how gender and sexuality influence emoji usage in digital communication. They shed light on the complexities of digital interaction and social media communication, informing future studies in this area.

References

Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Mu, Z., & Yang, M. (2019). A Systematic Review of Emoji: Current Research and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221

Gray, M. (2023). Emojis and the Expression of Queer Identity: A Sentiment Analysis Approach. Master’s Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Herring, S. C., & Dainas, A. R. (2018). Receiver interpretations of emoji functions: A gender perspective. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Emoji Understanding and Applications in Social Media. Stanford, CA.

Jones, L. L., Wurm, L. H., Norville, G. A., & Mullins, K. L. (2020). Sex differences in emoji use, familiarity, and valence. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 106305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106305

Pickett, T. (Speaker). (2017, May 17). Emoji: The Language of the Future [Video]. TEDxGreenville. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dzlek8nMrc8

Tannen, D. (2007). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation (1st Harper pbk. ed., pp. 74-96). New York, NY: Harper.

Wolf, A. (2004). Emotional expression online: Gender differences in emoticon use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(5). Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/10949310050191809