In-Person vs. Digital Communication Styles Among Classmates

Megu Kondo, Devina Harminto, Yixing Wang, Yinlin Xie, Batool Al Yousif

In the rapidly evolving landscape of communication, the distinction between in-person and digital communication has become a focal point of linguistic and sociocultural studies. This project delves into the nuanced differences in language use, expression, and understanding across these two modes of communication. The purpose of this study is to investigate how individuals adapt language styles, tones, and dialects between in-person and digital communication. Additionally, our study aims to explore these preferences specifically among classmates, shedding light on the nuances of their communication choices. By examining various linguistic features such as informality, use of emojis, turn-taking, and the adaptation to the absence of non-verbal cues in digital platforms, this study illuminates how digital communication often necessitates a shift from traditional language norms observed in face-to-face interactions. We designed a survey using Google Forms for accessibility and ease of distribution and collected data from 30 college students (18-22 years old) who engage in both in-person and digital communication.

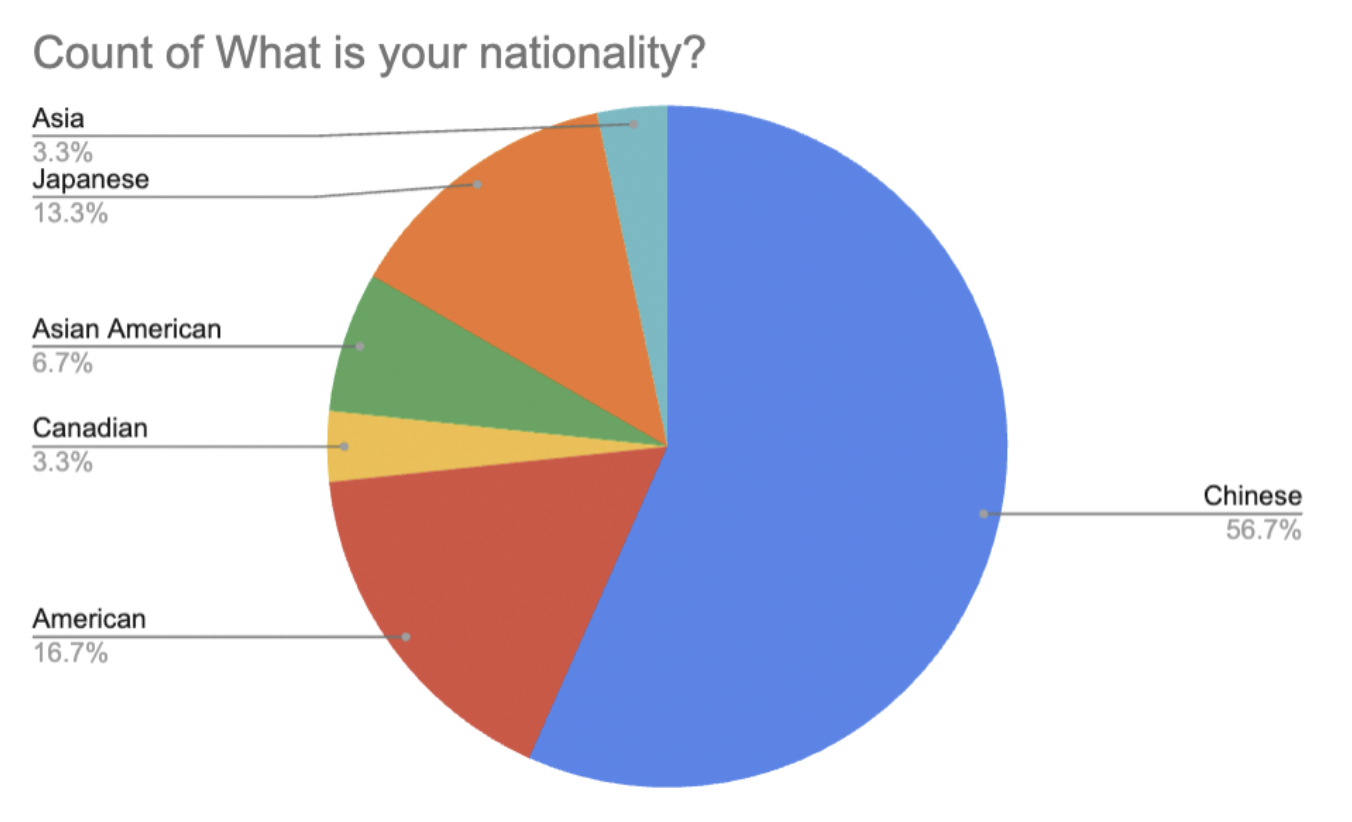

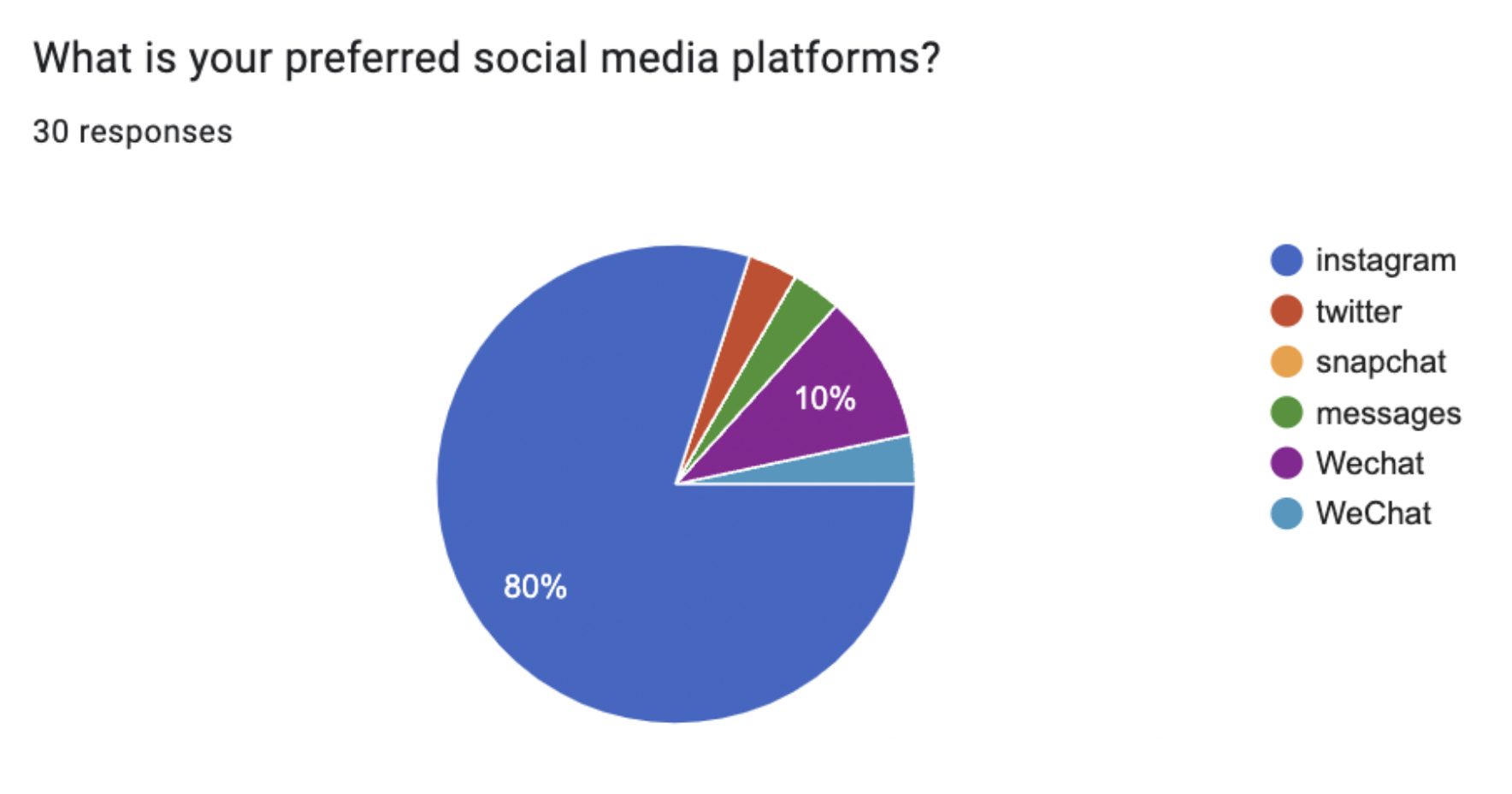

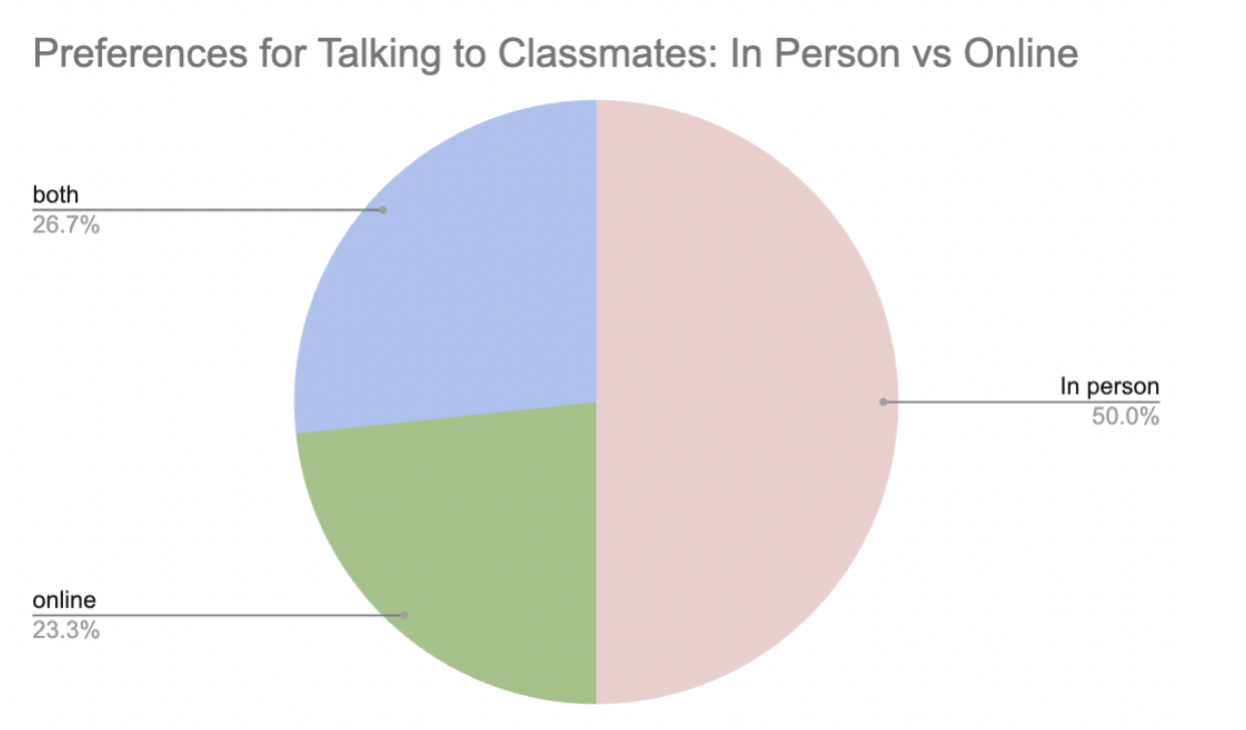

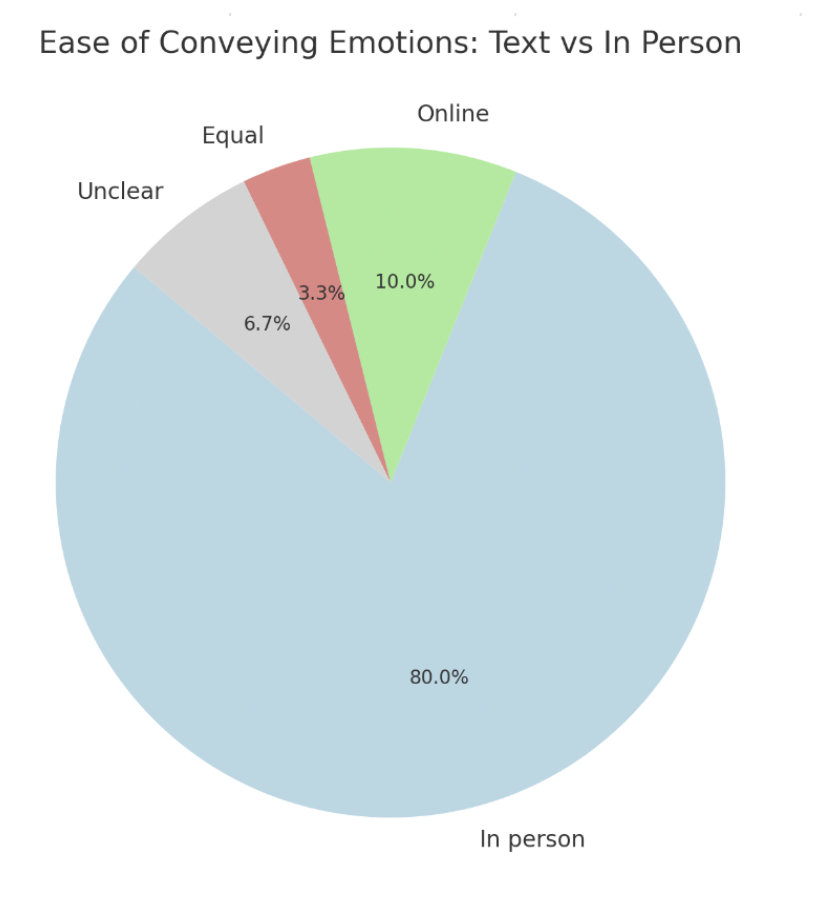

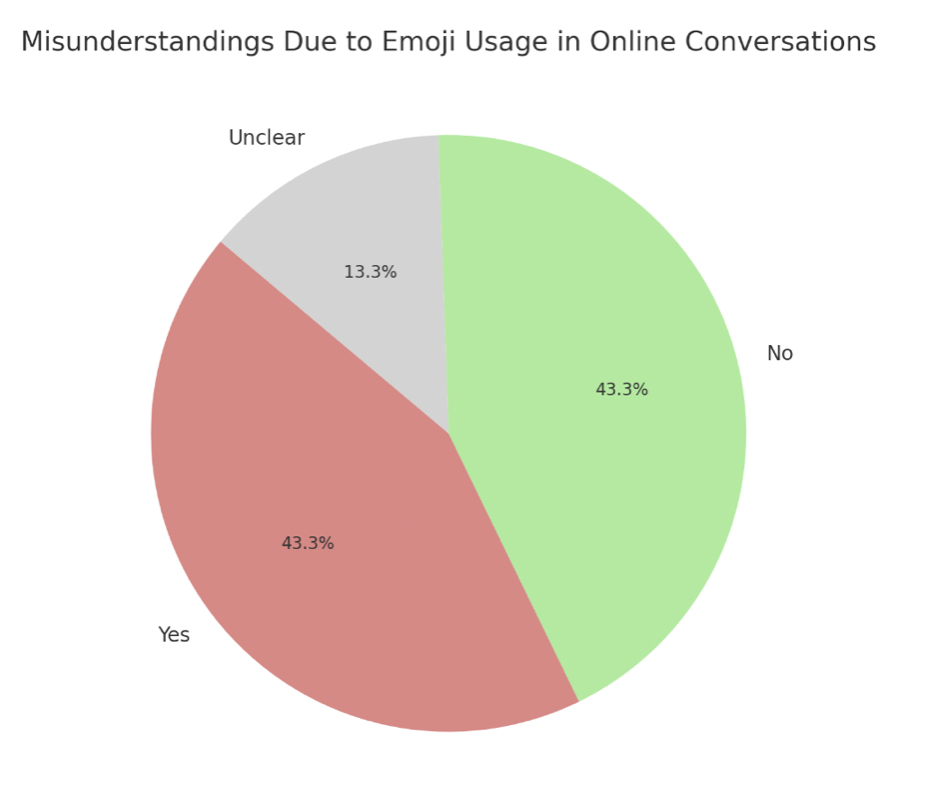

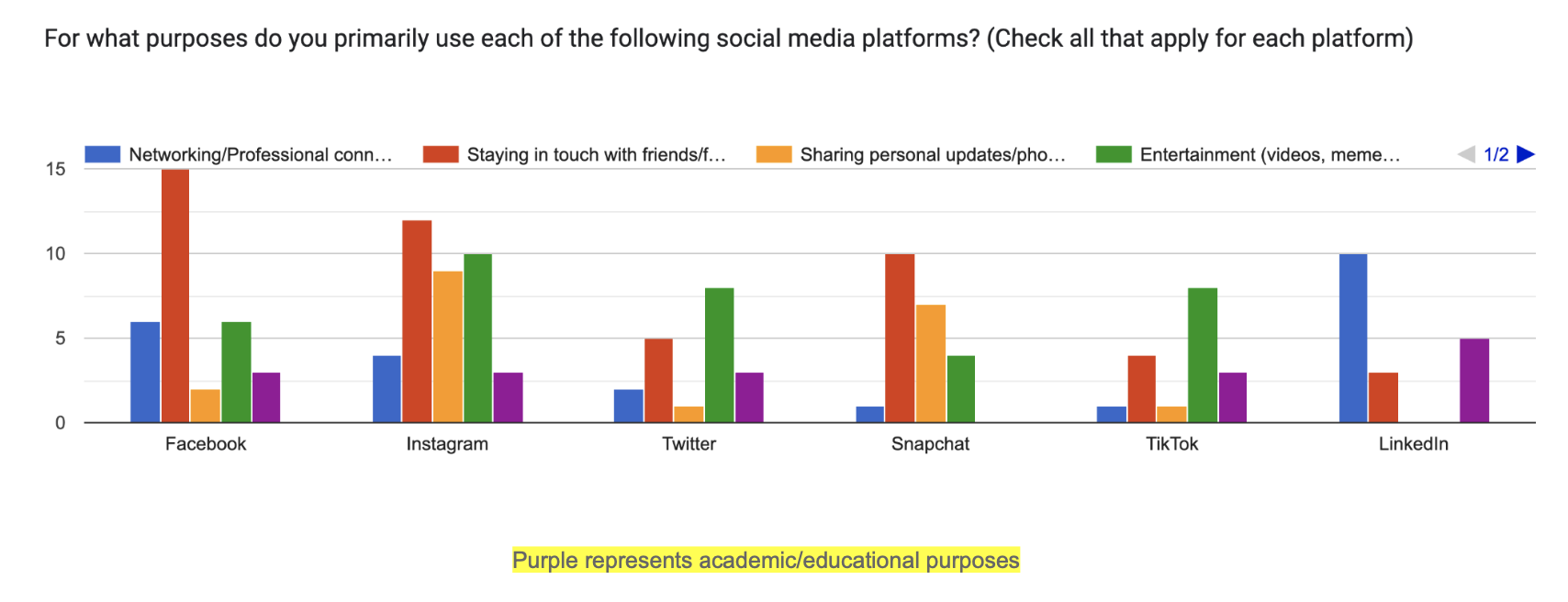

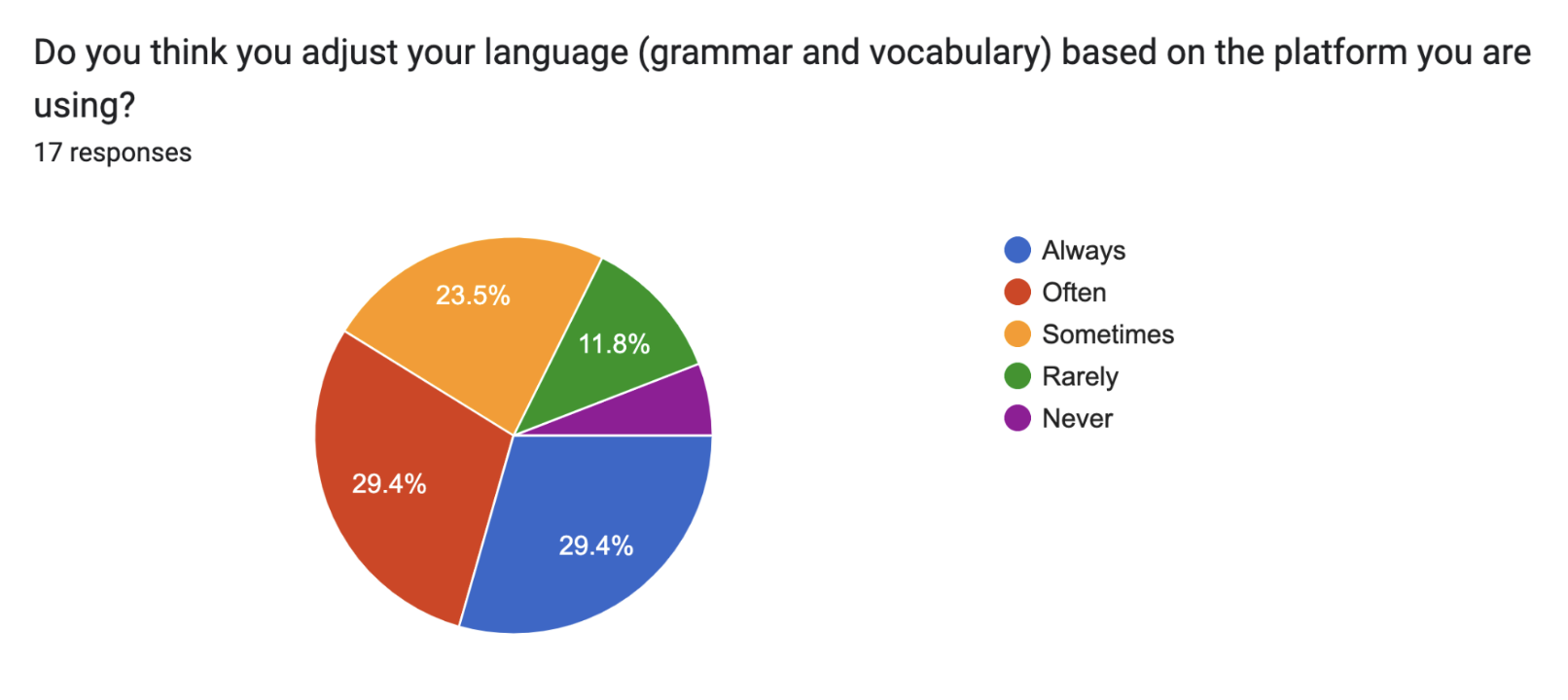

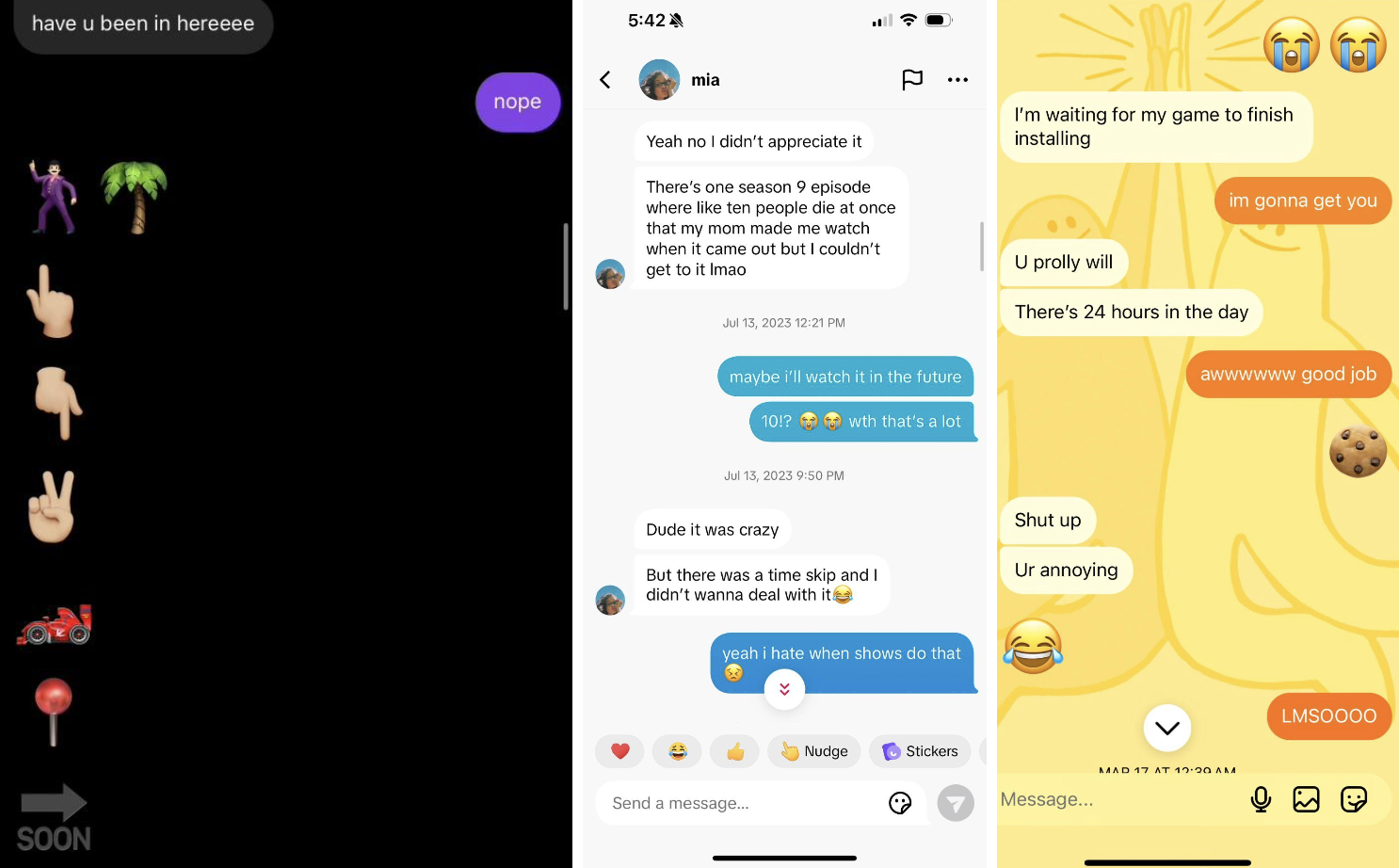

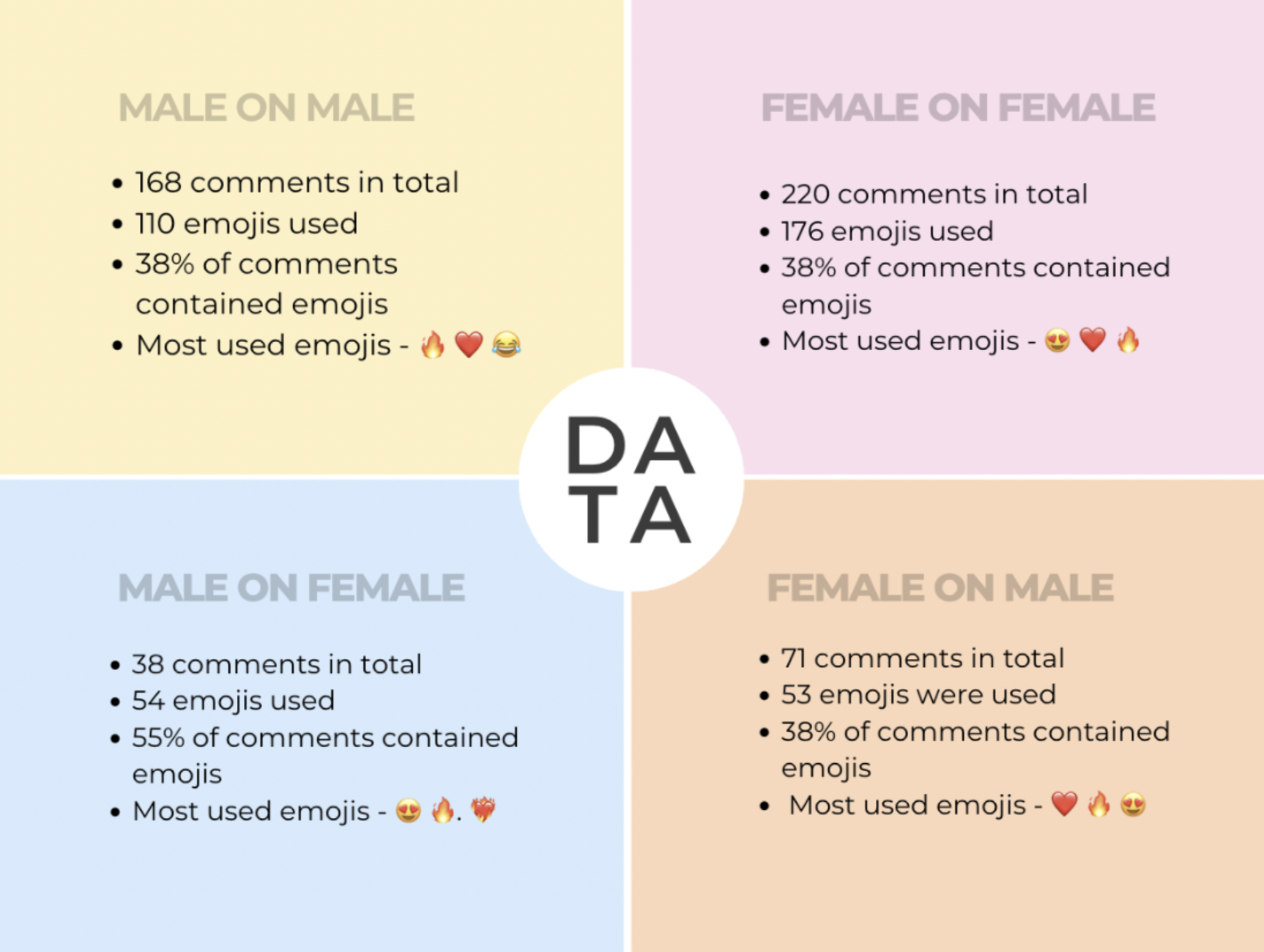

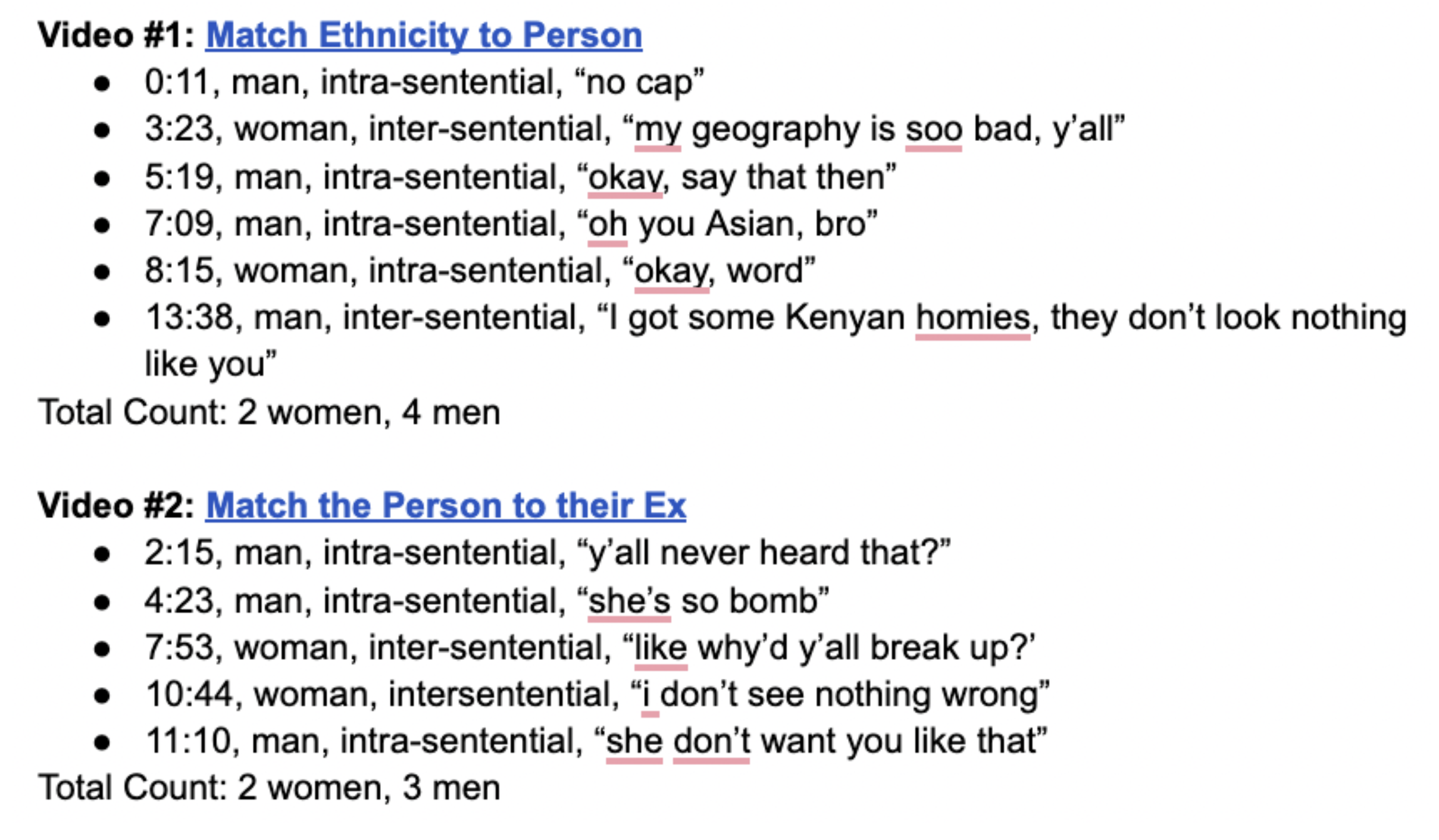

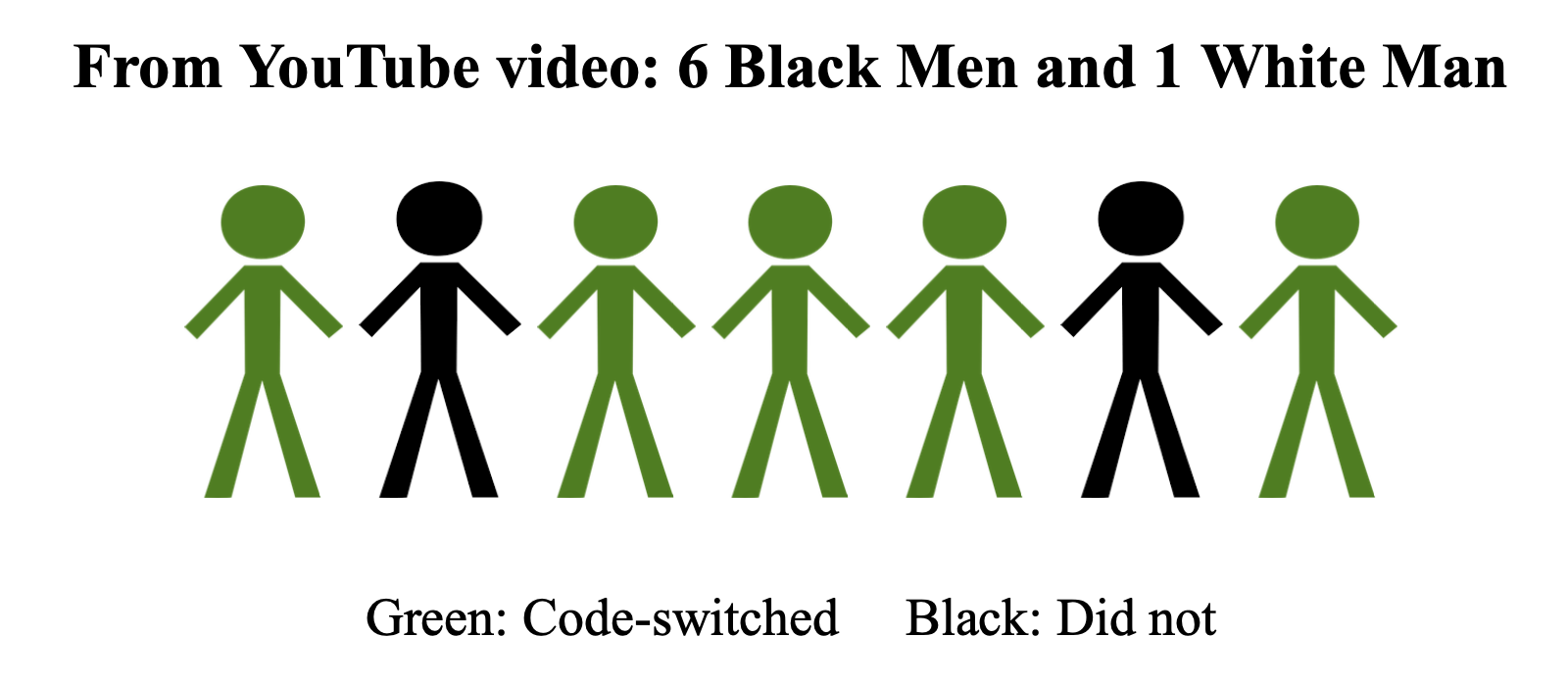

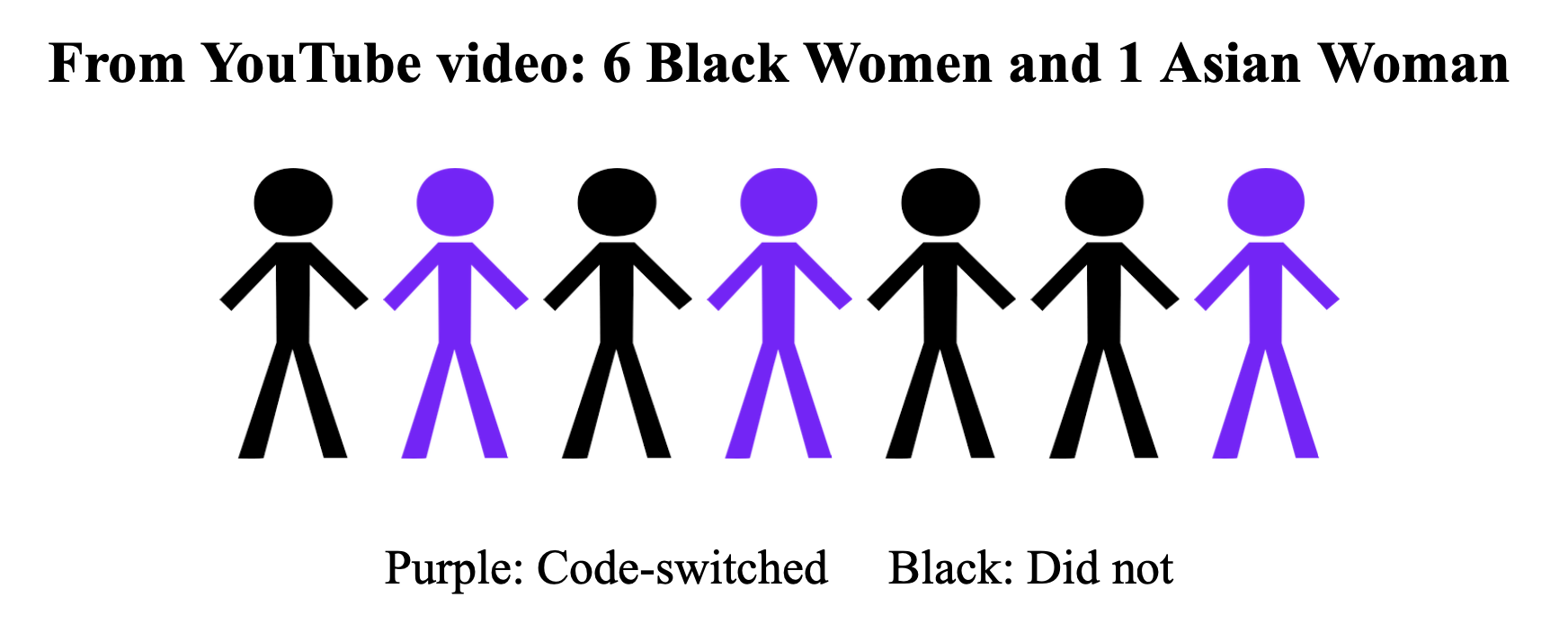

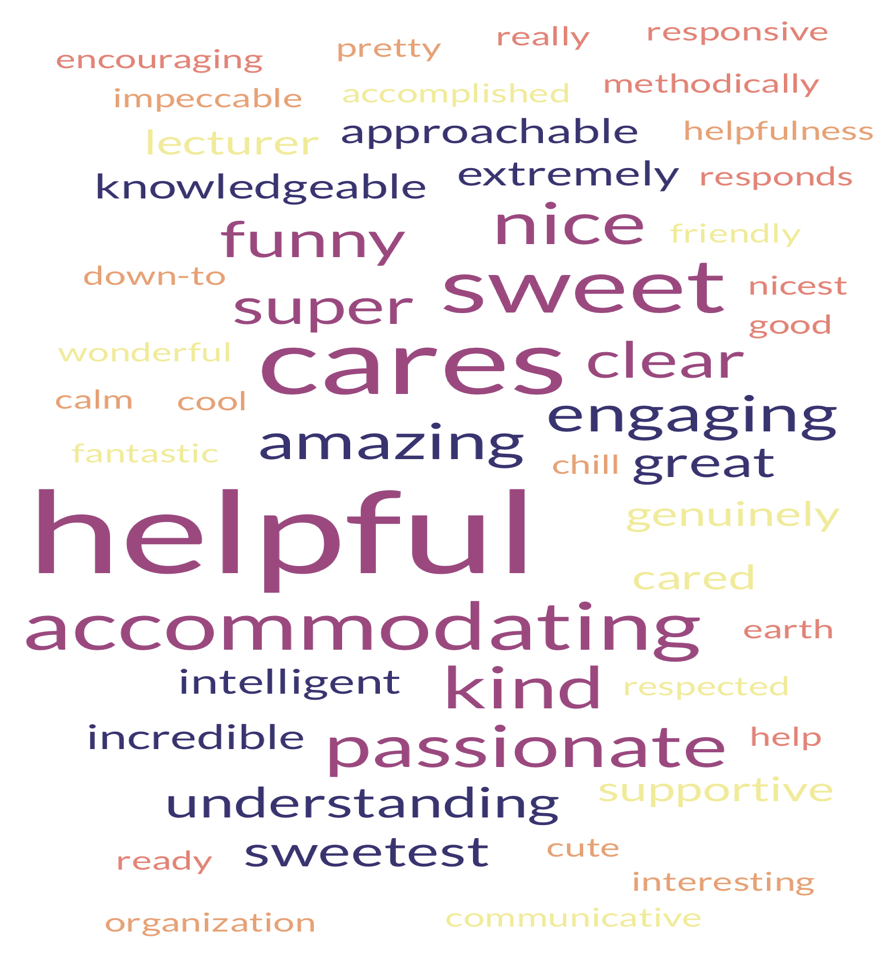

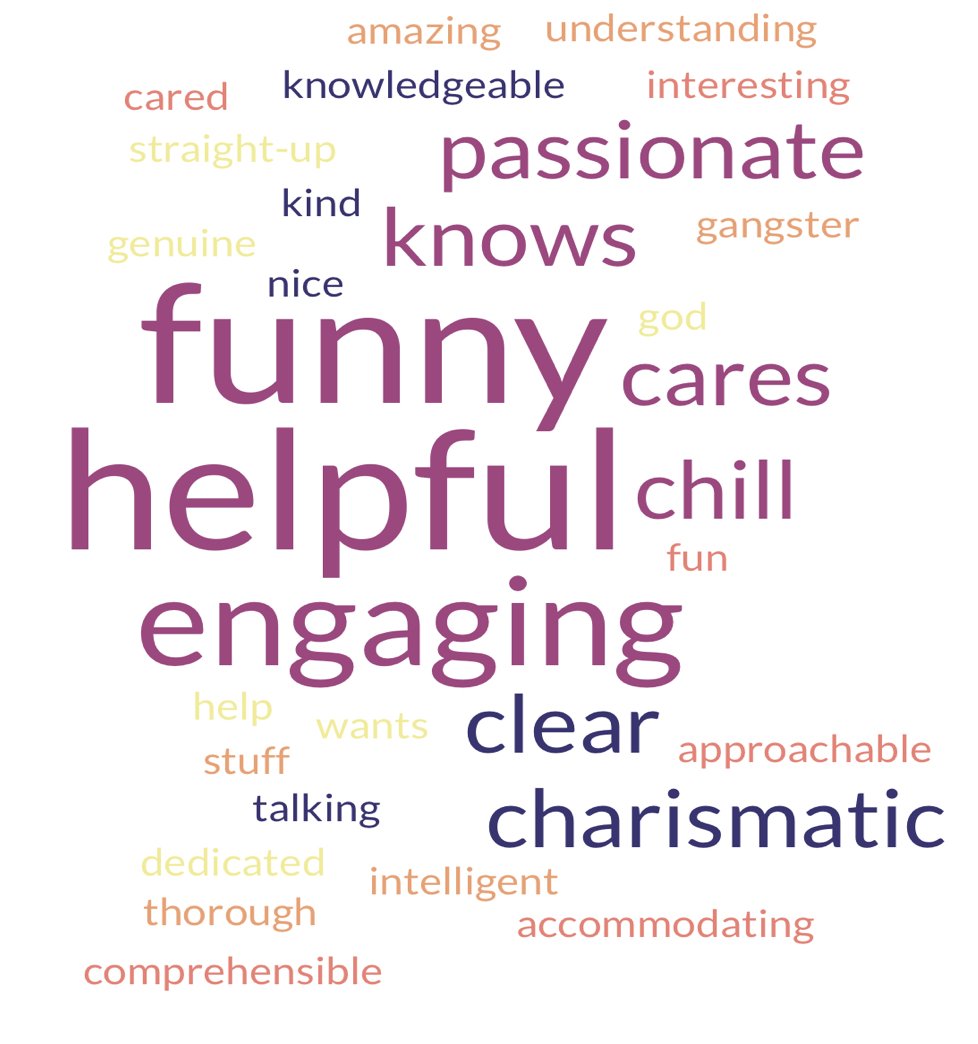

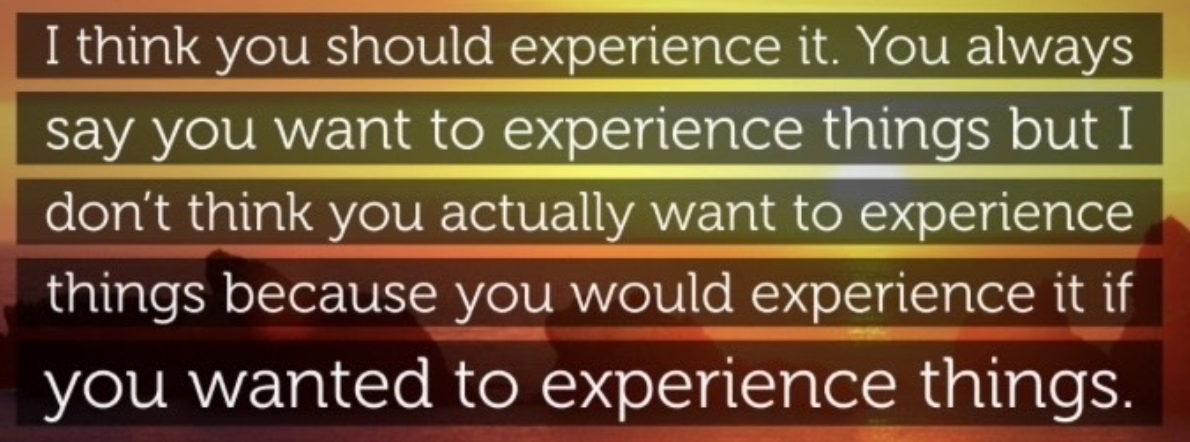

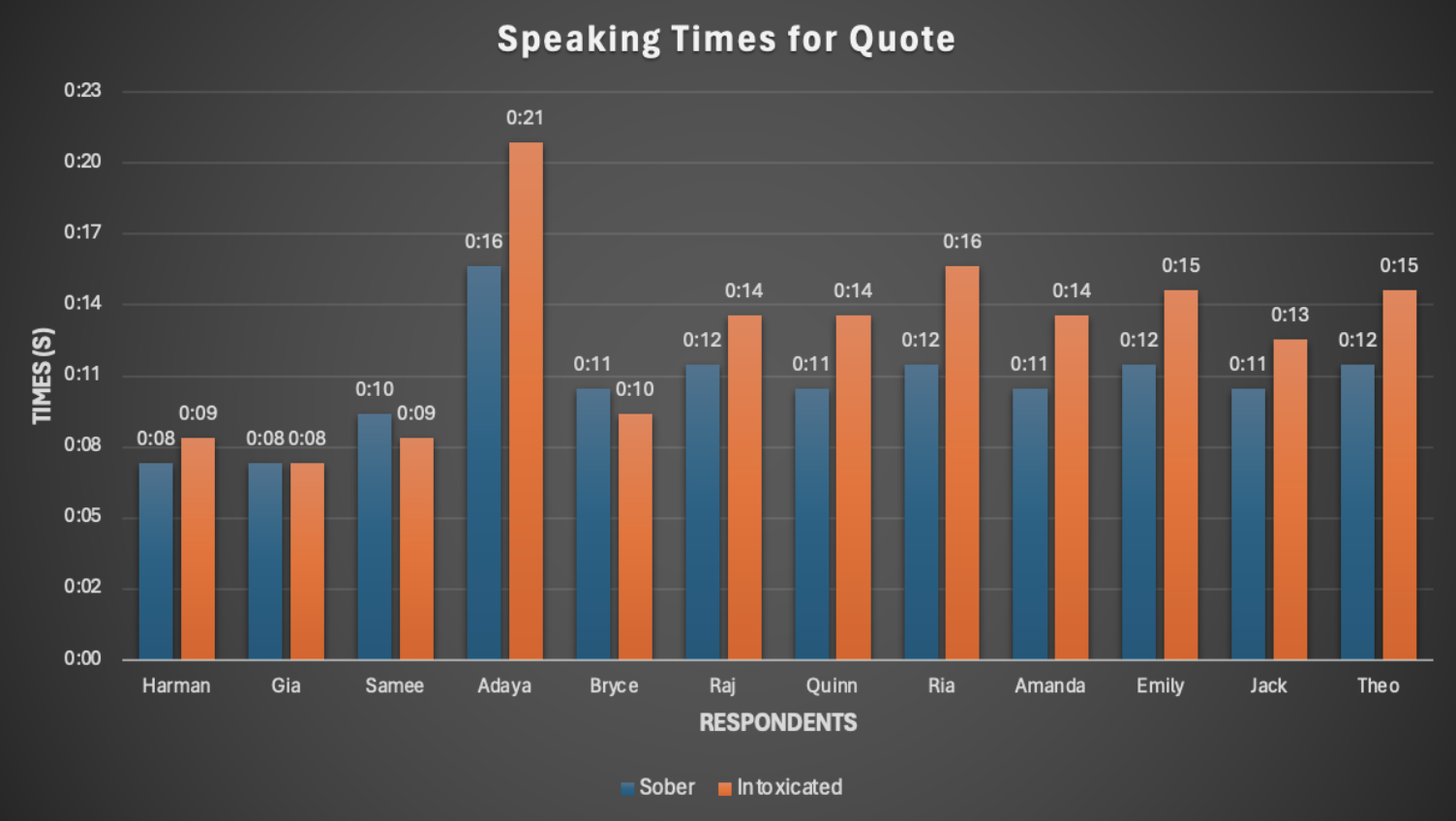

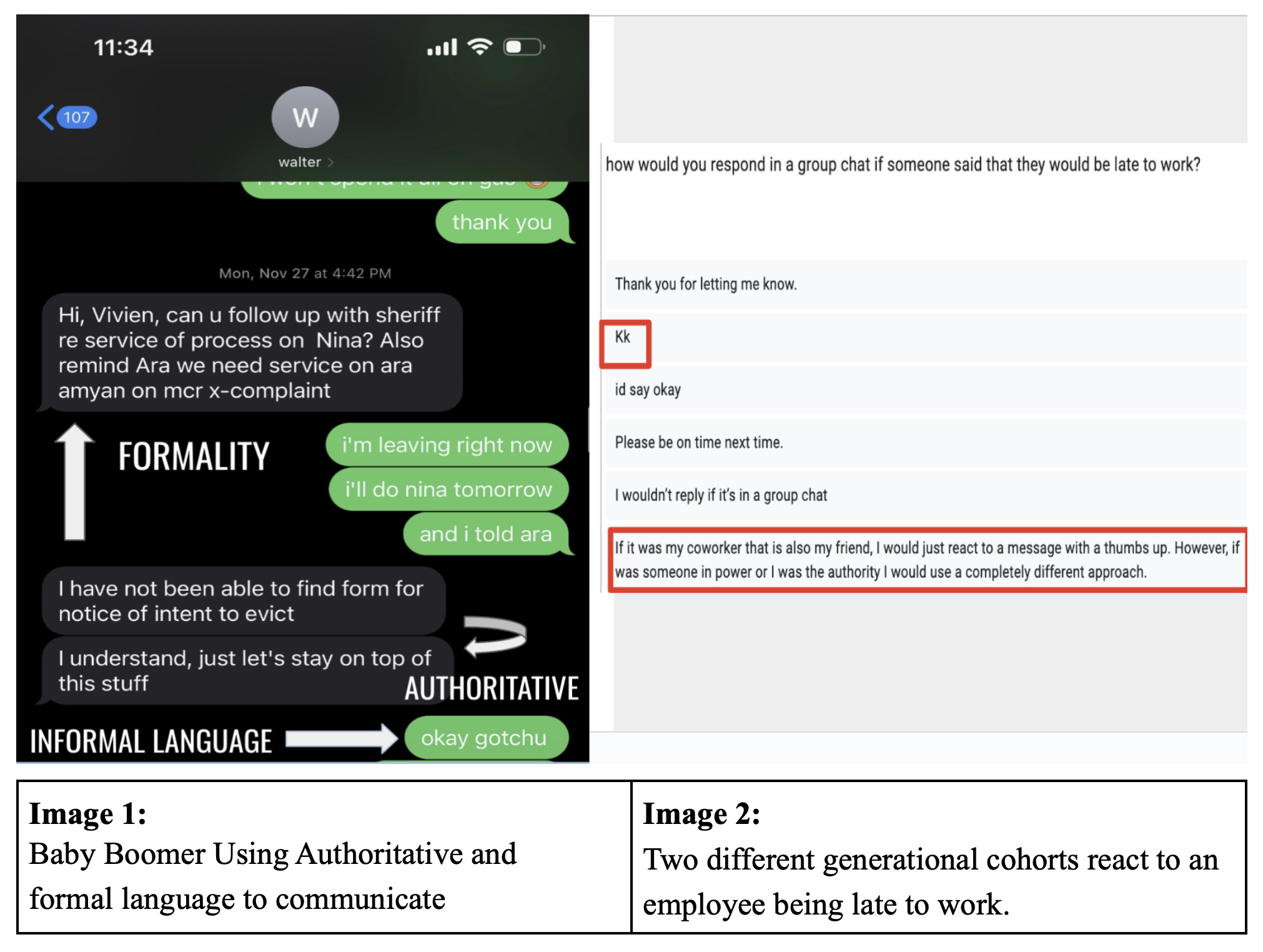

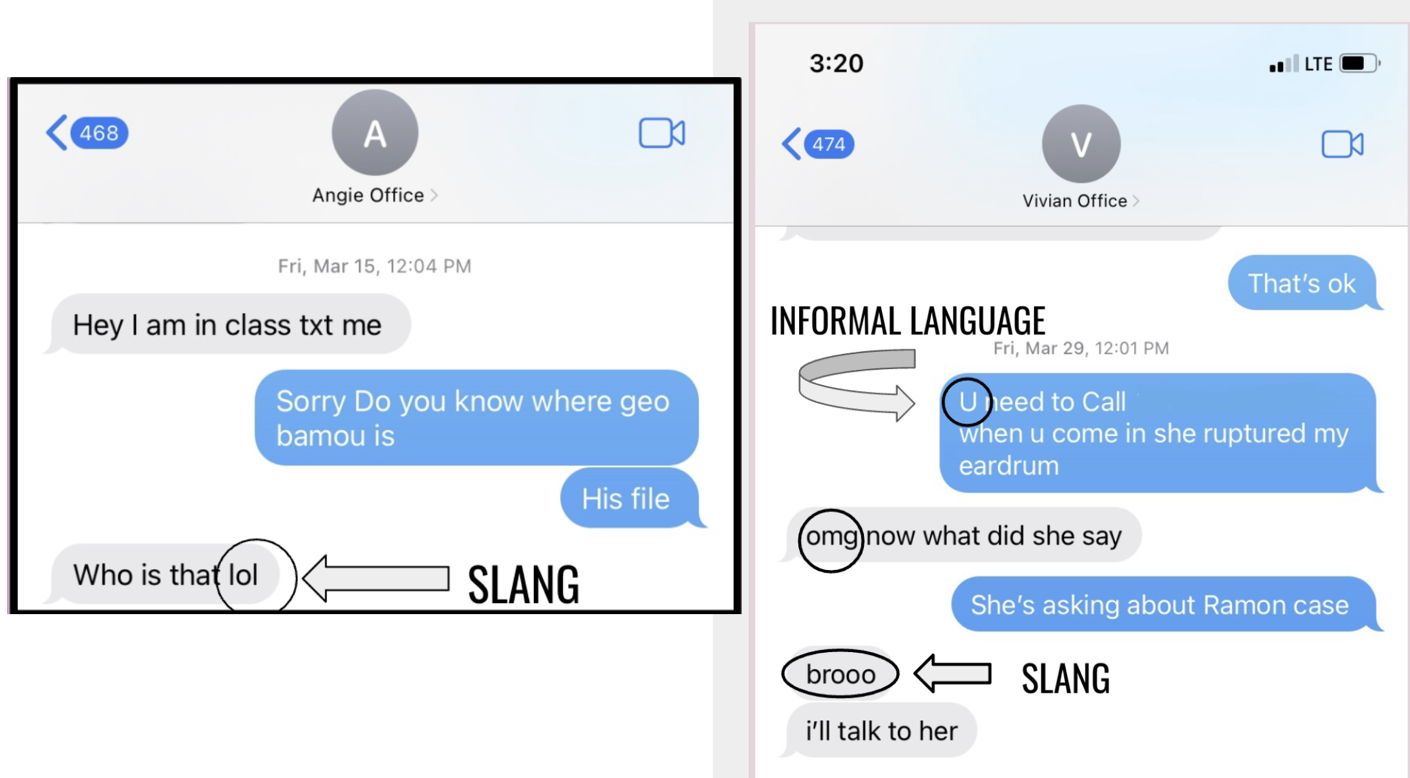

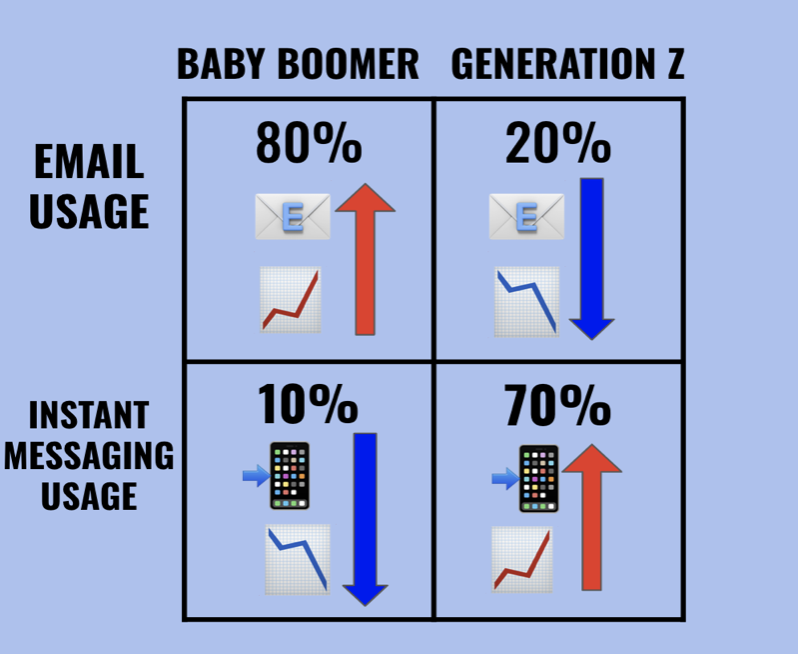

Introduction and Background In the evolving landscape of communication, the distinction between in-person and digital interaction has become a key area of sociolinguistic study. This project investigates how language styles, expressions, and understandings are adapted between these two modes of communication, particularly among college students. The study examines linguistic features such as informality, emoji usage, and turn-taking, shedding light on the nuances of their communication choices. Traditionally, in-person communication has been valued for its richness and immediacy. This mode allows for a wealth of non-verbal cues such as gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice, all of which enrich the communication experience and help in accurately conveying emotions. Face-to-face interactions also foster a sense of connection and immediacy, which are often crucial for forming strong interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, digital communication offers unparalleled convenience and flexibility. Platforms like Snapchat, Instagram, and WeChat have revolutionized how we interact, making it possible to maintain relationships over long distances with ease. The digital transformation of communication has brought about significant changes in the linguistic practices of individuals, particularly young adults. The incorporation of multimedia elements such as images, videos, and emojis attempts to bridge the gap in emotional expression that the lack of physical presence creates. However, these elements, while helpful, often fall short of fully replicating the subtleties conveyed through face-to-face interactions. The gap highlights the potential for misunderstanding and the need for enhanced digital literacy in order to navigate the complexities of modern communication. The primary focus of this study is to assess the preferences of college students (aged 18-22) who regularly engage in both in-person and digital communication. It aims to document their perceived advantages and drawbacks of each mode, particularly in terms of emotional expressiveness and the potential for misunderstandings. Additionally, the study delves into the phenomenon of code-switching — altering one’s language, tone, or style according to the communication platform — which reflects broader cultural identities and adaptability in digital spaces. Methodology To examine the differences in communication styles between in-person and digital interactions among college students, we conducted a thorough survey of students aged 18-22. Our methodology ensured that we collected data from a diverse and representative sample, which is critical for drawing meaningful conclusions. The survey was created with Google Forms, leveraging its accessibility and ease of use to reach a large audience. We divided the survey into three major sections: demographics, communication preferences, and emoji usage. The demographics section gathered basic data such as age, nationality, and primary languages spoken. The communication preferences section explored the participants’ preferred modes of communication, the differences in word and phrase usage between these modes, the ease of conveying emotions, and their awareness of changing language styles or tones. The final section focused on emoji usage, asking about frequency, meanings, and emoji-related misunderstandings. We ensured a diverse participant pool by distributing the survey through social media platforms and student groups, which reached students from a variety of cultural backgrounds and academic disciplines. The survey responses were automatically compiled into a Google Sheets spreadsheet, allowing for efficient organization and preliminary analysis. We calculated frequencies, percentages, and averages for the quantitative data to summarize demographic information and communication preferences, giving us a clear picture of the data’s major trends and patterns. We used thematic analysis to examine qualitative data, particularly open-ended responses about emoji usage and communication preferences. This process involved coding the responses and identifying common themes, which allowed us to gain a better understanding of the participants’ experiences and perceptions. We used this methodology to gain a thorough and nuanced understanding of how college students navigate the complexities of in-person and digital communication. By analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data, we were able to identify key trends and patterns in communication styles, providing valuable insights into the changing landscape of digital communication. The use of advanced data analysis tools and rigorous thematic procedures ensured that our findings were robust and reflective of the diverse experiences within our sample. This methodology not only provided a strong framework for our research, but it also ensured that our findings were based on a diverse and representative sample, adding to the larger conversation about language use and social interaction among young adults. Analysis and Results We were able to attain a total of 30 participants, whose ages were between 19 to 26. Figure 2 shows that the majority of participants were Asians at 73.3%, and the other 26.7% of the participants were American. The results of the survey garnered a better understanding of how college students prefer in-person communication over online conversation. Figure 3 shows that Instagram is the most popular social media platform among college students with 80%. 24 participants use Instagram to communicate with others since Instagram is very common among the younger generation; people can post pictures and send each other direct messages. 13.3% of the participants like to use WeChat, which is because some of them are international students who can easily communicate with their friends in China through the platform. The data from Figure 4 shows a strong preference for in-person communication among participants, with 50% favoring this way over online interactions or a combination of both because they feel more productive communicating in person. On the other side, 23.3% prefer online communication, reflecting a significant proportion that values the convenience and accessibility of digital platforms. Meanwhile, 26.7% of participants are comfortable with both ways, suggesting a flexible communication preference that could be influenced by situational factors. In-person communication is generally considered to be more effective in conveying emotions than text-based communication, with 80% of respondents preferring face-to-face communication. Only 10% of respondents believe that online platforms are effective in conveying emotions, and online platforms are likely to use GIFs and emojis. This suggests that digital interactions are not perceived to be enough to express emotional states, which may lead to a lack of empathy in conversations. Face-to-face interactions remain crucial for a deeper emotional connection, underscoring the limitations of digital platforms in replicating the richness of in-person exchanges. 43.3% of respondents believe that emojis can lead to misunderstandings, while the same percentage of respondents said they do not. This polarization highlights the ambiguity of emojis, which may be interpreted differently depending on individual circumstances and cultural backgrounds. The remaining 13.3% respondents were unsure of their impact. Based on the data collected from our survey, it is evident that emoji interpretations vary significantly among users. An analysis of the responses revealed divergent interpretations of several emojis. For instance, the smiley emoji 😃, conventionally associated with happiness and positivity, was perceived by some participants as conveying creepiness. The skull emoji 💀, which typically signifies extreme laughter, frustration, or affection according to Apple’s official description, was interpreted by respondents as representing extreme fatigue or exhaustion, akin to the expression “I am so tired, I am dying.” Moreover, it was also seen as indicating laughter, albeit more intense and devoid of any undertones, compared to 😭. Notably, the 😭emoji has lead to the most misunderstanding in their online conversation compare to others. 😭, which Apple describes as depicting a face with an open mouth, wailing, and shedding streams of heavy tears, symbolizing inconsolable grief or intense emotions such as uncontrollable laughter or overwhelming joy, was commonly misinterpreted. Participants reported using it in adverse situations, with connotations such as “yikes” or “can’t believe my bad luck,” “need help,” and some even perceived it as laughter accompanied by a sense of embarrassment. The findings from our survey underscore the complexity and variability in emoji interpretations among users, which can be quite different from what they are officially meant to represent. This can sometimes lead to confusion in online conversations. It’s important to remember these differences when using emojis, suggesting a need for greater awareness of contextual differences in emoji usage to avoid misunderstandings and make sure our messages are clear. For additional insights and nuances, the context of the communication also appears to play a critical role in the preferred mode. For instance, for quick updates or logistical arrangements, digital communication is often favored for its efficiency. However, for more complex discussions or sensitive topics, in-person interactions are preferred due to the richer, more nuanced exchange they enable. It is also worth noting that some students reported a gradual shift in their preferences towards digital communication as they adapted to the constraints imposed by recent global events such as the pandemic. This adaptation process reflects the dynamic nature of communication preferences in response to external changes. Based on the data, the majority of college students still prefer and find it more effective to communicate in person, particularly for emotional interactions. The findings indicate that although some students recognize the advantages of online communication, most still believe that in-person contact is more beneficial, especially when it comes to expressing emotions, and students feel more productive since people can get through everything right away. This outcome contradicts our hypothesis, highlighting the complexity of communication preferences among college students. Further analysis shows that communication preferences may vary significantly based on factors like the student’s academic major, cultural background, and prior exposure to diverse communication platforms. Discussion Our findings contradict the idea that generation Z is used to being on online communication platforms. In the article by Janssen (2021), generation Z is often referred to as “digital natives.” They are considered the first generation to grow up entirely in the digital age, influencing their communication habits significantly. They are described as “native speakers” of the digital language of computers, video games, and the internet. Texting and instant messaging are preferred over traditional communication methods like phone calls and emails. Generation Z uses smartphones heavily for personal communication, often choosing texting or messaging apps over voice communication. Despite their preference for texting, generation Z adapts to professional communication norms. For example, they use email extensively at work, despite rarely using it in personal contexts. This indicates flexibility in their communication styles, adapting to different linguistic expectations based on context. Surprisingly, our findings are totally opposite from this perspective of generation Z. For the limitations of the study, while our study focused on college students aged 18-22, this demographic may not fully represent the broader population’s communication preferences. The age group and educational environment might influence communication styles more specific to this demographic, such as familiarity with digital platforms or developmental aspects related to social interactions. Additionally, the study relies heavily on self-reported data, which can introduce bias. Participants might respond in ways they perceive as socially acceptable or based on their aspirational self-image rather than their actual behavior. This can affect the accuracy of data concerning preferred communication modes and the effectiveness of emoji usage in conveying emotions. The phenomenon of code-switching, where individuals adapt their language based on the audience’s cultural and linguistic background, further illustrates the adaptability required in digital communication and highlights the ongoing evolution of language use on these platforms. “Another study conducted by Alfaifi (2013) on intrasentential CS in Facebook comments written by 10 Saudi Arabic-English bilinguals found that intrasentential CS was used with gossip and humor, English was used for academic and technical terms, and Arabic was used for religious topics” (Elhija 357). Digital communication often sees a higher incidence of code-switching, where bilingual or multilingual speakers switch between languages or dialects depending on the audience, topic, or platform. While this can showcase linguistic flexibility, it also highlights the challenges of maintaining cultural nuances in digital communication, which may not always provide the contextual cues necessary for appropriate language use. This underscores the persistent value of traditional communication methods in an increasingly digital world and suggests that digital platforms still need to evolve to support the subtleties of human emotion and expression fully. Conclusion Our study began with the hypothesis that college students would prefer online communication over in-person interactions, primarily due to the flexibility and reduced social anxiety that digital platforms are presumed to offer. This hypothesis was rooted in the belief that the modern digital environment, with its asynchronous communication and absence of physical presence, might alleviate the pressures associated with face-to-face interaction. The data, however, painted a different picture. Contrary to our expectations, 50% of the participants clearly preferred to communicate with their classmates in person, appreciating the depth of emotion and clarity that comes with real-time, face-to-face interactions. Only 23.3% expressed a preference for online communication. This finding suggests that despite the convenience of digital platforms, they are insufficient for fulfilling all communicative needs, especially those that involve emotional depth and nuance. The results of our study provide a nuanced understanding of how college students navigate the complexities of digital and in-person communication. While digital platforms offer undeniable convenience and flexibility, our findings suggest that they do not fully replicate the emotional richness and immediacy of face-to-face interactions. Half of the participants expressed a preference for in-person communication, particularly valuing its effectiveness in conveying emotions — a fundamental aspect of human interaction that digital platforms have yet to fully capture. Moreover, our investigation into emoji use revealed a balanced scenario: emojis enhance textual communication by adding emotional depth, yet they also lead to misunderstandings in nearly half of the cases reported. This indicates a significant gap in how emotional nuances are perceived and understood in digital contexts. By realistically assessing these results, we acknowledge that while digital communication technologies have transformed how we connect and interact, they are not a complete substitute for in-person interactions. Instead, they are a complementary medium that requires further refinement to meet the emotional and contextual needs of users fully. Future research should focus on developing and testing new technologies that can better accommodate the complex dynamics of human communication, bridging the gap between the efficiency of digital communication and the emotional depth of face-to-face interactions. As a result, this study not only challenges previous assumptions about digital communication preferences but also enriches our understanding of how young adults toggle between digital and real-world interactions, shaping their social identities and relationships in the process. References Brenda Danet, Susan C. Herring, Introduction: the Multilingual Internet, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 9, Issue 1, 1 November 2003, JCMC9110, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2003.tb00354.x. Defede, N., Magdaraog, N. M., Thakkar, S. C., & Bizel, G. (2021). Understanding How Social Media Is Influencing the Way People Communicate: Verbally and Written. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 13(2), 1-. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v13n2p1. Ehrensberger-Dow, M., & Granger, S. (2019). “English as a Lingua Franca in Digital Communication: Diverse Voices, Similar Scripts?” Lexis Journal in English Lexicology, 14, 193-217. https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis.1831. Elhija, D. A. (2023). Code Switching in Digital Communication. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 13, 355-372. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2023.133021. Psych Minds. (n.d.). Communication: Online vs. Face-to-Face Interactions. Retrieved from https://psychminds.com/communication-online-vs-face-to-face-interactions/. Schroeder, J. (2019). Two Social Lives: How Differences Between Online and Offline Interaction Influence Social Outcomes. https://escholarship.org/content/qt94n9w8b9/qt94n9w8b9_noSplash_293949a5e051fffc8e1fdcc9ffc168c4.pdf?t=qdtezb. Zhao, Y. (2021). The Impact of Digital Media on Language Styles and Communication Methods Based on Text, Image, and Video Forms. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378739166_The_Impact_of_Digital_Media_on_Language_Styles_and_Communication_Methods_Based_on_Text_Image_and_Video_Forms. D. Janssen and S. Carradini, “Generation Z Workplace Communication Habits and Expectations,” in IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 137-153, June 2021, doi: 10.1109/TPC.2021.3069288. Appendix Our survey link: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScCFoDiKMbxxYVWXmxPAEwQIKfTjg8mx1qtZFL9oA55R9WpPg/viewform?usp=sf_link