Lights, Camera, Flirtation: An Analysis of Male and Female Verbal Flirting Techniques, As Represented in 5 Romantic Comedies from 1989–2023

Sherry Zhou, Amo O’Neil, Jared Ramil, Juliana Rodas, Thalia Rothman

Our paper seeks to analyze the ways in which flirting and romantic communication has changed, in regards to both gender and societal norms. In doing so, we collected and analyzed data regarding the frequencies and distribution of flirting between main characters of five different romantic comedy movies. We collected data pertaining to four variables: frequency of compliments, pitch change from, sexual jokes, and meaningful questions. Our analysis of the data revealed a number of observations indicative of s in present day society. Most significantly, we observed an increase of female or more female presenting characters initiating flirtation over time, a reflection of changing gender norms in society. With the rise of digital media and the Internet, online content such as movies have become more impactful to the way society processes social norms. Our study calls for continued analysis of the reflections of media representations and narratives onto society, and vice versa.

Introduction and Background

The societal obsession with flirtation and romance permeates modern life at every level. It is the subject of conversations with friends, podcasts, television, books and social media posts. When it comes to how exactly to flirt, most resort to clichés like batting eyelashes and using bad pickup lines. Our research aims to analyze the ways in which the media portrays successful romance, specifically in romantic-comedy movies. Through study, we sought to understand societal shifts in romantic dynamics as portrayed in popular media and their potential implications on real-life interactions.

Flirting is a broad category of physical and verbal communication, and men and women often favor very different strategies. Gender divides in courtship can be traced through time — a study of 19th century love letters showed men expressing their passion through poetic language and elaborate vocabulary while women were expected to be reserved and polite (Wyss 2008). Modern studies showed women tend to have a more reserved flirting style, and men tend to be more playful (Hall and Xing 2015). Women were also found to be more polite with the opposite gender (Cabrera 2022), and had more interest in men’s personality traits, while men focused on women’s physical appearance (Apostolou and Christoforou 2020). Finally, gender roles were found to be strongly predictive of flirtation styles among men and women, though men were also strongly influenced by sexual orientation (Clark, Oswald, and Pedersen 2021).

Our research delves into the evolution of verbal flirting styles between male and female characters depicted in enemies-to-lovers romantic comedies from 1989 to 2023. We hypothesized that time would reveal a less strict gender divide in flirting methods; in particular, we expected female leads to be more direct with sexual comments and male leads to give more personality-related compliments and ask more questions.

Methods

Our research seeks to answer the following question: How have male and female verbal flirting styles portrayed in romantic comedies changed over time? In doing so, we watched and analyzed five different romantic comedies that spanned several decades ranging from the 1980s to the 2020s: When Harry Met Sally (1989), 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), The Proposal (2009), Set It Up (2018), and Red, White, and Royal Blue (2023) (LGBTQ+ case study).

While watching these films individuals, we noted the frequencies and distribution of four specific verbal flirting approaches, our variables, expressed by the romantic leads:

- Compliments: Film scenes containing romantic leads complimenting each other based on physical attractiveness or personality.

- Voice Pitch Changes: Noticeable pitch changes among the romantic interests were documented (i.e., whether a character’s voice went lower or higher), excluding natural vocal changes.

- Sexual Comments: Scenes where characters exchanged sexual remarks to each other. (e.g. lewd remarks, provocations)

- Questions: Questions that were asked, as a means for the romantic leads to familiarize each other (e.g. discussions of one’s past life, interests)

Our study we utilized the content analysis research method to quantify the occurrence of these four variables between the main characters of each film. Using the criteria above, we documented the frequency of each variable, and labeled which characters expressed them. Next, we determined which flirting style was mostly preferred by either men or women, as well as examining how these patterns have evolved over time. In the case study of “Red, White, and Royal Blue,” the romantic lead, Prince Henry, is portrayed as a “bottom,” indicating his flirting techniques as more feminine. The data from this film was analyzed to determine whether flirting patterns translated to heterosexual relationships.

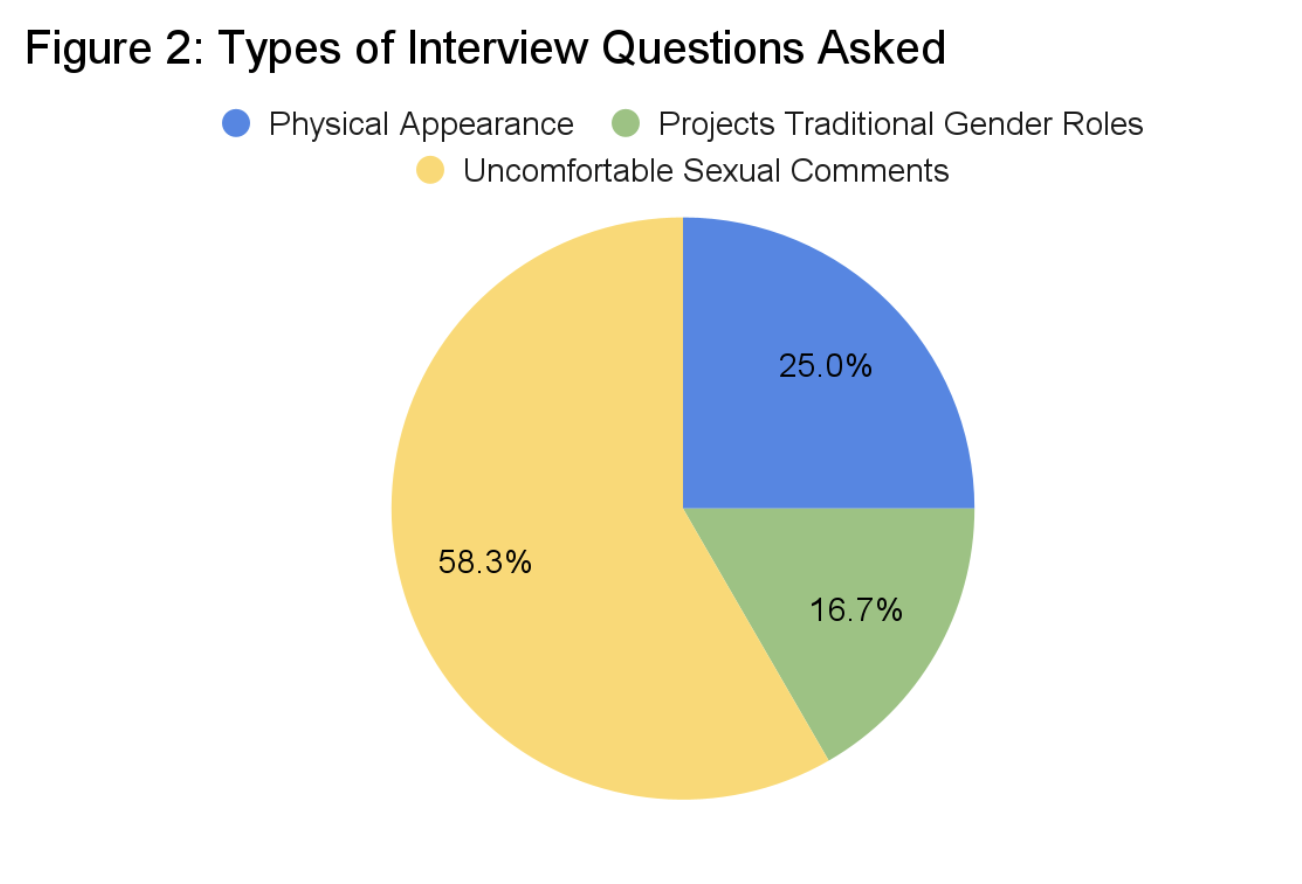

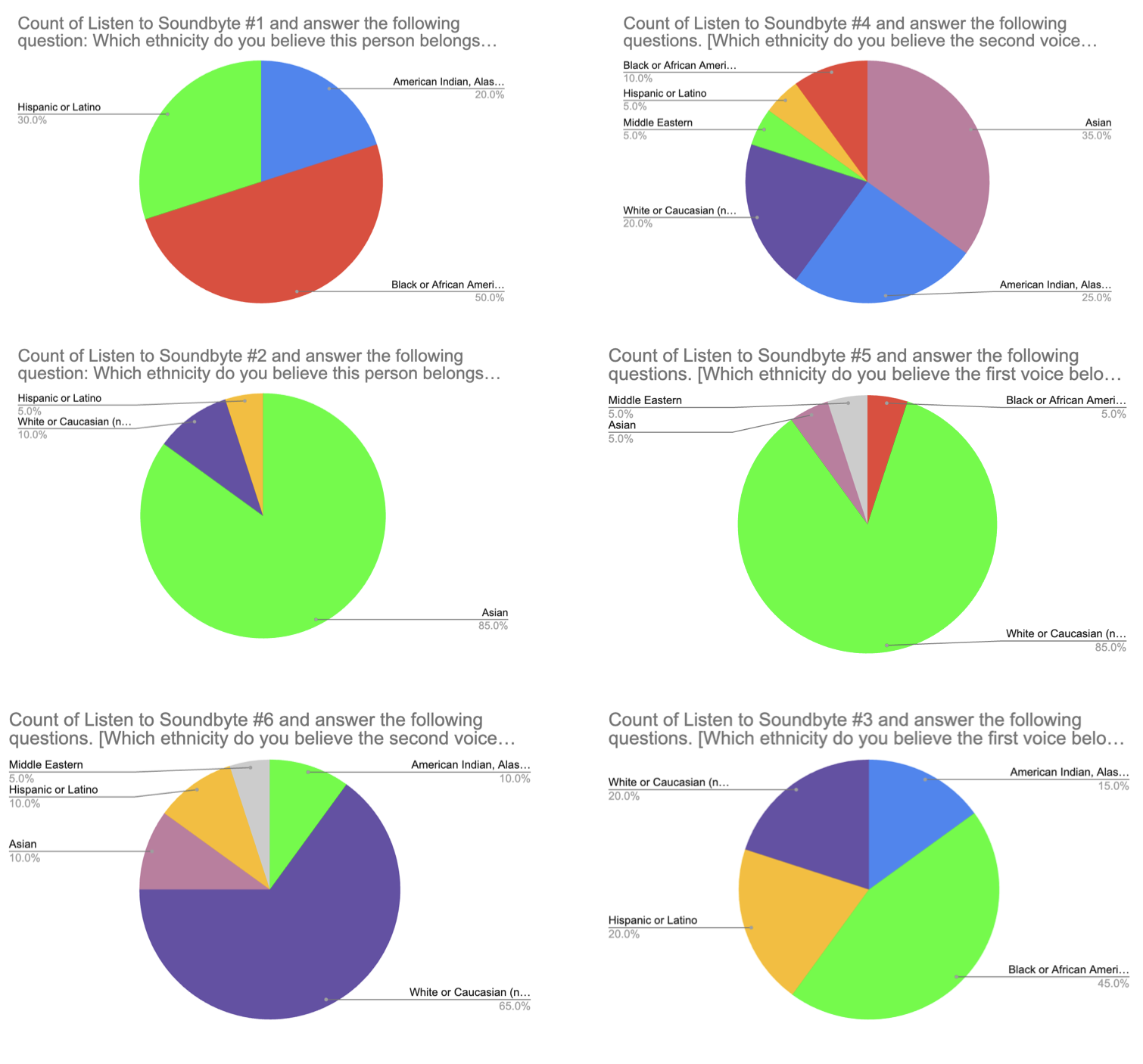

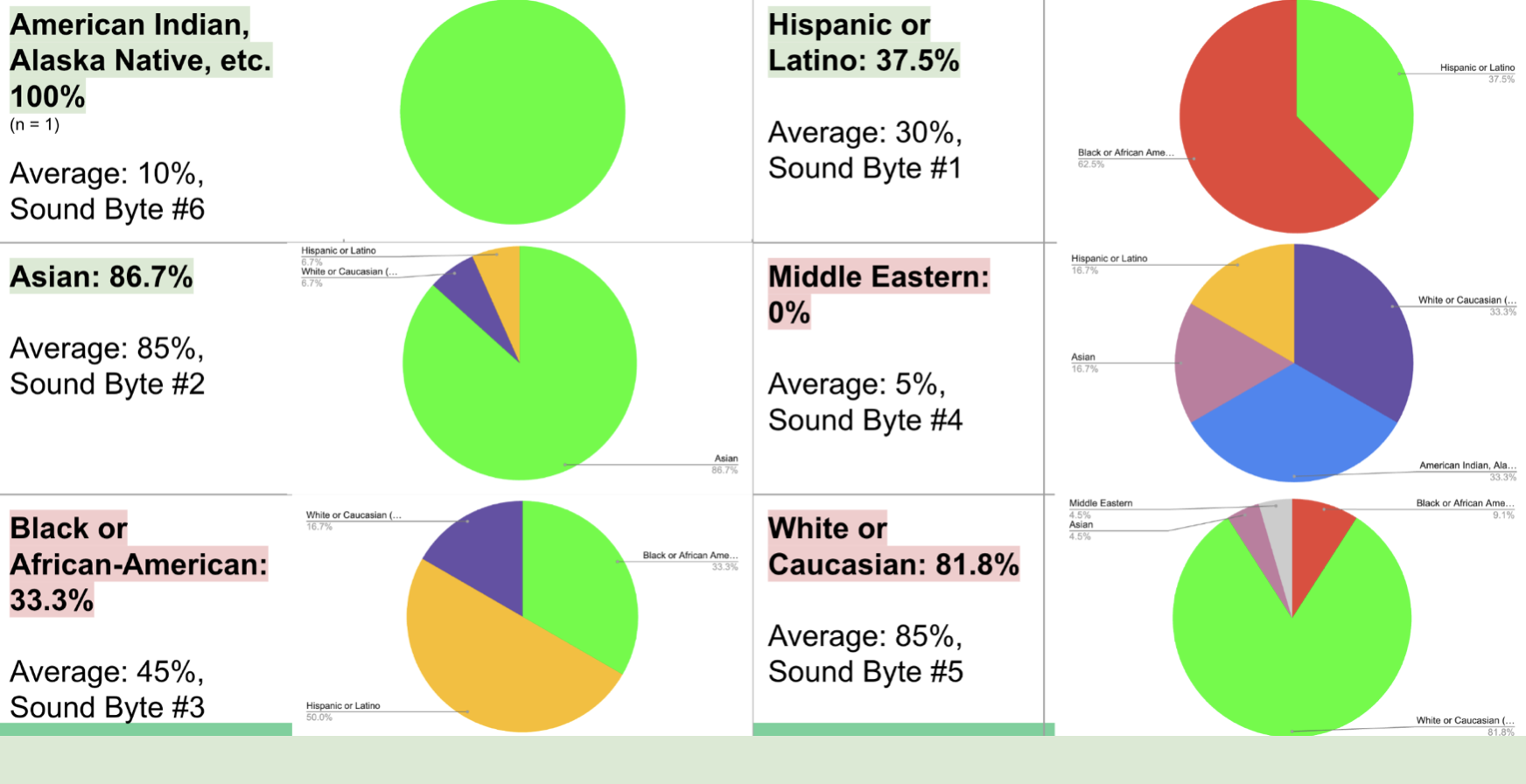

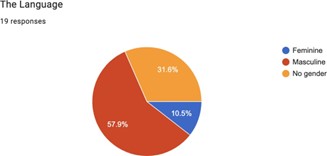

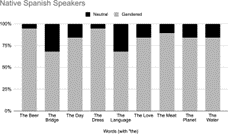

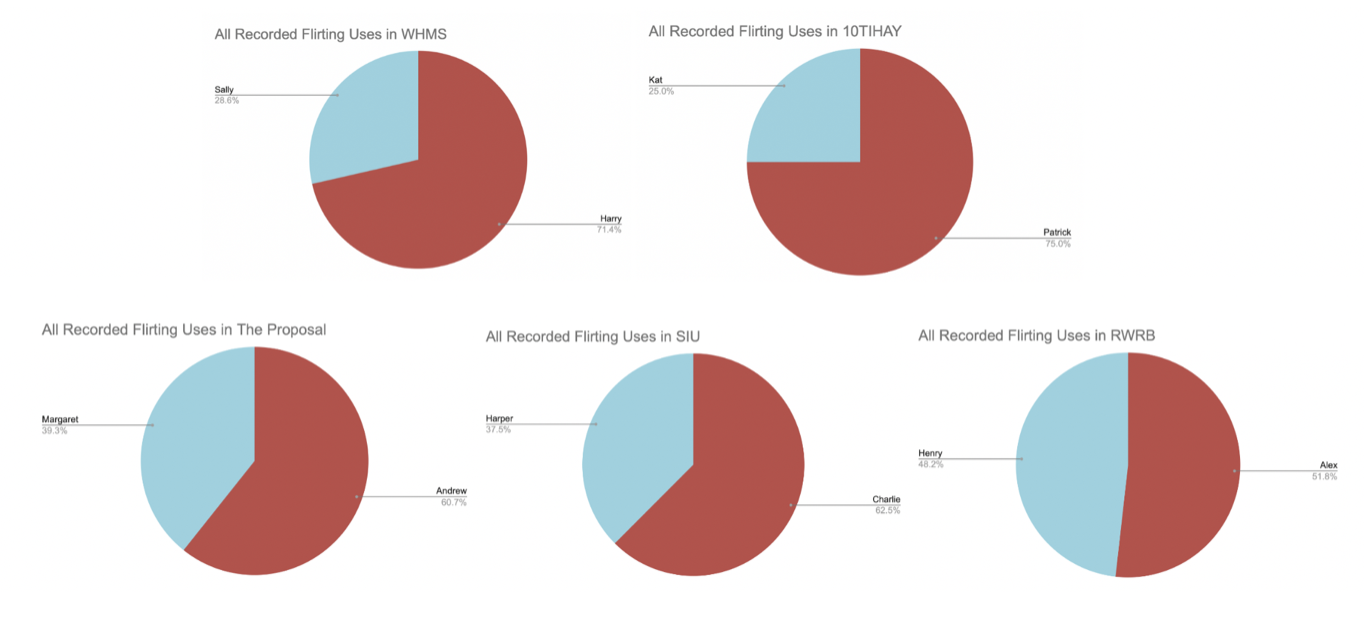

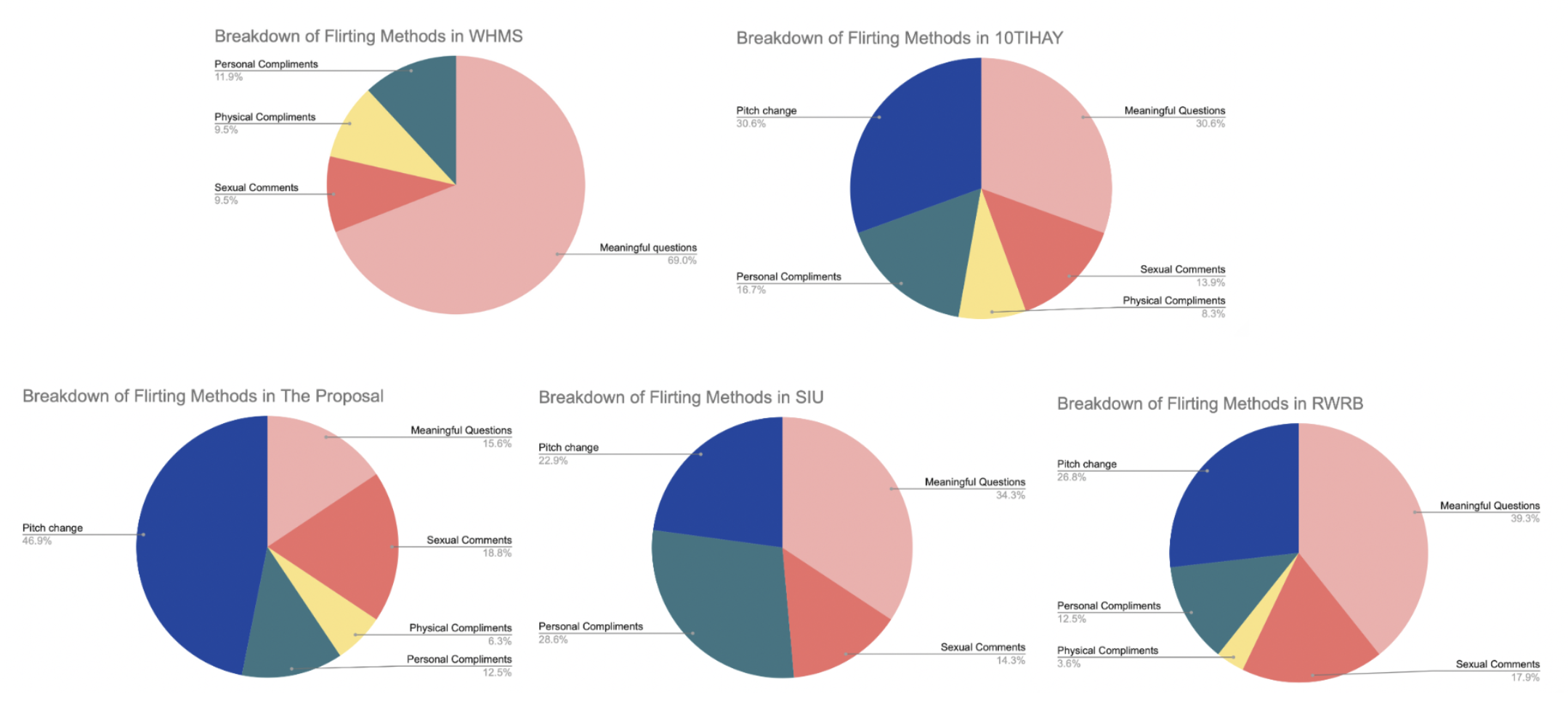

To visualize our results, we formulated our data into two types of pie charts, both in percentages. As can be seen in Figure 2, the first chart documented gender based distribution in flirting: how frequently each character utilized all flirting styles throughout the film. The second chart, Figure 3, depicted variable distribution, showing how regularly each of the four flirting techniques that we observed was used in each film.

Results and Analysis

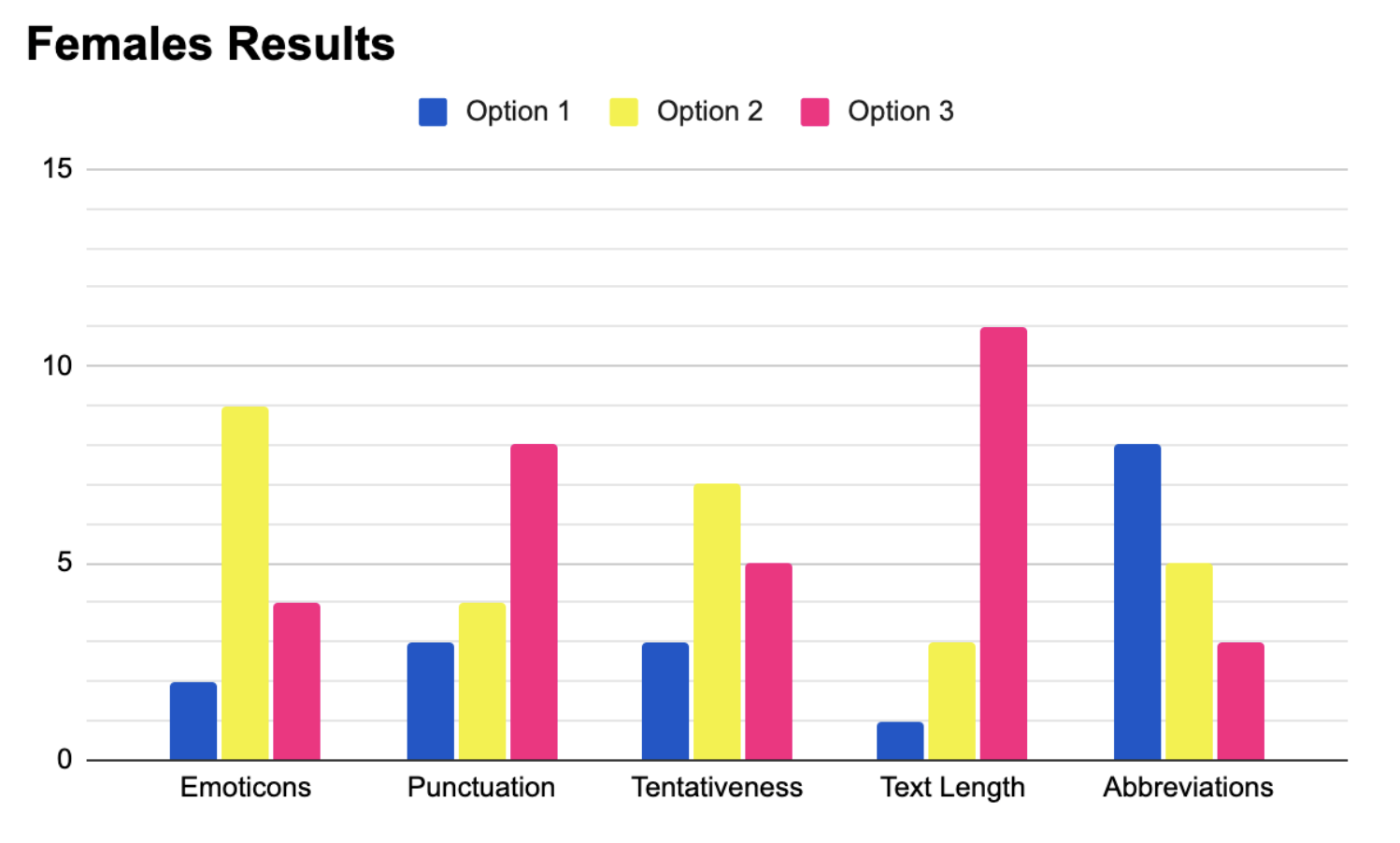

The results of our study on the evolution of verbal flirting styles in romantic comedies from 1989 to 2023 reveal significant trends that reflect broader societal shifts. The total instances of verbal flirting varied significantly across the movies, with “Red, White, and Royal Blue” (2023) having the highest number of recorded instances (56), followed by “When Harry Met Sally” (1989) with 42.

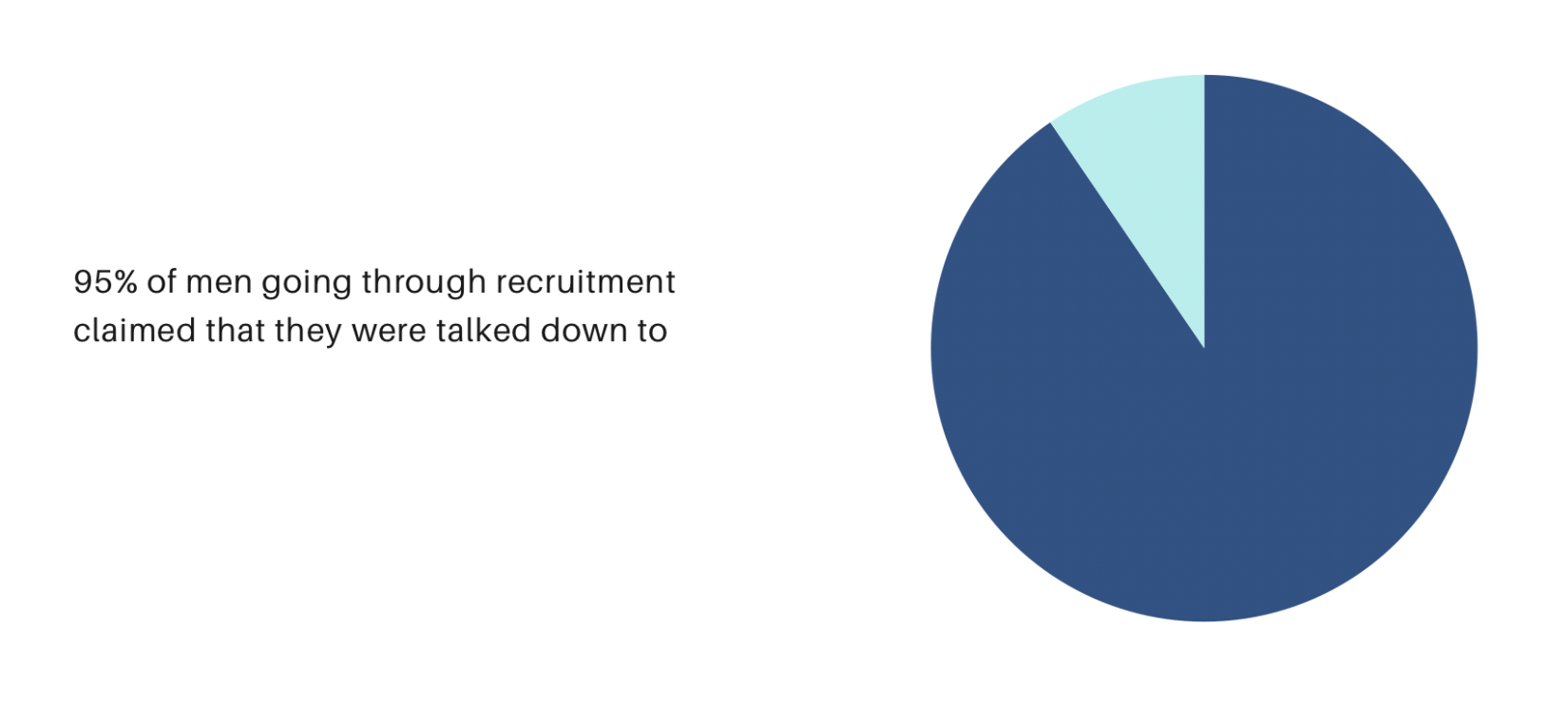

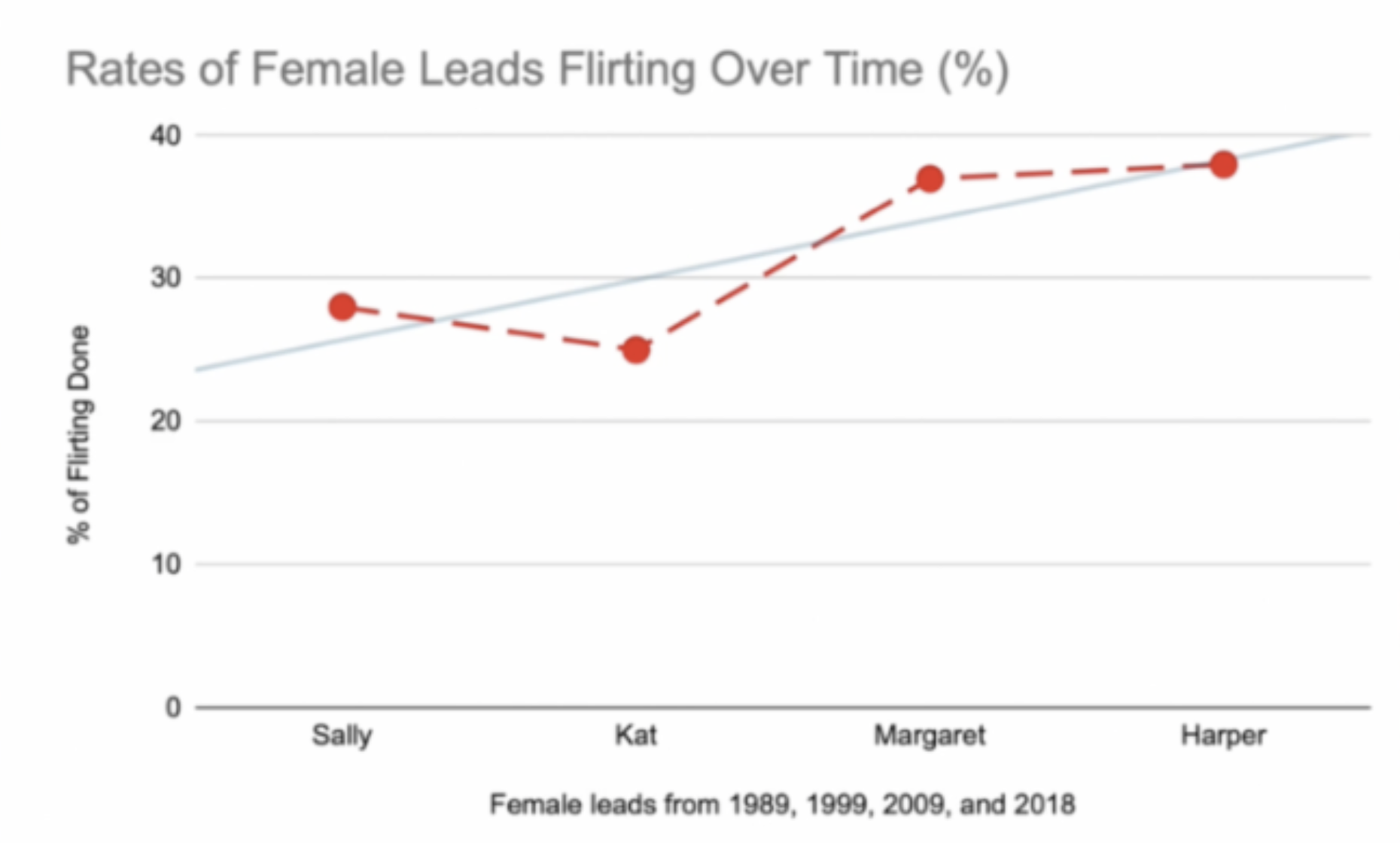

Figure 1: Rates of Female Leads Flirting Over Time

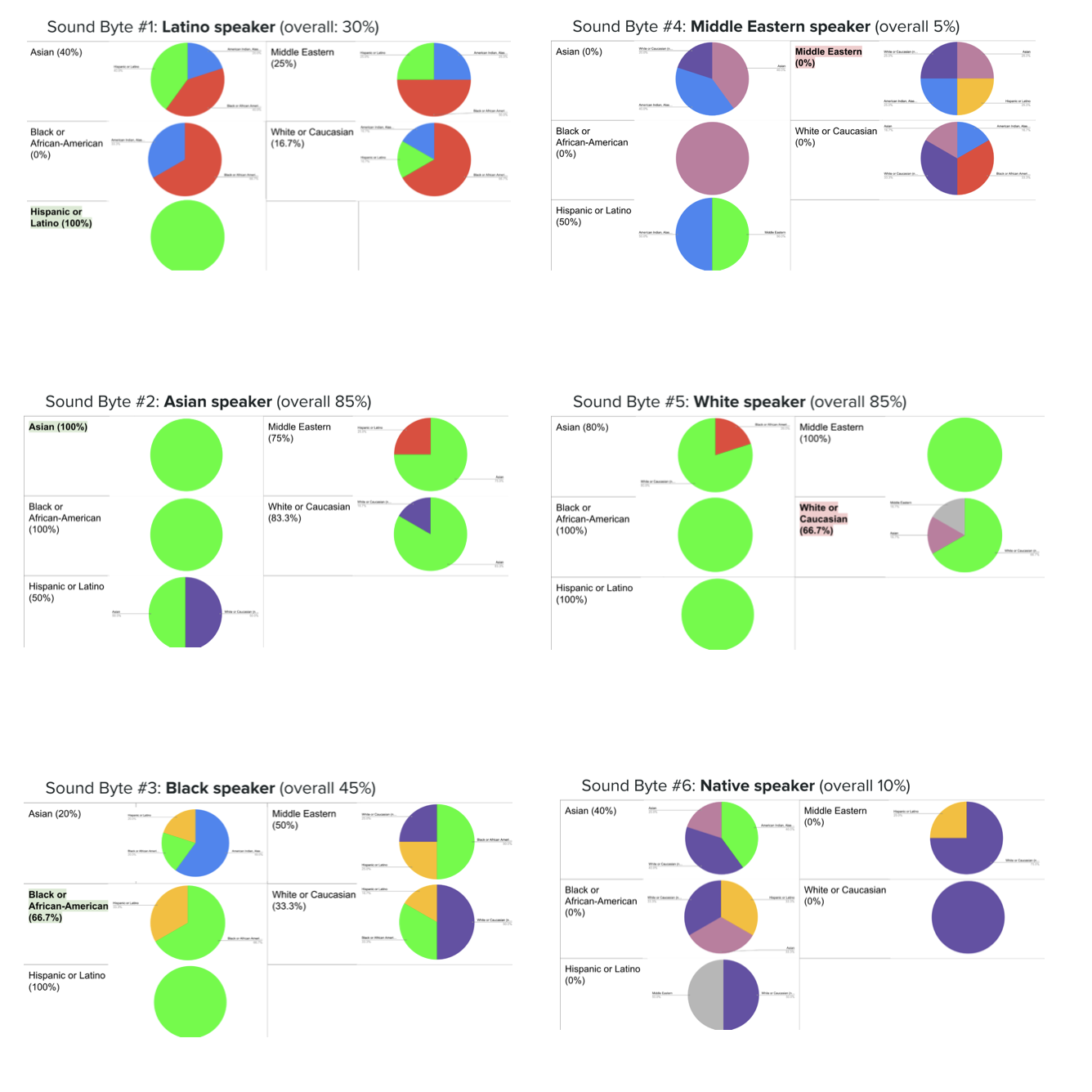

As can bee seen in Figure 2, Men consistently had higher instances of flirting than women in heterosexual relationships, indicating a persistent gender disparity. For example, Harry had 30 recorded instances compared to Sally’s 12, and Andrew had 17 instances versus Margaret’s 14. Although there was a slight increase in the ratio of women’s flirting over time, as can be seen in Figure 1, men still dominated the number of recorded instances. “Red, White, and Royal Blue” (2023) stands out as an exception, with a nearly equal distribution of flirting instances between the male leads, Alex and Henry, who had 29 and 27 instances, respectively.

Figure 2: Gender Based Distribution of Flirting

Figure 3: Variable Distribution of Flirting

Our study also revealed trends in the types of flirting used. As can be seen in both figures 2 and 3, meaningful questions (MQ) showed fluctuating popularity, with men generally asking more questions than women. Harry asked the most questions (18), while Andrew asked the fewest (1). Among women, Sally stood out with 11 MQs, the highest recorded for female characters. The use of sexual comments increased over time, becoming more prevalent in films like “The Proposal” and “Red, White, and Royal Blue.” Physical compliments saw a decline, with women rarely complimenting men’s appearances. Sally was the only woman who did so, once, while men also showed a decreasing trend. Conversely, personal compliments became more popular, with “Set It Up” having the highest number of personal compliments among the movies analyzed. The use of pitch changes as a flirting method varied, showing no clear trend over the years.

A closer examination of the data reveals some nuanced patterns. For instance, in “10 Things I Hate About You” (1999), Patrick had 27 total recorded instances of verbal flirting, while Kat had 9. Patrick’s flirting included a mix of MQs, sexual comments, physical and personal compliments, and pitch changes. Kat’s flirting style included MQs and pitch changes, with no recorded sexual comments or physical compliments. In “The Proposal,” Andrew had 17 instances of verbal flirting, with a significant use of sexual comments and pitch changes, while Margaret had 14 instances, using more MQs and pitch changes.

In “Set It Up” (2018), Charlie had 23 recorded instances of verbal flirting, using MQs, sexual comments, and a significant number of personal compliments. Harper had 12 instances, also using MQs and pitch changes, with a balanced mix of flirting styles. “Red, White, and Royal Blue” showed a unique pattern with Alex and Henry almost equally splitting their flirting instances. Both characters used MQs, sexual comments, physical and personal compliments, and pitch changes, reflecting a more balanced and modern portrayal of romantic interactions.

Overall, the study indicates a shift towards more balanced and diverse representations of flirting styles in romantic comedies. While traditional gender roles are still evident, the increasing representation of women engaging in flirting and the balanced portrayal in “Red, White, and Royal Blue” suggest a trend towards more equal interactions. The rise in sexual comments and personal compliments points to a trend towards more open communication in romantic relationships. These results largely reflect the shift in societal gender norms, which have, in recent years, changed to emphasize female empowerment and gender equality. Our results also reflect the ways in which modern day society has become more accepting of previously frowned upon topics, such as homosexuality and sexual intercourse.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research delves into the evolution of verbal flirting styles in romantic comedies from 1989-2023, revealing significant trends and changes that reflect broader societal shifts. Understanding these changes is crucial because media representations influence real-life perceptions and behaviors. Relationships are fundamental to our lives— they shape our experiences, influence our well-being, and give us a sense of connection and belonging. As media consumers, it is essential to be vigilant about the content we consume and the messages they convey. By critically engaging with media, we can protect our relationships from being impacted by unrealistic or harmful portrayals.

Additionally, these findings can benefit various groups. In the entertainment industry, writers, directors, and producers can use our insights to create more authentic romantic interactions that resonate with modern audiences. By understanding these evolving trends, they can develop characters and storylines that better reflect contemporary relationships. To improve communication and foster healthier romantic interactions, media professionals should strive for authenticity and diversity in portraying relationships— avoid falling back on outdated gender stereotypes and instead, reflect on the complex, evolving nature of modern romance. Educators in gender studies, communication, and media studies can build on our research to explore further how media influences societal perceptions of gender roles and relationships. They should integrate discussions of media representation into curricula on gender and communication, using film examples to illustrate the impact of societal changes on interpersonal dynamics. Our findings provide a foundation for examining the interplay between media representation and real-life communication styles. Individuals can benefit from this research by reflecting on their own communication styles and the societal norms they perpetuate. Increased awareness can foster more inclusive and egalitarian interactions in personal relationships. Additionally, recognizing and challenging the stereotypes depicted in films can help audiences consider how stereotypes might influence their own perceptions and behaviors in relationships.

By leveraging these insights, we hope to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of romantic communication and support the ongoing evolution towards more inclusive and representative portrayals of relationships in media. This not only enriches the storytelling in romantic comedies, but also promotes healthier perceptions of romance and interpersonal relationships in real life.

References

Apostolou, M., & Christoforou, C. (2020). The art of flirting: What are the traits that make it effective?. Personality and Individual Differences, 158, 109866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109866

Cabrera, L. (2022). Quantitative and qualitative analysis of politeness and gender effects in romantic comedies [Doctoral dissertation, Trinity College Dublin]. Trinity’s Acess to Research Archive, Centre for Language and Communication Studies (Theses and Dissertations).

Clark, J., Oswald, F., & Pedersen, C. L. (2021). Flirting with gender: The complexity of gender in flirting behavior. Sexuality & Culture, 25(5), 1690-1706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09843-8

Hall, J.A., Xing, C. (2014). The verbal and nonverbal correlates of the five flirting styles. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 39(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-014-0199-8

Wyss, Eva. (2008). From the bridal letter to online flirting: Changes in text type from the nineteenth century to the internet era. Journal of Historical Pragmatics, 9(2), 225-254. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhp.9.1.04wys.