Influencer Speech and Indexicality

Shogo Payne, Olivia Brown, Jade Reyes-Reid, Ricardo Muñoz, Priscella Yun

Stereotypically, people consider TikTok influencers to be vapid and unimportant. However, through our research on the language of TikTok influencers, we have found that through particular lexical choices, influencers establish their niche within the beauty industry by appealing to the emotions of viewers, becoming vessels for product promotion and marketability. Our work has proven that the greater frequency of inclusive and second-person pronouns, as well as language heavily using imagery and hyperbole, is the key to success for beauty influencers. We compare videos from five of TikTok’s most popular beauty influencers to see if our targeted lexical features can be shown to not only correlate with an increase in popularity on the platform but also to engage viewers as part of an exclusive community. Creators and brands will benefit from awareness of these linguistic tools’ ability to promote their message and products, while also giving them linguistic factors to consider in terms of marketing.

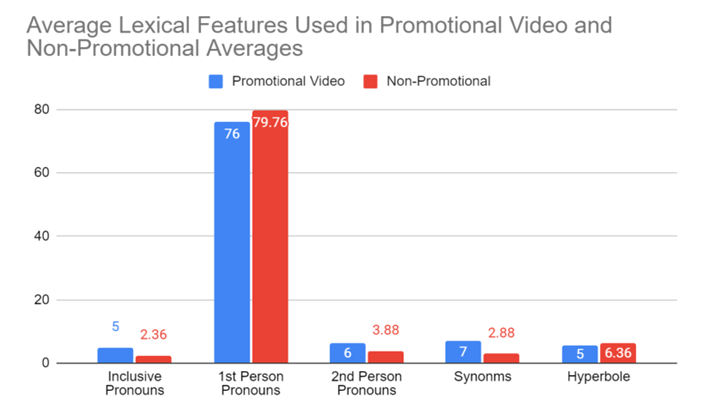

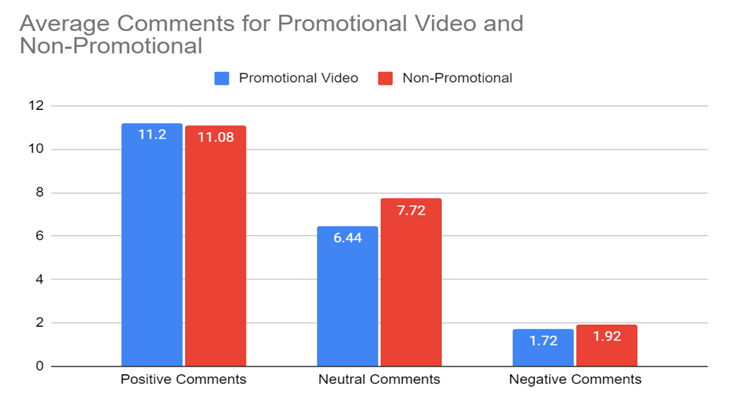

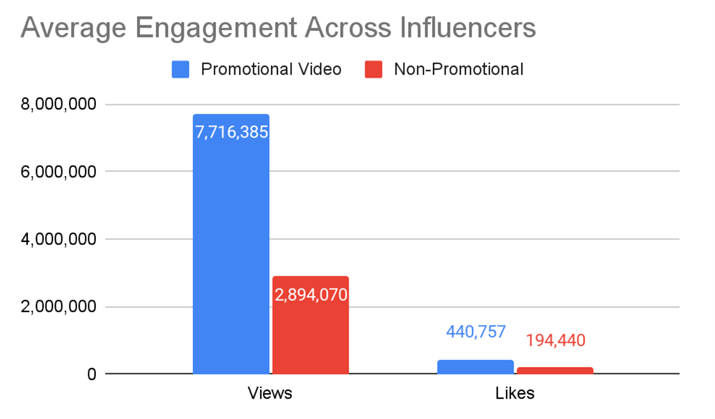

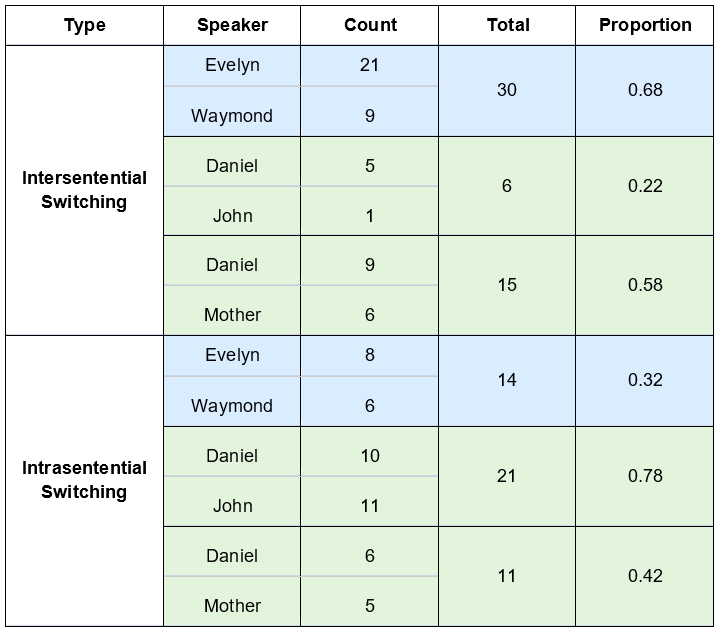

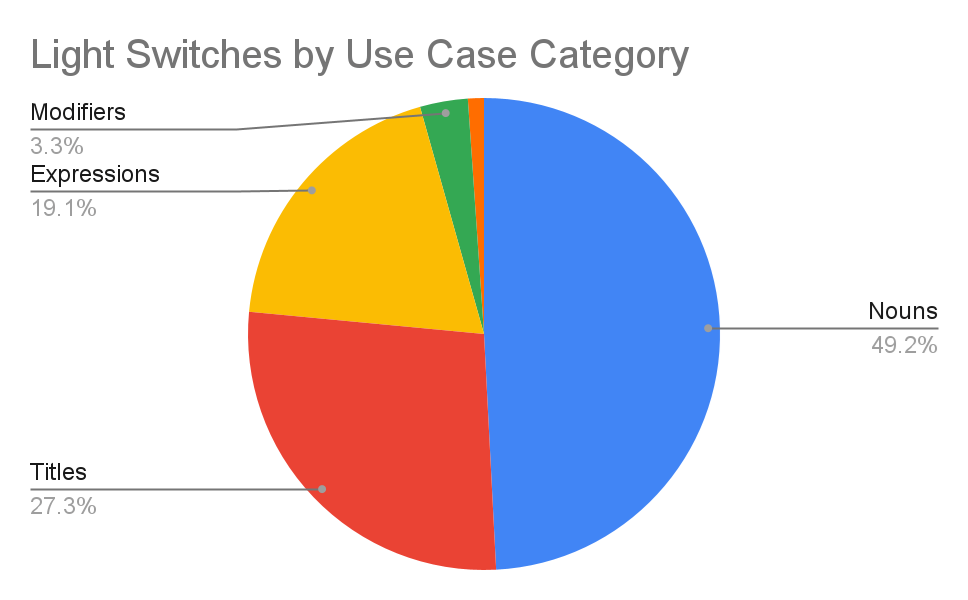

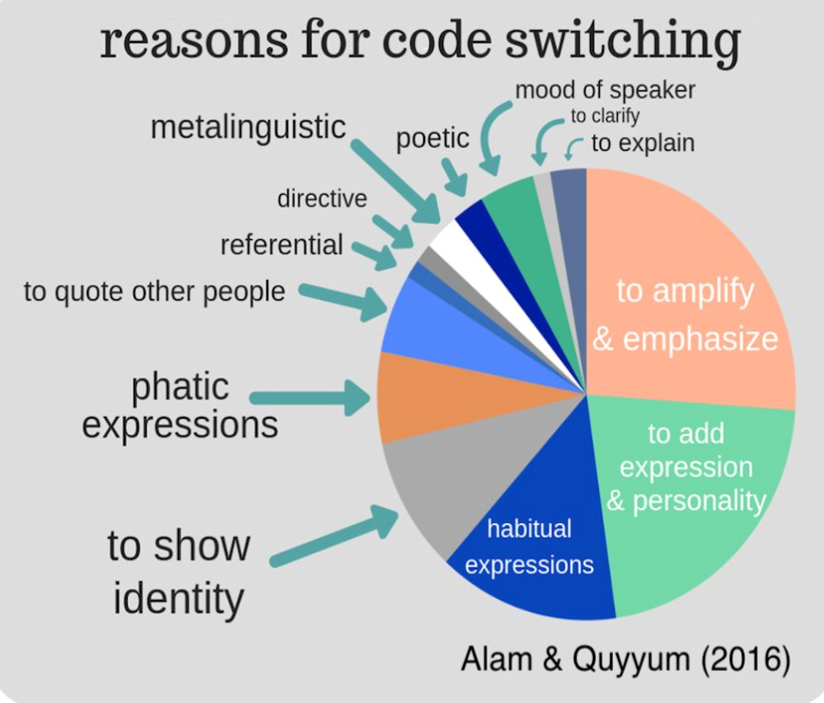

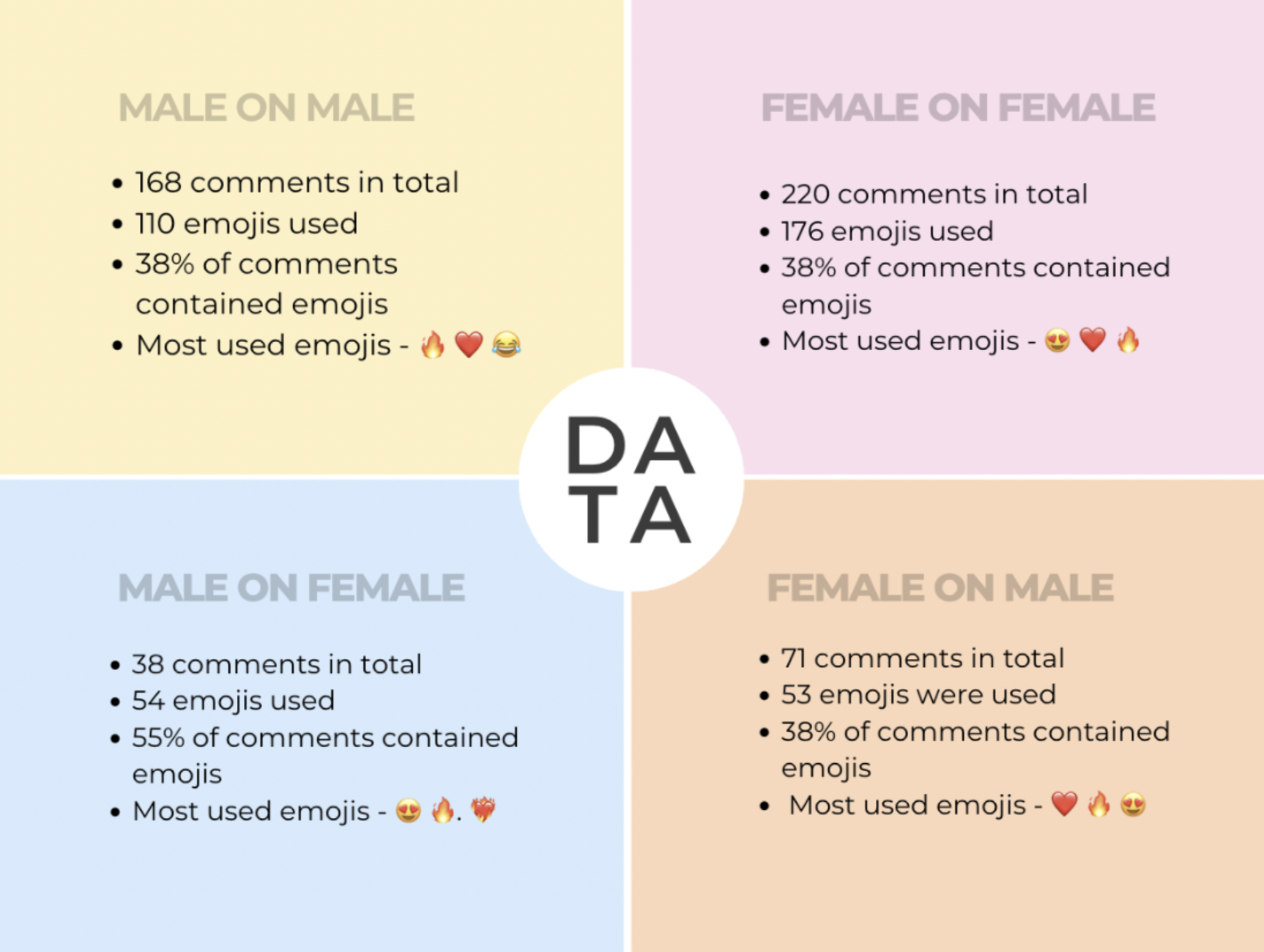

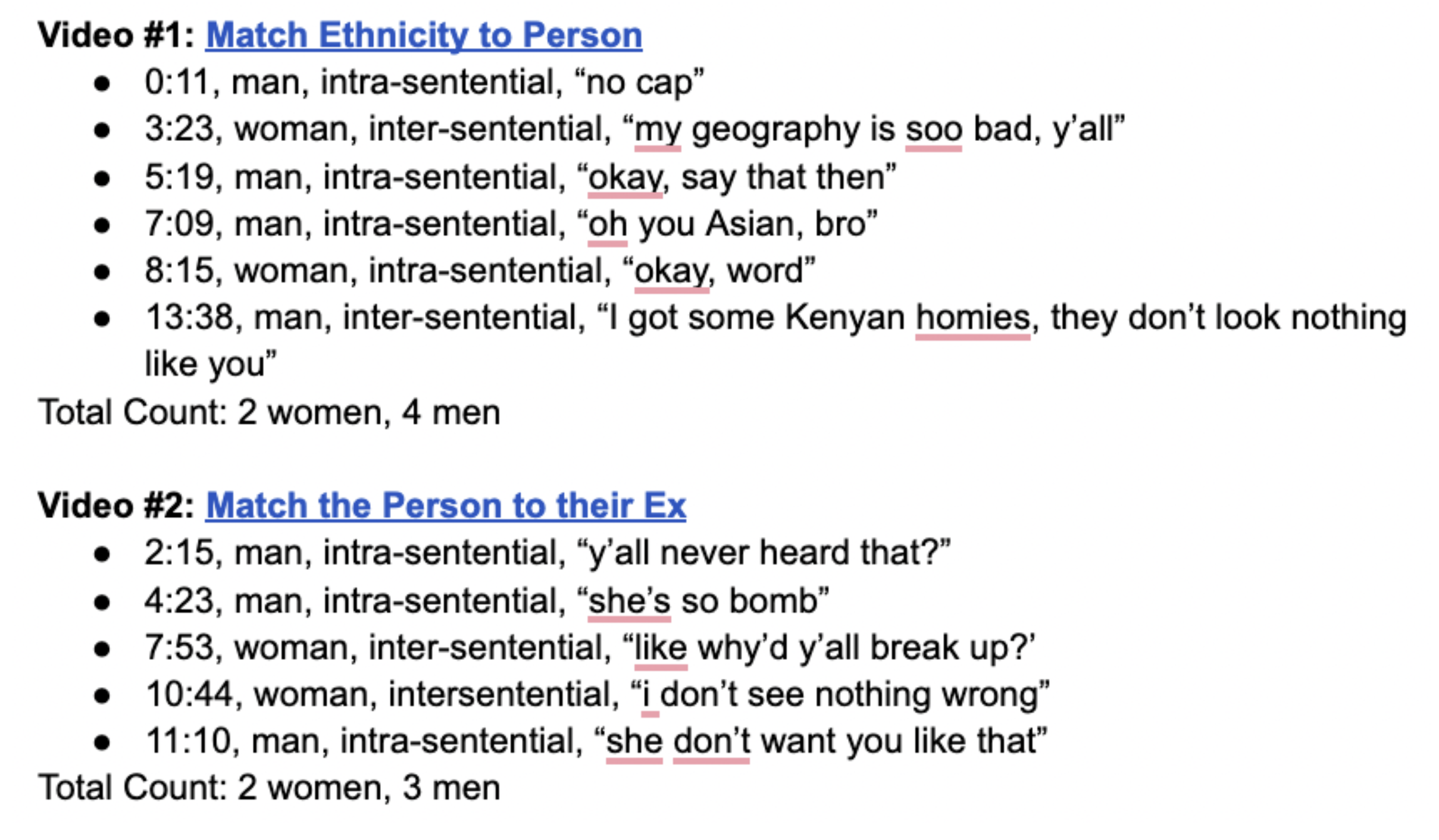

Background In recent years, TikTok has risen to unfathomable popularity, overtaking leading social media apps. While the premise of short-form content like that of TikTok is not new – its predecessor being Vine – TikTok is different in that it has the ability to reach mass audiences and create communities centered around a person and their interests. This in turn gets heavily exploited by brands eager to hand out sponsorships in an attempt to market to these communities of interest. Many of the larger “niches,” a term we define as a subculture of TikTok, establish themselves as bona fide online communities through a distinct style of content made to satisfy viewers’ expectations from creators. While this “style” of content is often related to the niche of interest, creators’ identities undeniably play a role in the reception of such content. Afterall, two creators in the same general niche may attract individuals with different preferences as a result of the linguistic differentiation. Thus, the language used by Tiktok creators is equally important in establishing a style which connects with audience members. In the world we live in, we cannot escape from media information. Constantly, we endure such things as advertisements, billboards, and TikTok notifications. The amount of words and numbers we take in every day seems to be increasing, almost violently so. Think about how Instagram creators refer to their content output as their “feed,” which we interpret literally: a stream of consciousness which their followers consume. Consequently, and subconsciously, we have to be able to “filter” what knowledge we take in, that knowledge which is concerning to us. TikTok and similar social media platforms already have a system in place to expedite this. TikTok’s “For You” page, the home page, is where the app’s analytical system gathers recommended content, based on the user’s recent viewed-content activity, to show the user. Psychologically, this is what we deem as “influencer speech.” This phenomenon of speech has been noted by many including new articles, like in one by VICE, stating that it is “the perfect balance between buoyant yet flat; it gives just enough away, without really giving anything away; it keeps me from scrolling past the video” (Hall). The visual and audio content of a video needs to be attention-grabbing in a novel way to the user, in order to not be scrolled away. If the TikTok creator cannot capture the attention of the user within the first couple of sentences, it may as well be an admission of defeat. If we look at it differently, the main property that influencer speech holds is the ability to build an image or identity in your mind that psychologically indexes for a particular niche which may or may not suit us. The duty of a TikTok influencer is to relate to audiences while also being marketable to brands for the purpose of product promotion. With the importance of strategic language in mind, we ask the question: Do TikTokers modify their speech to increase marketability? Our expected answer to this question was yes. Through observation of a collection of lexical features that we deem influencer speech, we found correlations with greater frequency of positive feedback, as well as indexation of leadership within a specific online community. Previous investigation into social media advertising has proven social media promotion to now be more effective than traditional TV commercials (Chen, et al. 2023). This finding motivated our research in proving the importance of understanding social media advertising in this social media-driven landscape we find ourselves in. Additionally, a study conducted by Munaro et al. suggests that certain lexical items can increase audience engagement and brand partnerships (Munaro, et al. 2024). Previous research has also indicated that lexical terms act as facets of one’s identity in discourse (C.M Davis. 2020). We wanted to take this research a step further to address how particular lexical features often associated with influencer speech may help or hinder one’s marketability within the volatile landscape of TikTok influencing. It was important for us to address this question in a way that would be easy for non-linguists to understand while providing flexibility, so that any conclusions we found should not be so prescriptive as to limit the individuality inherent in casual speech. We decided to look at the beauty community within TikTok for our data collection not only for its large scale – 1⁄3 of American adults use TikTok, with the majority of those users being women between the ages of 18-24, meaning the majority of TikTok users are likely beauty consumers (Bestataver 2024) – but because product promotion within this niche is highly prevalent and interwoven with the content. The content, as we will be focusing on it, will be the aforementioned lexical terms. There is a common misconception and stereotype that influencer speech, particularly within the beauty community, is vapid and meaningless. However, we reject this ideology, instead asserting that beauty influencers use particular lexical features to garner engagement and increase marketability. We call this bundle of features “influencer speech”, or “I.S.” in its abbreviated form. The features we used to define influencer speech are as follows: precision in synonyms, pronoun usage, and hyperbole. Firstly, precision is the usage of descriptive, repetitive synonyms used to build imagery for audiences that creates a psychological closeness to the product. Secondly, we examined usage of particular types of pronouns such as first-person, second-person, and inclusive pronouns (as in we and let’s) to gauge how influencers engaged with their audiences through their speech. Previous research asserts that inclusive language allows influencers to connect with and gain reputability amongst their audience (Prudencio, et al., 2023), thus inspiring us to look more closely at TikTok beauty influencers’ use of inclusive pronouns. Furthermore, in a podcast about effective persuasion, Professor Jonah Berger describes how tapping into consumer identities causes them to call to action while feeling a closeness (Jonah, 2023). Lastly, we looked at hyperbole, which we consider any speech that exaggerates a product’s quality and novelty and/or a consumer’s need for the product. We included hyperbole since research on its use within everyday speech suggests its use as ‘highly’ interactive, which emphasizes its potential power as a lexical term to connect with audiences (McCarthy & Carter, 2004). Within this category of hyperbole, we looked at phrases such as “life-changing,” “you need this product,” or influencers describing products as “the best ever.” Methods We knew it was vital to consider the context of content creators’ backgrounds, which may lead to inherently unfair comparisons. This is why the five influencers we chose are leading American makeup creators known to innovate in products and methods of application. All five have at one point or another been looked to for advice and to dictate what the next trending item or application method would be. As all of the creators are American, we can generally consider their cultural backgrounds to be similar, therefore eliminating concern surrounding cultural differences as a factor in their speech. On each video, we documented the number of views and likes garnered, then took a sample pool of 20 comments to evaluate whether the responses were mainly positive, negative, or neutral. Our evaluation process was this: comments expressing approval, excitement, or support for either the product, video, or creator are positive; comments unrelated to the topic or creator are neutral; comments expressing disapproval, disappointment, or disagreement with the video or creator are negative. We then compared these findings for each of the TikTokers to see what lexical features or variables are associated with influencers and how their presence affects the audience. Results Overall, we found that influencers generally increased their usage of second-person pronouns and synonyms across all promotional content. We also found an increase in use of inclusive pronouns, with the exception of one creator from our sample, Meredith Beauty. As for first-person pronouns and hyperbolic language, we had more inconclusive results, as usage did not shift much from promotional to non-promotional content within our sample. As seen in Figure 1.1 below, inclusive pronoun usage increased 106% in sponsored content, second-person pronouns increased 62%, and synonyms increased 141%, while first-person pronoun usage decreased slightly by 18%, and hyperbole similarly had a slight decrease by 14%. We also observed a higher number of positive comments, views, and likes within sponsored videos. Inversely, neutral and negative comments seemed to decrease with sponsored content. Figures 1.2 and 1.3 showcase our data on the quality of comments and the levels of engagement. Positive comments were shown to increase slightly by 1% in sponsored content, indicating inconclusive results due to the miniscule amount of change from sponsored to non-sponsored content. Neutral comments decreased by 16%, and negative comments decreased by 10%. As these numbers are relatively small, we cannot draw any complete conclusions from this sample. However, a large uptick in viewership of content was noted in our data, with a 106% increase for sponsored content. Additionally, likes increased by 125% in the sponsored content we observed. Overall, we found that our identified lexical features of influencer speech were used more often in promotional content, indicating a correlation between usage of influencer speech and product promotion. Discussion and Conclusion Our findings on influencer speech and promotional content on Tiktok carry various implications in real world application of marketing strategy and engagement. For instance, our findings suggest that certain lexical terms, when used strategically in social media content, can result in higher levels of engagement. We hypothesize that this higher engagement results from creators’ indexation of a leadership role in the beauty community through the use of lexical terms audiences connect to, aiding in the development of trust between creator and consumer. Our results also raise questions about the role of influencers in our society. Rather than just provide entertainment, there is immense value in their role as a talking head for product promotion. Our analysis could help us demystify the distinction between entertainer and advertiser. Future research could examine influencer speech outside of the beauty community to see if these findings are consistent across all online influencing communities and platforms, rather than the TikTok beauty community alone. Results that strayed from the overall trend of the data could correlate to numerous hypotheses. Demonstrating credibility by restraining from fallacies such as hyperboles and increased use of inclusive pronouns causes viewers to believe the review of the product is credible and therefore, increases the marketability of content. There may also be differences between personal speaking styles and brand guidelines that are required when creating sponsored content, such as promises to include certain phrases or even scripts given to influencers. We acknowledge that limitations pertaining to scope occurred throughout our research project. Due to our project’s scale, we viewed 5 different influencers with 10 videos each. All the influencers were from similar backgrounds as rich, successful, American influencers. If we had more time, we could expand our sample size to include influencers from more diverse backgrounds to see if influencer speech is still used in other cultures. This revision could determine if the trends we found are generalizable. Additionally, influencers on TikTok are able to moderate their comment section, meaning our data gathered from comment sections could be inaccurate and cherry-picked by the influencer. Finally, we did not take video length into account. However, if we had more time, analyzing video length alongside these other features could reveal patterns relating to how often features were used per second or per minute, giving an even more accurate analysis of the data. Despite these limitations, our exploration of influencer speech has revealed intriguing insights into how code-switching within influencer speech appears to aid marketability. Our thesis predicted that influencers used influencer speech more often in promotional content in order to increase marketability. After analyzing our data, we can say that this is partially true. Inclusive pronoun, second-person pronoun, and synonym usage did increase in promotional content, though our analysis of first-person pronouns and hyperbole was inconclusive. We hope that our research can serve as a catalyst for deeper inquiry into how persuasion appears in the digital world as a sociolinguistic tool. References Alajmi, N. M. (2023, August 1). The Speech of Social Media Influencers in Najd: Introducing a New Source of Sociolinguistic Data. Academy Publication. https://tpls.academypublication.com/index.php/tpls/article/view/6552. Berger, J [Social Media Examiner] (2023, March 16). The Language of Persuasion: Magic Words to Get Your Way. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6teWZLgvUso. Bestvater, Samuel. (2024, February 22). How U.S. Adults Use TikTok. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/02/22/how-u-s-adults-use-tiktok/. Chen, G., Li, Y., & Sun, Y. (2023, February 15). How youtubers make popular marketing videos? speech…Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/21582440231152227. Hall, Alice. VICE. (2023, March 29). Why does everyone on TikTok use the same weird voice?. https://www.vice.com/en/article/k7zq49/why-everyone-uses-tiktok-voice. McCarthy, Michael & Carter, Ronald. (2004). “There’s millions of them”: Hyperbole in everyday conversation. Journal of Pragmatics – J PRAGMATICS. 36. 149-184. 10.1016/S0378-2166(03)00116-4. Munaro, A. (2024, July). Does your style engage? linguistic styles of influencers and digital consumer engagement on YouTube. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563224000852. Prudencio, A. B., Sherwin, C. C., Barcelona, J. A., Niduaza, B., & Tongawan, P. F. C. (2023, July). Stylistic and discourse analysis of the language of social … IRE Journals. https://www.irejournals.com/formatedpaper/1704877.pdf.

Previous research indicates TikTok’s immense value as a tool to gather legitimate sociolinguistic data (Alajmi, 2023). We examined the speech of five top TikTok beauty influencers by first inspecting five non-sponsored videos from each respective creator to create a baseline idea of their speech when they are not advertising a product. We then compared this data against their speech when they were advertising a product or doing a review, surveying five additional videos of this kind and recording how many of our target lexical features were used and how often. The relative frequency of each lexical item was counted in terms of categorizing every video into whether it contains more hyperbolic language, precision, or pronoun usage. This in turn would allow us to gauge a shift in influencer speech when promoting products through analysis of frequencies. Ultimately, this would allow us to determine the potential most effective aspects of influencer voice when it comes to influencing audiences.