Patterns in Personality Changes Amongst Bilingual Chinese Americans

Existing literature has long since supported the idea of a perceived personality change that occurs in bilingual individuals when switching between which languages they speak in. In this study, we interviewed ten Chinese-speaking Asian American university students by asking them surface level questions related to their daily life to discern additional patterns in the demographic. Ten people were interviewed in total, once in English and once in mandarin, with a period in the two between to allow for a mental “reset.”

Ultimately, we found there to be a strong pattern of Chinese being the more concise language, with the participants being able to organize their responses in a more effective manner and taking a shorter amount of time to respond to the questions. There also exists a contrast between the formality of the two languages, but the associations are dependent on the individual, finally, we observed differences in approaches to question answering, including different thought patterns and interpretations.

Introduction and Background

Bilingualism/multilingualism is a common phenomenon globally, though the U.S. does lag behind the rest of the world in terms of that trend. Language and how we use it is deeply influenced by social forces, like interpersonal dynamics, institutional context, and cultural association. All of this leads to the intriguing phenomenon within bilingual communities of a perceived “personality change” when speaking in a different language other than their mother tongue. While previous research has documented this perceived shift in personality, especially amongst bicultural speakers, much of the literature focuses on the confirmation of this phenomenon instead of questioning the reasons behind individual manifestations of this change. What our studies do is take qualitative data from various Chinese-speaking bilinguals and record in detail the changes that occur when they are answering the same questions between English and Chinese. We analyze these results with a sociocultural lens to discover how life experiences and background can manifest in the way they unconsciously carry themselves across languages.

Literature Review

The change in personality in bilingualism is well documented phenomenon (Chen, S.X., & Bond, M.H. 2010) and one largely informed by culture, as seen in the way that is observed only in those who are exposed to the culture of both languages (Bene-Martinez et al., 2002), in other words, it is as much a result of biculturalism as it is bilingualism. People cannot perform a frame switch without having both, which is a bilingual switch between culturally rooted self-concepts depending on the language they are using (Ross et al., 2002) and is a huge contribution to what people perceive as a change in personality. As an extension of that, the language used can directly affect the emotional state of the person with the culturally informed perceptions it brings (Zhou et al., 2021), resulting in different reactions to the same thing, which is what our research design is set out to test. And finally, to add onto the differing emotional reactions that come with language, the language used in a conversation can change a person’s logical interpretation of the situation. (Li et al., 2004) find that those who learned English later in life change their way of interpreting information depending on the language used, going from categorical in English to relational in Chinese. While those who learned at an earlier age in a singular culture where both languages are used officially by their country are observed no change in logical reasoning. Ultimately, showing that the culture of a language influences the thinking process of an individual, and that is then what causes a perceived change in their personality.

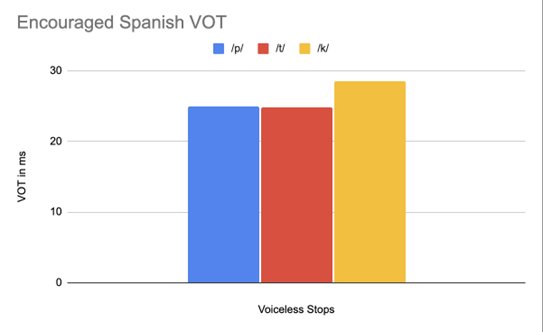

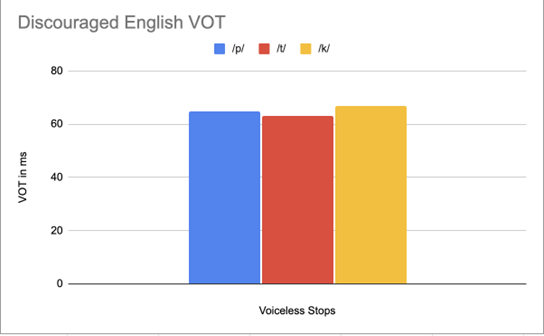

Our findings differ significantly from precious literature, as Chinese is a clear efficient language for most participants. Responses are shorter, more organized, direct, and confident. This is even true for participants who use English to communicate daily in an academic setting. On the other hand, English is perceived as a casualness, narrative and hesitation language. This informality is often accompanied by markers of uncertainty, like filter words: “um, like” etc., and more abstract or indirect wording.

Some participants stated that Chinese individuals process the ability to express emotions in formal settings such as family interaction. In contrast, influenced by educational background and social interactions primarily occurring in English-speaking environments, responses in English exhibit informality, emotional vulnerability, and lower confidence. This is mainly because for most of our participants, Chinese is typically the language of family, home and even primary identity formation. In this environment fosters directness, emotional boldness, and clarity; conversely; English is primarily the language of academic institutions, an environment that can both encourage casual peer interaction and create pressure and hesitation. Therefore, the shift in personality is less about moving from Chinese culture to American culture and more about transitioning from home self to the university self.

For example, one of the participants, Yunhan, expressed thoughtful uncertainty when saying in English: “I really want to be someone who brings value to society.” while expressing greater decisiveness and clarity when simply saying in Mandarin: “I hope to become a journalist.” Another participant also pointed out that English is emotionally causal but socially uncomfortable compared to Mandarin.

What is particularly noteworthy is our research challenges the widely held assumption that Chinese inherently promotes modesty and English promotes confidence. On the contrary, participants consistently associated Mandarin with clarity, confidence, and family comfort, while English represented education and social formality, but also elicited informal emotional expressions shaped by language insecurity and contextual associations.

Methods

Our target population is Chinese-English bilingual individuals who regularly navigate between Chinese and English language environments regardless of their perceived fluency in either language. This group includes individuals with different backgrounds and introductions to their spoken languages.

The interview asked the participants for reflection, analysis, and description of personal relationships and goals across six questions.

- What are your hobbies and interests? (你的爱好和兴趣是什么?)

- How has your week been? (你这周过得怎么样?)

- Do you like the school going to (你喜欢这所学校吗?)

- What do you like/dislike about it? (你喜欢/不喜欢它什么?)

- What do you think of your teachers this quarter? (你觉得本季度的老师怎么样?)

- How’s your academic progress so far? (到目前为止,你的学业进展如何?)

- Tell me about your career plan. (跟我说说你的职业规划吧。)

Results and Analysis

- Patterns

- Chinese is the more concise and emotionally open one, the one they use with family and friends. Not formal settings. But also, cultural association tied to it

- English: the language they use in schools and has formal associations with it depending on the person, but also cultural associations that make it feel more casual. Lack of proficiency can lead to lower confidence and less organization in speech

Table of Bilingual Interview Summary

| Interview | English Expression | Chinese Expression | Key Contrast | Relevant articles | Example quotes |

| Catherine | Causal, personality-focused, uncertain tone | Academic, confident, concise | Interpretation changes based on different languages | Li et al. (2004), Ross et al. (2002) | Eng: ‘They’re really friendly… I love them all’ Chi: ‘I feel they performed well’ |

| Yiwen | Self-disclosure, humorous, confident | Formal, calm, respectful | Switching from casual to respectful | Benet-Martínez et al. (2002), Zhou et al. (2021) | Eng: ‘8 a.m. class is a pain’ Chi: ‘I like the academic atmosphere’ |

| Jiang Jing | Reflective, hesitant, expressive | Direct, conflict, structured | Tone and clarity shift sharply by language | Chen & Bond (2010), Ross et al. (2002) | Eng: ‘I really want to bring value to society’ Chi: ‘I want to be a journalist’ |

| Zekun | Hesitant, casua l, repetitive ‘uh’ | Confident, simple, more decisive | Confidence and clarify increases in speaking Chinese | Chen & Bond (2010), Zhou et al. (2021) | Eng: ‘Uh, parking is hard… uh’ Chi: ‘Just want to make money, step by step’ |

| Tsam | Polite, indirect, academic tone | Blunt, humorous,emotionally bold | Shift in criticism and tone | Ross et al. (2002), Benet-Martínez et al. (2002) | Eng: ‘I really don’t like him… confusing’ Chi: ‘Feels worse than a dog’ |

This analysis is based on the method of bilingual interviews, thereby constituting a qualitative content analysis. We see the effects of language on the personality of Chinese American speakers in everyday conversations expressed in the conversations that are bilingual. In every study case, interviewees were more careful and polite, as well as showing their emotional restraint, when they were speaking in English. They would frequently have to stuff their speech with language fillers and monitoring, which would not be the case with them speaking Chinese since they were more confident, direct, concise, and expressive in emotions.

A case in point is Catherine’s example, where the participant felt an emotional professional distance when she spoke Chinese, due to the way she “liked the professor”. Li and colleagues (2004) captured this in their study, as they too reported that the thought processes of bilinguals vary with their languages’ usage. That testified in all that the study cases put together, the participants went frame switching and speaking individualist, casual English tones, but collective, what-respected Chinese tones in a similar manner. The discrepancy in emotional tone from calm or uncertain in English to sure or strong in Chinese matches what Zhou et al. (2021) found: bilinguals adjust their approach to emotions in accordance with what is seen as culturally appropriate in the corresponding language. Furthermore, the differences in tone and formality within a language and evaluation style of different languages (Chen & Bond, 2010) found that bilinguals do not have one single identity but instead show different characters as they switch languages.

For instance, Tsam’s case study shows the frame switching with being hesitant and polite when the participant speaks English but emotionally blunt when she speaks Chinese. It demonstrates how language shapes different national selves (Ross et al., 2002; Chen & Bond, 2010). It is also found that language cues cause changes in how bilingual and bicultural people think, feel and act that are rooted in their culture.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research team is composed of Chinese-English second language speakers who are mostly UCLA students. We learned that bilingual Chinese Americans also have a different sense of self when answering English compared to Mandarin Chinese. When they answered in Mandarin, the answers of the participants were shorter, more organized, and stronger. Their tone was more serious or formal too. When answering in English, however, people’s answers were more emotional, nervous, or unconfident. We also learned that people would be more courteous or deferential in some languages and more relaxed or blunt in others. These are not accidents, they are tied to diverse cultures, experiences, and selves that are embedded within each language. This means that language does not simply change the way we talk but also changes the way we think and feel. Our project allowed us to observe how bilinguals switch between different versions of themselves depending on context and language.

This character and expressive change reveal how much language can impact human behavior and identity. In most bilingual Chinese Americans, Mandarin speech will tie them to family, tradition, and cultural expectations, perhaps encouraging more formal or goal-directed responses. English, however, is often identified with their lives in school, in social settings, and in American society, where casual and emotional expression is more common and acceptable. These cultural associations partially explain why participants altered not only their tone but their modes of thinking according to the language. Some even reported that they “felt like a different person” when they switched languages, replicating how language can activate different cultural states of mind. By observing how bilinguals react to the same questions in both languages, we could witness exactly how malleable and dynamic identity can be. What our project illustrates is that bilingualism is not an issue of translation of words but one of constantly negotiating between two cultural worlds with two sets of expectations, emotions, and ways of presenting oneself.