Beyond the Beat: Exploring Objectification in Rap and Country Lyrics

Riley Go, Ashley Lew, Ileen Luu, Ysabella Yuquimpo

“Don’t my baby look good in them blue jeans?” Rap music has been largely criticized for its objectification of women. Yet, why has country music not gained the same reputation? Known for being family-friendly, romantic, and inoffensive, “country music is often left out of sexual media analyses as it is traditionally thought to be less harmful than other genres of music” (Lin & Rasmussen, 2018). However, 2010s studies have exposed the phenomenon of “bro country,” in which country songs have become increasingly misogynistic and centered on attractive, young women in tight clothing and casual sex (Rasmussen & Densley, 2017). Since exposure to objectifying music can lead to harmful outcomes, such as the development of body image issues and eating disorders in adolescents (Flynn, 2016), our research aims to uncover the nuanced ways in which both rap and country music objectify women and perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes, and how they may do this in different ways.

Introduction

Our focus is on the identities of male rappers and male country musicians, examining how they use lyrics to assert dominance over women and reinforce unequal power dynamics and how these patterns may change over time. Thus, our research question is: “How do the linguistic portrayals of women differ between songs by male rappers and male country musicians from the 1990s to now?”

We hypothesize that both genres contribute to the objectification, domestication, and degradation of women. While rap music is known for overtly promoting misogyny, we hypothesized that country music promotes misogyny in more covert ways (e.g. promoting female domesticity or a possessive attitude toward women).

Male rappers, often from marginalized urban areas, may objectify women and encourage a “player” lifestyle to assert dominance and reaffirm social status within their communities. Weitzer and Kubrin (2009) found that while women were portrayed as subordinate to men in most rock and country songs, rap was the most graphic in objectifying women, rarely depicting them as independent, trustworthy, or educated.

In addition, Adams and Fuller (2006) emphasize how misogynistic lyrics in rap are often at the expense of African American women, portraying them as “ not only something to be used sexually, but…also the recipient of degrading acts, disrespect, and violent behavior.” These portrayals, in turn, reinforce the American population’s negative stereotypes about African American women, and desensitizes them to the mistreatment and abuse of women as a whole (Adams & Fuller, 2006).

Male country musicians, often from rural, conservative areas, may depict women as subservient and dependent on men, to confine them within the patriarchal systems of their communities. Rasmussen and Densley (2017) examine the emergence of “bro country” in the 2010s, characterized by songs focusing on women in revealing clothing and referring to a woman using slang. Discovering that women in country songs in the 2010s were objectified more than in the past, they call attention to the negative progress toward female empowerment within the genre (Rasmussen & Densley, 2017).

Furthermore, Rogers (2013) highlights themes in country music that depict women in traditional gender roles, promote the idea that attractive women inherently have more value, and normalize coercive sexual behavior, suggesting that sexism in country music may be more dangerous when hidden within the lyrics.

Here is a YouTube video, entitled “Why Country Music Was Awful in 2013,” poking fun at the repetitive themes present in “bro country”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WySgNm8qH-I

Methods

For our methodology, we utilized Billboard’s lists of top-grossing rap and country artists, and randomly selected a subset of musicians for analysis. Afterward, we drew from Billboard to identify a top song of each artist that negatively portrayed women at least once. Covering the 1990s to now, we analyzed one top rap song and one top country song per five-year period. These songs were highly popular in their respective time periods, providing a representative snapshot of prevalent lyrical themes and content.

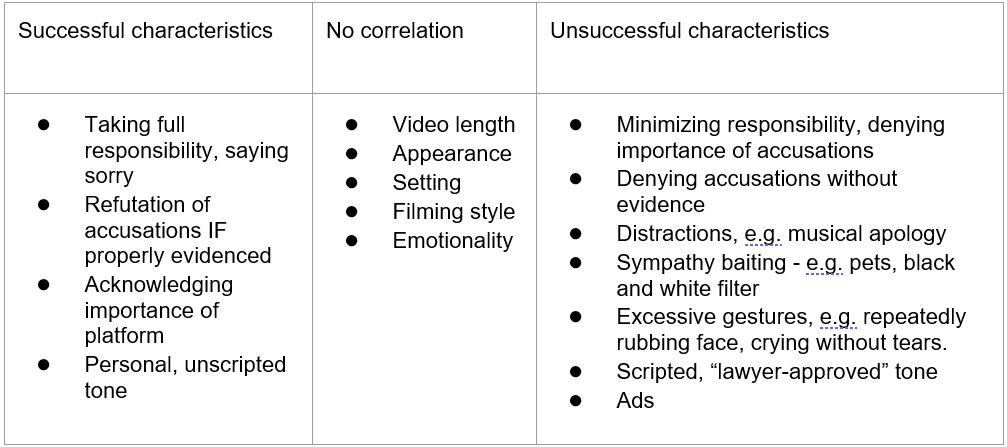

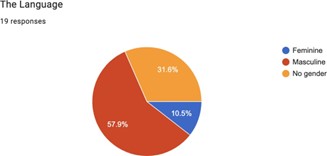

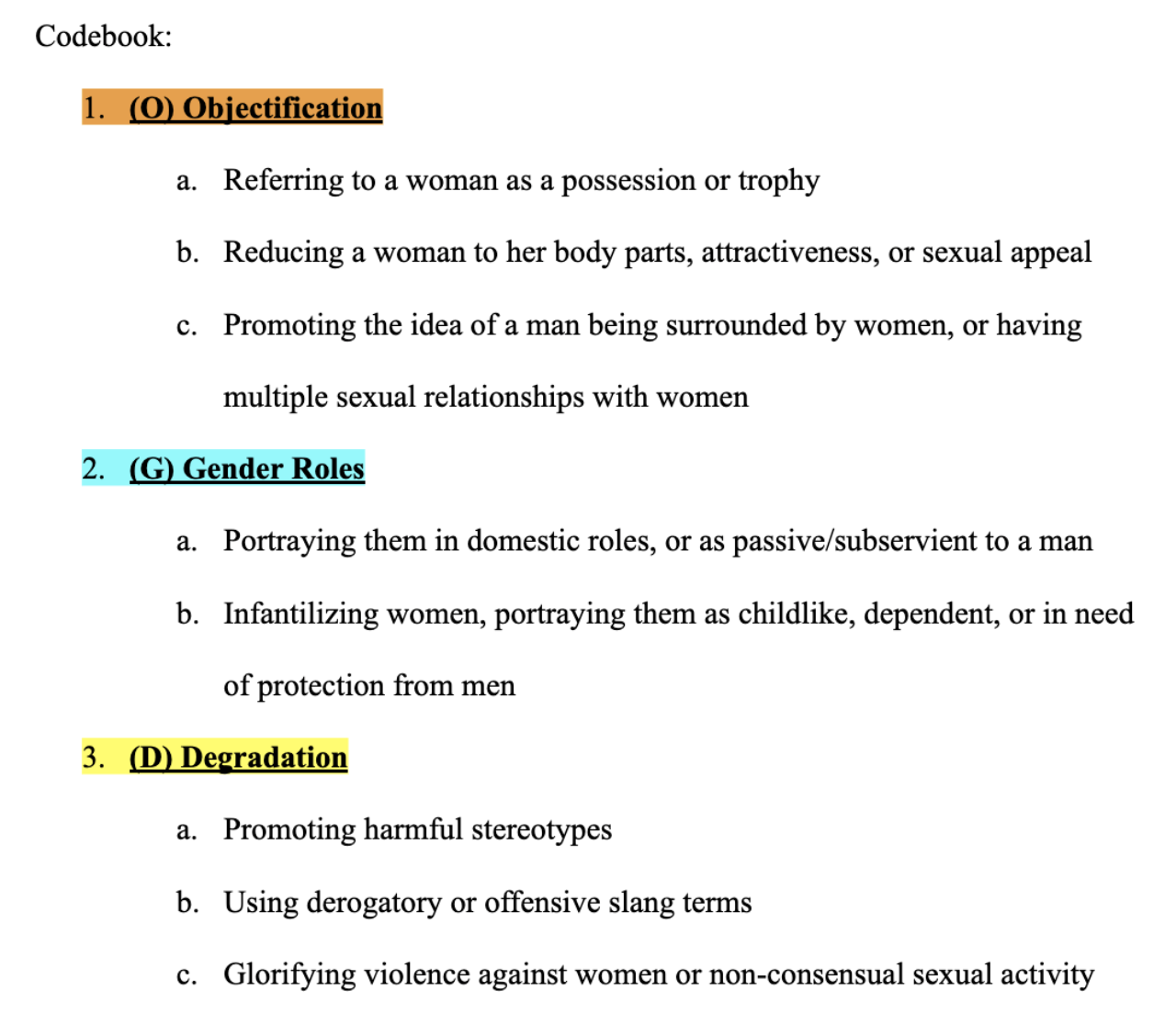

Figure 1: Our codebook, with condensed metrics from Rogers’ (2013) study. This codebook served as a comprehensive framework, enabling the operationalization of abstract concepts such as “objectification” within song lyrics.

To ensure consistency, two individuals within our research team independently analyzed each song, providing it with a rating that noted the number of unrepeated lines with instances of Objectification, Gender Roles, and Degradation. In cases of disagreement, they presented their reasoning to a third party who provided the final rating.

Results

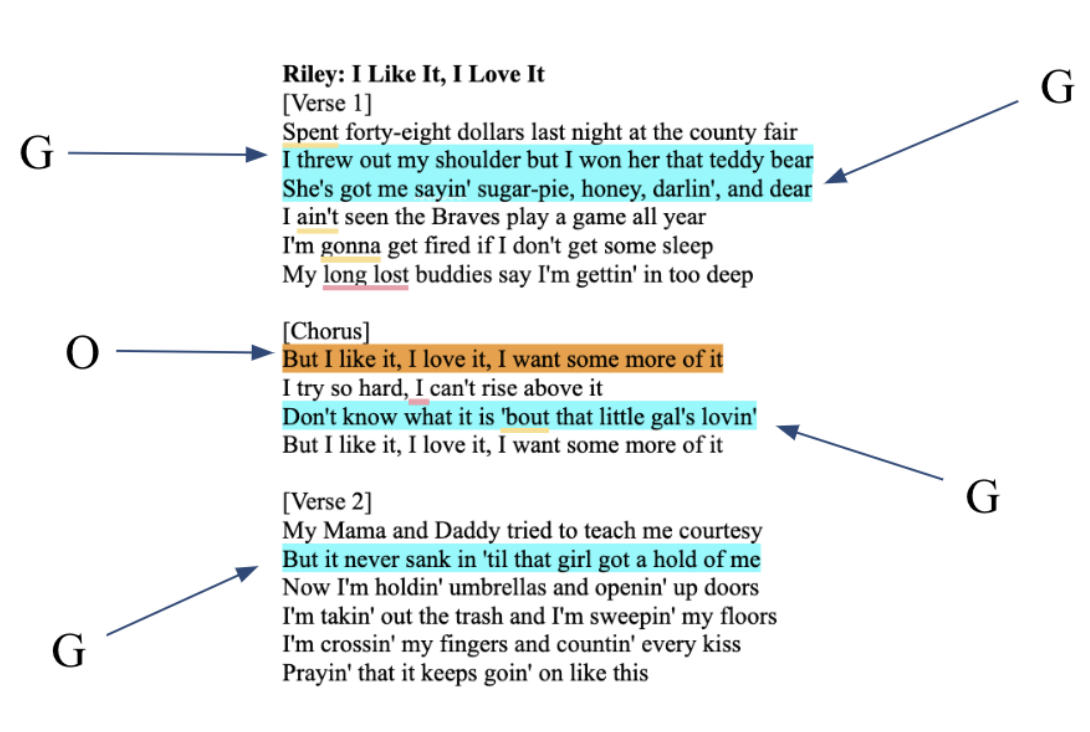

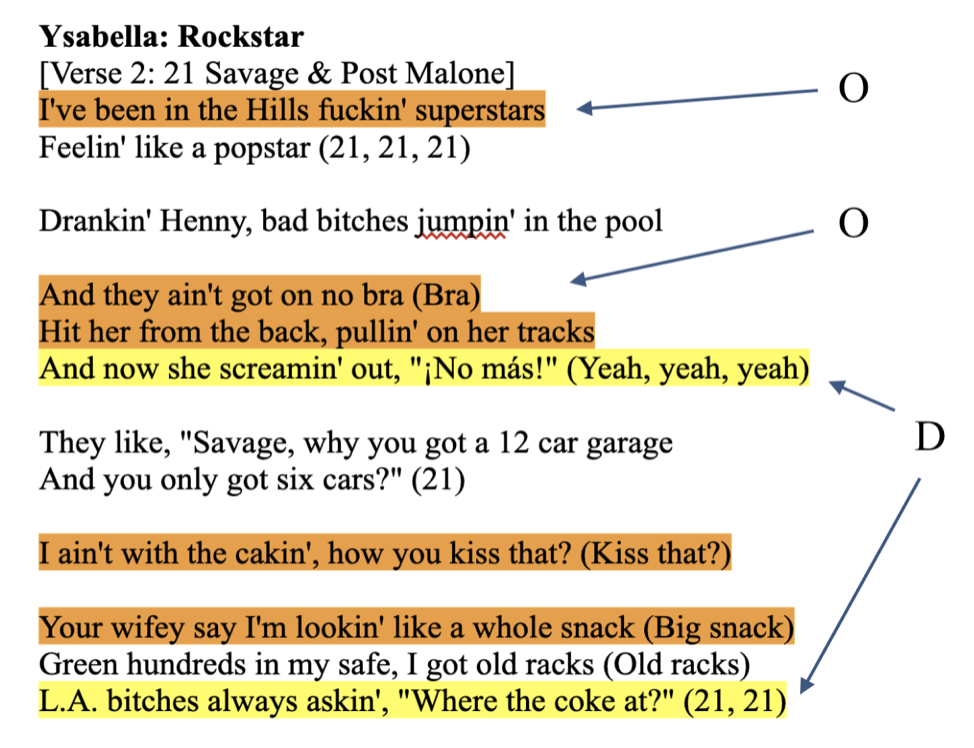

The following is an example of how instances of misogyny were identified in different songs. We noticed that in country songs, like “I Like It, I Love It”, there was a tendency for singers to use terms like “little gal” or “girl” to describe women, and this was in line with our interpretation of Gender Roles-based misogyny. We also noticed that in rap songs, like “The Real Slim Shady,” there was a tendency to call women derogatory names, or in some cases, such as in this specific song, reference violence towards women. This was in line with our interpretation of Degradation-based misogyny.

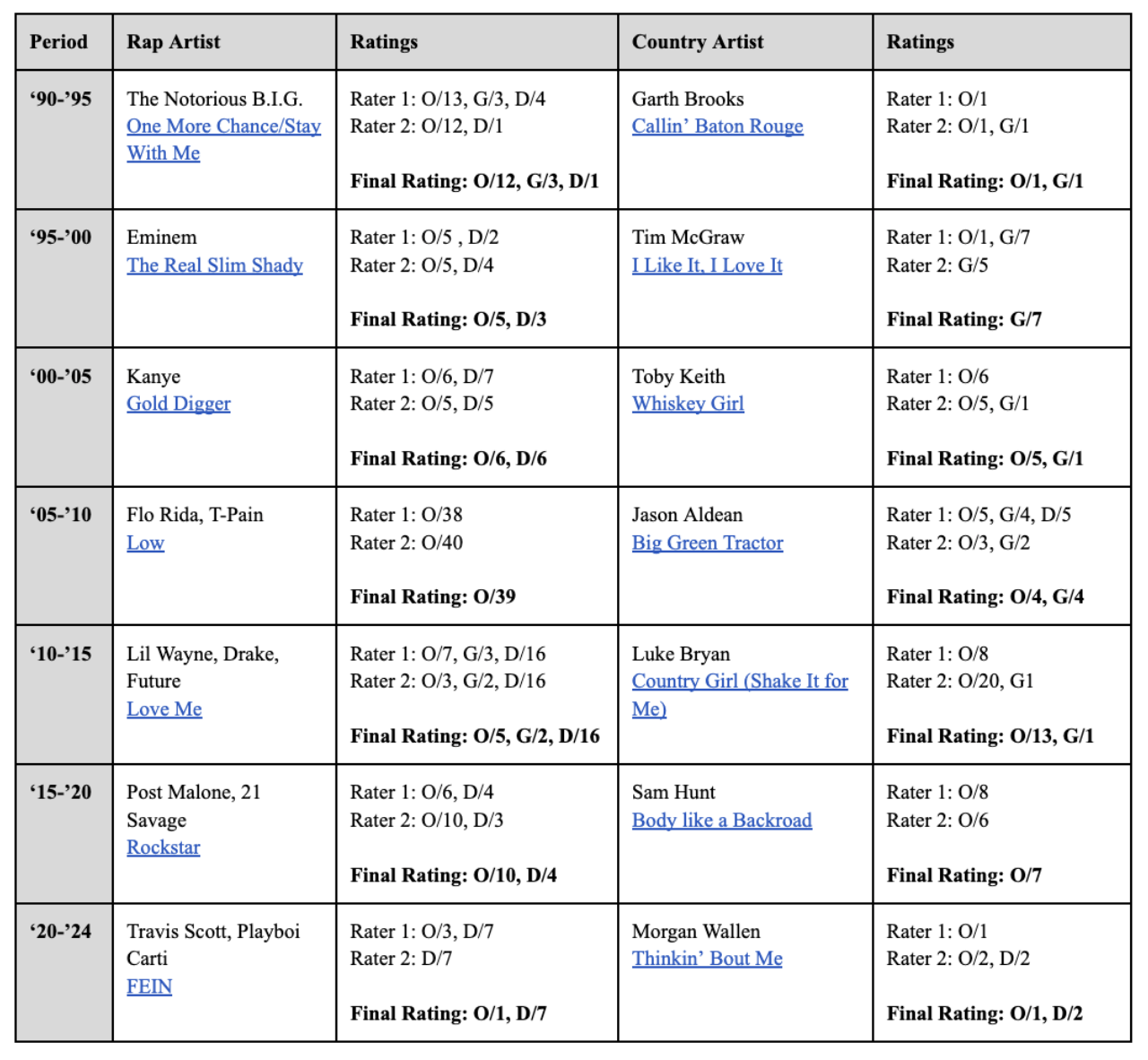

Table 1: These are our final ratings, indicating the number of unrepeated lines with instances of Objectification, Gender Roles, and Degradation. (For instance, O/12 indicates 12 instances of Objectification within the song).

Figure 2: Gender Roles and Objectification present in Tim McGraw’s country song, “I Like It, I Love It.”

Figure 3: Objectification and Degradation present in 21 Savage and Post Malone’s rap song, “Rockstar.”

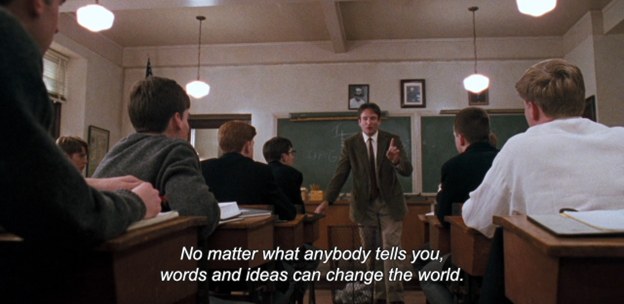

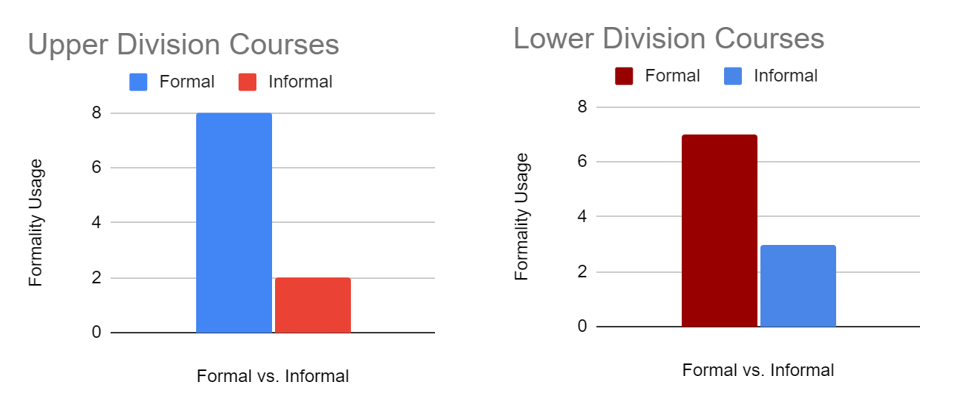

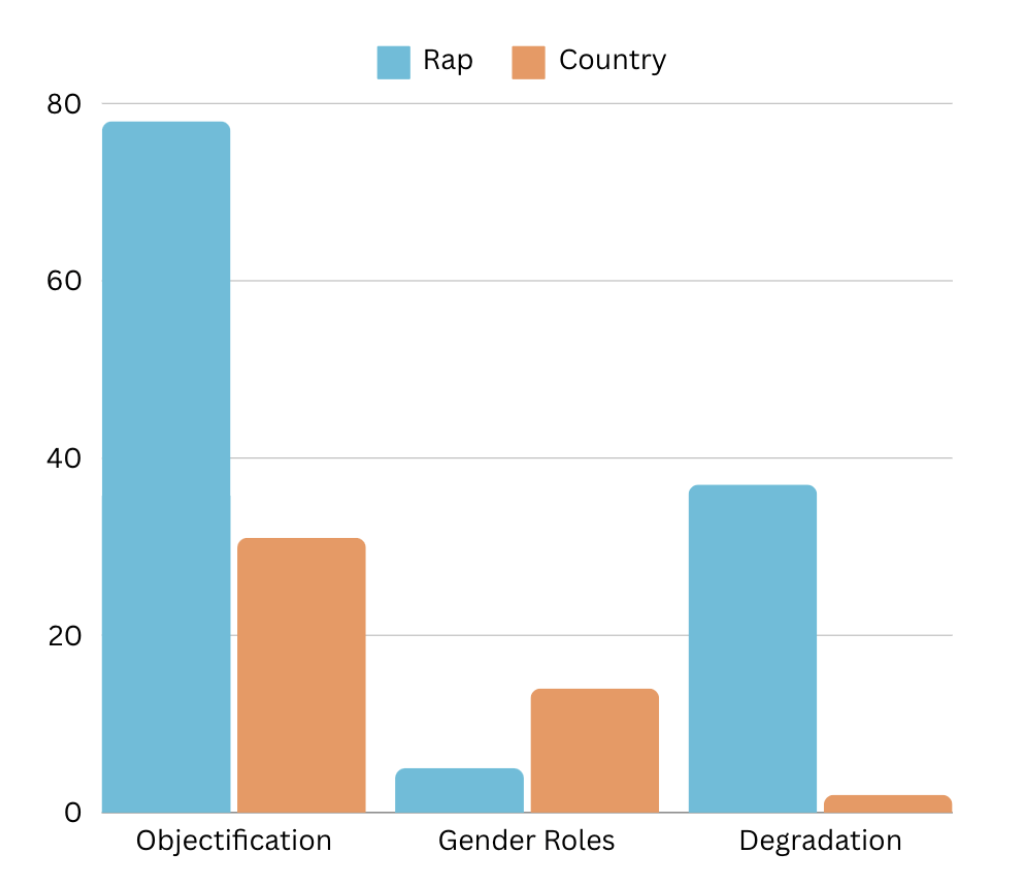

Figure 4: Bar graph, comparing the instances of Objectification, Gender Roles, and Degradation in Rap vs. Country music.

We found that rap had a total of 120 misogynistic lines, while the country had a total of 47 misogynistic lines. Objectification and Degradation-based sexism were most common in rap music, while Gender Roles-based sexism was most common in country music. This could be due to the differing attitudes towards women in rap and country music circles. Because we understand that the two genres should not be analyzed in a vacuum, their historical contexts should be considered when theorizing why they represent women in such distinctive ways.

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, rap music saw an emergence of the subgenre, gangsta rap, which focused on the hardships of growing up in the Bronx and the culture produced by that upbringing. Violence, poverty, and criminal activity are all central themes of the lyrics of gangsta rap; thus, it follows that violently misogynistic attitudes could spawn from those topics. Further, because gangsta rap is held in such high regard as a staple of the rap genre, it makes sense that modern rap artists would try to emulate the misogynistic rhetoric of the subgenre.

Country music, on the other hand, does not necessarily have as overtly misogynistic lyrics. Instead, the genre utilizes a more subtle form of misogyny that reinforces traditional, conservative gender roles. In the United States, country music is generally associated with right-wing-leaning, Southern, Judeo-Christian values. As such, many country artists conform to those values in their personal life and lyrics. It follows that country artists would portray women in ways that conform to traditional gender roles, as doing that caters to their audiences and may also reinforce what the artists themselves believe.

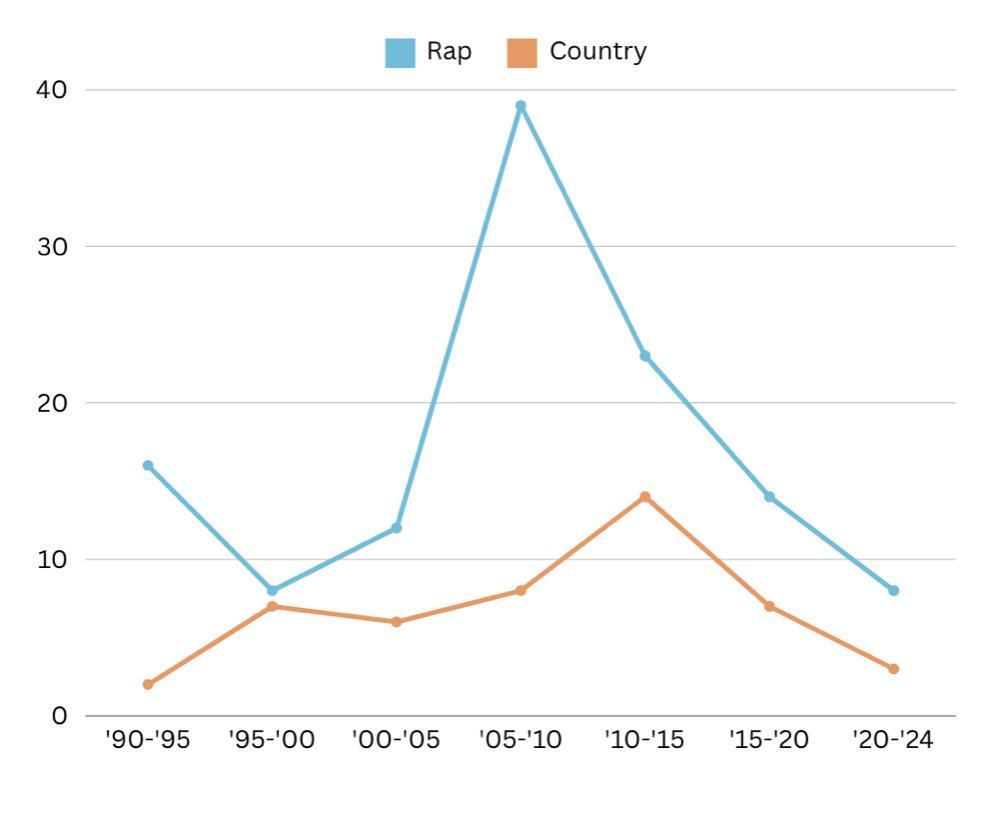

Over time, we saw a peak in misogynistic lyrics from 2005-2015, and then the numbers declined. The drop in misogynistic lyrics after 2015 is in line with the timing of the MeToo movement and other 3rd wave feminist efforts to dismantle harmful stereotypes and attitudes towards women. To stay relevant, marketable, and politically correct, male artists likely made an intentional decision to tone down the misogynistic rhetoric in songs.

Figure 5: Line graph, examining Misogyny (Objectification + Gender Roles + Degradation in total) over time in Rap vs. Country music.

Discussion

Through our song analysis, we discovered that both genres contribute to the objectification, domestication, and degradation of women. Rap music flaunts misogyny in its lyrics by calling women derogatory terms and glorifying rough, non-consensual sex and a “player” lifestyle. On the other hand, country music promotes misogyny more discreetly by infantilizing women, focusing only on their attractiveness and sexual appeal, and portraying them as subservient and dependent on men. Despite results indicating that Objectification and Degradation were higher in rap, Gender Roles exceeded in country music. Yet, these forms of misogyny are equally harmful to women, fueling both our prevalent patriarchal system and the cycle of violence against women. The impact of our analysis is solely to challenge preconceived notions about these genres and their deep-rooted association with misogyny, as well as highlight how objectifying music can both reflect and shape our reality.

While we do not want to label a music genre “problematic,” since that is harmful in itself, women are still represented as subordinate to men in rap and country, and we urge listeners and musicians to understand that the messages being conveyed fuel the cycle of female objectification.

References

Adams, T. M., & Fuller, D. B. (2006). The Words Have Changed But the Ideology Remains the Same: Misogynistic Lyrics in Rap Music. Journal of Black Studies, 36(6), 938–957. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034353

Flynn, M. A., Craig, C. M., Anderson, C. N., & Holody, K. J. (2016). Objectification in popular music lyrics: An examination of gender and genre differences. Sex Roles, 75(3–4), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0592-3

Grady Smith (2013, December 20). Why Country Music Was Awful in 2013 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WySgNm8qH-I

Lin, R., & Rasmussen, E. (2018). Why don’t we get drunk and screw? A content analysis of women, sex and alcohol in country music. Journal of Popular Music Studies, 30(3), 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2018.200006

Rasmussen, E.E., Densley, R.L. Girl in a Country Song: Gender Roles and Objectification of Women in Popular Country Music across 1990 to 2014. Sex Roles 76, 188–201 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0670-6

Rogers, A. (2013). Sexism In Unexpected Places: An Analysis of Country Music Lyrics – Office of the Vice President for Research | University of South Carolina. Sc.edu. https://sc.edu/about/offices_and_divisions/research/news_and_pubs/caravel/archive/2013/2013-caravel-sexism-in-unexpected-places.php

Weitzer, R., & Kubrin, C. E. (2009). Misogyny in Rap Music: A Content Analysis of Prevalence and Meanings. Men and Masculinities, 12(1), 3-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X08327696