Gender Portrayals in Hip-Hop Lyrics

Jazmin Flores, Charlene Juarez, Javier Nuñez-Verdugo, Sofia Nyez

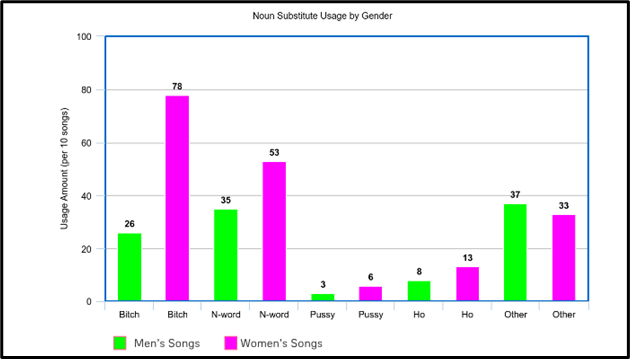

Hip-hop music as a genre has grown in popularity and oftentimes notoriety among younger generations for its catchy beats, the interesting artists behind them, and the relationships that come as a result of them, whether those be for better or for worse. Beyond its redeeming qualities, however, there has been a push in recent years especially to investigate the prominence of gendered violence in the form of lyricism. In this study, we analyzed the frequency with which certain gendered noun substitutions are found in the top hip-hop songs of 2023 written by men and women alike. With an emphasis on analyzing opposite-sex noun substitutions, our group found that women more often than not tend to refer to men in their music the most out of any other gender-to-gender category. Additionally, we found that women also tend to use the substitute “bitch” up to 3 times more than men do.

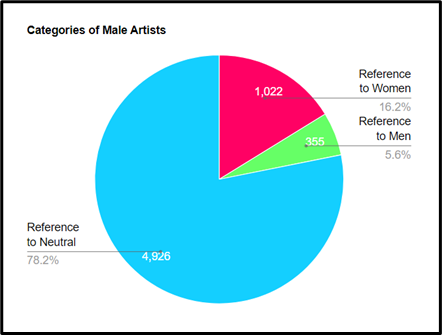

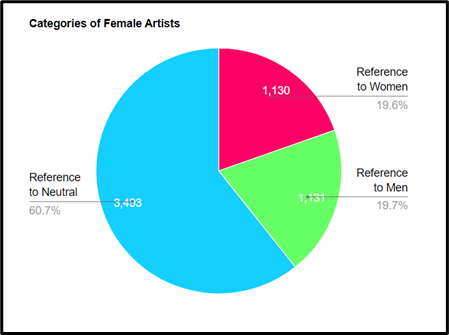

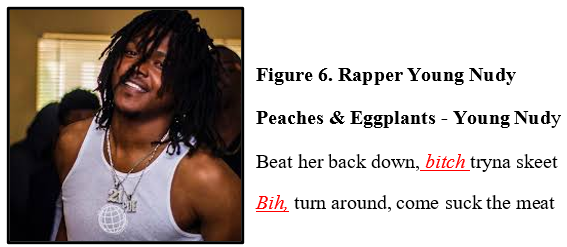

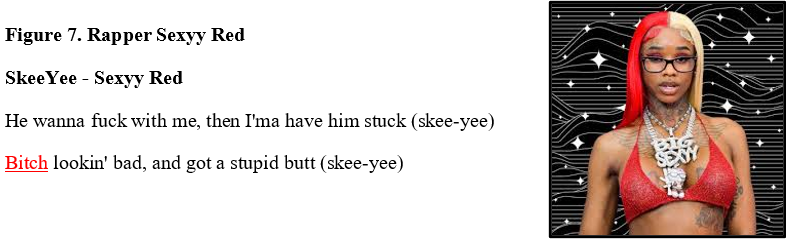

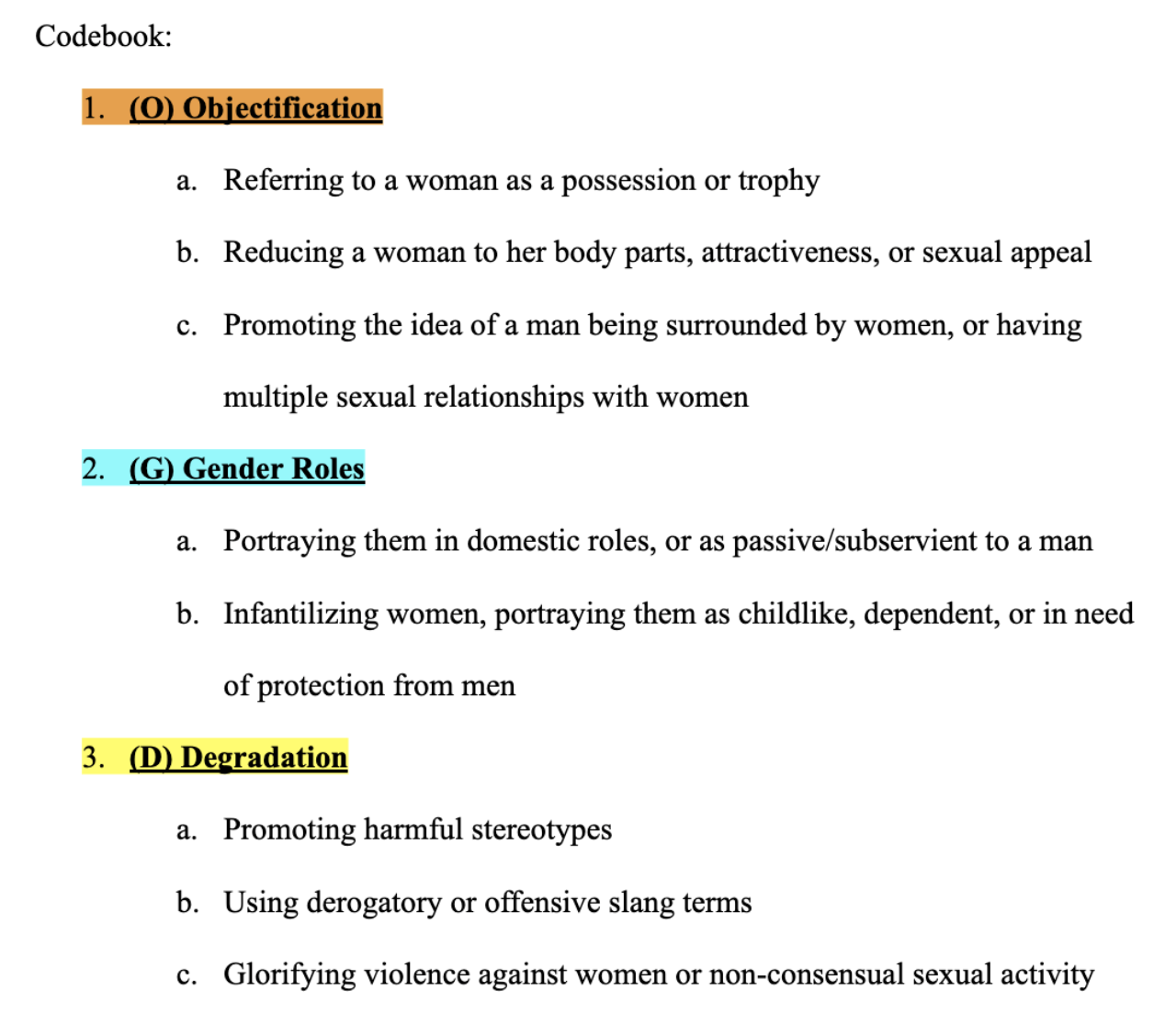

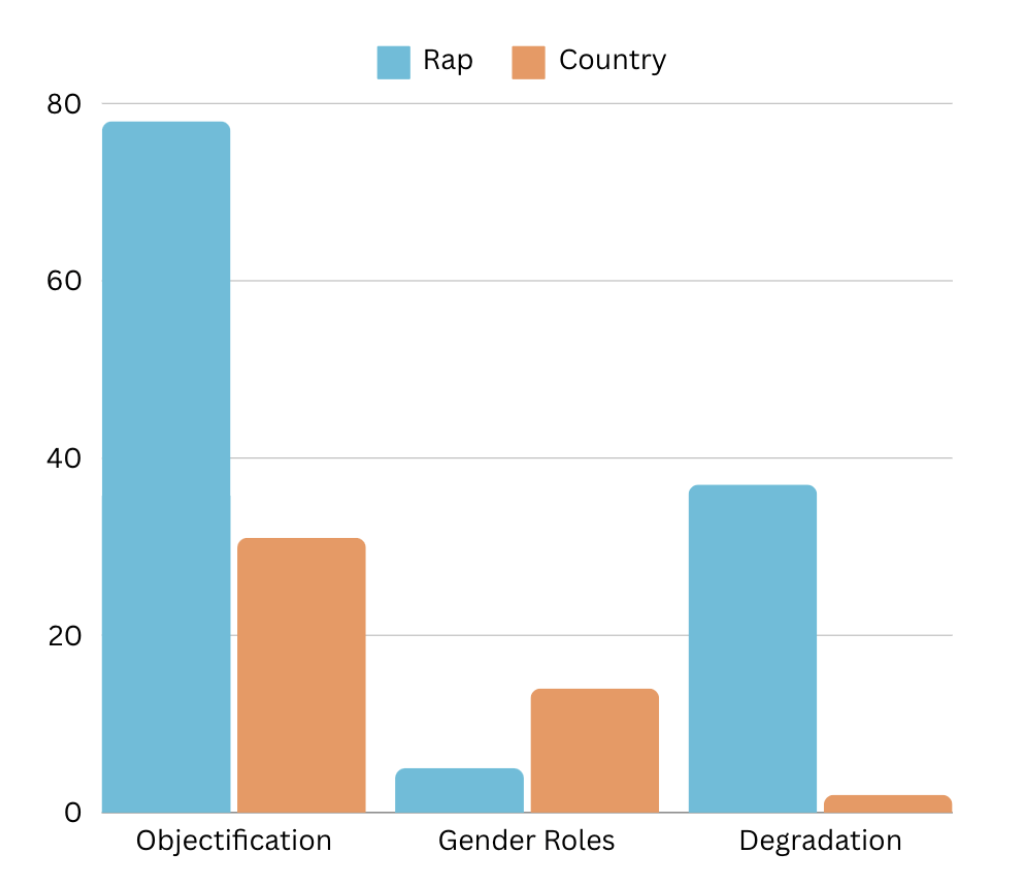

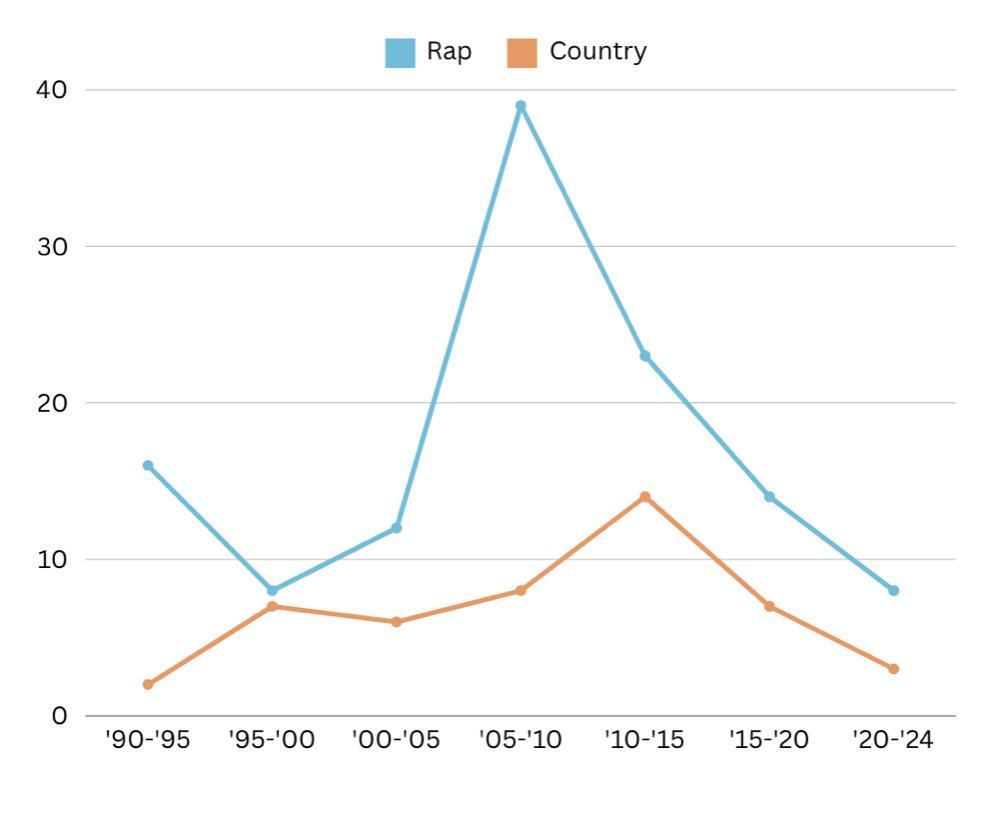

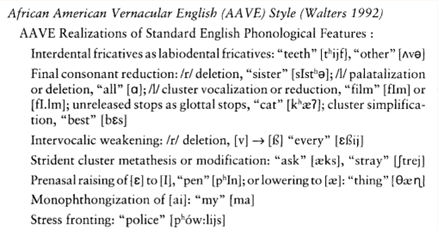

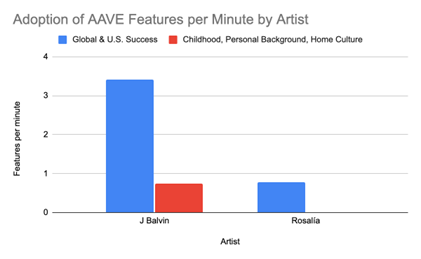

Introduction Hip-hop is a largely male-dominated industry that often finds itself as an entertaining medium/genre for promoting self-pride and rapper “beef” in the form of diss tracks towards other artists. However, the genre has also found itself to be associated with more negative ideas relating to arrogance, misogyny, hypersexuality, and drugs in the public eye. This study will focus on the issues of misogyny surrounding the hip-hop/rap industry, specifically on how women are portrayed in songs via the lyrics, to understand how these communities have contributed to creating a hostile environment for women in our society. In more recent years, there has been an uptick in female rappers who have aimed to take back their power (Krasse, 2019). Female rap artists have transformed targeted, derogatory phrases like “bitch,” “hoe,” and “slut” into forms of empowerment. Through their music and lyrics, they reclaim ownership of these words, reshaping them into symbols of strength and resilience. In doing so, they redefine societal perceptions and assert their power in the face of adversity. This study will mainly focus on the differences between how male and female rappers portray the opposite gender in their music, with a strong focus on how male rappers sexualize or objectify women and how women threaten men’s masculinity. Additionally, we will also take some time to address same-gender portrayals in the hip-hop genre using similar research strategies. We will be examining this through the lexical use and variation across the aforementioned categories. Background In recent years, there has been a glorification of this genre of music despite its content. While we are aware that misogyny is clearly present in these songs, it is interesting to analyze how it has influenced our society for better or for worse. First, we will be focusing on the language that current male and female rap artists use in their work. Music has the power to change a person’s mood or perceptions in relation to sexism (Cobb & Boettcher, 2007). Therefore, we will also comment on how the content of current male and female rap artists’ music has affected younger generations. It is important to analyze how the use of explicit language about women has affected society’s perception of them. In this study, we proposed the question: How has misogyny manifested itself in Hip-Hop/Rap music in 2023 comparatively between men and women, as demonstrated through their lyrics when addressing the same or opposite gender? Based on previously investigated data (Sallam & Shim, 2021), we expect to find that men describe women negatively at a higher rate than when they describe themselves, when women describe men, and when women describe themselves. Methodology In our study, we will be examining the descriptors of the genders (such as “wack”) and any noun substitutes (such as “hoe”). Popular artists like Gunna, Central Cee, and Travis Scott commonly use noun substitutes like “gold diggers,” ”bitches, and ”hoes” in reference to women. The use of insulting and/or derogatory language towards another on the basis of gender can be seen as a means of affirming the gender of the speaker. While the reasons behind such thoughts are nuanced, the pressing reason that we would like to highlight is gendered linguistic violence being a means of reinforcing traditional gender norms that paint men as superior to women. For a modern-day example of this, we can look no further than to the self-proclaimed “Alpha Male” influencer Andrew Tate, who was popular for a large part of 2023 for his social media content aimed at defending rather reductive and traditional views on gender (Radford, 2024). These views have the end goal of defending this idealized masculinity that celebrates male confidence and resentment towards women for apparently posing a threat to and stigmatizing such traditional gender norms. The project design will consist of identifying and gathering 20 songs from 2023 male and female rappers. We have narrowed down the song selection to the top 10 rap songs by female rappers and the top 10 rap songs by male rappers from Spotify in 2023. As we analyze the lyrics of this genre, we will look at how men describe women, women describe men, men describe men, and women describe women through the use of lexical items. Specific lexical items include adjectives, phrases, and slurs that are used as forms of derogatory remarks towards the gender that is being described. To identify our data we looked at three categories of lyrics: those addressing women, those addressing men, and those talking about anything else. As a form of methodology, we will calculate how often slurs or insulting/provoking phrases are used in regard to an individual’s gender (Sallam & Shim, 2021). Results and Analysis To quantify our data, we looked at three categories across the board through the use of pie charts; one for male artists and one for female artists to help us compare our data. In order to qualify this data, we created a histogram with the most commonly used noun substitutions to get a side-by-side view of its usage by both groups of artists. Figure 3 shows a greater tendency for men to refer to women at 3 times the rate than they do other men when just considering gender-to-gender ratios of speech. Figure 4 shows different results and serves as a contradiction to our original hypothesis, showing that women in the top songs of the 2023 hip-hop genre have almost an equal ratio to referring to other women than they do to men (19.6% vs. 19.7%, respectively). Figure 5 directly goes against our original hypothesis that men would refer to women negatively the most out of our aforementioned gendered categories. Instead, we see that, for example, women use the selected noun substitutions (excluding “Other”) in their music more than their male counterparts in each bar with at least a 50% or more increase. Conversely, both men and women almost utilize the same rate of “Other” gendered noun substitutes. Examples of these substitutes would be “Karen” towards women and “slow” as a general derogatory noun substitute. Discussion Although we originally hypothesized that male artists were to have the highest scores to their female counterparts, the findings based on the data collection were that women tend to talk about men more than men talk about men. In addition, women use profanity more often than men. Specifically, the noun substitute “bitch” is used by women 3 times more than men do, which in the early stages of our study was one of the key noun substitutions. While these findings do prove the large usage of this noun substitution, we were not anticipating it to appear under female rap artists. Relating back to the hypothesis and research question, our hypothesis was disproved, given how women speaking on men was the highest subcategory. It is important to analyze hip hop for its contributions to popular culture and therefore, the influence it has on the greater population when it specifically utilizes gendered language. Some examples were seen in the number of words that were used, for instance, in Men’s Hip-Hop Top 10: there were 6,303 words versus 5,814 words for Women’s Hip-Hop Top 10. The noun substitutions for women are a direct manifestation of misogyny in hip-hop music. In the hip-hop world, words often carry a double meaning. Is it possible that we were proven wrong? Or do the usages of “bitch,” “hoe,” and “slut” carry a double meaning? It is possible that the times we simply tally these words neglected the context of its usage in the song. In particular, there is a difference when male rap artists use certain words and when female rap artists use the same word. Let’s take a look at the importance of double meaning and context: While male artists use the noun substitution to degrade and sexualize women, female artists use it to empower women. They redefine what “bitch” means to women. By doing so, these women are taking back their power, as they no longer give men the ability to use words as weapons. Conclusion We believe it would be beneficial for future research to be conducted concerning this topic, as some limitations of this study included time constraints and a need for more expansion. One area of expansion includes analyzing music from other languages that hip-hop and rap are produced in besides English, and a possible comparative analysis between English-language music and foreign languages could be beneficial as a cross-cultural study. Furthermore, a study comparing the hip-hop of earlier decades to current music could also yield significant results, as hip-hop and rap are rapidly changing cultures owing to a number of factors, as detailed in Ellen Chamberlain’s TED Talk on the history of misogyny in the hip-hop industry. While a bit broad, it could also be interesting to look into some comparisons between other genres of music in conversation with the hip hop genre. During our presentation, we were asked if the race of the rapper had anything to do with their language use. While this is probably a factor, as we investigated during the course that every aspect of a person’s personality plays a role in the way they speak, we chose to focus on the gender of the artists instead. This is because many of the artists in the hip hop industry are African American, and thus, it would be difficult to distinguish between marks of the group or marks of the music industry. We also did not want to perpetuate the stereotype of the “violent black man” or “angry black woman” through our research and decided to stick to only the gender differences. Though, it should be noted that there are definitely more factors at play in the language use of hip-hop artists besides their gender, and it could be beneficial to study more into that topic using careful consideration. We believe that this study can fit into the larger body of research surrounding misogyny in the hip-hop industry as displayed through linguistic elements. Though the results aren’t exactly exemplary of what has been previously displayed in the literature, we believe it opens the floor for more discussion about not just the prevalence of discrimination but the forms in which it might come. While much literature believes women to be the target of discrimination from men for the most part, our research found that women not only speak about men at a higher frequency but use derogatory terms more often as well. All in all, while progress has been made in addressing misogyny within hip-hop, rap music, and artists, there is still much work to be done. By understanding the nuances of gender representation in lyrics and challenging harmful stereotypes, the industry can move towards a more inclusive and unprejudiced community for future artists and listeners. References Boettcher, W. A., & Cobb M. D. (2007). Ambivalent Sexism and Misogynistic Rap Music: Does Exposure to Eminem Increase Sexism?. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00292.x. Chery, C. (2024). RapCaviar Presents: Best Hip-Hop Songs of 2023. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/playlist/37i9dQZF1DWZFV9Asvj1J9?si=PdIXfalHQs-tcMM0hRggZg&pi=u-Abilm4LaTuW5&preview=coverart. de Leon, A. (2007, June 6). The complex intersection of gender and hip-hop. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2007/06/06/10783904/the-complex-intersection-of-gender-and-hip-hop. Krasse, L. (2019, Spring). A Corpus Linguistic Study of the Female Role in Popular Music Lyrics. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1481063/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Neff, S. (2014, May 24). Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison. Undergraduate Thesis Western Michigan University. Pp. 38. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3486&context=honors_theses. Prior, J. (2017, March 1). Teachers, what is gendered language?. British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/what-is-gendered-language. Radford, A. (2024, March 12). Who is Andrew Tate? The self-proclaimed misogynist influencer. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-64125045. Sallam, A. M., & Shim, J. Y. (2021, February). Gender-biased English language in hip hop music. ARC Publications. https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v9-i2/1.pdf. Wayne University. (2019). Misogyny in Hip Hop. TED. Retrieved June 12, 2024, from https://www.ted.com/talks/ellen_chamberlain_misogyny_in_hip_hop.