“Speaking of women’s comedy…”: An Analysis of Linguistic Traits by Male and Female Standup Comedians

Samuel Alsup, Eden Moyal, Jinwen (Wiwi) Shi, Yitian (Riley) Shi

The question of whether women can be funny is long outdated and has, thankfully, been answered in the affirmative. This project investigates how funny people – namely, stand-up comedians – perform (or don’t perform) their womanhood in speech. Studies conducted by 20th-century scholars highlighted multiple facets of language that are characteristic of women’s conversation, such as tag questions, hedges, and excessively specific use of color terms. This study attempts to answer the question: do 20th-century conclusions regarding “women’s language” in conversation hold up in the context of contemporary stand-up comedy (Lakoff 1998)? Transcriptions of live stand-up acts by White North American men and women indicated that certain features associated with women are indeed more salient in women’s standup, while others seem to be equally used by men and women. This points to a decreased divide over recent decades in what is traditionally seen as acceptable ways of being a man or a woman, and a trend toward accepting the vast spectra of gender identity and gender performance.

Introduction and Background

Research into “women’s language” in the 1970s and 1980s pointed to proposed differences in speech between men and women (Men, women and language — a story of human speech), including certain features of conversational speech that are more salient among, and characteristic of, women. Researchers such as Lakoff (1998), Tannen (1990), and Cameron (1997) codified these differences, noting the response to a society that taught women to be polite and therefore unimposing. A few of the features of “women’s language” include hedging, tag questions, and filler words. On the other hand, men use more expletives and are more likely to drop the “g” sound at the end of a word (Bailey and Timm, 1976, cited in Guvendir 2015; Fischer 1958).

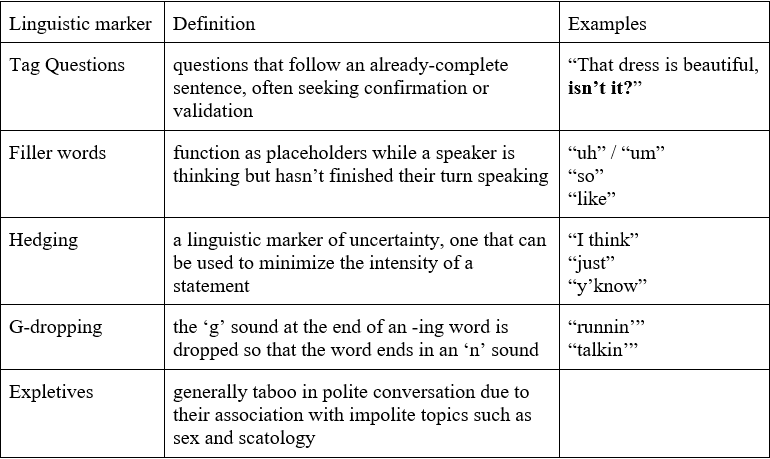

We examined the following phenomena: tag questions, filler words, hedging, g-dropping, and expletives. Definitions and examples of each can be found in the below table.

Since these observations were made last century, we examined whether they would hold up in contemporary times. In recent years, society has witnessed a trend of greater gender equality, including breaking down traditional gender expectations (Solbes-Canales, Valverde-Montesino, & Herranz-Hernández, 2020). Therefore, it occurred to us that it might be necessary to re-examine gender-associated language. If men and women are slowly creeping closer to each other in fields like business, sports, politics, and more, could language be among those fields as well?

Our initial hypothesis was that established linguistic gender differences would hold up over time, since we expected that linguistic norms shift more slowly than political trends and social issues.

We looked at stand-up comedy in particular for a number of reasons:

- Stand-up is one of those historically-male careers, where women are considered the outlier. With women making inroads in this field, we thought to examine if language has shifted also.

- Comedy, like gender and language, is a performance. Because comedy is explicit in its performance, it allows for sensitive topics to come to light in a humorous, non-threatening way.

- Stand-up comedy is a version of communication in which the speaker does not end their turn or wait for a response. Because there is no verbal interaction from the audience for both men and women, we can surmise that the playing field is relatively level and the only changing factor would be the comedian’s performance.

Methods

We theorize that when speaking about gender, it seems likely that the speaker would indicate a particular stance, either in solidarity with or opposition to the demographic they’re talking about. A total of ten White, North American comedians were analyzed, each in the context of stand-up comedy. We examined sets/parts of sets where the comedian was speaking on the topic of gender or feminism, for a total of eleven minutes (639 seconds) for all comics combined. We counted instances of tag questions, filler words and phrases, hedging, g-dropping, and expletives.

To help minimize variability, we ensured that the data was from stand-up comedy performances from the past five years. We noted each time that each linguistic feature was used in each act and kept a tally per comedian. We also recorded a general topic for each clip, so as to give slightly more specific context as to the content of the act. We then quantitatively analyzed the number of various gender-associated markers that were used in the clips, which ranged from thirty seconds to two minutes, using an average use of each feature per gender alongside the totals of each performer. We compared the five masculine-presenting comedians to the five feminine-presenting comedians to see if either of the genders we examined fit the conclusions discussed in the existing literature. In order to make sure that longer clips wouldn’t hold more weight, we set our evaluation to a per-30-second rate.

Results & Analysis

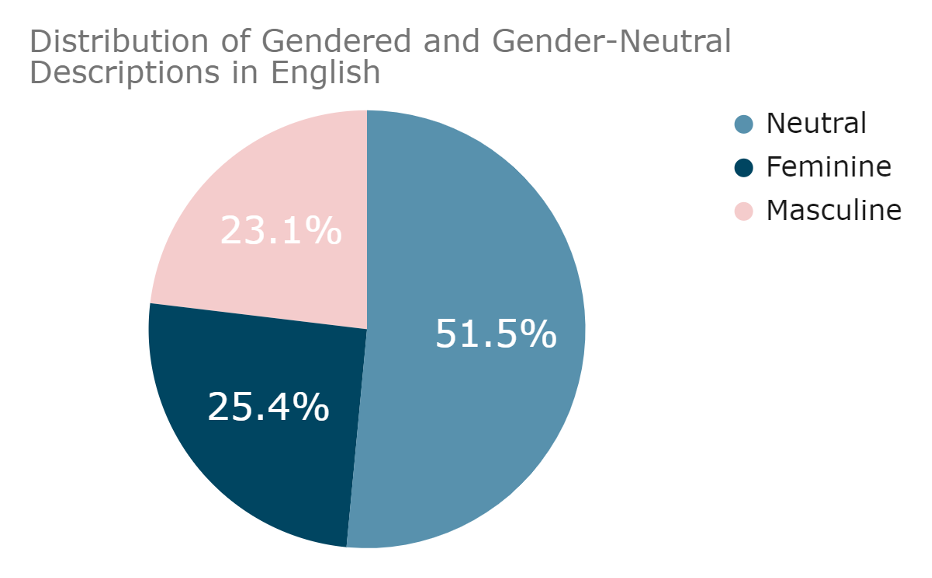

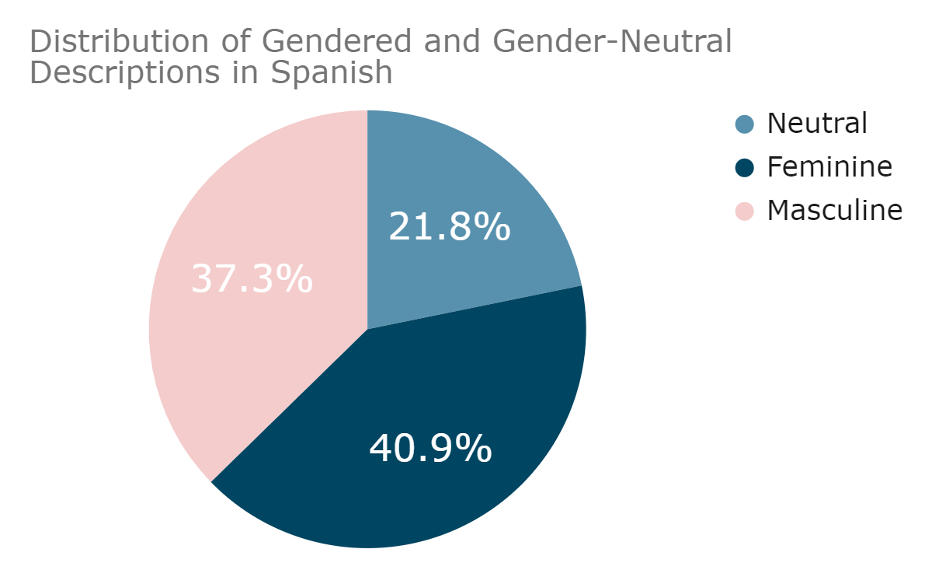

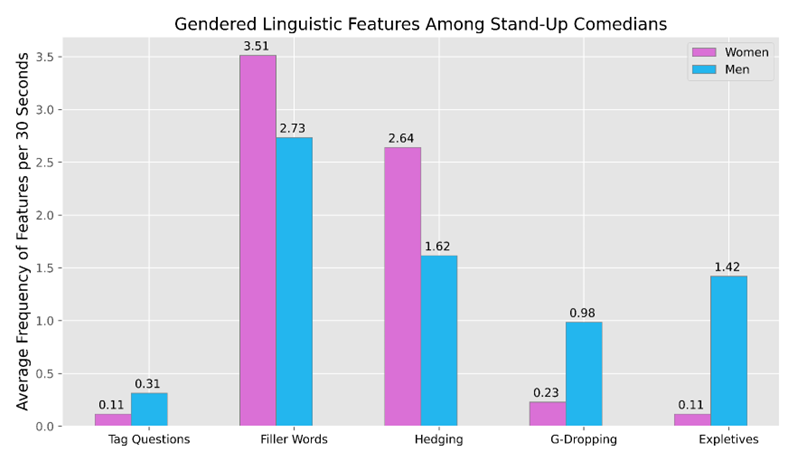

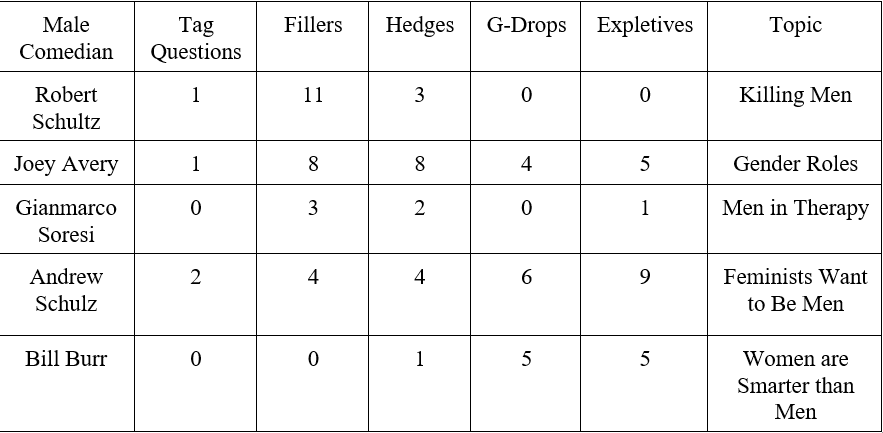

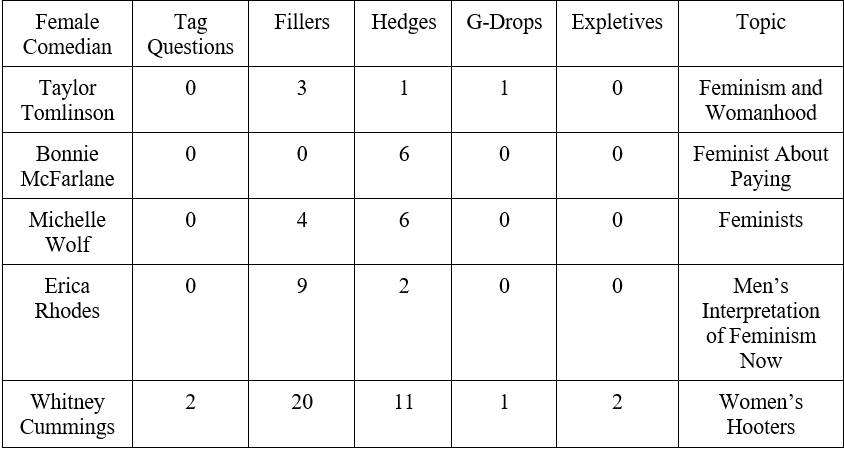

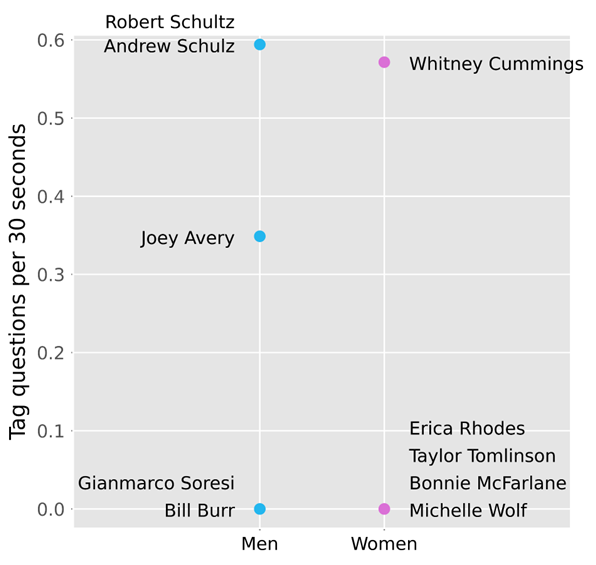

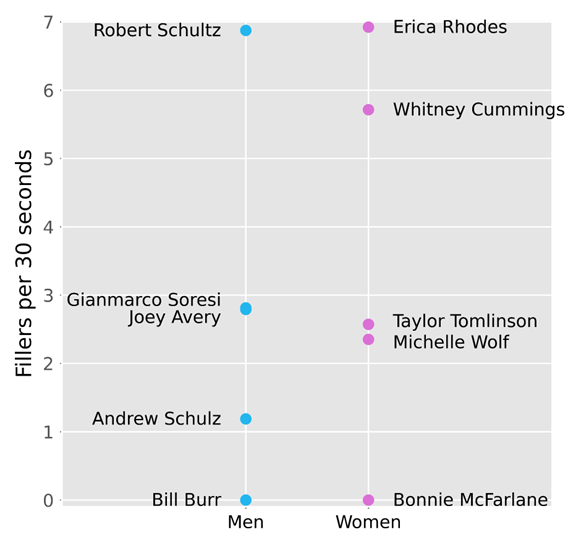

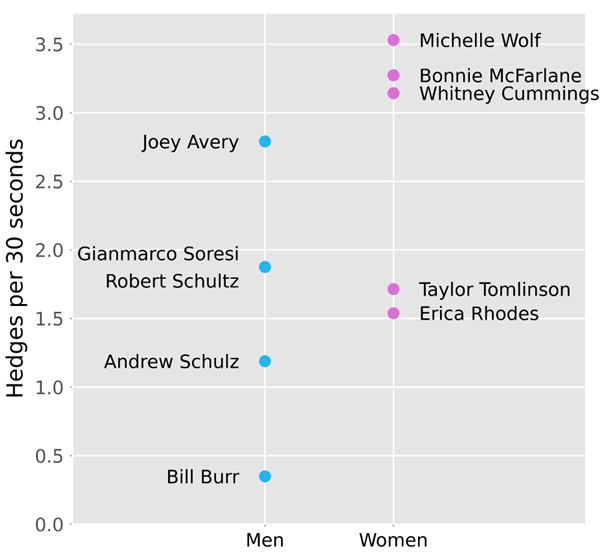

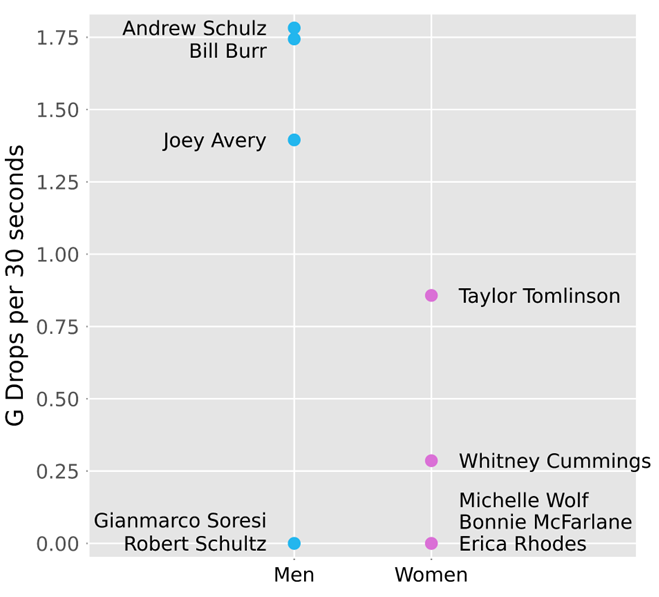

We found that the average usage of the relevant linguistic features per 30 seconds for males in our data set was: 0.31 tag questions, 2.73 filler words, 1.62 hedges, 0.98 g-drops, and 1.42 expletives. In contrast, the average usage per 30 seconds for females was: 0.11 tag questions, 3.51 filler words, 2.64 hedges, 0.23 g-drops, and 0.11 expletives. The figures below show a comparison between male and female comedians for the linguistic features mentioned.

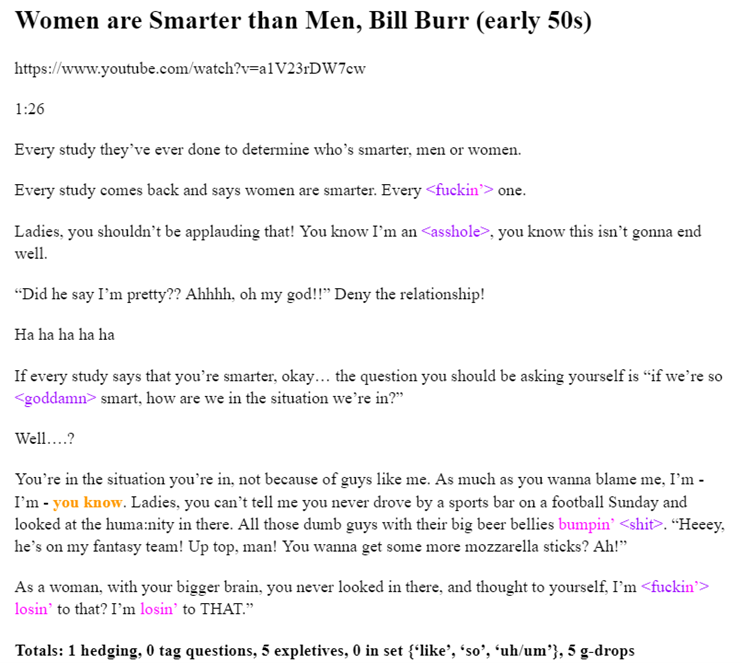

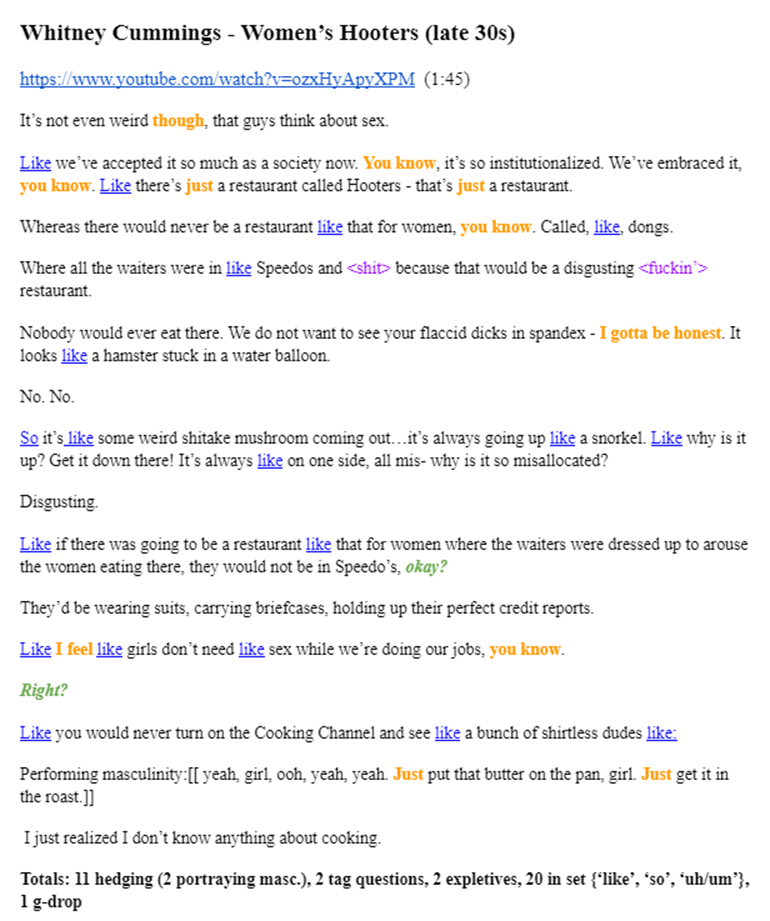

Our most “classic” exemplifiers of masculine and feminine speech were Bill Burr and Whitney Cummings, respectively. Bill Burr used many expletives and g-drops, and very few hedges and fillers. In contrast, Whitney Cummings used many hedges and fillers, and very few g-drops and expletives. We will relate each linguistic feature to them for context but note that they are the extreme ends of the spectrum. Transcripts from each comic’s set, as well as our summarized dataset, can be found below.

First, we found that there wasn’t a big difference in the usage of tag questions between male and female comedians. Tag questions weren’t used very frequently regardless of gender; less than one time per minute on average, with half of our comedians not using any at all.

Bill Burr didn’t use any tag questions, while Whitney Cummings utilized tag questions twice. This difference does not appear significant across the rest of our comedians.

We saw that our female comedians used fillers more often than their male counterparts, by about one or two every 30 seconds. The graph below does show one male outlier, who was one of the younger men on stage. This will be touched on in the discussion.

Bill Burr didn’t use any fillers, whereas Whitney Cummings used an average of six filler words per thirty seconds. However, the results were more marginal over the full dataset, with an average difference of just one filler per minute between men and women.

Our female comedians tended to hedge at least once more per 30 seconds than our male comedians. The figure below shows that three out of five female comedians hedged more than the top-hedging male.

Bill Burr accordingly hedged one time, whereas Whitney Cummings utilized hedging eleven times in a similar timeframe. While there appears to be a correlation between hedging and feminine speech in our dataset, it’s not conclusive according to our statistical analysis.

G-dropping results appeared to be much more correlated to gender than any previous linguistic feature we measured: the average female used it four times less than the average male comedian. While three female comedians and two male comedians didn’t use any g-dropping, among those who used it, the men did so much more frequently, as seen in the graph below.

Bill Burr and Whitney Cumming utilized g-dropping five times and one time, respectively. Though there appeared to be a correlation, with a 124% difference between the average usage of g-dropping between males and females, there wasn’t statistical significance in our small dataset.

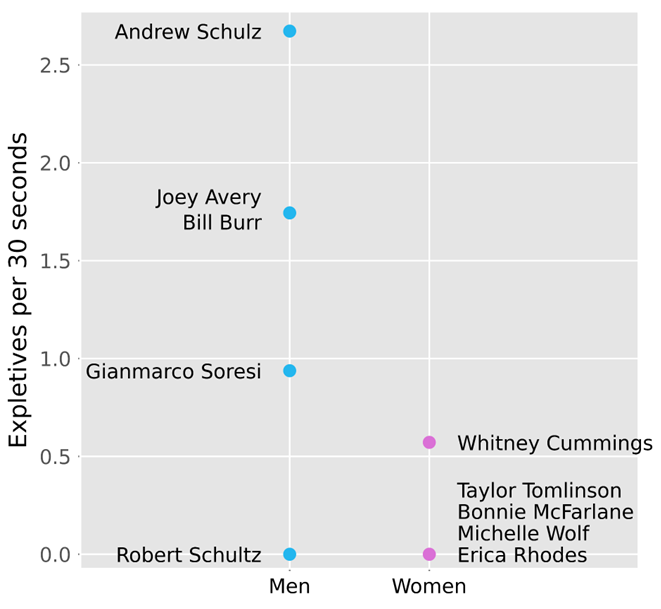

One linguistic feature that proved to have statistical significance was the usage of expletives. Four out of five female comedians didn’t use expletives at all, while only one male comedian didn’t use them. The males that used them did so at a rate ranging from two per minute to more than five per minute, as seen in the graph below.

Bill Burr used expletives five times compared to Whitney Cummings’ two uses. Interestingly enough, Whitney Cummings was the only female comedian who used any expletives at all, even though she tended to (otherwise) stick to what previous research deemed feminine speech.

Overall, the biggest differences between males and females in our data are in hedging (47.9%), which was slightly more common in females, g-drops (124.0%), and expletives (171.2%), which were both more common in males. Tag questions were rarely used by any of the comedians, so even the 95% differential between the sexes is statistically meaningless. Filler phrases had a slight correlation with being more common in feminine speech, but not a very significant one (25.0% differential).

Discussion

An overall examination of the results of our data shows several things.

First, some linguistic features thought to be more characteristic of women have indeed held up in a stand-up context as well as over several decades. For example, we saw that women did indeed hedge more frequently, and used much fewer expletives and g-drops than men on stage. It’s important to note that the difference between men and women for hedging wasn’t large enough to be significant. However, we can say that there might be some correlation between gender and frequency of hedge use. The results were similar for g-dropping and fillers, as they both appeared to have a correlation in our data, however, not enough to be statistically significant. As an example, female comic Taylor Tomlinson hedged twice with one g-drop and three fillers in a 35-second clip, while male comic Gianmarco Soresi hedged twice as well, with no g-drops and three fillers, in a 32-second clip. This comparison shows very little difference between them, pointing to placement somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of gender performance.

For expletive use, though, the difference between men and women was statistically significant – that is, large enough to make generalizations. This conclusion does stem from research showing that men are more casual in conversation than women, allowing for less formal speech.

However, plenty of linguistic features thought to be more characteristic of men or women in the past don’t hold up as well anymore. This could be due to simply the passage of time, the shift to allowing for more fluid gender identities in contemporary times, or potentially because of standup being a different kind of linguistic environment in that it is non-conversational. While we expected to find a more significant gap between men and women in their use of linguistic features, in reality, speech was a lot more ambiguous and closer rather than disparate.

We can look at the use of filler words for an example of this ambiguity. Though there can be exemplified differences between male and female performance, such as what we see between Whitney Cummings and Bill Burr, in today’s age it is much less common to exert these drastically different performances. Instead, we see more use of fillers somewhere in the middle of the spectrum, with most comedians closer to the center than to either traditionally gendered pattern. Thus, we end up with our dataset showing a very marginal difference.

Some other observations that we made revolved around the differences within the group of male comedians. The two male comedians who displayed the most classically ‘male’ use of the features we examined were the two oldest, being born in the 1980s or earlier. The younger ones, born in the early 1990s or later, were much more likely to use features traditionally associated with women. That is, younger men were more comfortable using hedges and filler words especially. This observation might indicate that younger men are becoming more comfortable with performing certain aspects of femininity, which reflects a greater trend in playing with gender in the last few years. Alternatively, it could reflect the increasing acceptance of traditionally female features of speech – its dissociation from femininity and increased generality.

Conclusion

An analysis of contemporary stand-up comics for features of speech marked feminine or masculine showed that conclusions made in 20th-century literature no longer hold up. Features that were characteristic of ‘women’s language’ in 1990 are, thirty years later, more general and practiced by male speakers as well as females – especially by younger men who grew up in less rigid society than their older counterparts. This difference between younger and older men may indicate that younger men are becoming more comfortable performing certain aspects of femininity. This perhaps reflects a greater trend towards playing with gender and comfort in gender-expansiveness or perhaps reflects women’s speech becoming less associated with women and more acceptable in general society as time passes.

It is important also to recognize that stand-up comedy is unique among linguistic discourse contexts, as there is no back-and-forth. Since stand-up language is monologuing rather than conversational, this may factor into how speakers perform gender, and it sets this study apart from earlier studies like Lakoff’s.

Looking forward, there are multiple ways to expand this study to include a more diverse group of comedians. One way to do this would be to examine how supposed ‘gender’ differences look when race is accounted for. Lakoff and other researchers focused their observations on white women – therefore, women (and men) who aren’t white may actually display very different expressions of language, with different characteristics and perhaps at different frequencies.

Another forward-looking study could include comedians of a gender-expansive experience. Comedians who are not locked to an identity as either ‘man’ or ‘woman’ may display yet even more different expressions of gender in their language. It’s important to include not just individuals who fit a binary definition of gender. Though this concept was much less spoken about during the original studies conducted in the 1970s-1990s, society more willingly recognizes the expansive nature of gender and performance now, and linguistic study should not only reflect that sentiment but set out to describe how it fits in with language and linguistic study.

With ever-persistent debates about whether language will ever really be as egalitarian, as gender-neutral, as inclusive as we want it to be (“Women are witches, men are studs”), it is our job as linguists to catalog, describe, and advocate for change on the linguistic level so that it can influence and be influenced by the social level.

References

Cameron, D. (1997). Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In On Language and Sexual Politics (1st ed., pp. 47-64). Taylor & Francis Group.

Fischer, J. L. (1958). Social influences on the choice of a linguistic variant, WORD, 14:1, pp. 47-56, DOI: 10.1080/00437956.1958.11659655

Gordon, Mo. (2023, April 13). ‘Women are witches, men are studs.’ Universiteit Leiden, www.leidenlanguageblog.nl/articles/women-are-witches-men-are-studs-blog-mo-gordon.

Güvendir, E. (2015). Why are males inclined to use strong swear words more than females? An evolutionary explanation based on male intergroup aggressiveness. Language Sciences, vol. 50, pp. 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2015.02.003

Lakoff, R. (1998). Extract from Language and woman’s place. In D. Cameron (Ed.), The Feminist critique of language: A reader (2nd ed.) (pp. 242-252). London, England: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Solbes-Canales, I., S. Valverde-Montesino, & P. Herranz-Hernández. (2020). Socialization of gender stereotypes related to attributes and professions among young Spanish school-aged children. Frontiers, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00609/full.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. Ballantine Publishing Group.

TED. (2014, July 31). Men, women and language — a story of human speech | Sophie Scott | TEDxUCLWomen. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iteK4P0nDO8

Appendix

Video Links:

Men in Therapy – Gianmarco Soresi

Women are Smarter than Men – Bill Burr

Feminists Want to be Men – Andrew Schulz

Feminism and Womanhood – Taylor Tomlinson

Men’s Interpretation of Feminism Now – Erica Rhodes

Women’s Hooters – Whitney Cummings

Feminist About Paying – Bonnie McFarlane

Transcripts: