My Poor Little Meow Meow: K-Pop Fans and the Parasocial Abuse of Positive Politeness

Blai Puigmal Burcet, Emma Montilla, Latisha Sumardy, Sophia Wang

Korean popular music (K-pop) started off as a small subculture in the 1990s but began taking off in the West in the mid-2010s and since then has become increasingly popular and mainstream. K-pop fans are known for their borderline obsessive behavior and for finding personal validation through parasocial relationships (Kim & Kim, 2020), fostered by their online communication style. Social media as a mode of communication is unique due to its lack of a second interlocutor and how people take the tactics they use online to real-life interactions. We analyzed language use among English-speaking K-pop fans online, specifically regarding inappropriate usage of positive politeness strategies (PPS) towards celebrities. We hypothesized that tweets directed towards male celebrities will contain more PPS than those directed towards female celebrities. After analyzing replies to BTS and Blackpink, we confirmed our hypothesis as there is 2.6 times as much PPS usage in BTS’s replies versus Blackpink’s replies. The sudden and immense popularity of K-pop, stan culture, and the obsessive tendencies of fans is evident not only in the abuse of PPS online, but also in real life as we begin to see instances of fetishization of Asian American men.

Introduction/Background

K-pop has piqued our interest because the industry itself intentionally encourages fans to develop a parasocial relationship with celebrities. They succeed in this by publishing large amounts of content in the form of live broadcasts, vlogs, Instagram posts, collectible trading cards of idols included in albums, fansigns, etc. that all fabricate a sense of closeness and personal connection with the members of the group. (Ardhiyansyah et al., 2021) Fans pride themselves on knowing as much as they possibly can about members of their favorite groups, and it is common to make “guide” videos for new fans to get familiar with their faves. An example is YouTube user JinHit’s video “who is BTS? (un)helpful guide to BTS” (2021) that catalogs each BTS member’s quirks and habits for fans to memorize. Fans have also developed a K-pop-specific vocabulary that utilizes Korean loanwords to refer to different practices in the fan community, and there are entire guides on this as well, such as kpoptrash’s “a beginner’s guide to kpop vocabulary” (2020). We focused on English-speaking fans because we are interested in the explosion of K-pop’s popularity in America and the global West, and how their borderline obsessive behavior affects how they interact with real life Asian populations.

We focused on positive politeness strategies (PPS) used by K-pop fans on social media towards their favorite celebrities. According to Brown & Levinson (1987), PPS is typically reserved for use between interlocutors that have a close relationship. It includes specific linguistic features such as compliments, inside jokes, and nicknames, as it represents a language that is more personal, authentic, and used in informal situations between family and friends. When it is misused, PPS becomes a negative face threatening act that does not respect the interlocutor’s personal agency. In our case, PPS is being misused by fans towards celebrities with whom they have a one-sided relationship. They do not have a realistic chance of getting a response from these celebrities, but interact with them in a parasocial way as if they did. This particular use of PPS contributes to the fetishization of Korean celebrities, setting a precedent of inappropriate interactions that bleed into real life and how K-pop fans interact with average Asian American men. We expect to see that more PPS will be directed at men than women, and that the rise of K-pop fan communities and fan specific interactions has correlated to a rise in fetishization of East Asian men.

Methods

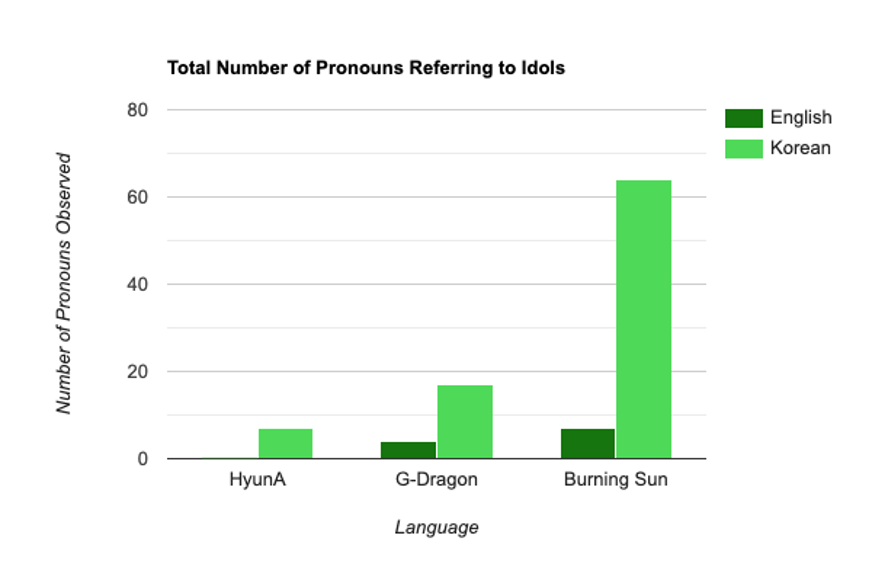

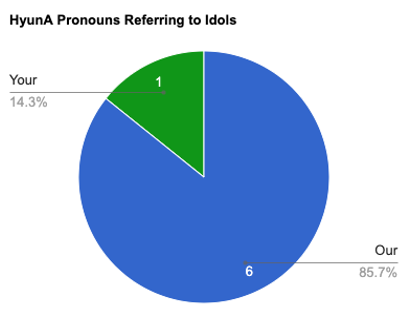

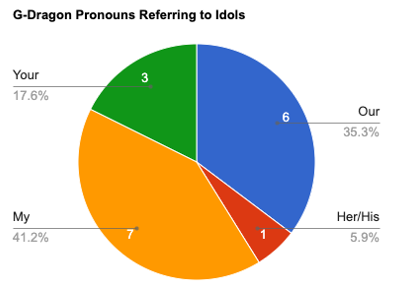

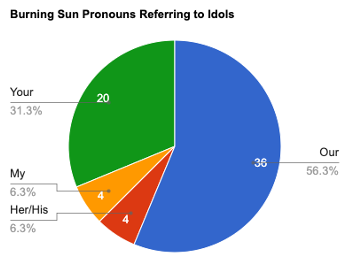

For this study, we decided to analyze the responses to 7 BTS and 7 Blackpink tweets from their official Twitter accounts, @BTS_twt and @BLACKPINK. We chose BTS and Blackpink because in terms of sales they are the biggest K-pop boy and girl groups in the West (McIntyre 2022), and we believe that analyzing fan interactions with these groups provides a baseline for how Western fans would interact with other K-pop groups as well. We picked the first 25 users’ replies in English under each chosen tweet. From our data pool, we omitted any tweets that either consisted of one-word phrases or were in mixed English and another language in order to make sure that our data was consistent. In total, we collected 350 users’ replies to these 14 tweets. The specific criteria that we looked for in the data were instances of fans using nicknames versus using the artists’ real names; any use of intimate language such as terms of endearment or diminutives or intimate verbs like “to love”; use of possessive language such as “my” or “our” in reference to these celebrities; and any direct 2nd person statements in the replies.

In regard to our target population, we decided not to narrow down our subjects by any specific age, gender, or location due to the anonymous nature of Twitter as a social media platform. Anonymity plays a big role in how people talk to each other online, as a prominent feature of social media is the comfort of not being able to see the person that you are sending the message or reply to. Because of this, we decided that age, gender, and location would not have a very strong impact on how people online would interact, and would be difficult for us as researchers to confirm based on looking at each Twitter user’s profile alone. However, we expect that the average English-speaking K-pop fan would probably be a female teenager located in the United States.

Data Analysis

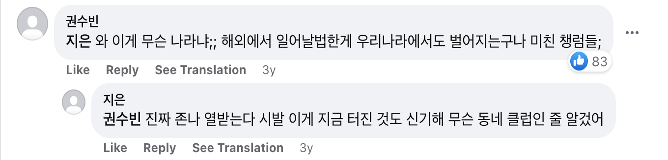

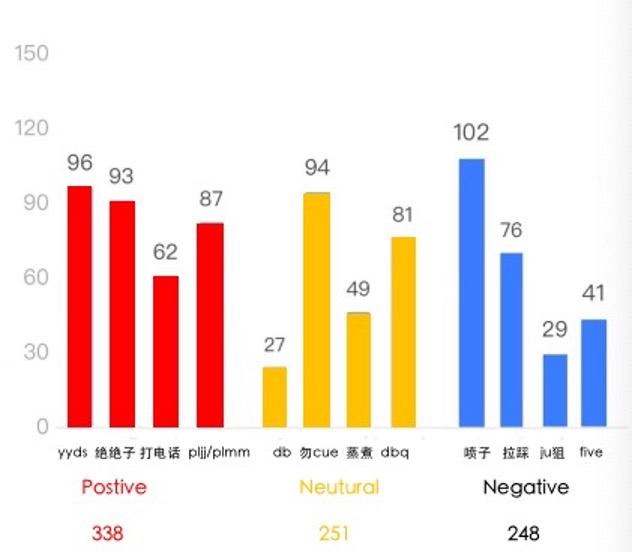

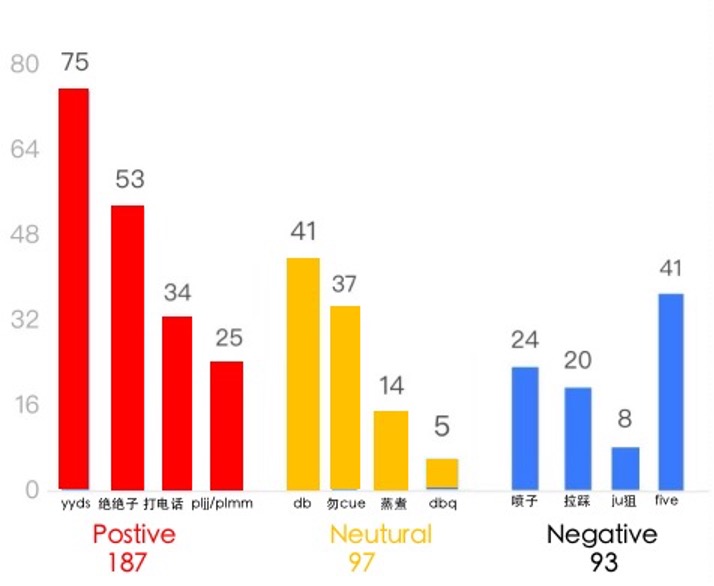

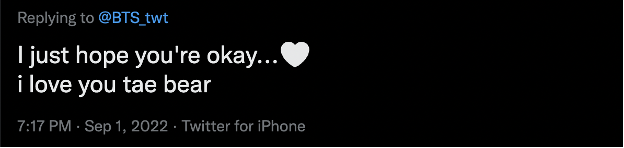

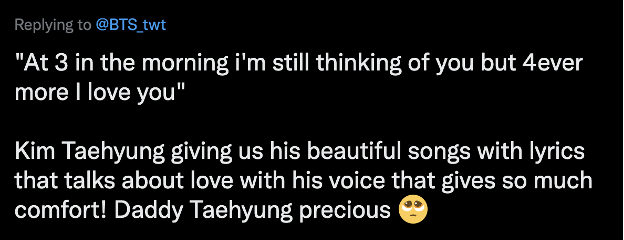

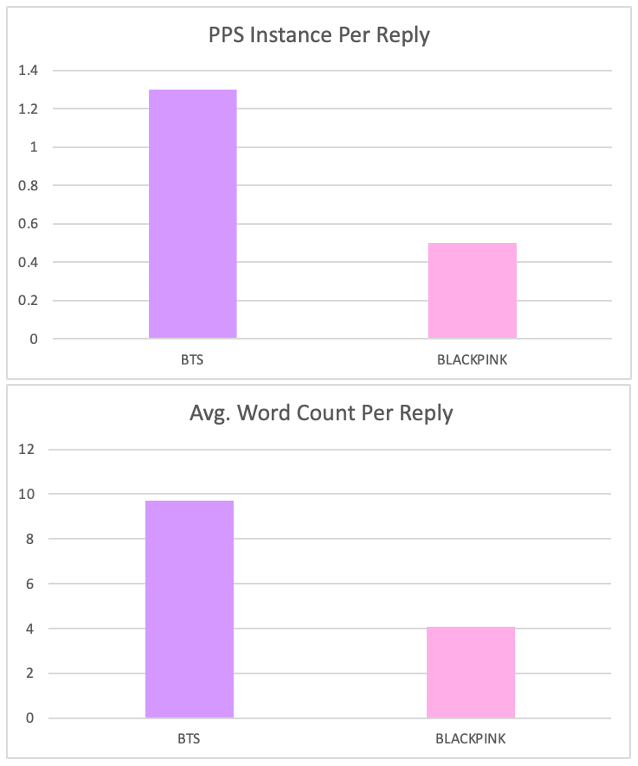

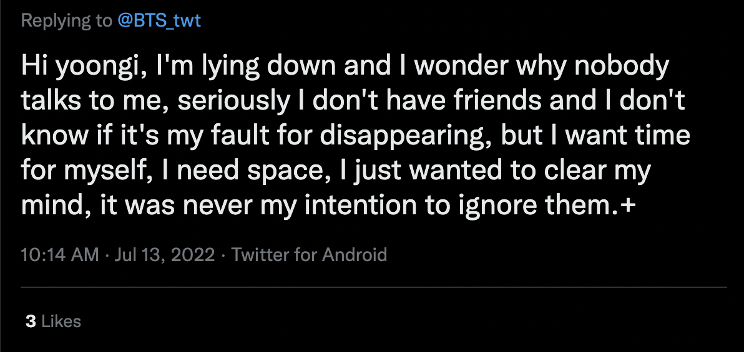

Initially, we found that there were about 1.3 instances of PPS per BTS reply versus 0.5 instances of PPS per Blackpink reply. The average word count of a reply to BTS was 9.7 words, and the average word count of a reply to Blackpink was 4.1 words. This difference in word count means that the average response to Blackpink reads something like “Jennie is such a queen”, while the average reply to BTS looks more like this:

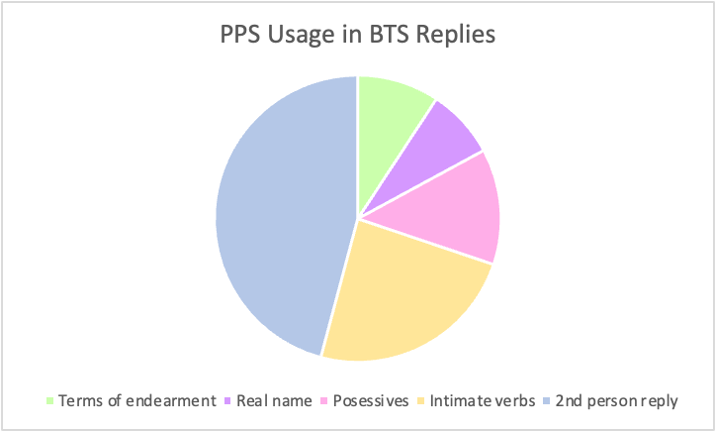

The most commonly used word overall in BTS’s replies was “you”, which co-occurred the most with verbs “love” and “miss”. BTS members were more likely to be referred to by their real names or nicknames chosen by fans rather than their stage names as well. The second-person reply containing “you” was by far the most commonly used instance of PPS, followed by intimate verbs.

There was a similar pattern in Blackpink’s replies: the most commonly used word was “you”, but it was more often referring to YG, Blackpink’s management company, rather than Blackpink themselves. The most common co-occurrence with “you” was still “love”, although miss did not appear in the sample at all. The most used PPS category once again was the 2nd person reply followed by possessives “my” and “our” and then intimate verbs.

The higher word count in BTS’s replies correlated with more personal messages, where fans would overshare in a reply thread about their hardships, especially to do with their lack of an IRL social life. Although it doesn’t fit into the specific PPS criteria defined earlier, it qualitatively shows the one-sided relationship between BTS and their fans and what the fans feel comfortable saying online. Higher word average word count could also explain why there are more PPS usages per tweet in the BTS sample.

More cute, romantic terms of endearment were used to describe BTS in their replies, while Blackpink fans were more likely to use terms of endearment to praise their performance and talent. The most common term for BTS was “baby” while, in comparison, the most common for Blackpink was “queen”. BTS’s fans were also more likely to make up their own nicknames for the members, while Blackpink fans stayed consistent with each other. For example, Blackpink’s rapper Lisa was called only Lisa or Lalisa, while BTS’s V was called a whole group of different names, including but not limited to Taehyung, Tae, Taetae, Taebear, and Jubbly. No one in the sample referred to him solely as V, the name he performs under. BTS fans were also more likely to refer to the artist as “boyfriend” or “bf” than Blackpink fans were to call the artists their “girlfriend” or “gf”.

There is a difference between the way BTS and Blackpink’s Twitter accounts are presented which could partially account for the difference in fan interactions: @BTS_twt is made to seem like the members themselves are posting, while @BLACKPINK is clearly run by their management and is more promotional than personal in nature. BTS’s posting style on Twitter, which gives a closer (although still heavily stylized and manufactured) look at the artists’ lives, could incentivize posting more personal replies if it seems like BTS could potentially see or even interact with them. This is what leads to fans feeling comfortable utilizing PPS in one-sided interactions with BTS, while Blackpink’s style of social media posts keeps their fans at a distance and makes sure that they know they are celebrities rather than their friends. Blackpink has also had consistent issues with their management underpromoting them and leaving out certain members in promotional material, so fans who know this and know that Blackpink’s company is running the account will not feel as comfortable being intimate with a corporation that is causing issues for their idols.

Discussion and Social Implications

Overall, we found that there was 2.6 times as much PPS usage per reply to BTS than per reply to Blackpink. The word choice in BTS’s replies was also more diminutive and focused on their cuteness rather than attractiveness or talent, and contained suggestions of a one-sided relationship that was not present in Blackpink’s replies. So what does this mean, and how does it affect Western society?

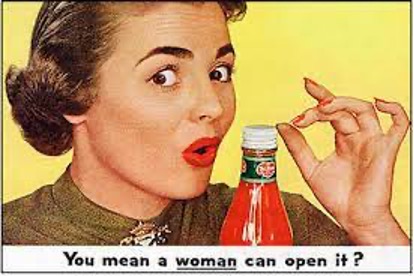

Historically, in the Western world, women tended to be infantilized while men were not. For example, newborn baby girls have been described as “sweet” four times as often as little boys, and many advertisements targeted towards women often depicted them as incompetent and child-like (Huot 2013).

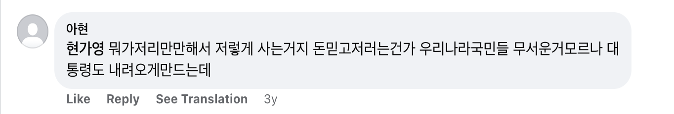

Our data goes against this Western gender norm as we see evidence of the male group being more infantilized and diminutized than the female group. And it doesn’t stop at celebrities: the obsessive desire for a relationship with these idols has leaked into reality and now affects the Asian American male population. Previously in America, Asian men in the dating pool were stereotyped as effeminate and asexual (Kao 2018) but there has been a shift in how American women view Asian men as romantic or sexual objects because of the popularity of K-pop.

For example, from Stewart (2021):

Some Asian American men even think the K-pop phenomenon, which is often heralded as a boon for Asian male representation, is causing a fetishization of certain types of Asian men that complicates their love lives. [One] says he recently matched with a girl on Tinder who wrote in her bio that she was ‘looking for her K-pop boyfriend.’ He says her bio made him feel uncomfortable, and he didn’t meet up with her, since he wants to be seen for who he is, not as an embodiment of a stereotype.

This phenomenon has also begun to affect the K-pop industry itself: as the popularity of boy groups increase in the West, they lean into the audience’s desires and develop softer, more subversive (from a Western perspective) personas. According to Lee et at. (2020), many Westerners are drawn to Asian masculinity and find it “refreshing” and project this desire onto male celebrities as well as Asian men they encounter in real life. This produces a positive feedback loop of online fans infantilizing BTS, and then BTS increasing their cuter concepts in their promotional materials to cater to those fan desires, which then affect real life interactions.

K-pop fans have also begun to apply the same “stanning” techniques to Korean celebrities outside of the idol industry, such as breakout star of the 2022 World Cup Cho Gue-sung, a player on the South Korean national team. Tweets have surfaced from K-pop fans comparing him to idols purely because of his ethnicity and using PPS in tweets about him they would typically use for K-pop stars. (Youn, 2022) Even though as an athlete Cho already fits into a more stereotypically Western masculine archetype, he is not free of the soft, cute stereotypes that have already been applied to Korean idols before him.

Conclusion

Some may say that it is a positive thing, or a compliment to these celebrities and Asian men, that they are now the ones being sexualized after decades of asexual stereotypes and low romantic desire in the Western world (Stewart 2021). However, this is not the “equality” we should strive for. Fetishization is a form of discrimination and racism that affects real people and communities, not just the far away idols on social media in a different continent. We should not be infantilizing or fetishizing women, Asian men, or anyone. We should also question how social media allows these internet communities to encourage this behavior. The internet is a valuable tool for bringing people together, but it also houses insidious communities that can easily and accessibly indoctrinate users into harmful mindsets.

References

Ardhiyansyah, A., Maharani, D., Permata, S. S., & Mansur, U. (2021). K-pop marketing tactics that build fanatical behavior. Nusantara Science and Technology Proceedings, 66–70. http://nstproceeding.com/index.php/nuscientech/article/download/396/381

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

JinHit. (2021, May 25.) Who is BTS? (un)helpful guide to BTS (2021) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkSGKGJYe4k

Kao, G., Balistreri, K. S., & Joyner, K. (2018). Asian American men in romantic dating markets. Contexts, 17(4), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504218812869

Kim, M., & Kim, J. (2020). How does a celebrity make fans happy? Interaction between celebrities and fans in the social media context. Computers in Human Behavior, 111,106419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106419

Kpoptrash. (2020, February 11.) A beginner’s guide to kpop vocabulary [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvigAv2mW5c

Lee J.J., Lee, R., & Park, J. (2020). Unpacking k-pop in America: The subversive potential of male k-pop idols’ soft masculinity. International Journal of Communication, 14, 20. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/13514

Stewart, J. Y. (2021, August 5.) How America tells me and other Asian American men we’re not attractive. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/life/i-grew-up-thinking-being-asian-detracted-from-my-masculinity-heres-how-america-tells-me-and-other-asia n-american-men-theyre-not-attractive/

McIntyre, H. (2022). Blackpink ties Twice for the most bestselling albums in the U.S. among women in k-pop. Forbes Hollywood & Entertainment. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hughmcintyre/2022/09/30/blackpink-ties-twice-for-the-most-bestselling-albums-in-the-us-among-women-in-k-pop/?sh=752b00107909

Youn, S. (2022, December 7.) How Cho Gue-sung became the breakout thirst trap of the World Cup. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/cho-gue-sung-became-breakout-thirst-trap-world-cup-rcna60525