Madeline Doring, Abigail Garza, Julian Goldman, Dylan Sherr, Faye Turcotte

From high school hallways to corporate backchannels, gossip is everywhere. But what if the whispers are pointing to something more profound about how we’re communicating, who’s holding power, and how cultural norms are getting passed on and contested? To understand this from a closer standpoint, we examined the portrayal of gossip along gender and generational lines in the media with an emphasis on rethinking the cultural worth and communicative role of gossip. Gossip has traditionally been dismissed as frivolous or emotionally illogical, but researchers have begun to understand it as a socially significant practice. Based on sociolinguistic theories of gendered communication, we compared select instances of gossip from TV shows for two generations. Our results cemented gossip as a prism for understanding identity, power, and belonging in general cultural awareness. It not only functions as a social glue but also as a channel whereby people negotiate group dynamics and social norms.

Introduction and Background

Stereotypes associated with gossip divert from its basic communicative, relational, and cultural functions. Gossip is constantly misunderstood as idle chatter in scholarly as well as popular discourse. Recent research in psychology, communication science, and organizational behavior has reframed gossip as a socially strategic action. Gossip has been shown to be critical to social coordination, identification, and norm enforcement as a primary way in which individuals acquire knowledge about both others and themselves (Dores Cruz et al., 2021). Through our study, we examined these ideas from the specific perspective regarding how gendered depictions of gossip have evolved across generations within popular media, namely television dramas.

Before looking into this, we were already aware of previous information regarding gendered patterns of gossip, i.e., the idea that women and men gossip differently. Past research characterized women as gossiping primarily about relationships and personal matters so as to participate in social bonding, whereas men gossip to acquire humor or attain status (Levin & Arluke, 1985). Current research maintains this trend, with women participating in emotion-focused, relation-directed means of gossip in the context of coalition-building (Davis et al., 2018). We also know that men, on the other hand, gossip far less overall and use gossip in instrumental functions as a way to navigate social positioning. Such behaviors cohere with Deborah Tannen’s theoretical framework, distinguishing “rapport talk”, a related, connection-directed characteristic of women, and “report talk,” an informational, hierarchical characteristic of men (Van Herk, 2018).

Despite the fact that such patterns have long since taken root, there was no framework to comprehend the way in which media representations reinforce or challenge these gendered communication norms in the long run–the leading question guiding our own research. While prior research has explored gendered patterns in gossip, few studies have examined whether and how gossip has evolved across generations or been portrayed differently over time in television. This gap in the literature motivated our study, as we aimed to investigate whether shifts in gender norms were mirrored in media discourse. With continued influence from television to the public eye regarding social conduct, the issue we examined involved whether gender representations in gossip have shifted in sync with gender norms. With this, our research documents the construction of gossip across two periods (1990s–2000s, 2009–2022) in U.S. television with attention to gender. By combining empirical content analysis with sociolinguistic theory, our analyses help demonstrate the idea that gossip is neither fixed nor gendered; it is an evolving social practice.

Methods

In terms of gossip across different generations and genders, we were more interested in how TV shows categorized gossip across two distinct periods and how female-identifying individuals differed in their communication features from male-identifying individuals. First and foremost, we coded for gender identity based on the pronouns that were used in the show. We analyzed different TV shows representing two generational periods. The first period involved shows that were released between 1997-2009, including Friends (Seasons 5 and 8) and Survivor (Season 6). The second period involved TV shows released between 2009-2022, including Love Island (Seasons 1 and 2), Outer Banks, and The White Lotus. All of these episodes were accessed through streaming platforms, including Netflix and Hulu. Because television remains a powerful force in shaping public understandings of identity and interaction, analyzing TV dialogue allows us to observe how gossip reflects or resists evolving social norms.

For each of these shows, we chose approximately three scenes, each around 2 minutes in duration, that featured confrontation, gossip, or situations that all displayed differences between how the two identities communicated with one another. A total of 15 scenes were analyzed and transcribed across all shows. By observing the contrast between individuals, there was an exposure to how gossip can be challenged, and it allowed us to gain insight into each generational period. So, we assessed the prevalence of communication features in the scenes in the two periods of time.

*See Figure 1 below for an example of our transcriptions.*

Figure 1. Transcription from Friends (Season 5, Episode 9), showing a gossip scene used to analyze gendered communication styles like humor and confrontation.

Each television scene was analyzed using six communication features, each previously associated with gendered communication and gossip behavior: indirectness, report, rapport, humor as a shield, status assertion, and meta-commentary. For example, we see indirectness in Love Island when Caro and Cashel are talking about other couples as well as themselves. Caro, who identifies as female, says “ °hh I just (0.3) feel like (0.4) you’re not being ↑honest with me.” Use of the words “I just feel like” indicates hedging, suggesting Caro’s unwillingness to be straightforward due to nerves about how her words may be perceived. In response, Cashel, who identifies as male, says “ <<laughing> I guess I’m just the worst boyfriend ever.>” He uses humor as a shield to avoid taking ownership of his behavior. We also observed a report talk in Friends, when Ross asks, “What’s going on?” to get a factual explanation of the situation, contrasting with rapport talk, like Harper in The White Lotus confiding in Ethan to build emotional alignment over shared social discomfort. Status assertion occurred in Survivor, where one contestant claimed, “They’re playing us,” in an attempt to establish control over the narrative. Lastly, meta-commentary was seen in Outer Banks, when a character prefaced gossip with, “I know we’re being shady, but hear me out…” acknowledging the act of gossiping itself.

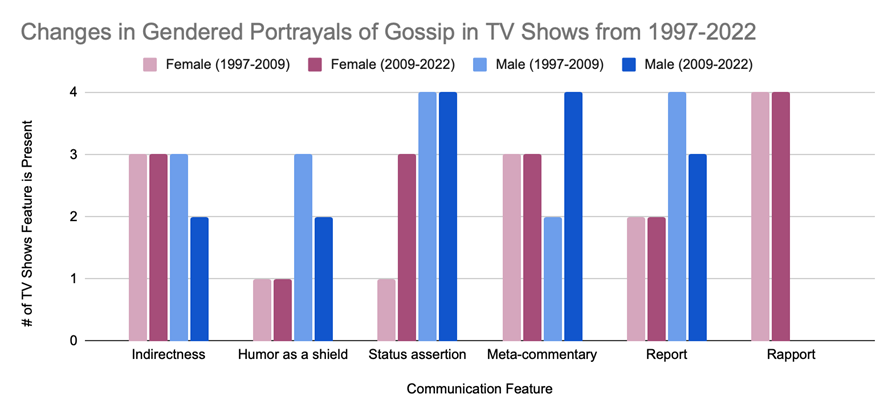

Figure 2. Bar chart comparing six gossip features across male and female characters from two TV generations (1997–2009 and 2009–2022), based on average frequency.

Figure 2, a grouped bar chart, compares the previously mentioned communication features across male and female characters in TV shows from two time periods: 1997–2009 and 2009–2022. The X-axis contains the coded communicative traits, while the Y‑axis shows their average frequency on the 0–4 scale. The pattern is striking: use of gossip communicational features by female characters in TV shows remained relatively consistent across the periods, while portrayals of male gossip noticeably shift, especially in regards to a reduced use of humor and indirectness. This suggests a slow blending of gendered language styles, even as clear differences persist.

In addition to data, we analyzed specific TV scenes to demonstrate these trends across contexts. Figure 3 features a moment from the White Lotus, between husband and wife, Ethan and Harper. In one scene, Harper attempts to gossip with Ethan about the other couple they are traveling with, whom she sees as fake, snobby, and arrogant (White, 2022). She uses an indirect style of gossip to assert her status as well as gain rapport from her husband, exemplifying the modern portrayal of female gossip both strategically and socially.

Figure 3. Scene from The White Lotus (Season 2, Episode 2), showing indirect and strategic gossip between characters Harper and Ethan.

To situate our project within real-world discourse, we included several informal references. A TEDx Talk titled “Why gossip is good” by Assem Bisenbay breaks down gossip’s benefits in modern society (Bisenbay, 2019). Another TEDx video, “The virtues of gossip” by Richard Weiner, echoes these ideas by arguing that gossip can foster social cohesion (TEDx, 2013). Additionally, a Reddit thread asking “Why do we love gossip?” offers everyday perspectives that parallel our findings about social bonding and status (CommonRash, 2022). Taking this media into account, our project was structured around five key ideas: gendered gossip, generational communication, TV media discourse, sociolinguistic method, and report vs. rapport talk. These pinpoint our population (TV characters), method (scene-based communication coding), and theoretical orientation. All TV show clips analyzed were publicly available; no private data or human subjects were involved. Our research is the collaborative work of Abigail Garza, Julian Goldman, Faye Turcotte, Madeline Doring, and Dylan Sherr, conducted under the mentorship of Professor Bahtina.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our findings across various scenes in TV shows contribute to the idea of gossip as a whole and what it truly means to privately discuss personal information with others through means of conversing. Gossip itself provides key insights into the ways in which individuals interact on a broader scale, both culturally and socially. In terms of gender and generational differences, studying gossip across all individuals can be used to highlight key aspects of the progression that can be seen in conversational analysis across genders. Through studying numerous television dramas, it can be seen that the ideas of report and rapport amongst male-identifying and female-identifying individuals remain true no matter the time period. This report vs. rapport stereotype can be generally accepted as being a ‘mainstay’ in the scene of gossip itself. So, although there are constant changes occurring in the world, there will still be aspects of gendered gossip that remain constant no matter where we are or what time it is.

References

Bisenbay, A. (2019, September). Why gossip is good [Video]. TED Talks. https://www.ted.com/talks/assem_bisenbay_why_gossip_is_good?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Burnett, M. (Executive Producer). (2003, April 3). Girls vs. boys (Season 6, Episode 8) [TV series episode]. In Burnett, M. (Executive producer), Survivor. CBS.

CommonRash. (2022). Why do we love gossip? Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/CasualConversation/comments/v9dyen/why_do_we_love_gossip/

Davis, A. C., Arnocky, S., & Vaillancourt, T. (2018). Sex differences, initiating gossip. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1–8). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_190-1

Dores Cruz, T. D., Nieper, A. S., Testori, M., Martinescu, E., & Beersma, B. (2021). An integrative definition and framework to study gossip. Group & Organization Management, 46(2), 252–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601121992887

Jonas, J., & Pate, S. (Writers), & Pate, J. (Director). (2020, April 15). The runaway (Season 1, Episode 8) [TV series episode]. In Jonas, J., Pate, J., & Pate, S. (Executive producers), Outer Banks. Netflix.

Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Writers), & Bright, K. S. (Director). (1998, December 17). The one with Ross’s sandwich(Season 5, Episode 9) [TV series episode]. In Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Executive producers), Friends. NBC.

Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Writers), & Bright, K. S. (Director). (1999, February 11). The one where everybody finds out (Season 5, Episode 14) [TV series episode]. In Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Executive producers), Friends. NBC.

Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Writers), & Bright, K. S. (Director). (2001, November 15). The one with the rumor (Season 8, Episode 9) [TV series episode]. In Kauffman, M., & Crane, D. (Executive producers), Friends. NBC.

Levin, J., & Arluke, A. (1985). An exploratory analysis of sex differences in gossip. Sex Roles, 12(3–4), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287594

Macleod, C. (Director). (2015, June 7). Episode 6 (Season 1, Episode 6) [TV series episode]. In Richard Cowles et al. (Executive producers), Love Island. ITV2.

Macleod, C. (Director). (2016, June 10). Episode 9 (Season 2, Episode 9) [TV series episode]. In Richard Cowles et al. (Executive producers), Love Island. ITV2.

TEDx Talks. (2013, November 19). The virtues of gossip: Richard Weiner at TEDxMiami 2013 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpiTp2COVZk

Van Herk, G. (2018). Gender. In What is sociolinguistics? (2nd ed., pp. 122–141). Wiley Blackwell. White, M. (Writer & Director). (2022, November 6). Italian dream (Season 2, Episode 2) [TV series episode]. In White, M. (Executive producer), The White Lotus. HBO.