Miroslava Albiter, Caitlin Morlett, Renee Ma, Jaquelin Trujillo, and Zirui(Ray)

Have you ever heard your friend or family speak two languages in one phrase? Have you ever spoken two languages in a sentence? We look deeper into how code-switching affects phonological convergence, specifically in Spanish-English bilinguals. A key phonological difference between English and Spanish is the articulation of word-initial voiceless stops such as /p/, /t/, and /k/. Therefore, we specifically analyzed how the Voiced Time Onset (VOT) measures of Spanish-English bilinguals are affected by code-switching between Spanish and English. Sixteen English-Spanish bilinguals were recorded and asked to read aloud the Rainbow passage, a passage with English sentences, Spanish sentences, and code-switched English-Spanish sentences. PRAAT was used to measure the participants’ VOTs to compare the differences to a baseline VOT measure of monolingual English and Spanish speakers (Castañeda Vicente, 1986; Lisker & Abramson, 1964).

After data collection and analysis, we discovered that both VOTs of English and Spanish were lengthened during code-switching, albeit for different reasons. As Spanish VOT extended due to phonological convergence, English VOT also unexpectedly extended. We observed evidence for hyper-articulation, which can further explain our conclusion. However, limitations are reckoned with, and thus, fields of phonological change within code-switched contexts are explored.

Introduction and Background

In this article, we investigated code-switching in English-Spanish bilingual college students, focusing on their phonological change along with the process of code-switching through Voice Onset Time. Code-switching “is a practice common among bilinguals whereby speakers use both languages in a single utterance” (Balukas & Koops, 2015). We will analyze whether English-Spanish bilingual college students demonstrate phonological convergence of VOT in code-switching sentences. The age range of the 16 tested participants varies, with 14 being 20 years old and the other two between 40 and 50 years old. After collecting data, we examined the Voice Onset Time (VOT) in different circumstances and the subsequent phonological convergence in English-Spanish code-switched sentences.

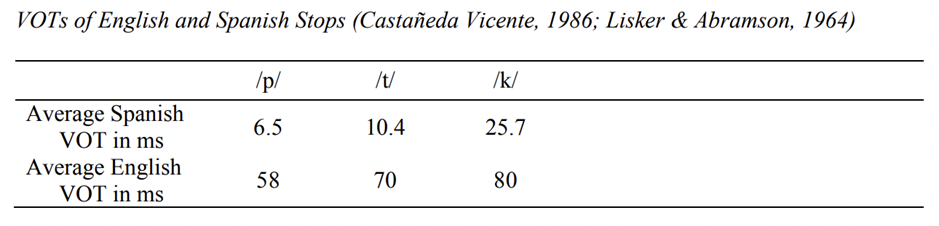

According to previous research, English monolingual speakers typically produce a longer VOT of word-initial voiceless stops than Spanish monolingual speakers (Balukas & Koops, 2015). Samples from bilingual participants were collected and analyzed using Praat, with a particular focus on VOT changes and the evidence of subsequent phonological convergence. As such, we are investigating a potential phenomenon wherein the English VOT is observed to shorten while the Spanish VOT lengthens in English-Spanish code-switched sentences. This dynamic interaction may be further interpreted as evidence of phonological convergence, reflecting an underlying adjustment mechanism within bilingual speech production systems. Due to the lack of ready access to true monolingual speakers in the LA area, we will use data from the BYU Scholars Archive to compare the VOT of our bilingual speakers to the average VOT for /p/, /t/, and /k/ in both English and Spanish. In the BYU Scholars Archive, the Spanish baseline was recorded at the University of Barcelona in 1986 and was taken from 10 monolingual Spanish speakers (Castañeda Vicente, 1986). The English baseline in the archive was recorded at the University of Pennsylvania in 1964 based on 4 American monolingual English speakers (Lisker & Abramson, 1964).

Figure 1 – Chart from BYU Scholars Archive showing the average VOT is ms for English bilinguals and Spanish bilinguals

Phonological properties, including VOTs, can be differentiated across various dialects, even within the same language. In this research, our participants predominantly speak LAVS (Los Angeles Vernacular Spanish), while three speak the Castellano dialect.

In this study, we will investigate whether code-switching influences VOT in English-Spanish bilingual speakers. Testing the specific phonological changes in VOTs in English and Spanish during code-switching. It finally aims to detect the phonological convergence during code-switching in English-Spanish bilinguals. Our hypotheses of VOT and phonological convergence are as follows:

- English-Spanish bilingual speakers will shorten English VOT and lengthen Spanish VOT compared to true monolingual speakers of each respective language.

- If the speaker’s L1 is English and their L2 is Spanish, we expect the VOT for Spanish /p/, /t/, and /k/ to be longer than Spanish monolingual speakers. We also expect their English VOT for /p/, /t/, and /k/ to reflect the VOT of monolingual English speakers.

- If the speaker’s L1 is Spanish and their L2 is English, we expect the VOT for English /p/, /t/, and /k/ to be shorter than English monolingual speakers. We would also expect their Spanish VOT for /p/, /t/, and /k/ to reflect the VOT of monolingual Spanish speakers.

If a participant has been discouraged from speaking Spanglish, they will be more likely to have longer VOT in Spanish despite differences in their L1 or L2.

To clarify related concepts, VOT is “the temporal relationship between laryngeal pulsing and the onset of consonant release” (Molfese & Narter, 1997). Phonological convergence, on the other hand, refers to the process by which speakers in a communicative interaction adjust their phonological patterns—such as pronunciation, intonation, or rhythm—towards one another. A key phonological distinction between English and Spanish arises primarily in articulating word-initial voiceless stops, namely /p/, /t/, and /k/. Positive VOT, or aspiration, is characterized by a puff of air following the release of the stop.

A phonological rule of English specifies that word-initial voiceless stops are aspirated or have a positive VOT. Word-initial voiceless stops in Spanish are typically not aspirated or aspirated, much less than English word-initial voiceless stops (Piccinini & Arvaniti, 2015). We will explore Voice Onset Time in code-switching contexts. Code-switching “is a practice common among bilinguals whereby speakers use both languages in a single utterance” (Balukas & Koops, 2015). We will analyze whether English-Spanish bilingual college students demonstrate phonological convergence of VOT in code-switching sentences.

Methods

We will first have all participants complete the demographic and self-report questionnaire about their linguistic background. The questionnaire will include information about their L1 and L2, how often they code-switch, their proficiency in speaking and reading both languages and if they speak any other languages. Lastly, we will include sociocultural questions about their language use, including how positively or negatively they feel about speaking Spanglish and if they have ever been discouraged from speaking Spanglish.

The participants will read “The Rainbow Passage,” a context that includes a mix of English-only sentences, Spanish-only sentences, and sentences that switch from English to Spanish or Spanish to English. We will account for individual idiosyncrasies while striving to derive principles that are as generalizable as possible. The participants will read the following paragraph adapted from the Rainbow Passage with pre-written code-switched sentences:

When the kind sunlight strikes cold raindrops in the air, they act as a prism and form a rainbow. El arcoiris divide la luz blanca en muchos colores hermosos. Estos toman la forma de un arco tan largo, with its path high above, and its two ends apparently beyond the horizon. There is, according to legend, a boiling pot of gold at one end. People look, pero nadie lo encuentra. Cuando un hombre busca algo más allá de su alcance, sus amigos pueden decir que está buscando la olla de oro al final del arcoíris. Throughout the centuries, people have explained the rainbow in various ways. A recording device will be used to record samples of participants using Praat to measure the phonetic output of the individuals and the length of VOT across all conditions. The English words from the Rainbow Passage that we will analyze include kind, cold, two, to, pot, and people. The Spanish words from the Rainbow Passage that we will be analyzing include colores, toman, tan, pero, cuando, and pueden.

Results and Analysis

Several group members contacted qualified bilingual participants and provided access to the prerequisite questionnaire. After collecting basic information about their first language acquisition (FLA) and second language acquisition (SLA) or second language learning (SLL), we distributed the altered Rainbow Passage to participants, ensuring that the recordings of their utterances were clear and suitable for further analysis. We then reviewed all recordings for quality and completeness before forwarding them to those responsible for data analysis. Audio recordings were collected and analyzed using Praat to find the VOT length. The data collected using Praat for each of the 16 participants is grouped into different categories in order to test the following hypotheses.

- Average bilingual /p/, /t/, /k/ VOT compared to monolingual /p/, /t/, /k/ VOT (BYU)

- Group English L1 speakers /p/, /t/, /k/ VOT and compare to Spanish L1 speakers /p/, /t/, /k/ VOT

- The average /p/, /t/, and /k/ VOT for both languages was based on whether or not they were discouraged from speaking Spanglish.

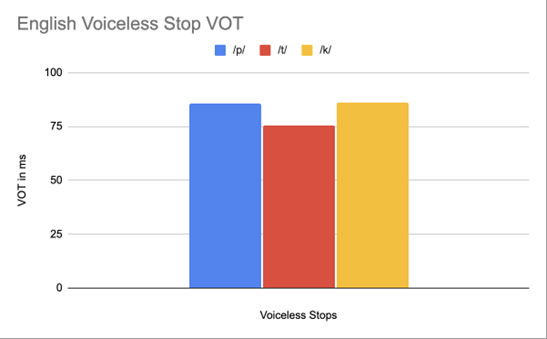

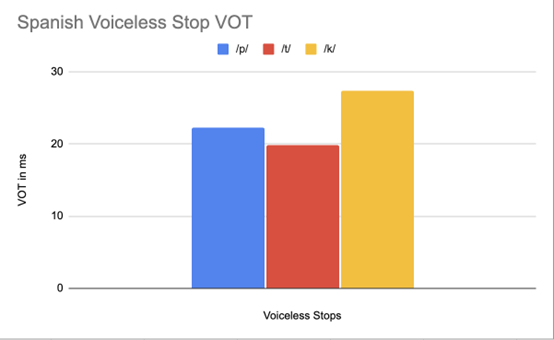

Based on our data grouping, we discovered that our first hypothesis was false because the English VOT mean values for all 16 of our participants (/p/ 85 ms) (/t/ 75 ms) (/k/ 86 ms) were longer than our baseline measurements. Our Spanish voiceless stop mean values based on 16 participants (/p/ 22 ms) (/t/ 75 ms) (/k/ 27 ms) had a /p/ and /t/ value that was longer than the baseline measures, but the /k/ mean was similar to the baseline data.

Figures 2 and 3—The graph shows the mean VOT in milliseconds for all 16 participants. Figure 2 displays the English VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow). Figure 3 shows the Spanish VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow).

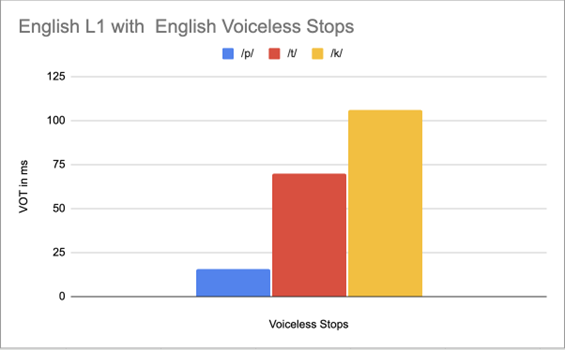

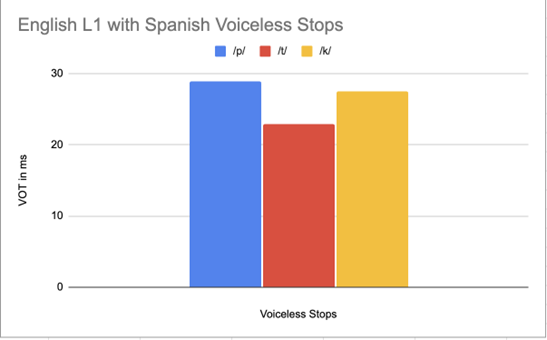

We found our second hypothesis partially correct because our Spanish VOT was longer than the baseline data, but our English VOT was also longer than the English baseline. Our English L1 Spanish Voiceless mean VOT values (/p/ 28 ms) (/t/ 22 ms) (/k/ 72 ms) were longer than the VOT baseline data collected from Spanish monolinguals. Our English L1 English mean VOT values were similarly longer than those of English monolingual speakers in the baseline data.

Figures 4 and 5 – The graph shows the mean VOT in milliseconds for all participants with English as their first language. Figure 4 shows the English VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow). Figure 5 shows the Spanish VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow).

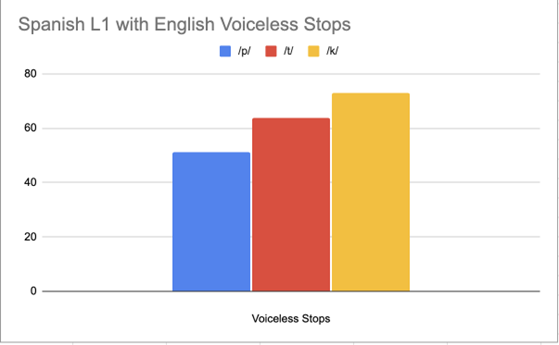

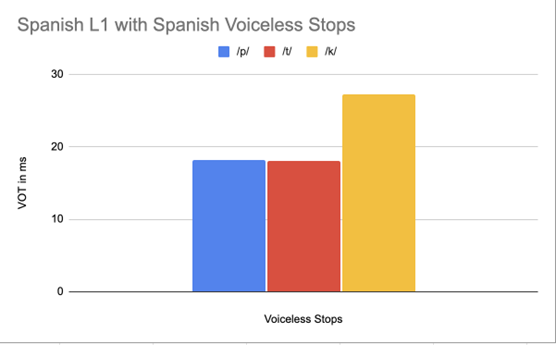

We discovered that our Spanish VOT was longer than our baseline for the /k/ voiceless stop, partially supporting our third hypothesis. Our Spanish L1 English mean VOT (/p/ 51 ms), (/t/ 63 ms), (/k/ 72 ms) was shorter than our baseline, as expected. When we looked at our Spanish L1 Spanish, mean VOT (/p/ 18 ms), (/t/ 18 ms), and (/k/ 27 ms), we discovered that the /p/ and /t/ mean VOT values were longer than the baseline, while the /k/ mean VOT value was identical to the baseline value.

Figures 6 and 7 – The graph shows the English VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow). Figures 6 and 7 show the mean VOT in milliseconds for all participants whose first language was Spanish. The Spanish VOT values for /p/ (blue), /t/ (red), and /k/ (yellow) are shown in Figure 6.

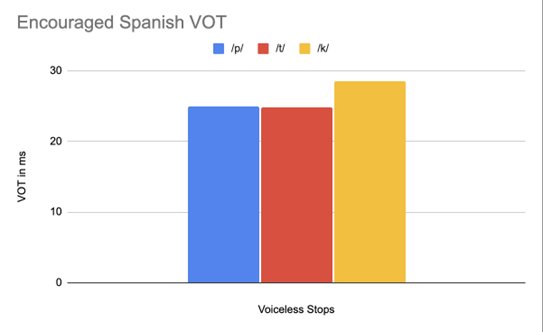

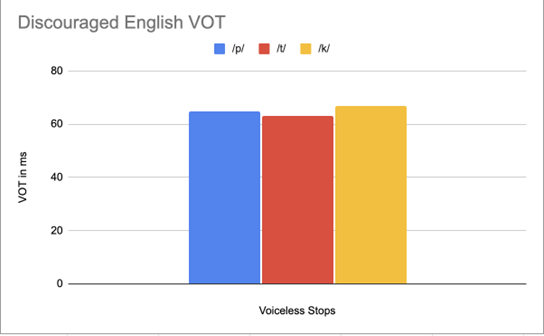

Since the participants who were discouraged from speaking Spanish had a lower VOT than those who were encouraged to speak Spanish, our fourth hypothesis was false. In comparison to our encouraged Spanish mean VOT, which is (/p/ 24 ms) (/t/ 24 ms) (/k/ 28 ms), our discouraged Spanish mean VOT was (/p/ 18 ms) (/t/ 18 ms) (/k/ 28 ms).

Figures 8 and 9—The graph shows the average VOT in milliseconds for each of the 16 participants according to whether they had been encouraged to speak Spanglish. The mean VOT in ms for the /p/, /t/, and /k/ values for the participants who received encouragement is displayed in Figure 8. The mean VOT in ms for the discouraged participants’/p/, /t/, and /k/ values are displayed in Figure 9.

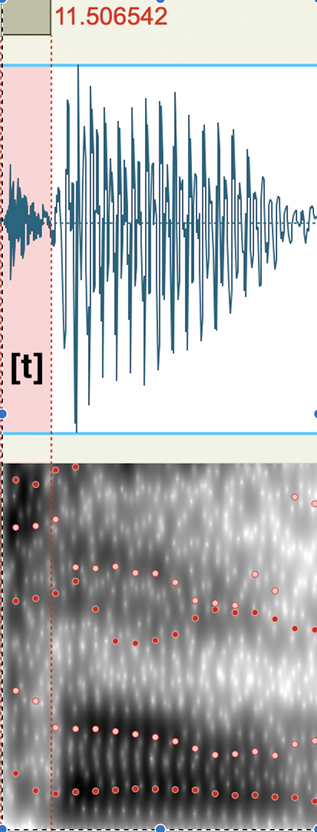

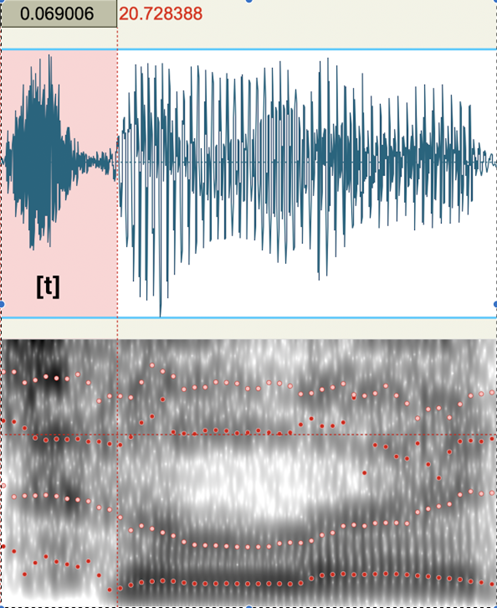

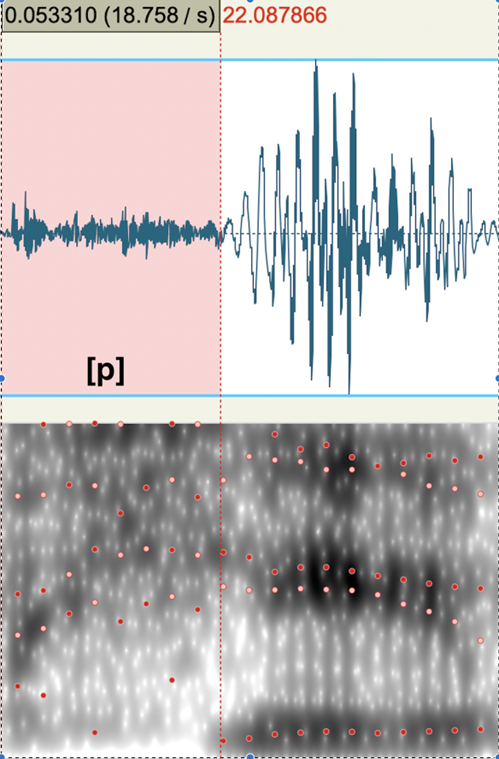

Figures 10 and 11 – Both are screenshots of the Praat spectrograms of one of our participants. The VOT of the participant who produced the [t] in the word “toman” is displayed in red in Figure 10 (left). The VOT of the participant who produced the [tʰ] in the word “to” is displayed in red in Figure 11 (right). Speaking Spanglish has been discouraged for this individual, whose first language is Spanish.

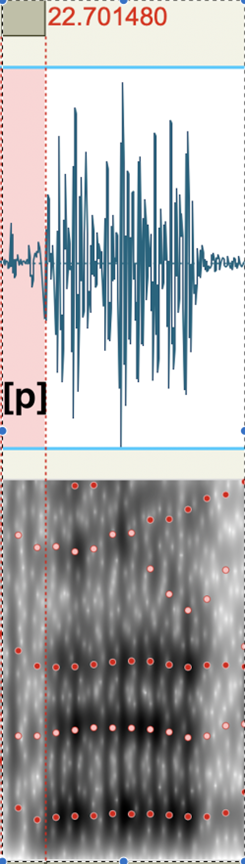

Figures 12 and 13 – Both are screenshots of the Praat spectrograms of one of our participants. The VOT of the participant who produced the [p] in the word “pero” is displayed in red in Figure 12 (left). The VOT of the participant who produced the [pʰ] in the word “people” is displayed in red in Figure 13 (right). Speaking Spanglish has been discouraged for this individual, whose first language is Spanish.

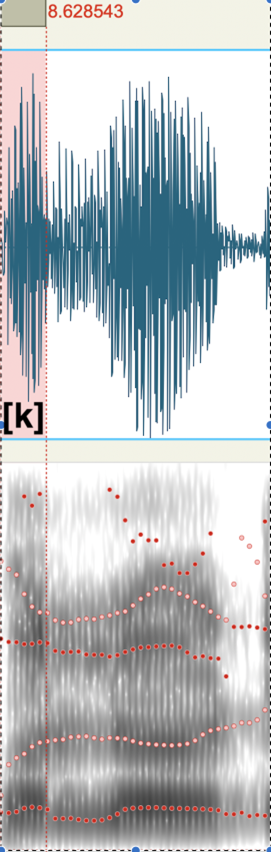

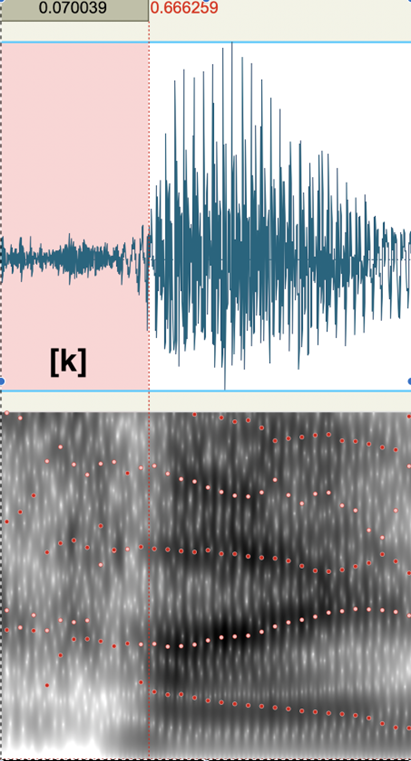

Figures 14 and 15 – Both are screenshots of the Praat spectrograms of one of our participants. The VOT of the person who produced the [k] in the word “colores” is displayed in red in Figure 14 (left). The VOT of the person who produced the [kʰ] in the word “kind” is displayed in red in Figure 15 (right). Speaking Spanglish has been discouraged for this individual, whose first language is Spanish.

Discussion and Conclusion

This research aims to contribute to understanding phonetic changes during code-switching, focusing on the syllables /p/, /t/, and /k/. The findings indicate that, in addition to phonological changes influenced by language-specific properties, hyper-articulation during the experimental process can also impact the results. Notably, the VOTs of both English and Spanish were lengthened, albeit for different reasons. While previous studies suggested that English VOT should remain stable, the observed lengthening may be attributed to hyper-articulation. This phenomenon occurs when participants consciously articulate more clearly to facilitate phonetic analysis, particularly when instructed to produce distinct utterances for experimental recording. The results aligned with some of our hypotheses, though some biases were observed. Further analysis is required to identify academically sound explanations for these findings.

Due to the difference in language properties, the Spanish VOT is lengthened as predicted. Spanish generally exhibits shorter VOT than English. During code-switching between English and Spanish, the VOT of Spanish syllables was observed to be longer than that of monolingual Spanish speakers, suggesting the occurrence of phonological convergence. However, the lengthened English VOT needed to be accounted for in the hypotheses regarding phonological convergence, necessitating further exploration for alternative explanations.

Based on one of our references (Kasia Muldner,2017), English VOT during code-switching is nearly identical to monolingual speakers, which can be attributed to differences in language-specific characteristics. Consequently, English undergoes minimal phonological changes during code-switching. Our hypotheses align with previous studies, suggesting that despite minor variations, English VOT remains nearly identical to that of monolingual English speakers. However, this experiment’s data showed opposite conclusions, forging us to discover more reliable explanations.

Overall, all VOT measures, except for the Spanish /k/, did not reflect our true monolingual English and Spanish speakers. Baseline data demonstrated an increase in VOT data as the place of articulation was placed further back in the vocal cavity. The /p/ VOT was the shortest, next was /t/ VOT, and the longest was the /k/ VOT in both English and Spanish. Our participants produced a similar VOT for all the English stops (around 80 ms) and all Spanish stops (around 23 ms) These findings suggest that bilingual speakers may default to one length of VOT regardless of the place of articulation, whereas monolingual speakers produce a different VOT length for each stop consonant. Despite previous research, this provides evidence that bilinguals differ in VOT production from monolinguals.

Another interesting finding was hyper-articulation in our sample, which was characterized by more distinct and easily recognizable pronunciations. This phenomenon is hypothesized to have occurred because participants were instructed to produce clear recordings for subsequent analysis using professional phonetic tools (PRAAT), inadvertently creating a more demanding articulatory environment. Moreover, when comparing English in code-switched contexts with that of monolingual speakers, it is important to consider the inherent variations within English itself. Due to its diverse dialects and accents and a long history of linguistic contact, the definition of ‘standard’ English is ambiguous. This suggests that the participants in our study may have exhibited different English accents from the outset, potentially influencing the results of our experiment.

Our study encountered a few limitations that affected the study’s results. Firstly, it is a vital variation given that our demographic was relatively small (16 people, with 14 college students), which may produce bias. Furthermore, all of them are self-reported bilinguals, even though with a linguistic background questionnaire, the clarification of “bilingual” remained unclear and contained various things. Our linguistic background questionnaire cannot showcase the diversity and dynamic of bilinguals panoramically and thus may ignore some related variations in code-switching. Secondly, though being collected and quantitatively analyzed, the data per se remained unclear in its accuracy in spontaneous code-switching in natural utterances. Taken together, this research contributes to the research looking into the relationship between code-switching and phonological convergence in Spanish-English bilinguals. The observed VOT lengthening during code-switching contexts suggests a dynamic interaction between languages where bilingual transfer does not have a bidirectional relationship. Bilingual speakers may also adjust their articulation based on the contextual demands of the linguistic environment. Future studies could further explore the implications of phonological transfer and its potential effects on language production in bilinguals.

Appendix I: Linguistic background questionnaire[1] [2]

(1) Is English your L1 or L2?

(2) Is Spanish your L1 or L2?

(3) Can you read and speak Spanish?

(4) Can you read and speak English?

(5) Do you speak any other language other than English and Spanish?

(if yes, which languages?)

(6) On a scale from 1-10, how often would you say you code-switch between English and Spanish? (Code-switching is the act of alternating between two or more languages or dialects within a conversation or phrase.)

(7) How positively or negatively do you feel about speaking Spanglish?

(8) Have you ever felt discouraged from speaking Spanglish?

- yes

- no

Appendix II: The Rainbow Passage in English and Spanish

When the kind sunlight strikes cold raindrops in the air, they act as a prism and form a rainbow. El arcoiris divide la luz blanca en muchos colores hermosos. Estos toman la forma de un arco tan largo, with its path high above and its two ends apparently beyond the horizon. There is, according to legend, a boiling pot of gold at one end. People look, pero nadie lo encuentra. Cuando un hombre busca algo más allá de su alcance, sus amigos pueden decir que está buscando la olla de oro al final del arcoíris. Throughout the centuries, people have explained the rainbow in various ways.

References:

Balukas, C., & Koops, C. (2015). Spanish-English bilingual voice onset time in spontaneous code-switching. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(4), 423-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913516035

Banov, I. K. (2014, December 1). The production of voice onset time in voiceless stops by … BYU ScholarsArchive. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5339&context=etd

Castañeda Vicente, M. L. (1986). El V.O.T de las oclusivas sordas y sonoras españolas. Estudios de fonética experimental, 2, 91-110.

Kasia Muldner, Leah Hoiting, Leyna Sanger, Lev Blumenfeld and Ida Toivonen.The phonetics of code-switched vowels, Carleton University, Canada https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1367006917709093

Lisker, L., & Abramson, A. S. (1964). A Cross-Language Study of Voicing in Initial Stops: Acoustical Measurements. WORD, 20(3), 384–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1964.11659830

Ojeda, Adriana, Ana De Prada Pérez, and Ratree Wayland. Heritage Speakers and their Language Use: A Phonetic Approach to Code-Switching. University of Florida.

Olson, D. J. (2016). The role of code-switching and language context in bilingual phonetic transfer. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 46(3), 263–285. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26352311

Piccinini, P., & Arvaniti, A. (2015). Voice onset time in Spanish–English spontaneous code-switching. Journal of Phonetics, 52(Sep), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2015.07.004 Voice onset time. (n.d.). ScienceDirect. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/voice-onset-time