Izze Castillo, Sophia Le, Simon Oh, Kenneth Tran, Bryan Nguyen

Just died in a game? What’s the first word that comes out of your mouth? This study examines gender-based differences in profanity use among popular gaming streamers to explore how digital platforms reflect and reinforce societal norms related to language and gender.

Existing literature indicates that men generally use profanity more frequently and with greater intensity than women, and that such behavior is often socially accepted or even valorized in men while criticized in women (Bailey & Timm, 1976). Drawing on prior sociolinguistic and gender communication research, this study analyzes the speech patterns of eight prominent male and female streamers, focusing on the frequency, direction, intensity, tone, function, and contextual usage of expletives during gameplay. We hypothesize that men will use direct profanity at a higher frequency, intensity, and variety, using it to express anger and dominance during gameplay, whereas women will use milder swear words at a lower frequency to be more emotionally expressive and maintain relationships. By identifying patterns in swearing behavior across genders in streaming contexts, we can understand how gendered language norms exist and change in online environments.

Introduction and Background

Gamers have become a major source of online entertainment. They are especially popular among younger generations, who see them as more relatable and authentic than traditional celebrities. Profanity is everywhere in streaming but it’s not treated the same across genders. Male streamers are often seen as funny and entertaining when they swear, compared to females who are seen as rude or inappropriate.

Existing studies comparing the swearing differences between male and females have found that men typically use more intense swear words, swear more in public, and have a larger profanity lexicon than women (Bailey and Timm, 1976). Regarding public perception, men find women who swear less attractive while women find men who swear more attractive (O’neil, 2001). These findings point to gender norms in that cursing is associated with dominance and masculinity. Women who curse may be perceived as deviating from these norms and face more intolerance towards their speech patterns (Lakoff, 1972). Interestingly enough, recent studies have shown that women do not curse drastically less than men, as the rise of social media has increased the swearing rates of younger generations of women (Tikile and Ngulube, 2025). While most studies cover general gendered swearing patterns, we are interested in examining swearing patterns in streaming contexts and if societal gender norms are still enforced on digital platforms. In our study, we analyze the top gaming streamers by analyzing their swearing patterns, identifying trends regarding their speech.

Methods

To explore swearing patterns used in live-streaming environments, our group focused on a select group of popular Twitch streamers: Kai Cenat, Ninja, Caseoh, Jynxzi, Pokimane, Valkyrie, Loserfruit, and Kyedae. They all had at least a million followers and ten million hours of watched content. The streamers also played the shooter games such as Fortnite, Valorant, and PUBG, where entertaining viewers and performing well simultaneously is a key part of their content. We observed how the streamers communicated in various situations, such as under pressure, intense gameplay, moments of frustration, joking with friends and viewers, or reacting to unexpected events of the game.

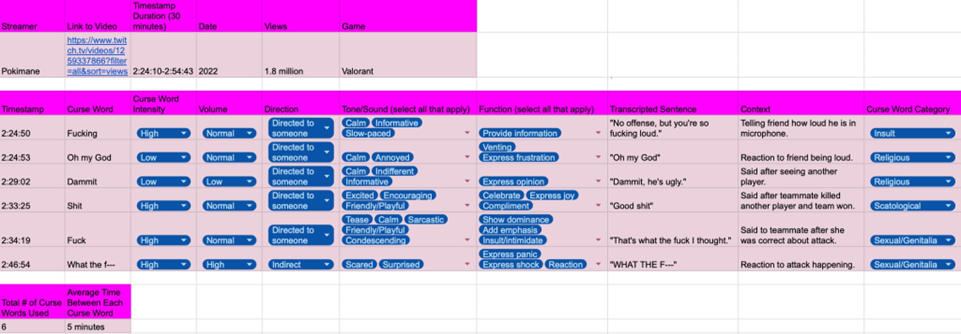

In a chart, we documented every instance of a curse word within a thirty minute streaming segment and noted its different features. For example, we noted specific profanity used and its intensity. We also observed who or what the curse word was directed to (e.g., the game, the gamer, another player, general conversation, etc.). We noted the volume and tone in which the profanity was delivered (e.g., excited, frustrated, surprised, calm). We also categorized each curse word by type (e.g., sexual, scatological, religious, slur, expletive) and documented the context as well as transcripted sentence in which the word was used. Finally, we noted the function of swearing, such as expressing frustration after dying in the game, emphasizing excitement or disbelief, or entertaining the audience. All data was recorded manually in a spreadsheet where each member documented the curse word and selected tags that applied to the word. Each streamer was viewed twice by members which allowed us to cross-reference observations and resolve disputes in different interpretations of the data, ensuring accuracy and consistency. In the end, we tallied the total number of curse words used in the segment as well as the average time between each curse word for each streamer.

Figure 1: Data collection chart for cursing behavior of streamer “Pokimane” with tags selected for each feature of curse word.

Results and Analysis

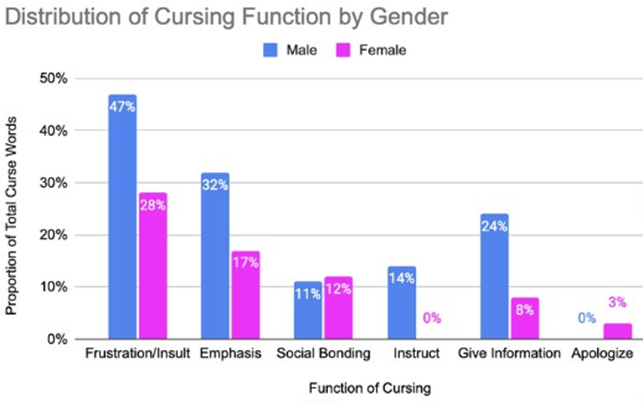

Figure 2: Bar chart showing distribution of cursing functions between male and female streamers in proportion of total curse words.

Our analysis reveals that there are distinct gender-based differences in both frequency and function of cursing across male and female streamers. For male streamers, their overall

frequency was much higher than female streamers with 85 total instances compared to 36 instances for women. For the function of cursing, we can see in Figure 2 how male streamers mostly employed it as a way to express frustration or insult 47% of the time and emphasize 32% of the time. In contrast, female streamers used cursing for those functions 28% and 17% of the time, respectively. Male streamers used curse words to instruct 14% of the time while women never used it for that purpose. Conversely, women used cursing to apologize 3% of the time while men never used it for that purpose. This may suggest that women tended to be less confrontational and more intentional with the way they relationally used profane language.

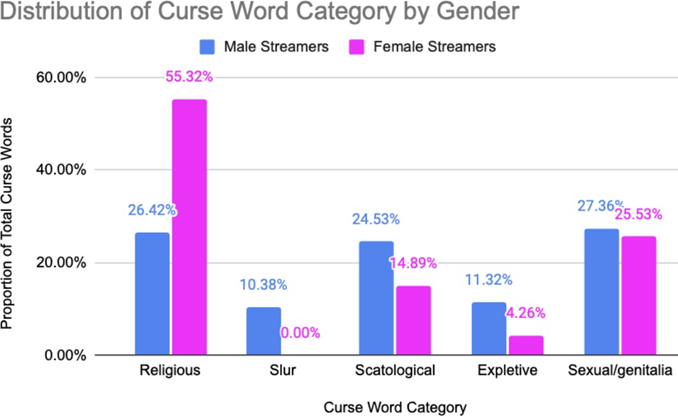

Figure 3: Bar chart showing distribution of curse word categories between male and female streamers in proportion of total curse words.

As far as the type of curse words in Figure 3, female streamers overwhelmingly favored milder, religious profanity, accounting for over half of their total curse words at 55.32%. Male streamers, on the other hand, displayed a broader distribution of slurs (10.38%), scatological terms

(24.53%), and sexual language (27.36%), suggesting their appeal for more intense profanity. This may highlight how male streamers may feel more dominant or accepted by other men, especially in their community, if they adopt the “Boys will be boys!” mentality and incorporate more sexual and derogatory forms of profanity. Women, conversely, must make up for their use of profanity by catering towards less offensive forms and abide by social conventions.

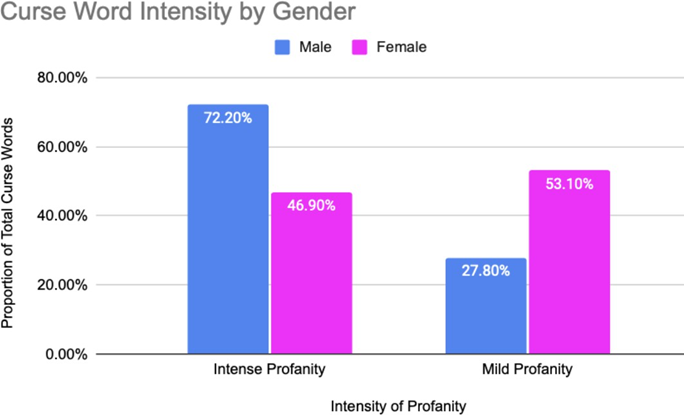

Figure 4: Bar chart showing distribution of cursing intensity between male and female streamers in proportion of total curse words.

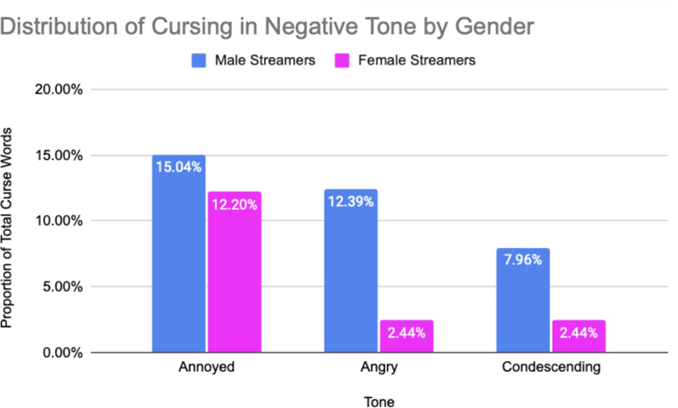

Figure 5: Bar chart showing distribution of cursing in negative tones between male and female streamers in proportion of total curse words.

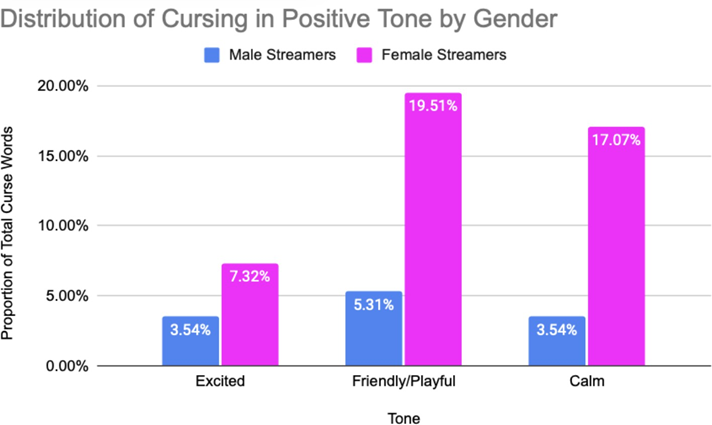

Figure 6: Bar chart showing distribution of cursing in positive tones between male and female streamers in proportion of total curse words.

Lastly, in examining emotional tone, we found that men were more likely to curse in a negative tone, such as sounding annoyed (15%), angry (12%), or condescending (8%). Women were more likely to curse in positive tones, such as friendly/playful (20%), calm (17%), and excited (17%). For the angry and condescending tone in Figure 5, we can see a drastic difference between how much men employed these tones compared to women, who used them just 2% of the time. In Figure 6, this pattern is reversed for positive tones in that women embodied this attitude at a significantly higher rate than men, who only used it 3-5% of the time. These findings suggest that profanity use is not just a matter of vocabulary, but reflects deeper gender communication norms. Male streamers tend to use curse words to assert dominance, frustration, or authority, often paired more intense and negative emotional tones. Women, however, employ profanity more creatively or socially to integrate it into positive and affiliative expressions. This gendered contrast highlights how language, even profanity, is shaped by broader patterns of social behavior, emotional expression, and interactional goals.

Discussion and Conclusion

All in all, our hypothesis was supported in that men used direct profanity at a higher frequency and intensity to express anger, while women used it at a milder, lower frequency to maintain relationships. We can see how both male and female cursing patterns reflect broader gender norms as communication is shaped by culture and societal pressures, even in digital spaces. Men employ profanity to express masculinity, dominance, and intimidation, while women tend to conform to their expectation of maintaining proper, socially acceptable behavior by regulating their profanity to build rapport. This reflects their subordinate, emotionally sensitive role compared to males as they may feel moderating language helps them remain approachable and likable. Previous studies support these findings such as Coates (2015) and Lakoff (1975) in highlighting women’s adherence to cautious, civil behavior in public settings.

Men may not have this capability to regulate emotions as well as they are more aggressive and their brains simply do not have the potential to cope with intense emotions as well as female brains (Güvendir, 2015). This biological basis has shaped gender roles in determining what communication patterns are appropriate for each gender and therefore dictates how people perceive those who conform and deviate from such conventions. Audiences may not receive female cursing as well as male cursing as it’s unconventional for females to use harsh language, prompting a more restrained, lighthearted usage in fear of judgment. Males, however, may be perceived as powerful and admirable in establishing dominance, allowing for more frequent cursing. As gaming is a rapidly evolving environment, it’s important for streamers to recognize these norms and understand the differences in audience perception. Streamers must navigate challenges in maintaining authentic personas and simultaneously conform to gender expectations to resonate and attract viewers that will appropriately receive their content and language style.

References

Bailey, L. A., & Timm, L. A. (1976). More on Women’s — and Men’s — Expletives. Anthropological Linguistics, 18(9), 438–449. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30027592.

Coates, J. (2015). Women, Men and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315645612.

Güvendir, Emre. (2015). Why are males inclined to use strong swear words more than females? An evolutionary explanation based on male intergroup aggressiveness. Language Sciences, 50, 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2015.02.003.

Lakoff, R. T. (1975). Language and woman’s place. Harper & Row.

O’neil, Robert Paul. (2001). Sexual Profanity and Interpersonal Judgement. LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/427.

Tikile, E. A., Ngulube, I. E. (2025), The Usage of Swear Words Among Generations X, Y and Z in Rivers State University. International Journal of Literature, Language and Linguistics 8(1), 37-49. 10.52589/IJLLL-7YPDRYKS.