Cia Evangelino, Saffiya Haque, Allie Kuo, Emma Montilla, Renee Rubanowitz

In music, switching between languages isn’t just linguistic— it’s poetic. Spanglish is in the studio, and it’s topping the charts. This study explores how bilingual artistry harnesses code-switching as a creative tool as it reshapes the landscape of contemporary music.

Code-switching typically signals affiliation or belonging in a community or conveys language-specific ideas, but it evolves into a deliberate stylistic choice in music and art. However, does creative liberty coincide with linguistic constraints? Our research investigates whether song lyrics, as a form of poetry, prioritize meaning over grammatical perseverance.

This article examines how bilingual artists implement code-switching into their lyrics, analyzing their use of borrowing and blending through the lens of Code Copying Framework and Poplack’s constraints.

We focused on the bilingual lyrics of Rosalía and Kali Uchis, two Spanish-language musicians with distinct bilingual backgrounds. Our analysis revealed that Rosalía, as an L2 English speaker, predominantly uses shorter borrowings and code copies to preserve English-specific semantic nuances, often refraining from full code-switching. In contrast, Kali Uchis, a simultaneous English-Spanish bilingual, employs/favors longer, fluid borrowings at clausal boundaries, seamlessly switching between two languages line by line. We hypothesize that these differences in their approach to bilingual lyricism come from their dominant language preferences and differing linguistic proficiencies.

Introduction and Background

In today’s world, bilingual music is a new and exciting way for artists to express their identity and connect with different groups of people. Look at Rosalía or Kali Uchis, for example: they both switch seamlessly from Spanish to English, often in the middle of their lyrics. What’s really happening when these artists switch languages so effortlessly? Is it just a trendy way to mix things up, or is more happening beneath the surface?

This blog delves into how bilingual artists navigate the linguistic restrictions surrounding code-switching in music. We will test if certain constraints governing spoken Spanish and English also apply in a musical context. Specifically, we will look at whether Johanson’s (2011) code copying framework and Poplack’s constraints (1980) still hold up in a lyrical format.

To understand what happens when bilingual artists code-switch in their lyrics, it helps first to unpack what code-switching is. Code-switching occurs when a speaker alternates between two languages within or between sentences. For example, Kali Uchis has a song lyric that goes, “That’s the only thing que me da alegría,” which means “That’s the only thing that brings me joy.” Here, she casually switches from English to Spanish mid-song.

According to Poplack (1980), there are some crucial grammatical constraints that bilinguals tend to follow when switching between languages, including the free morpheme constraint, which suggests that bilinguals are more likely to switch languages when one of the languages is a free morpheme. This helps to ensure that the switch does not disrupt the sentence’s grammatical structure. However, Timm (1975) argues that not all code-switching follows strict rules. Some switches and combinations of words may sound ungrammatical to bilingual speakers. Timm states that bilinguals make code-switching decisions based on the context and what feels natural in the conversation. In other words, code-switching is as much about communication goals and cultural expression as it is about grammar. However, there is another layer to all this, which is that of music. Lyrics are more than just spoken language; they are a form of artistic expression, so they have more leeway to break the “rules” of language and grammar regarding creativity. In music, artists like Rosalía and Kali Uchis often code-switch between English and Spanish to communicate and express their identity, emotions, and cultural background. In this context, code-switching may not always conform to the strict linguistic rules established by Poplack and others. These two artists’ flexibility in language reflects their different bilingual experiences and how they shape how they mesh languages in their songs.

Methods

To understand and answer our research question, we analyzed the lyrics of two prominent Spanish-English artists, Rosalía and Kali Uchis. We chose these two artists for their unique linguistic and cultural backgrounds and active use of code- and language-switching in their music. In terms of similarities, both artists are of a similar age and release Latin/Spanish music of similar genres. We thought this genre of music in particular, would be insightful to focus on, as the informality and structure of their song lyrics are a contrast from previous code-switching examples we have looked at through this course. Both women have also each built an alternative, trend-setting brand image and self-identities that hinge largely on themes of confidence, sex positivity, femininity, and empowerment.

Rosalia, photo via Europa Press News Kali Uchis, photo via Felipe Q Noguiera

Beyond these similarities that allow for standardization of our data collection, we chose Rosalía and Kali Uchis because they also represent two distinct types of bilingualism and cultural experiences, providing a rich contrast for analysis. Rosalía, born in Catalonia, Spain, is a sequential bilingual who grew up speaking Spanish and Catalan as her native languages before learning English later in life — we categorized her as an L2 English speaker. While she began her music career with a strong focus on Flamenco and traditional Spanish music, Rosalía recently transitioned into Latin and alternative reggaetón-inspired pop. Kali Uchis, in contrast, is a simultaneous bilingual born in the United States to Colombian parents. Growing up, she was exposed to both Spanish and English equally, having spent significant time in both Virginia, USA and Colombia. This dual-culture childhood is reflected in the blending of the two languages in her songs. Her discography began predominantly in English but has recently shifted to more Latin music. By examining these two artists, we hoped to explore how their bilingual backgrounds shape their distinct approaches to code-switching and linguistic creativity and how their different upbringings may have manifested themselves into their music.

We collected data by identifying ten songs from each of these two artists. We used the metric of the number of Spotify streams per song to choose their most popular music. In our data filtering, we only ensured to include tracks where the artists held writing credits, as this guaranteed that the observed code-switching and linguistic patterns came directly from their creative process rather than external songwriters that we would not know their linguistics backgrounds. Because of this in mind, we chose to include collaborations and feature songs, such as New Woman (LISA feat. Rosalía) and SI NO ES CONTIGO – REMIX (Cris Mj feat. Kali Uchis & JHAYCO), as these song features tended to be 1) highly streamed, and 2) written by the artists themselves. Then, to narrow our focus to bilingualism in music, we excluded songs entirely in Spanish or English, as these songs were not tailored to our interests and would not illustrate instances of bilingual code-switching. Lyrics were sourced from Genius, a widely used database for accurate song transcription, translations from the Genius community comments, or from members of our group who are beginning L2 Spanish speakers.

Example of songs taken from Rosalia’s Spotify artist profile, including streams

After selecting 23 songs for our dataset, we parsed each song, compiling lines of lyrics in which a language switch occurred. To identify these switches, we applied the established definitions of intra- and inter-sentential switching and the structure of the code-copying framework. These lyrics were documented and later analyzed on a robust spreadsheet.

| Song Selection Data Samples | |

| Kali Uchis | |

| Song: SAD GIRLZ LUV MONEY Remix – Feature 2021 Release 461.5m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: Yeah, you’ve been starin’ at me (¿Por qué me miras?) That’s the only thing que me da alegría Yo quiero sentirte inside of me |

| Song: Moonlight 2023 Release 829.8m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: I just wanna get high with my lover, Veo una muñeca cuando miro en el espejo |

| Song: telepatía 2020 Release | Lyric: If you want it, you could take a private plane, a kilómetros estamos conectando |

| 1.2b Approx. Spotify Streams | Y me prendes aunque no me estés tocando |

| Song: Igual Que Un Angel 2024 Release 332m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: You should’ve seen the way she looked, igual que un angel Heaven’s her residence y ella no se va a caer |

| Rosalia | |

| Song: Despecha 2022 Release 1.1b Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: Hoy salgo con mi baby de la disco corona, corona, yeah |

| Song: New Woman – Feature 2024 Release 223m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: Puta, soy la Rosalía, solo sé servir |

| Song: TKN 2020 Release 465m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: Zoom en la cara, Gaspar Noe |

| Song: Besos Moja2 2022 Release 442.6m Approx. Spotify Streams | Lyric: To’ me queda bien con una white tee To’ me quieren casar, soy una wifey |

Results and Analysis

In total, we collected data from 23 different songs released between 2019 and 2024, with 10 being songs by or featuring Rosalía and 13 by or featuring Kali Uchis. From these 23 songs, we extracted 19 (38.7% of data) data samples from Rosalía and 30 (61%) data samples from Kali Uchis – resulting in 49 data samples. Generally, most code-switching occurs as an intersentential switch, which means it happens at clausal boundaries between sentences instead of within a sentence.

The results we discovered while gathering our data prove some interesting differences between how sequential and simultaneous bilinguals code-switch. For example, Rosalía, a sequential bilingual who primarily makes her music in Spanish within the Flamenco musical style, is more likely to code switch in her music when in the Latin context or if she appears as a feature on songs with Latin artists. Meanwhile, Kali Uchis, a simultaneous bilingual, is more likely to code-switch in her music in general. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, we could not investigate how heavy of a correlation each artist’s background influences their code-switching/code-coping tendencies. Still, based on the data, we can tell each artist has a preference on how bilingualism is written into their music. We expected a vast majority of code copying to occur within our data. Still, only 40.8% of data resulted from code-copying versus code-switching, with an overwhelming majority of code-copying data samples from Rosalía (80% of code-copying samples). Comparatively, Kali Uchis heavily favors code-switching, with 80% of her data samples containing some form of code-switching. She tends to favor longer phrases of code-switching instead of single-word copies. The data table below shows examples of the different types of code-copying occurring with a song from each artist.

| Song Lyric Data Analysis Samples | ||

| Igual Que Un Angel – Kali Uchis Kali Uchis, Peso Pluma – Igual Que Un Ángel 0:20-0:30 | ||

| Lyric: You should’ve seen the way she looked, igual que un angel Heaven’s her residence y ella no se va a caer | Translation: You should’ve seen the way she looked like an angel Heaven’s her residence and she’s not gonna fall | Analysis: Selective copying: igual que un angel mirrors the English structure to retain meaning while adapting to Spanish syntax |

| fue mejor – Kali Uchis Kali Uchis – fue mejor feat. SZA 1:00-1:10 | ||

| Lyric: Y me fui en el Jeep a las doce The backseat donde yo te conocí | Translation: And I left in the Jeep at twelve The backseat where I met you | Analysis: Global copy example: “Jeep” and “the backseat” are English words with all properties preserved and integrated into the lyrics |

| Besos Moja2 – Rosalia | ||

| Wisin & Yandel, ROSALÍA – Besos Moja2 2:22-2:33 | ||

| Lyric: To’ me queda bien con una white tee To’ me quieren casar, soy una wifey | Translation: It looks good on me with a white tee They all want to marry me, I’m a wifey | Analysis: Global copying: the English phrases white tee and wifey are borrowed intact and function within the Spanish sentences without alteration |

| New Woman – Lisa feat. Rosalia LISA – NEW WOMAN feat. Rosalía 1:48 – 1:52 | ||

| Lyric: Puta, soy la Rosalía, solo sé servir | Translation: Bitch, I’m Rosalía, all I do is serve | Analysis: Selective copy example: semantic meaning of “serve” is preserved, directly translated from English to Spanish |

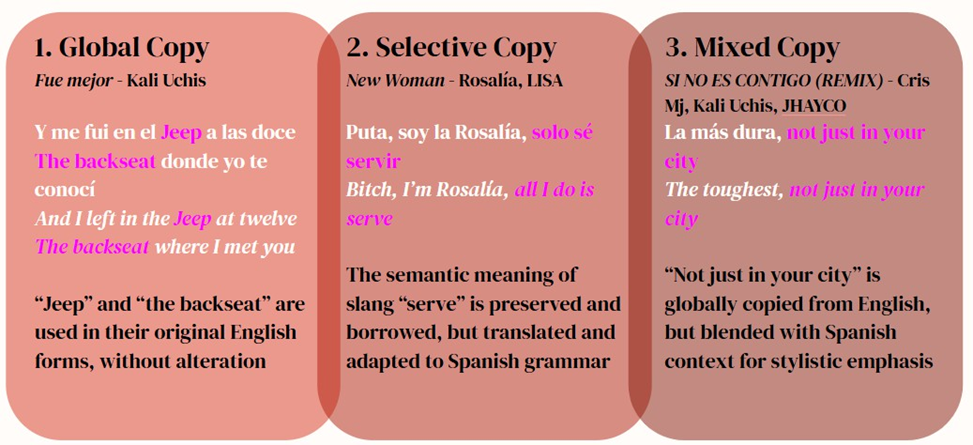

The types of copying that we came across in our data are:

- Global copies (taking words in their unaltered form and using them within a sentence).

- Selective copies (the structure of a word or phrase is kept while adapting to another language’s syntax).

- Mixed copies (switching between one language to another within a sentence or phrase). From our data, a majority of the data uses mixed copying, accounting for 40% of the examples. Global copying accounted for 36% of our data, while selective copying accounted for 16%.

Discussion and Conclusion

From our corpus of lyrics, we concluded that code-switching in music tends to deviate from standard grammatical constraints and, therefore, does not strictly follow Poplack’s Constraints. Instead, code-switching in music more closely aligns with and reflects the artists’ bilingual background. Rosalía, a sequential bilingual, is more deliberate in her switches when using English in songs to identify specific concepts like “wifey” or “to serve.” On the other hand, Kali Uchis, a simultaneous bilingual, is more spontaneous in her use of code-switching; her fluidity between Spanish and English is representative of the dual integration of both languages in her identity. Still, we observed both global and selective copying in the artists’ lyrics and could conclude that global and selective copying are common and focal aspects of bilingual lyricism.

Nonetheless, we acknowledge the limitations of our investigation. Due to the temporal constraints of the quarter system, our project timeline was very restricted, and we could not expand the scope of our exploration and means of data collection. Thus, our focus on two artists and reliance on public information could have been a more comprehensive elicitation of analyses.

Revisiting our initial research questions: If certain constraints apply in spoken Spanish when code-switching to English, do they transfer over the same way into language in a musical context? What types of copying, following the code copying framework, will be found in song lyrics?

The integration of multiple languages in music has far-reaching implications for linguistic research, cultural understanding, and artistic expression. Understanding code-switching in creative language use provides insights into how language patterns manifest in nontraditional language contexts, namely under the influence of the artistic nature of lyricism and songwriting. Code-switching in music also enhances artistic expression by encouraging dynamic wordplay and rhymes across languages. It provides insights into the differences between different levels of bilingualism and types of multilingualism. Moreover, bilingual lyrics serve important cultural functions, as they represent the juxtaposition of cultures, promoting linguistic and cultural diversity, expressions, and communication. Within the music industry, multilingual music can unite different listeners’ cultures and expand the reach of artist audiences.

Although our research yields valuable insights, it needs to be more broadly generalizable to all Spanish-English or other language bilingual musicians. Future expansions of our study will include a larger sample of bilingual artists with a more extensive range of lyrical repertories from more diverse language backgrounds. It would be ideal to have direct access to artists’ accounts of their language to better understand their use and relationship with their respective languages as well as their creative processes.

An important consideration to account for in our investigation is the existence of code-switching patterns for Spanglish that do not necessarily apply to varieties of Iberian Spanish. The present investigation focused primarily on code-switching conventions within a musical genre rather than a dialect, assuming that an artist from Spain would adapt to Latin American dialectal features in this context, but dialectal differences may still occur. We are interested in understanding competing factors of bilingual acquisition and regional norms to further develop our research from this investigation, specifically, the influences of sequential and simultaneous bilingualism and regional norms for language in Latin American versus peninsular Spanish varieties. Additional research directions would look across different genres and investigate the reception of code-switched lyrics among monolingual and bilingual listeners, considering the linguistic influence of lyricism more broadly in language communities.

References

Cris MJ, Kali Uchis & JHAYCO – Si No Es Contigo (remix). Genius. (n.d.-a). https://genius.com/Cris-mj-kali-uchis-and-jhayco-si-no-es-contigo-remix-lyrics

Duran, R. P. (1984). Latino Language and Communicative Behavior. The Modern Language Journal. Exposito, Suzy. “Pop Loner Kali Uchis on Growing up Punk in Colombia and the Struggle to Stay Bilingual.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 13 Sept. 2019, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-latin/kali-uchis-isolation-colombia-interview-2018-7 00772/.

Gonzalez-Cruz, M. I. (2017). Exploring the dynamics of English/Spanish codeswitching in a written corpus. Alicante Journal of English Studies, 30 (2017), 336-361.

Johanson, L. (2011). Contact-induced change in a code-copying framework.

Lisa (ft. Rosalía) – New Woman. Genius. (n.d.). https://genius.com/Lisa-new-woman-lyrics Lipski, J. M. (2008). Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Georgetown University Press.

Loaiza, K. M. “Kali Uchis”. Lyrics to “ORQUÍDEAS” [Album]. Geffen Records, 2024. Genius, genius.com/albums/Kali-uchis/Orquideas.

Monteagudo, M. (2020). Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception. https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/79796

Poplack, S. (1980). Sometimes, I’ll start a sentence in Spanish Y TERMINO EN ESPAÑOL: toward a typology of code-switching1. Linguistics, 18(7-8), 581-618. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1980.18.7-8.581

Sayre, A. A. (2022). “Rosalia is unafraid to pull from every corner of the world.” NPR, NPR, 24 April 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/04/24/1094491641/rosalia-is-unafraid-to-pull-from-every-corn er-of-the-world

Timm, L. A. (1975). Spanish-English Code-Switching: El Porqué y How-Not-To. Romance Philology, 28(4), 473–482. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44941606

Villa Tobella, R. ‘ROSALÍA’. Lyrics to “Motomami” [Album]. Columbia Records and Sony Music, 2022. Genius, genius.com/albums/Rosalia/Motomami.

Rosalía. (2022). Motomami [Album]. Columbia Records. Uchis, K. (2024). Orquideas [Album]. Geffen Records. Uchis, K, and SZA. “Fue Mejor.” Genius, Genius Media Group, n.d., https://genius.com/Kali-uchis-and-sza-fue-mejor-lyrics