Why is it that two presidents talking about the same issue can make it feel like we’re living in two completely different countries? This project analyses how President Trump and former President Biden rhetorically frame the issue of abortion. To one, abortion is about individual freedoms, rights and democratic choices, while to the other it is about morals, faith and American values. Focusing on six speeches, three per leader, that were presented between 2020 and 2024, we conducted a discourse analysis and focused on rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, logos), tone, emotional triggers and opposition framing. We found that President Trump tends to frame the issue as a moral crisis whereas Former President Biden tends to frame it as a constitutional one. Former President Biden tends to use double the (average) number of rhetorical appeals when compared to President Trump, however they both tend to refer to each other/the opposition almost the same amount. These patterns showed us how political speech is tailored not only be informative, but also to shape public opinion, showing how the rhetoric used can perpetuate a specific narrative and benefit the politician.

Introduction and Background

Persuasive rhetoric around the topic of abortion varies greatly between people, in this case, the variation addressed will be that of two prominent political figures: President Trump and Former President Biden, both of whom use persuasive rhetoric to influence people’s opinions greatly, but differ greatly in how they address the public. While the initial objective of their statements may be to inform, they also work to persuade public opinion on various subjects in hopes to garner more voter support and donations.

There is a plethora of research analyzing how political leaders use persuasive rhetoric, particularly framing, emotional appeals, and identity-based language to shape public understanding of controversial ideas. Scholars like Lakoff (2004) have demonstrated how metaphors and framing have influenced voter perception around cultural topics. Similarly, scholars like Jamieson and Campbell (2001) have analyzed how presidential rhetoric uses pathos, ethos, and logos to construct political narratives. This tendency is consistent with Homolar and Scholz’s (2019) analysis of 74 Trump campaign speeches, which shows that crisis-laden, us-versus-them narratives create ontological insecurity and mobilize voter support.

In reference to reproductive rights, scholars like Medved and Rawlines (2000) and Ginsburg (1989) have explored how abortion is framed through competing moral, legal, and religious lenses. However, we have noticed a significant gap in recent work that compares the persuasive rhetorical strategies of former President Biden and President Trump specifically within the context of abortion rights.

Our objective was to fill that gap by asking: How do former President Biden and President Trump use persuasive language to frame abortion, and is it done emotionally, logically and/or by establishing their credibility to their audience? We wanted to understand how social identity and ideology can affect political communication, especially around issues as heavily debated as abortion.

Methods

We selected six public statements, three from each leader, delivered between 2020 and 2024. They were a mix of addresses, campaign speeches, and national statements.

Biden:

- National address on the Dobbs decision (June 24, 2022)

- Democratic National Committee speech on codifying Roe (October 18, 2022)

- State of the Union (March 7, 2024)

Trump:

- March for Life rally address (January 24, 2020)

- Fox News interview responding to Dobbs (June 24, 2022)

- Formal policy statement on abortion exceptions (April 8, 2024)

While the setting and occasion of each speech varied, we did not find a difference in the rhetorical strategies used across formats. This allowed for us to compare content collectively; we performed a manual discourse analysis focusing on three rhetorical appeals: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic) as described in Aristotelian rhetorical theory (Crowley & Hawhee, 2004). To code our data, we utilized a coding framework adapted from established methods in political communication research (Jamieson & Campbell, 2001; Charteris-Black 2014). Emotional appeals like personal stories or dramatic metaphors were marked as pathos while references to values or identity and personal experiences were considered ethos. We marked statements as logos if they were factual claims including a reference to the law or cause-and-effect reasoning. We proceeded to also look at how often they used these and the tone they employed when referring to their opposition. Once we had all of this information, we took the averages of the total numbers we were able to tally from observing ethos, pathos, and logos to compare which president uses rhetorical appeals more, or if one of them uses a specific rhetorical feature more than the other. Observing each candidate’s tone also played a key role in this analysis. We also counted how many times each candidate mentioned the other, whether negative or positive, in order to determine if one side mentioned the other more or not and try to see if that potential imbalance could tell us something about their overall persuasion style and technique.

Here are some examples of statements we heard:

Biden:

- “And it was a constitutional principle upheld by justices appointed by Democrat and Republican Presidents alike.”

- “The only sure way to protect a woman’s right to choose is for Congress to restore the protections of Roe v. Wade as federal law.”

- “I grew up in a home where not a lot trickled down on my dad’s kitchen table.”

Trump:

- “They are coming after me because I’m fighting for you”

- “You know, it’s about helping women, not hurting women”

- “Follow your heart, your religion, your faith,”

Results and Analysis

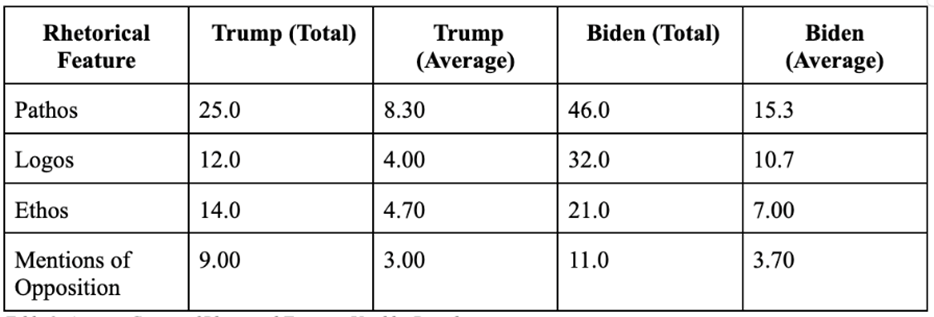

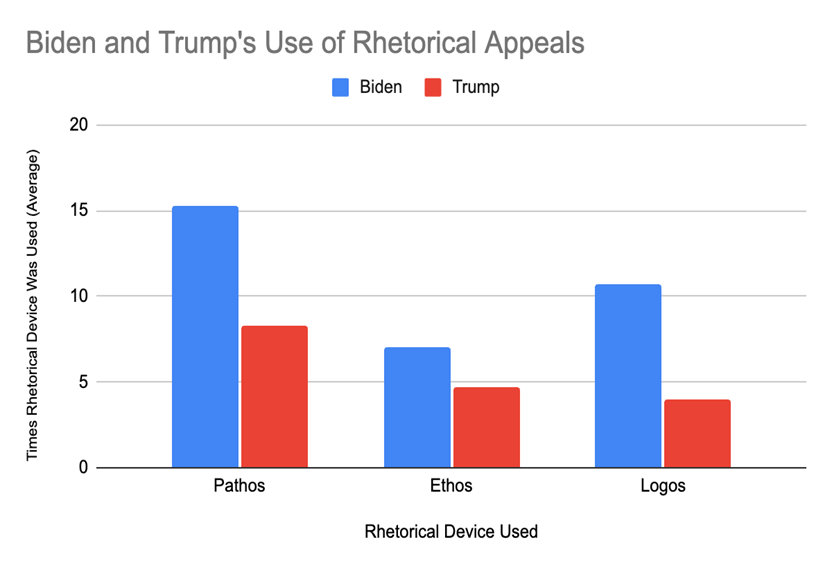

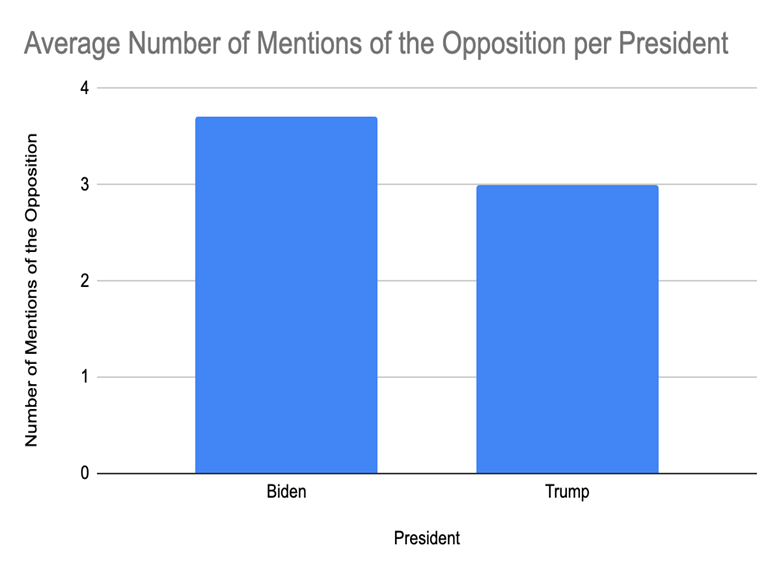

To analyze the information, we decided to summarize our results and convert them into tabs, color-coded schemes, and some bar charts so that our data would be easily recognizable for a non-initiated reader who wants to learn about the topic quickly. Our results found that in total, both President Trump and former President Biden used the most Pathos to connect with the emotions of their audience. However, former President Biden used it a total of 46 times whereas President Trump used it 25 times overall. This shows that former President Biden focuses more on appealing to the heart strings of his viewers. They both used mentions of opposition the least, making us believe that it did not affect either of their persuasion levels, since. In terms of ethos, pathos, and logos, President Trump used logos the least in total while Former President Biden used ethos the least in total but used all rhetorical features more than President Trump. This shows that Former President Biden relied more on legal or statistics-based reasoning (logos), whereas President Trump relied relatively more on personal credibility claims (ethos).

Table 1: Frequency of Rhetorical Features in Each President’s Speeches

Let’s Visualize It

Figure 1: Average Count of Rhetorical Device Use by Presidents

Figure 2: Bar Chart Showing Average Count of Opposition Mentions Used by Presidents

Discussion and Conclusion

Two takeaways from the results that are key factors in persuasion. First, both Presidents work the emotional angle, but Former President Biden does it twice as often as President Trump. Former President Biden speaks about kitchen-table stories and urgent pleas to be an active participant in American society and politics. President Trump still plays on pathos, but leans harder onto credibility, posturing as a guardian of faith and tradition. Second, their styles of framing are drastically different. For example, about abortion Former President Biden frames it as rights, privacy, and the rule of law. Whereas President Trump frames it as a fight to save an innocent life granted by God. This mirrors the partisan split across the nation, liberty language on the left while the right uses language aimed at morals.

Presidential framing influences the subsequent policy discourse. When Former President Biden emphasizes congressional action, he situates the argument within formal institutional mechanisms and encourages legislative engagement. President Trump characterizes abortion as a sacred mission, which reframes the debate to a doctrinal domain that resists policy compromise. Lexical analysis supports this distinction: Former President Biden’s address contains higher frequencies of rights-oriented and procedural terms, whereas President Trump’s statements prioritize morally and religiously coded vocabulary.

Context further adjusts these strategies. President Trump’s April 2024 policy statement includes exceptions for rape, incest and maternal health, indicating a calibrated appeal to moderate audiences. Conversely, Former President Biden’s June 2022 national address following Dobbs employs predominantly legal language, reducing emotive slogans to reach a broader viewership. These variations demonstrate that rhetorical choices are audience-contingent and strategically adaptive.

This project examined six prominent speeches; therefore, generalizability is limited, and manual coding introduces potential subjectivity. Future research should analyze a larger dataset and have a predetermined coding method to validate these patterns. The observed divergences illustrate how presidential rhetoric contributes to sustained polarization in public attitudes toward any issue for which policy is being produced.

References

Biden White House, (2022) Remarks by President Biden on the Supreme Court Decision to Overturn Roe v. Wade. National Archives and Records Administration, bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/06/24/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-supreme-court-decision-to-overturn-roe-v-wade/.

Biden, J. (2024). 2024 State of The Union Address by Joe Biden. The Joe Biden Whitehouse on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFVUPAEF-sw

Charteris-Black, J. (2014). Analysing political speeches: Rhetoric, discourse and metaphor. Palgrave Macmillan.

Crowley, S., & Hawhee, D. (2004). Ancient rhetorics for contemporary students (3rd ed.). Pearson/Longman.

Ginsburg, F. (1989). Contested lives: The abortion debate in an American community. University of California Press.

Homolar, A., & Scholz, R. (2019). The power of President Trump-speak: Populist crisis narratives and ontological security. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(3), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1575796

Jamieson, K. H., & Campbell, K. K. (2001). The interplay of influence: News, advertising, politics, and the mass media (5th ed.). Wadsworth.

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t think of an elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Medved, C. E., & Rawlins, W. K. (2000). At the intersection of personal and political: Complicating abortion narratives. Women’s Studies in Communication, 23(2), 167–189.

Messerly, M., & Allison, N. (2024). Trump Says Abortion is Up to the States, Declines to Endorse National Limit, Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2024/04/08/trump-says-abortion-is-up-to-the-states-declines-to-endorse-national-limit-00151022

National Archives and Records Administration. (2020). Remarks by President Trump at the 47th Annual March for Life, National Archives and Records Administration, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-47th-annual-march-life/

Rev (2022) President Biden Addresses Democratic National Convention, https://www.rev.com/transcripts/president-biden-addresses-democratic-national-convention

TIME (2024). Read the Full Transcript of Donald Trump’s Interview with TIME, https://time.com/6972022/donald-trump-transcript-2024-election/