Jura Glennie, Ryan Gorji, Mikaela Edwards, Zahra Umar, Lizett Hernandez

Have you ever received a text that just said “okay.” and spent the next hour wondering if someone is mad at you or if you’re just being too Gen Z about it? These kinds of reactions highlight how digital communication is often interpreted through generational lenses that can drastically shift meaning and connection in digital conversations. In this study, we investigate how generational differences affect the interpretation and use of digital features in text-based interactions. The research examines how Generation X (born 1965-1980) and Generation Z (born 1997-2012) understand and express digital body language through the use of punctuation, capitalization, emojis, and acronyms. We hypothesize that Gen Z will use more expressive forms of digital body language while Gen X will favor more minimal or formal styles, since they did not grow up in the digital age. This study focuses on how these generational groups perceive emotions, the reasoning behind selected features, and relationship-based decisions in digital communication. Previous research shows that nonverbal cues were created and popularized by younger generations, making them more recognizable to Gen Z, which aligns with our study’s findings. The takeaways from our results suggest that while digital features are identifiable amongst these age groups, their generational differences shape their communication style and interpretations.

Introduction and Background

Texting has become a primary mode of interaction, and with it, a new kind of nonverbal language has emerged. As digital communication becomes more widely used to communicate, the rules for how one should interpret a text aren’t always agreed upon. Their interpretations vary due to our age and experience within our generational environments. What feels natural and obvious to one generation can feel informal, confusing, or new to another.

This study aims to investigate how two generations, Gen X and Gen Z, navigate digital body language. Our study begins by introducing digital body language (DBL), the way people subtly and non-verbally communicate and express themselves through their use of capitalization, punctuation, emojis, slang, acronyms, response times, etc., in constructing online messages (Irshad, 2024). Followed by an overview of our research methods and implementation. Then we present the key findings from the participants’ responses, highlighting generational differences in interpretation, tone, responses, and emoji usage. Finally, we review the broader implications of these different generations and discuss their ability to adapt when navigating unfamiliar digital cues and how their responses may be shaped by varying levels of cultural immersion in the digital age.

As texting has become a dominant form of communication, people have developed new ways to express tone and emotion without speaking. These include punctuation, emojis, and message interpretations, which researchers often call digital body language. While these features help fill in the gaps left by the absence of facial expressions and vocal tone, their meaning can vary depending on who is reading them.

Prior studies have shown that younger generations tend to use and interpret these digital cues differently from older ones. For example, Gen Z, who grew up immersed in texting and social media, often assigns emotional weight or social meaning to features like lowercase typing or a final period. The New York Post report noted that, to young people, “using a period in messaging now looks rather emphatic, and can come across as if you’re quite cross or annoyed” (Frishberg, 2020). For example, Gen Z, who grew up immersed in texting and social media, often assigns emotional weight or social meaning to features like lowercase typing or a final period. In contrast, Gen X may interpret the same features through a more literal lens, viewing them as grammatical or functional rather than expressive. Binghamton University psychology research found that texts ending in periods were perceived as less sincere than those without punctuation, suggesting that punctuation alone can change emotional tone (Klin, 2016).

Despite growing research in online communication and generational differences, there is still limited understanding of how digital body language is interpreted across generations in casual text exchanges. Our study focuses on this gap by comparing how Gen Z and Gen X understand and use key digital features in message-based conversations. We aim to uncover whether the same text message is read differently depending on the generation of the reader, and what this might reveal about changing norms in digital communication.

Figure 1

Generational Differences in Emoji Use and Interpretation

TikTok – Generational Emoji Usage

Note. A viral TikTok humorously captures the difference between generational interpretations of emojis. The creator of the video explains, “we really gotta teach our parents how to properly use emojis…” then shows the text he received, which said “your uncle Mark died [skull emoji]”. Gen Z often uses the skull emoji to express exaggerated reactions, humor, or sarcasm, unlike Gen X, which interprets this emoji as literal death, which contributed to the message sounding comical and inappropriate.

Figure 2

Generational Differences in Texting

YouTube Video – Texting Across Generations

Note. A snippet from a podcast episode discusses how our digital interactions are shaped by our relationships with others. One of the speakers talks about how the way she positions her digital body language depends on the person she’s texting, saying that “different people bring out different texting sides of me” (The Council, 2025). She then goes on to talk about how this switch-up is especially prevalent when she is texting members of older generations, such as her father. When messaging her father, she’s observed that their text conversations are based entirely on message content and practicality, and there’s less of an emphasis on tone and nuances.

Methods

Data was gathered from ten participants, five members of Generation X and five members of Generation Z, through semi-structured interviews. Each interview consisted of the same exact format, but was semi-structured in the way that the design encouraged follow-up questions and elaboration from interviewees. The interviews were divided into four parts: (1) demographic and technology profile, (2) message-interpretation task, (3) punctuation and capitalization, and (4) emoji-choice scenario. The first section collected basic background information, such as age, gender, and technology usage habits. The second part presented five different text messages, written by us. Each message contained one or more features of digital body language—punctuation marks, capitalization or lack thereof, emojis, and acronyms. We showed each participant these messages, one by one, and asked them what tone they perceived and how they would respond. The third exercise was also made up of messages we designed, but it focused on only punctuation and capitalization features, such as capitalizing or not capitalizing the first word of the message, capitalizing the entire message, as well as using a period, exclamation point, or no punctuation at all. It also featured three messages with the same exact word content, but two different versions of each message: Version A and Version B. What set these versions apart were their differing levels and use of punctuation and capitalization. After presenting these two different versions, we then had participants choose which version they think is friendlier and explain why. In the final section, participants were presented with eight different emojis to choose from and asked to choose which two they’d use to respond to a message from a friend announcing a new job. Once interviewees chose their top emojis, we asked them two follow-up questions, which were why they picked those emojis and if their choices would change if the message had come from an acquaintance rather than a friend. Through these interviews, we analyzed how members of these different generations interpreted and expressed various online non-verbal cues, also known as components of digital body language. We sought to identify generational differences and patterns in how each generation processed these features.

Results and Analysis

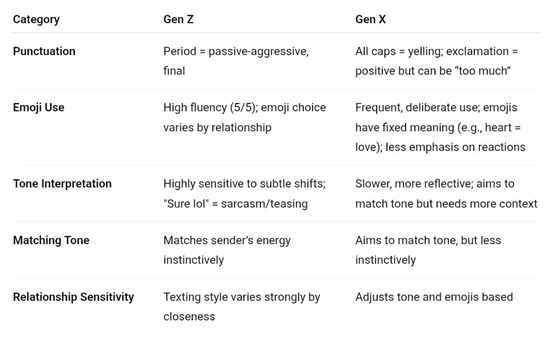

Based on what we have collected, we have obtained results that can help us make inferences out of the differences between Gen X and Gen Z. We found most importantly that in relation to punctuation and formatting, a period (e.g., “Okay.”) is interpreted as annoyance, finality, and/or passive aggression among our Gen Z interviewees. This follows our literature base where, according to Teresa Apgar, “research suggests that younger individuals interpret text-final periods to be more negative in tone, while older individuals interpret it to be neutral” (Apgar, 2022, 1). When it came to tone shift and identification, we found that Gen Z had a strong sensitivity to changes in tone, particularly when familiar contacts shift from informal to formal texting styles that are reflected in the punctuation and capitalization. Another piece of research literature that helps us understand passive-aggressivity mentioned previously is the situation where both subject Gen Z’ers are observed: “Lisa evaluates Nelly’s [non-punctuation lowercase] reaction as inappropriate by repeating her utterance and adding an iterated question mark” (Busch, 2021, 38). Conversely, lowercase messages without periods were deemed more so as friendly and casual among Gen X interviewees. Now, when it comes to emoji use and interpretation, we found that emoji choice changes depending on the relationship for Gen Z (e.g., [flame emoji] is for close friends). This relationship-dependent emoji use selection was not as prevalent in Gen X responses. We theorize that this lack of variety in emoji usage was probably due to Gen X’s simple lack of exposure time to the emoji features. See Figure 3 below.

Figure 3

Digital Communication Cue Interpretation: Gen Z vs. Gen X

Note. This chart summarizes/simplifies our results as a whole according to relevant categories (extreme left).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our exploration into generational interpretations of digital textual communication demonstrates a divide in how meaning is constructed and perceived across age groups. Through interviews with members of both Generation X and Generation Z, we observed that the tools of modern text-based communication carry different meanings depending on one’s digital fluency and cultural context.

Within Generation Z, we noticed there to be a deeper sensitivity to the emotional and social undertones of simple texting features. Even something as minute as a period at the end of a sentence could indicate a different tone or even a conflict. Generation Z interpreted texts figuratively and consistently attempted to read between the lines.

Contrastingly, Generation X looked at the texts in a more literal and formal light. Punctuation was used for the purpose of grammar, and emojis were viewed straightforwardly with little subtext. Some members were aware of the subtext, but did not spot it as consistently as their Gen Z counterparts.

A key insight of our study is that, while members of both generations utilize and recognize non-verbal cues in text, Gen Z appears to have developed a more nuanced form of digital literacy. Their fluency allows them to read undertones that older generations would not as easily detect, which may allow them to engage in complex, layered conversations entirely through digital platforms, where meaning is often conveyed as much by how something is said as by what is said.

As digital communication keeps evolving, the language and meaning embedded within it follow. Our findings suggest that generational gaps in digital interpretation are not just a result of age, but additionally, cultural immersion. Many members of Generation Z grew up using computers, tablets, and phones, where communication was quite text-heavy and rich with emoji use. Generation X was not introduced to the same kind of communication until their adult lives; they are perfectly capable of adapting, but the trend for this group is to interpret digital language through a more traditional, literal lens.

References

Apgar, C. T. (2022). Wait wdym?: Examining the (mis)perception of emotional valence in text messaging across generations (B.Phil. thesis, University of Pittsburgh). University of Pittsburgh.

Busch, F. (2021). The interactional principle in digital punctuation. Discourse, Context & Media, 40, 100481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100481

Danger. [@natedanger]. (2021, April 2). Rip uncle mark #family #emoji #fyp [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZP8MEvPnM

Frishberg, H. (2020). Young people don’t trust anyone who uses this punctuation mark. (2020, August 24). New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/08/24/young-people-dont-trust-anyone-who-use-this-punctuation-mark/

Irshad, S. (2024). Deciphering digital body language and the Gen-Z in new normal. Creative Saplings 2(10), 31-41. https://creativesaplings.in/index.php/1/article/view/498

Klin, C. (2016, June 12). Study: Punctuation in text messages helps replace cues found in face-to-face conversations. Binghamton University News. https://www.binghamton.edu/news/story/873/study-punctuation-in-text-messages-helps-replace-cues-found-in-face-to-face

The Council. (2025, January 31). Texting across generations: The surprising differences [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcC5_VWPf4U