Hannah Chu, Trevor Htoon, Youchuan (Aaron) Hu, Ann Mayor, Grace Yao

Can we detect language change right as it’s happening? As a result of nearly a century of colonial handoffs, the Southeast Asian Island of Singapore developed its own, unique variety of English: Singapore Colloquial English, more commonly known as Singlish. There is reason to hypothesize, though, that Singlish may be progressively becoming closer to standard English and losing some of its distinctive linguistic features. The following article attempts to identify whether an assimilation to standard English is currently taking place among Singlish speakers, and if so, which categories of speakers are leading the change. The study focuses on one particular feature of Singlish: missing (or “dropped”) tense words, including copular verbs and tense auxiliaries. In order to collect data on this phenomenon, a survey and subsequent transcript analysis of eight YouTube videos from four young Singaporean content creators was conducted to identify tense word dropping rates for various Singlish speakers over time.

Introduction and Background

Singapore has long been the converging point of various languages and cultures, having spent the better part of 100 years shifting from British to Japanese to Malaysian control before gaining its independence in 1965. With four official languages—English (which serves as a lingua franca and facilitates cross-ethnolinguistic interaction), Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil—it’s no surprise that Singapore eventually developed a unique variety of English that pulls features from the three other languages. Today, Singapore Colloquial English (commonly known as Singlish) has “a distinctive phonology, syntax and lexicon” (Lim, 2004) that were created at the hands of the city-state’s bustling multilingual population.

One recognizable aspect of Singlish, for instance, is the absence of tense marking in a sentence. Missing tense words are a replication of Mandarin Chinese syntax, in which elements like copular verbs are optional and often dropped (Tan, 2017). The Eton Institute demonstrates how tense is dropped in the sentence She is scared, instead giving She scared in Singlish (5 Unique Features of Singlish, 2021).

The usage of Singlish has not always, however, been without controversy on the Southeast Asian Island. In 2000, the Singaporean government launched the Speak Good English Movement (SGEM) “in a bid to delegitimize and eliminate Singlish” (Tan, 2017). The campaign, ongoing as recently as 2019, “often [featured] Singlish as an example of ‘bad English’,” (Tan, 2017) and has started a push for Singlish speakers to adopt standard English speech features. Along with the recent expansion of global platforms like YouTube that expose Singlish speakers to broader audiences of standard English speakers, this raises the question of whether Singlish may actually be in the process of becoming closer to standard English and losing some of its distinctive linguistic features.

The following research focused on missing (or “dropped”) tense words in Singlish syntax, attempting to detect whether this Singlish feature is becoming less frequent in favor of tense word inclusion, which is typical in standard English. Through investigating the speech of millennial and Gen Z (20- to 30-year-old) Singlish speakers of varying registers, the study hoped to identify whether Singlish appears to be assimilating to standard English and which groups of Singaporeans (within what sociolinguistic context and/or from what social category) are at the center of the change.

Study Design

To collect data on missing tense words—specifically, copular ‘be’ and tense auxiliaries ‘be’, ‘do’, and ‘have’—we conducted an analysis of recorded Singlish speech from the videos of four popular Singaporean YouTube channels: Jianhao Tan, bongqiuqiu, Brenda Tan, and Night Owl Cinematics. Each of the creators falls in the 20’s to 30’s age range, consistent with the hypothesis that any potential language change is happening currently and as a result of recent developments in the past two decades, such as the SGEM.

Two potential motivating factors of language change were considered in the study’s design: speaker agency and recency.

First, we divided our four YouTube channels into two categories that represent two registers of speech, which we called “Scripted” and “Unscripted.” Jianhao Tan and Night Owl Cinematics, who produce comedy content like skits and sketches, fell into the Scripted category. Meanwhile, bongqiuqiu and Brenda Tan, who produce lifestyle and vlog-type content, were chosen for the Unscripted category. By watching videos from channels with opposing content styles, we hoped to compare tense word dropping across differing language contexts.

Additionally, we wanted to capture potential language shifts over time, independent of Scripted and Unscripted categorizations. We chose two videos to analyze from each of the four YouTube channels (for a total of eight videos): one from 2021 (the year of the study) and one from five or more years ago.

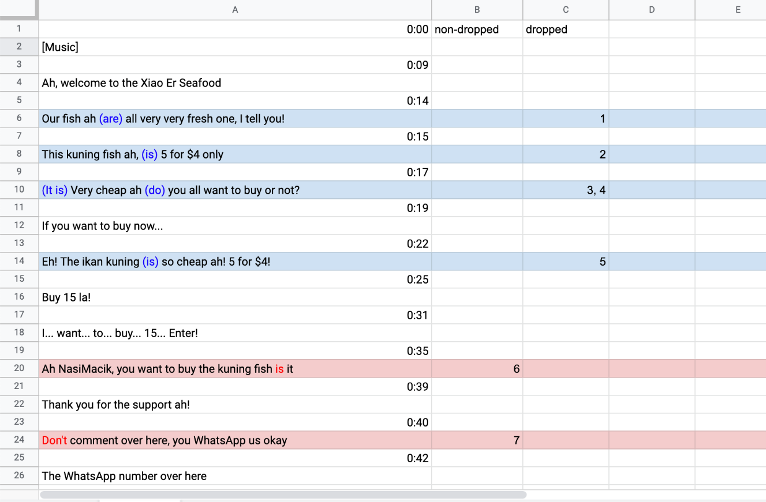

For each video, we edited and annotated auto-generated or provided speech transcripts. Relying on our intuition as native speakers of a standard variety of English, we marked each instance of tense word dropping or inclusion on the transcripts. We then reported the number of clauses with tense word droppings as a percentage of the total spoken clauses that would require tense word inclusions in standard English. More tense droppings would indicate a closer association with Singlish features, while fewer would indicate a closer association with standard English.

As we began collecting data, we expected to see that our Scripted YouTubers would show lower tense word dropping rates than our Unscripted ones. With the ability to pre-plan dialogue, we thought that they would be more conscious of their language use and exercise larger agency over their speech. We also expected that recent videos from the past year would show lower rates of tense word dropping than older examples, demonstrating an ongoing progression of Singlish adopting standard English features.

Results and Analysis

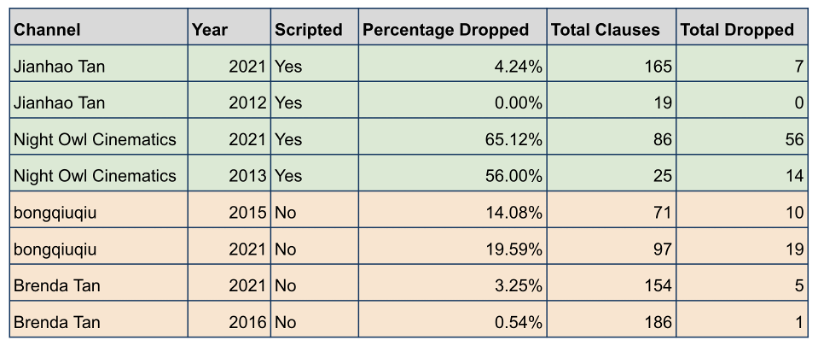

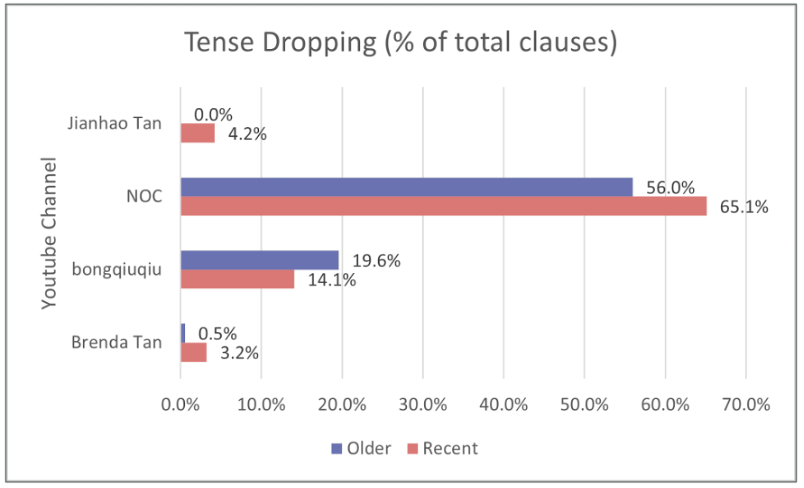

Out of four YouTube channels and eight videos, we found Night Owl Cinematics—a Scripted channel—to consistently show the highest rates of tense dropping (Figure 1), with over 50% of applicable clauses missing tense words. Brenda Tan—an Unscripted channel—showed the lowest rates, consistently having a less than 4% tense word drop rate.

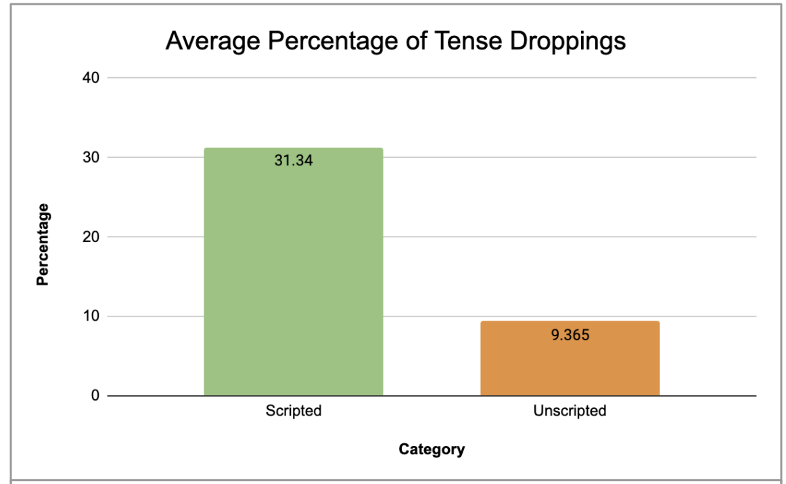

A closer look at our data revealed unexpected results. For instance, the average tense word dropping rate observed in Scripted videos ended up over three times higher than that in Unscripted videos (Figure 2). In other words, the content creators who we thought would make the most use of speaker agency to hide a Singlish feature like missing tense actually exhibited the feature much more frequently, on average.

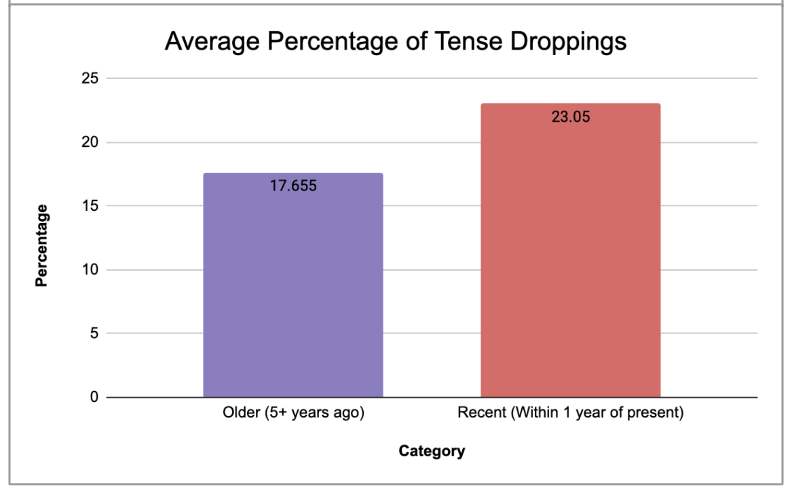

There also seemed to be a slight difference when we compared tense word dropping rates in recent and older videos. Tense word dropping occurred more frequently by roughly 5 percentage points in recent videos, contrary to our hypothesis that the Singlish feature of missing tense would be fading as time went on.

However, we noted that since our data came from a small sample size of just four YouTube channels, it wasn’t immediately obvious whether this increase was particularly significant. We decided to take another qualitative look at our data.

First, we noticed that within the categories of speech register that we chose (Scripted and Unscripted), the percentage of tense word dropping was highly varied. For instance, Night Owl Cinematics and Jianhao Tan both represented our Scripted category; while Night Owl Cinematics’ videos showed missing tense in over half of all applicable clauses, Jianhao Tan essentially did not drop tense words at all (Figure 4). This suggested to us that there was little to no pure correlation between the Scripted factor alone and tense word dropping.

Interestingly, the tense word dropping rates did not vary significantly within a YouTube channel’s own content. The frequency of missing tense did show a relative increase in the more recent videos for three out of the four channels (Figure 4), which was possibly indicative of a more general trend in Singlish. However, the small sample size of our study made it unrealistic to definitively conclude whether time was a significant influencer of tense word dropping rates and whether missing tense is actually becoming more frequent in Singlish as time goes on.

These results led us to formulate a few possible explanations for what we observed. For instance, tense word dropping rates may be more closely correlated overall with the language background you came from (perhaps where in Singapore you grew up or in which language or ethnic community) or personal linguistic style. This would explain why each individual speaker’s missing tense rates were relatively consistent all in all, while comparing two different speakers (even across the same Scripted or Unscripted category) showed larger variation. These seem to be more plausible factors than year or speaker agency, as we originally thought.

We also noted, for example, that Night Owl Cinematics specifically brands themselves as a “Singaporean humour” channel—their content specifically hopes to showcase Singaporean culture and life. This might explain why, though they have strong agency over and can pre-plan dialogue, Night Owl Cinematics showed prominent tense word dropping: they have a motivated interest in sharing the unique characteristics of Singaporean language use.

Discussion, Conclusion, and Expansion

Ultimately, there is not enough evidence in our data to claim that Singlish is becoming closer to standard English and adopting its features. In fact, many of our results appeared to suggest otherwise.

There are a few points in our research that, if modified, could lead to more conclusive descriptions of the current landscape of Singlish’s evolution. It should be kept in mind, for instance, that we surveyed a limited subject pool of four content creators and a small sample size of two videos for each creator. We also looked only at online personalities with large audiences not just from Singapore, but elsewhere around the globe. This may, consequently, have resulted in the Hawthorne effect, where speakers alter their usual speech when under the conscious observation of an audience.

Further research into this topic could be focused on looking at potential influences of Singlish on Singaporeans who are attempting to learn or speak a more standard variety of English, such as Singaporean international students or Singaporean nationals living and working in the United States. Additionally, investigating the speech of local Singaporeans rather than just that of online and public figures would provide a more holistic picture of how Singlish is adopting (or not adopting) standard English features. Surveying a larger sample size of videos that span a more extended time scale would give better insight on Singlish languages changes over time. Studying other features, beyond missing tense or even beyond syntax, could also provide a more well-rounded idea of how Singlish is shifting over time.

Finally, although our findings did not line up with our hypothesis, we were able to make other interesting observations based on the data collected.

It appears, first of all, that our speakers showed a clear awareness of the difference between standard and Singlish English features at times. For instance, take the following Night Owl Cinematics video from 2021, “Types of Online Shoppers”. While the written subtitle reads, “How many do you want?” (Image 3), the speaker actually pronounces the following utterance: “How many you want?” This seems to show a conscious acknowledgement of what is typical in standard English syntax, in striking juxtaposition to what was natural to the Singlish speaker.

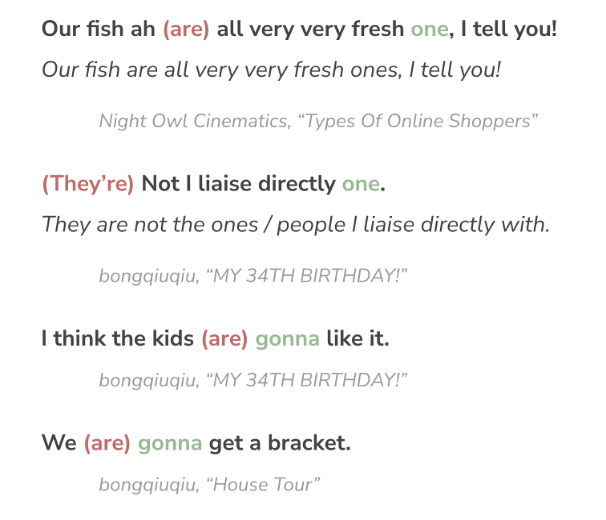

Moreover, we were able to confirm from our data that tense word dropping appears to be not random but systematic and motivated (part of Singlish grammar; not randomly distributed) in Singlish, as Lim (2004) had suggested was the case with phonological, syntactical, and lexical features of the variety. We can review a few examples (Image 4), which show two systematic instances of tense word dropping. We firstly see that the feature of missing tense seems to appear in conjunction with the Singlish particle ‘one’; in both a Night Owl Cinematics and a bongqiuqiu video, the speakers use the particle at the end of the clause and drop that same clause’s earlier copular verb. In a similar phenomenon, the missing of the tense auxiliary ‘are’ appears in conjunction multiple times with the auxiliary ‘gonna’, where the utterance of the latter seems to trigger the dropping of the tense auxiliary immediately before it.

So, is Singlish becoming more and more like standard English? It’s hard to say. What seems to hold is that Singlish has unique and systematic features, of which the distribution varies among its diverse speakers. The tangible influence that campaigns like the Speak Good English Movement have on non-standard varieties and their assimilation to standard forms of a language remains to be seen.

References

5 Unique Features of Singlish. Eton Institute. (2021, May 24). Retrieved October 15, 2021, from https://www.etoninstitute.com/wp/2021/05/24/5-unique-features-singlish/.

Gopinathan, S. (1979). Singapore’s Language Policies: Strategies for a Plural Society. Southeast Asian Affairs, 280-295.

Leimgruber, J. R. E. (2013). Singapore english: Structure, variation and usage. Cambridge University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908382.

Lim, L. (Ed.). (2004). Singapore English: A grammatical description (Vol. G33). John Benjamins.

Tan, Y. (2017). Singlish: An Illegitimate Conception in Singapore’s Language Policies? European Journal of Language Policy 9(1), 85-104. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/657324.