Kevin Kim, Shoichiro Kamata, Karin Yamaoka, Raine Torres, Max Fawzi

Japanese is often erroneously considered a “swearless language”, but anyone who has ever been yelled ‘しね’ (meaning ‘to die’) will confidently tell you that like all languages, Japanese has diverse ways of encoding abusive language. In Japanese ‘しね’ only becomes abusive language when in the context of being an insult, but in everyday situations the word simply means ‘to die’ without any connotation of insult. English differs from Japanese by having explicit profanities that carry a vulgar meaning independent of its usage context or syntactic environment. We conducted the following research to discover the discrepancy of semantic typology between Japanese and English profanities or abusive language, and if bilingual speakers endow varying emotional intensity to English profane lexica compared to Japanese abusive language. Our study shows that L1 Japanese L2 English bilinguals view English profanities as less offensive than their L1 English counterparts, report using these English profanities more frequently, and view the equivalent Japanese abusive language as more offensive.

Introduction and Background

Languages differ significantly in how they encode and express emotions, particularly when it comes to the use of profanity as a means to express anger (for example in the context of an argument). This study examines profanities as a distinct subset of lexicon characterized by inherently vulgar or aggressive meanings, distinguishing them from other words or expressions that acquire such connotations only through context. In other words, in this paper, profanities refer to lexically explicit terms such as ‘fuck’ in English, that convey hostility or vulgarity without the necessity for context, and argue that Japanese lacks such a distinct subset, since words like ‘しね’ (meaning ‘to die’) can convey aggression or intensity, but lack the explicit vulgarity found in English profanities. This study thus examines and defines profanities as vulgar lexica (found often in English) where its vulgarity is unaffected by its syntactic environment or context; distinguishing them from abusive expressions that only acquire offensive undertones within specific contexts (found often in Japanese). More specifically, Japanese speakers use “various markers of register rather than the explicit deployment of dysphemistic lexical items or expressions” (Jackson & Kennet 2021,1), where connotation of abuse is only endowed through syntactic and environmental inferences (context in which it is being used) even though there can be contextually impolite vocabulary derived from anatomical, excretory, and sexual sources like in English (Hoshino 1971, 31). We will refer to the vulgar and aggressive lexica of English as ‘profanities’ whereas ‘abusive language’ will be used for their Japanese counterpart lexica.

We argue that current studies on Japanese do not accurately reflect empirical use of abusive languages by native speakers. Medias (e.g. anime) that use more performative language tends to distort the perception of how Japanese speakers use language as media lexicons are often unreflective of native speakers’ lexicons. Through this study, we aim to focus on what native speakers consider to be consistently employed in their everyday language.

With our definition of profanities, it assumes a discrepancy of linguistic equivalence between English profanities and Japanese abusive language in its aggressiveness in its use. Therefore, it raises a question; How do Japanese L1 and English L2 speakers juggle the two discrepant lexical categories of ‘profanities’ and ‘abusive language’ and navigate through the lack of equivalence as a bilingual?

We aim to gain an understanding of the cognitive processes that occur for bilingual speakers, when conceptualizing constructs that are not lexically represented in their L1 and discrepancies in linguistic equivalence.

A research by Dewaele (2016) offers a valuable insight into self-reported perception of English swear words by L2 English speakers. The findings show that English LX users (non-native English speakers) over-estimate the offensiveness of most negative emotion-laden words, and avoid using most offensive emotion-laden words. On the other hand, a relevant study by Gawinkowska et al. (2013) found that bilingual speakers are more hesitant to use strong expletives in their L1 than in their L2, likely because they feel less bound by normative influences when speaking in their L2. As such, existing research has presented conflicting results, adding layers of complexity to bilingualism and emotional perception of abusive language in L2 languages.

We expect cultural aspects to play a role in the perception as well; Japanese cultural norms generally discourage direct expressions of intense emotion. One way this manifests is through face, as in outward appearances. Lin & Yamaguchi (2011) state that Japanese culture places greater importance on saving face, as face in collectivist cultures is concerned with an individual’s position in the social hierarchy rather than personal achievement like in individualistic cultures; there is also a tendency to avoid conflict and maintain interpersonal harmony in collectivist cultures. By directly expressing strong emotions, one would lose face in Japanese society and thus there is a social pressure against directly expressing intense emotion. Synthesizing the relevant studies and Japanese cultural aspect, we hypothesize that L1 Japanese speakers will perceive English profanities as being less emotionally charged than their L1 English counterparts. We can also expect L1 Japanese speakers to rate Japanese abusive language roughly the same as their English profanity counterparts or as less offensive overall.

Methods

2.1 Participants

The population of our study is L1 Japanese L2 English speakers, with our control group being L1 English speakers having no knowledge of Japanese. L1 Japanese L2 English bilingual participants are Japanese nationals who did not grow up speaking English at home; their English proficiency were established in the demographic section of the survey including questions regarding their language background. Furthermore, all participants are current college students for ease of recruitment and consistency, putting the age range between 18-28 years old, an age group which likely has the same general vocabulary and therefore slang/profanities, allowing for more homogenous data.

2.3 Design

The survey method was chosen to measure perceptions of both Japanese abusive language and English profanity. It consisted of two phases, where phase 1 focuses on the translation and interpretation of English profanities, and phase 2 focuses on the emotional charge and frequency of use of profanities.

2.3.1 Phase 1

Japanese media often, for performative effect, distorts how abusive language is used; this however does not reflect how native speakers use abusive language. We thus established a list of 10 Japanese abusive expressions with our own English translations, and asked a group of L1 Japanese L2 English speakers (N1 = 14, 7 male, 7 female) to translate the predetermined English words into Japanese. The results became a basis for the subsequent phase and also a tool to identify abusive lexica that native speakers (18~28) actually use.

2.3.2 Phase 2

A separate survey was sent to both our control group (N2 = 16, 8 male, 8 female) and to our experimental group (N3= 13, 3 male, 10 female). The survey asked participants to rate on a 5-point scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high) with regards to a given abusive expression/profanity (1) how well they understand the meaning, (2) how offensive/emotionally charged it is, and (3) how frequently they use it. The control group of L1 English speakers rated solely English profanities, while our experimental group rated both English profanities and Japanese abusive language.

2.4 Manipulation

To standardize the implied usage context of the profanities (as emotional intensity could be influenced by the varying situations that participants imagine its usage to be), every survey were presented with a GIF of two men arguing, to standardize the perception that the profanities/abusive language in question are used by a person demonstrating anger. Moreover, phase 2 had two versions of the same survey, where Version 1 asked participants to rate English profanities first and of Japanese abusive language second, and vice versa. This was done in hopes of mitigating anchoring effects or priming effects that could bias our findings.

Figure 1: GIF presented to participants during phase 2 survey

Results and Analysis

3.1 Phase 1 Results

This phase primarily served to establish the abusive language in Japanese that reflected the actual terms used by native speakers. A key finding was in regards to the perception of “shit” and “fuck”: L1 Japanese speakers tend to view “shit” and “fuck” as synonymous when translated into Japanese. Approximately 86% of respondents translated both “shit” and “fuck” as 「クソ」(kuso). This pattern likely reflects the absence of a direct Japanese equivalent for the word “fuck.” Instead, respondents opted for 「クソ」(kuso), which semantically corresponds more closely to “shit” as it denotes fecal matter. This semantic overlap highlights a gap in linguistic equivalence, influencing the way these terms are interpreted and used in the context of L1 Japanese speakers.

Another key finding was that the translations for “dumbass” and “moron” were predominantly split between two responses: 「バカ」(baka) and 「あほ」(aho). Slightly more respondents translated “dumbass” as 「バカ」(baka), while “moron” was slightly more frequently translated as 「あほ」(aho). For the subsequent phase of the study, we selected the more commonly chosen translation for each term, though the differences were minimal. This suggests that, for Japanese speakers, profanities targeting intellectual levels exhibit limited variability in their translations, possibly reflecting a convergence in semantic interpretation.

The patterns presented were indicative of the nuanced ways in which abusive language is conceptualized and translated by L1 Japanese speakers. Specifically, the findings highlight the challenges of mapping English profanities to Japanese equivalents due to cultural and linguistic differences.

3.2 Phase 2 Results

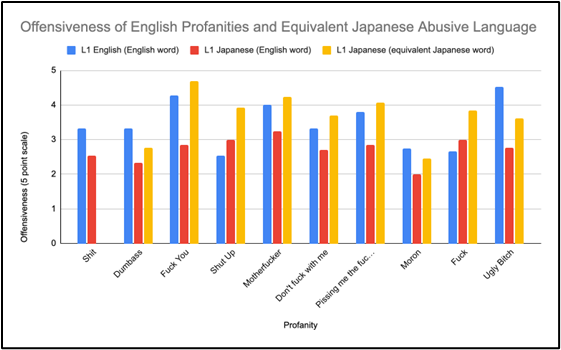

Quantitative analysis of phase 2 reveals that on average L1 Japanese bilinguals view English profanities as 0.73 less offensive on the 5 point scale than L1 English speakers, with our experimental group rating the 10 English profanities as an average of 2.73, and the control group rating them as 3.45. The largest differences were found in “Ugly Bitch” (difference of 1.76) and the more commonly used “Fuck you” (difference of 1.42), which reflects a significantly different attitude towards even more common swearwords. Our experimental group also viewed the two most commonly used profanities “Shut Up” and “Fuck” as more offensive, with small differentials of 0.47 and 0.33 respectively. Our experimental group however, also rated the selected 9 Japanese translations at an average of 3.70 on the offensiveness scale (i.e. 0.25 higher than the English profanities), with the most offensive being 死ね, equivalent of “Fuck you” with a rating of 4.69 on the offensiveness scale.

Figure 2: Summary of the offensiveness of English profanities and equivalent Japanese abusive language

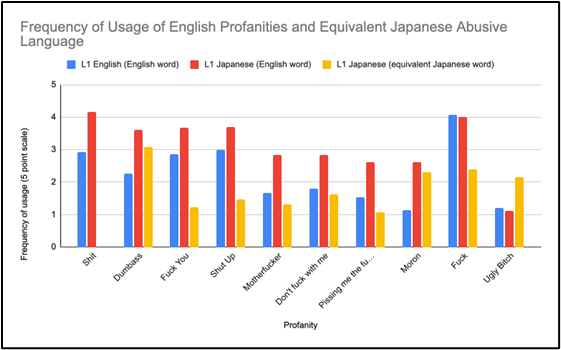

When it comes to frequency of usage, L1 Japanese bilinguals also reported using the English profanities at a higher frequency, with self-reported frequency being 0.87 points higher than their L1 English counterparts. This was the case for almost all English profanities across the board with the exceptions of “Fuck” and “Ugly Bitch” which had near equal usage; the largest differentials were found in “Moron” (difference of 1.48) and “Dumbass” (difference of 1.35). Interestingly, L1 Japanese speakers reported a rather low frequency of usage for the counterpart Japanese abusive language, with an average of 1.85 on the 5 point frequency scale. The most frequently used one being 「バカ」equivalent to “Dumbass” at 3.08, followed farther behind by 「クソ」 equivalent to “Fuck” at 2.38. This reflects the less frequent use of abusive language in Japanese compared to English which uses profanities more freely. This also corroborates the higher offensiveness of Japanese abusive language, which is used more infrequently and thus packs more of a punch.

Figure 3: Summary of the self-reported frequency of usage of English profanities and equivalent Japanese abusive language

Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Phase 1 Discussion

In Phase 1, we found that L1 Japanese speakers used the same word 「くそ”」 (kuso) as an approximation for both “shit” and “fuck”. While this was not something that we had initially hypothesized, our findings in Phase 1 supported the idea that the Japanese language has less explicit profanities as previously found in research such as Jackson & Kennet (2021), highlighting the semantic overlap in the translation of “shit” and “fuck”, which underscores the limited availability of distinct Japanese terms that capture the unique connotations of these words in English. Similarly, the minimal variability in the translation of “dumbass” and “moron” suggests that Japanese speakers may perceive insults related to intellectual capability as largely interchangeable, pointing to a possible variability from L1 English speakers in how such terms are employed and understood.

4.2 Phase 2 Discussion

In Phase 2, we found that L1 Japanese speakers viewed English profanities as less offensive than L1 English speakers in all but two instances (“Shut Up” and “Fuck”). This aligned with our hypothesis that L1 Japanese speakers would perceive English profanities as being less emotionally charged. However, this contrasted with the findings of the Dewaele (2016) study which found that non-native English speakers would overestimate the offensiveness of English profanities and avoid using them. Our findings, instead, seemed to align more with Gawinkowska et. al (2013) which found that bilingual speakers were actually more inclined to use strong expletives in their L2 because they felt less bound by the norms of their L1. In our study, we saw evidence of this from the higher rates of usage for English profanities by L2 Japanese speakers than L1 English speakers. Japanese L1 speakers also rated the Japanese approximations of English swear words as being higher in offensiveness than the English swear words themselves. In the midst of conflicting research, we found that our findings followed similar patterns to Gawinkowska et. al. This may be due to the deeply ingrained collectivist cultural norms and emphasis on face-saving that exists in Japanese culture (Lin & Yamaguchi 2011) that may make L1 Japanese speakers more sensitive to abusive language in their native tongue.

4.3 Overall Discussion

This study offers some insight into the perceptions of emotional words in an L2. In our case, this refers to the use of profanities that are explicit without context for speakers who are familiar with abusive language that require context to be abusive. Research that helps understand these experiences will hopefully contribute to a wider understanding of interpersonal connection by identifying the ways language can cause miscommunications due to differences in culture as well as the language itself. Interestingly, additional observations suggest that non-English speakers often react with surprise or discomfort when exposed to the meaning of English profanities. In a street interview conducted by Asian Boss (LINK), Japanese people shared that they find such language uncomfortable and showed that abusive words are rarely used in Japanese culture. This observation also occurs among English speakers with Japanese people. According to the discussion in the Podcast “Hapa 英会話 Podcast – 第305回「汚い言葉遣い」”(LINK) , some English speakers try not to use the profanity with Japanese people even when they are talking each other in English. This similarity shows that hesitation from using profanity comes from the differences across cultural backgrounds regarding when it is appropriate to use profane language, which gives insight to the experiences of Second Language Learners as they navigate unfamiliar territories. These reactions further emphasize the cultural and linguistic differences in how profanities are perceived and used between English and Japanese speakers.

While our research was limited to only include college-aged students, future research would ideally expand the scope to include a variety of ages and educational backgrounds. Future research could also compare our findings with Japanese L1 speakers to another L1 language with contrasting conventions of abusive language.

References

Dewaele, J.-M. (2016). Thirty shades of offensiveness: L1 and LX English users’ understanding, perception and self-reported use of negative emotion-laden words. Journal of Pragmatics, 94, 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.01.009

Gawinkowska, M., Paradowski, M. B., & Bilewicz, M. (2013). Second language as an exemptor from sociocultural norms: Emotion related language choice revisited. PLOS ONE, 8(12), e81225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081225

Hoshino, Akira (1971). Akutai mokutai kō – akutai no shosō to kinō. [Thoughts on Abusive Language. Aspects of Abusive Language and its Functions]. Kikan jinruigaku 2(3): 29– 52.

Jackson, L., & Kennett, B. (2021). Slang and taboo language: An analysis of swearing guides for L2 Japanese learners. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 21(2). Retrieved from https://japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol21/iss2/jackson_kennett.html

Lin, C.-C., & Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Effects of face experience on emotions and self-esteem in Japanese culture. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(4), 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.817

Relevant Info: Hapa 英会話 Podcast. (2020). 第305回「汚い言葉遣い」[Podcast]. Retrieved from https://podcasts.apple.com/jp/podcast/hapa%E8%8B%B1%E4%BC%9A%E8%A9%B1-podcast/id814040014?i=1000491739815 Asian Boss. (2018). Japanese React to English Swear Words [YouTube video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KHpw5p8qCrI&t=61s