Hee Suh, Misuzu Nakazawa, Jafarri Nocentelli, Rutvi Shah, Joaquin Cruz

Introduction and Background

K-pop stands as a global phenomenon, not only for its captivating performances but also for its seamless integration of English and Korean. This study investigates how code-switching, which refers to alternating between two or more languages within a single sentence, enhances audience engagement in K-pop. By comparing older (pre-2015) and newer (post-2015) K-pop tracks, we analyze how the use of English has evolved alongside K-pop’s increasing global popularity. We focus on two listener demographics, L1 Korean monolingual listeners and global audiences, including L1 English monolinguals. The language aspects we are working with include intra-sentential code-switching and phonological adaptation. Our research aims to paint a comprehensive picture of code-switching’s role in shaping K-pop’s appeal. L1 Korean participants will be more likely to notice the adaptation, while L1 English speakers will likely notice increased English usage over time.

In this article, we investigate how code-switching in K-pop functions, focusing on its role in enhancing audience engagement. Intra-sentential is a type of code-switching where elements from one language (English) are embedded within a sentence structured primarily in another language (Korean). For example, a K-pop song might use an English verb or noun phrase, such as “make it rain” or “crazy 사랑” (crazy love), within a Korean sentence. This use of English within Korean sentences can enhance the song’s appeal to both Korean listeners and a global audience. Our target population includes individuals between the ages of 18 and 21, both L1 Korean monolingual speakers as well as global listeners, L1 English monolinguals, with minimal K-pop exposure. Our research will analyze phonological adaptation focusing on rhythmic and prosodic adaptations of English within Korean phrasing. This type of adaptation involves adjusting English words to fit the rhythmic and prosodic structure of Korean music. K-pop blends English into Korean lyrics by adapting to differences in rhythm where Korean’s syllable timing versus English’s stressed pattern makes the music appeal to both global and Korean listeners. The theoretical framework we will use is the Myers-Scotton’s Matrix Language Frame (MLF) to analyze how English integrates into the Korean structure and appeals to monolingual Korean listeners. The selected artists are global K-pop stars popular in LA, an ideal setting to study phonological adaptability due to the growing local fanbase of the genre (Burt, 2024). Our research question is: How has English usage in K-pop evolved across different popularity levels, and how does this linguistic adaptation resonate with different subsets of audiences (L1 Korean monolinguals versus global appeal)? Our hypothesis suggests that the use of English in K-pop has grown between 2015 and 2024. As its popularity grew internationally, code-switching has increased between Korean and English. In songs aimed at global audiences or informal settings, we expect more frequent code-switching and phonological adaptations. In contrast, songs focusing on cultural authenticity or Korean listeners may use English more selectively. Due to strategic linguistic adaptations, the patterns of syllable and stress have evolved in response to the increasing globalization of K-pop. Before this study, the specific patterns of phonological adaptation of English within K-pop and their differential impact on L1 Korean versus L1 English listeners were not fully understood.

Methods

Before looking straight into the phonological particles of this study, we want to understand the difference between the English language of older and newer K-pop songs. To do so, two participating groups completed a demographic Google survey sent through emails: Three L1 English monolinguals with minimal K-pop exposure and three L1 Korean monolinguals. These two groups were explicitly chosen because L1 Korean monolinguals understand and speak the domestic language of the songs(Korean), and L1 English monolinguals with minimal exposure have limited background knowledge of the Korean language, representing the global language and audience.First participants were asked general demographics, then presented with some terms and concepts to help participants understand the study better, such as rhythm and stress and what older era, songs released before 2015 and newer eras were songs released after 2015. After understanding the terminology, they were told to listen to the first two verses of two songs: one older and one newer release track from one of the K-pop artists, BTS and Seventeen, who are popular in LA. A little background was that the debut of PSY’s song “Gangnam Style” paved the way for international concerts to rise, with the global market growing by 44.8% in 2020.(Glasby, 2021; Oos, 2023). The years 2015 and 2022 were chosen with this fact in mind, where in 2015, many of the current popular K-pop artists debuted. One of them is Seventeen, and the other is BTS. The songs from Seventeen were: “Mansae” (2015) and “HOT” (2022), and the songs from BTS were “DOPE” (2015) and “Yet to Come” (2022). At the end of the survey, we asked two essential questions: 1) Do the English lyrics in this song match the Korean rhythm and pronunciation, and 2)Can you identify specific words or phrases where the English lyrics were adapted? By identifying the two questions, we analyzed the differences in which they noticed and what type of changes each group noticed more.

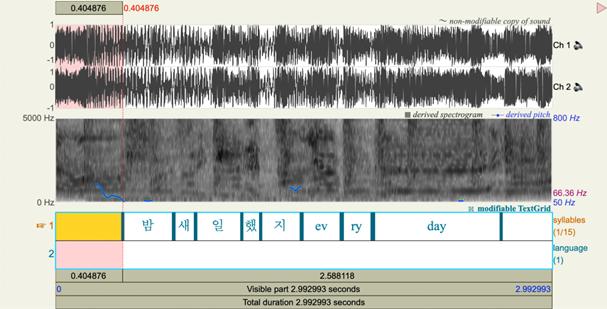

In order to conduct our qualitative data, we investigated stress patterns in the English lyrics of K-pop songs using Praat software. Stress was measured by analyzing spectrograms and waveform data, identifying syllables with higher intensity peaks, and recording their durations in milliseconds. These measurements helped us determine how stress in English lyrics was adapted to fit the balanced rhythmic structure of Korean songs. In this analysis, we also examined the alignment of stressed syllables with surrounding Korean lyrics to understand the degree of rhythmic congruence.

The methodology was designed to capture the differences in stress and rhythm between Old and New Era songs, using precise timestamps to compare English syllables embedded in bilingual lyrics. For example, in “Dope” (BTS), an Old Era track, the word “party” maintained its natural English stress pattern, with the second syllable emphasized and lasting approximately 200 milliseconds longer than the average Korean syllable. By contrast, in “Yet to Come” (BTS), a New Era song, the phrase “dreams come true” exhibited more balanced syllable durations, where each syllable was approximately 140 milliseconds, blending seamlessly into the Korean rhythm. These observations were validated through auditory analysis to ensure that the measurements aligned with listeners’ perception of rhythmic congruence.

Exploring stress and rhythmic patterns in this way is critical for understanding bilingual media consumption. In bilingual contexts like K-pop, successful integration of English lyrics into Korean songs depends on aligning distinct rhythmic and phonological systems. By adapting stress patterns to conform to Korean syllable timing, producers create a more cohesive listening experience for both local and global audiences. This analysis thus sheds light on how bilingual media can balance cultural authenticity with accessibility, enhancing its appeal across linguistic boundaries. To collect quantitative data, once again using Praat, we looked into one line from each song that contained intra-sentential code-switching to analyze the syllable duration for each language. Separating each syllable into its own section, we first measured the syllables in milliseconds and added each syllable to its belonging words. This is due to the need to account for the rhythmic adaptation of English stress patterns within Korean phrases, keeping both languages’ syllable duration more precise to compare. Then, we calculated the average syllable duration for each language and compared the length in older and newer songs to see if, in newer songs, the English words were phonologically adapted to align with their Korean counterparts.

Results and Analysis

Figure 1: BTS “DOPE” syllable duration Results and Analysis

Our study revealed increased integration of English lyrics and phonological adaptations over time. This was first highlighted in our findings from our Google survey, the data of which was converted into a graph generated by Python.

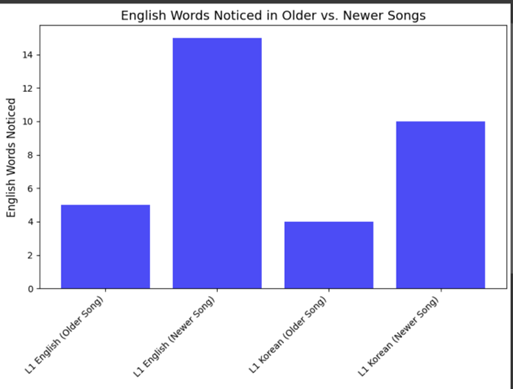

The graph below represents two pieces of data collected from the Google form. The left graph shows the results from “English Words Noticed in Older vs. Newer Songs,” and the right graph shows the “Adaptation Noticed in Older vs. Newer Songs.”

Figure 2: Google Survey Python Generated Charts

The first graph revealed that L1 English monolinguals with minimal K-pop exposure noticed significantly more English words in newer songs than in older songs. In older songs, they noticed a mean of 5 words and a mean of 15 in newer songs. Similarly, L1 Korean monolinguals also saw an increase in English lyrics, though they noticed slightly less than L1 English monolinguals. In older songs, they noticed a mean of 4 and 10 words in the newer songs. In contrast, the second graph revealed that L1 korean monolinguals were more likely to notice phonological adaptations in newer songs, reflecting shifts toward a more balanced syllable usage that aligns English with Korean rhythm and timing. As presented in the graphs, L1 English speakers were slightly less likely to realize these phonological adaptations. These findings underline how newer K-pop tracks cater to both global and domestic audiences through strategic adaptations where English lyrics are adjusted to preserve their clarity while fitting into the korean rhythm.

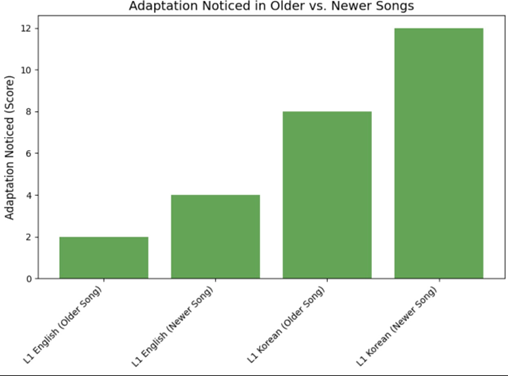

Our study highlights a significant evolution in the integration of English lyrics and their phonological adaptations in K-pop over time. Using Praat software, we observed how syllable durations evolved, showcasing the interplay between English stress patterns and Korean rhythmic norms across Old and New Era songs.

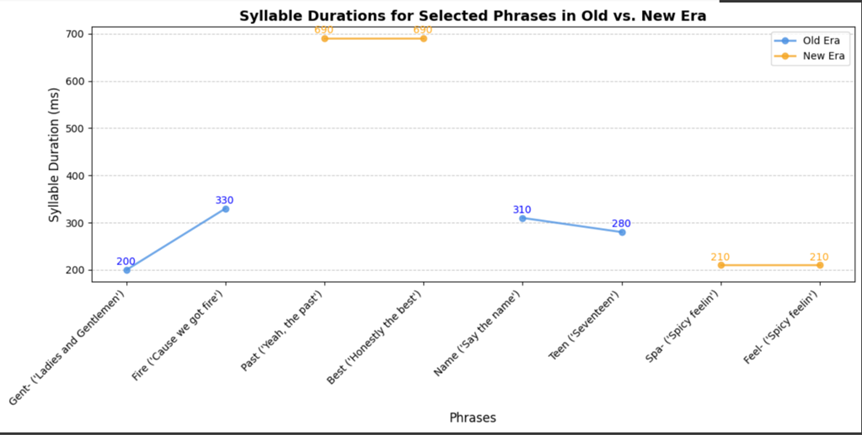

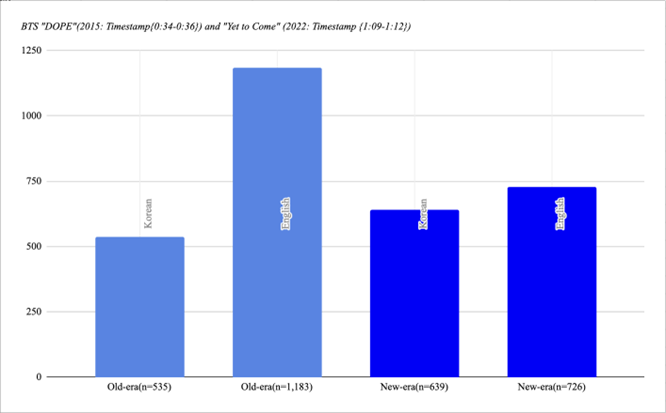

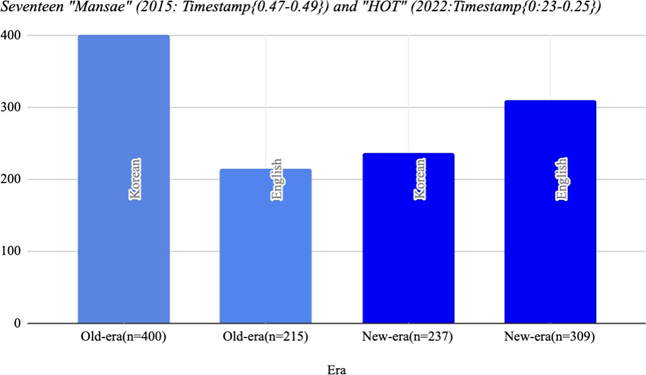

In “Dope” (BTS), an Old Era track, English stress often disrupted Korean rhythm. For instance, the syllable “Gent-” in “Ladies and Gentlemen” lasted 200 ms, longer than the Korean syllable “Ayo” at 180 ms. Similarly, “Cause we got fire” featured “fire” at 330 ms, highlighting mismatched timing. Conversely, the New Era track “Yet to Come” (BTS) exhibited greater alignment, with “past” and “best” balanced at 690 ms, closely matching adjacent Korean syllables. A similar trend was seen in Seventeen’s “Mansae”, where mismatches occurred with “name” at 310 ms and “teen” at 280 ms. However, in “Hot”, the New Era song, phrases like “Spicy feelin’” featured evenly timed syllables (~210 ms), harmonizing with the Korean rhythm. Aggregated averages reinforced these findings: in “Dope”, Korean syllables averaged 535 ms, while English averaged 1,183 ms, creating a 500 ms gap. This narrowed significantly in “Yet to

Come” to a 100 ms gap (639 ms vs. 726 ms). Similar alignment improvements were observed in Seventeen’s tracks. These results highlight the significance of adapting English stress patterns to fit Korean rhythms in bilingual media consumption. Such adaptations enhance accessibility for both global and local audiences, enabling K-pop to transcend language barriers. By harmonizing distinct phonological systems, producers create music that resonates culturally and emotionally with diverse audiences. This strategic linguistic integration underscores K-pop’s role as a global phenomenon, balancing cultural authenticity with international appeal.

Figure 3: Syllable Duration of Old Vs. New Era Songs Generated via Python

Figure 4: Syllable Duration for Phrases of Interest (Old vs. New Era) Generated via Python

Figure 5: Python Code For Figures 3 & 4

With the praat software, we calculated the syllable duration, looked into the average syllable duration, and input it into a bar graph using Google Sheets. In the first Figure, we analyzed the syllable duration in the signs between Old and new-era songs from BTS

Figure 6: BTS “DOPE” and “Yet to Come” Syllable Duration Comparison

In the 2015 song “DOPE”, we saw a significant gap between the average syllable duration in the korean lyrics, n=535ms, and the English lyrics, n=1,183ms, resulting in a 500ms gap. But when we looked at BTS’s new-era song “Yet to Come” in 2022, the gap between the average syllable duration for Korean, n=639ms, and English, n=726ms, the duration was closer with about a 100ms gab, aligning each syllable duration closer. The same case was shown in the artist Seventeens old-era song “Mansae” 2015 and the new-era song “HOT” 2022.

Figure 7: Seventeen “Mansae” and “HOT” Syllable Duration Comparison

In “Mansae,” the average Korean Syllable duration was n=400, and the English syllable duration was n=215, resulting in a 200 ms difference. Comparing this to the newer song “HOT,” the Average Korean Syllable duration was n=237ms, and the English syllable duration was n=309ms, a 100 ms difference. Though Seventeen’s results showed less significant change than those of BTS, both cases displayed a decrease in the duration of Korean and English lyrics in their old-era and new-era songs. BTS’s songs reflected a decline in English syllable durations compared to their newer songs; in contrast, Seventeen songs demonstrate an increase in English syllable durations. Both show how the English syllables were adjusted to align with the korean syllable durations

Discussion and Conclusion

K-pop strategically uses code-switching and phonological adaptations to engage diverse audiences while maintaining its cultural identity. Despite increased English usage due to globalization, K-pop adapts English lyrics to fit Korean phonological patterns, resonating with domestic and global fans. This reflects a careful balance between cultural preservation and international reach. L1 Korean and L1 English listeners showed increased recognition of English lyrics in newer K-pop songs. However, for different reasons, L1 English listeners noted the greater prominence of English, while L1 Korean listeners recognized the phonological adaptations to Korean rhythms. This suggests intentional design to appeal to both groups, reflecting either listener adaptation or producer strategies to bridge linguistic divides.

While globalization has amplified English use, K-pop prioritizes cultural identity. Newer songs like BTS’s “Yet to Come” and Seventeen’s “HOT” demonstrate smoother integration of English lyrics into Korean rhythms compared to older tracks like “Dope” and “Mansae,” ensuring a cohesive listening experience for Korean audiences while making English more accessible to international fans. K-pop thus acts as a bridge between local traditions and global influences, transcending language barriers without losing its roots. Higher English lyric recognition in newer songs underscores deliberate linguistic strategies by K-pop producers, highlighting the genre’s ability to adapt to globalization while preserving its cultural identity. Further research is needed to determine the consistency of these trends across different K-pop groups and genres, and expanding participant diversity could provide deeper insights into how linguistic adaptations influence listener engagement and cater to domestic and international audiences.

This study illustrates how K-pop reflects broader globalization in the media. By embracing English through linguistic adaptation, K-pop reinforces cultural identity while connecting with global audiences. Balancing cultural authenticity with international appeal, K-pop offers a model for navigating bilingualism and globalization. It contributes to discussions about language’s role in cultural preservation and global expansion and demonstrates how media can connect audiences worldwide while maintaining unique cultural heritage.

References

Burt, K. (2024). How LA became the epicenter of K-Pop fandom in the U.S. Thrillist. https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/los-angeles/k-pop-in-la

Can Code-Switched texts activate a knowledge switch in LLMs? A case study on English-Korean Code-Switching. (n.d.). https://arxiv.org/html/2410.18436v1

Canagarajah, S. (2007). Lingua Franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. Modern Language Journal, 91(s1), 923–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x

Glasby, T. (2021, May 19). How K-Pop took over America: A timeline. Nylon. https://www.nylon.com/entertainment/timeline-of-k-pop-rise-in-america

Le, S., Campbell L. J., Orozco J., & SS, N. (2024). Code-Switching Habits of BTS. https://languagedlife.humspace.ucla.edu/bilingualism/code-switching-habits-of-bts/

Lee, J. (2020). Cross-linguistic prosody in K-pop music: Integrating English and Korean lyrics. Journal of Music and Linguistics, 12(3), 40–55. Luminate Data (2023). Mapping out K-pop’s global dominance. Retrieved from Luminate Data’s blog on global streaming trends.

Nazri, S. N. A., & Kassim, A. (2023). Issues and Functions of Code-switching in Studies on Popular Culture: A Systematic Literature review. International Journal of Language Education and Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.15282/ijleal.v13i2.9585

Oos, O. (2023b, December 5). When did K-Pop start becoming a global phenomenon – ononestudios.com. ononestudios.com. =The%20genre%20began%20to%20gain,to%20television%20dramas%20and%20cuisine

Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006909339814

Schneider, I. (2023). English’s expanding linguistic foothold in K-pop lyrics: A mixed methods approach. English Today, 40(2), 105-112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078423000275

Shim, D. (2005). Hybridity and the rise of Korean popular culture in Asia. Media Culture & Society, 28(1), 25–44. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254737351_Hybridity_and_the_Rise_of_Korea n_Popular_Culture_in_Asia

Zhang, J. (2023). Language, cultural hybridity, and resistance in K-Pop: A linguistic analysis of Korean pop music lyrics and performances. International Journal of Emerging Multidisciplinary Business Information Systems, 3(3), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.59889/ijembis.v3i3.186