Charlie Kratus, Julian Stassi, Evan Ludwig, Peter Tevonyan, Connor Dullinger

Starting college can be an exciting, but also an overwhelming time, especially when it comes to making friends. However, for many students, sharing their identity starts long before classes begin.

Ahead of setting foot on campus as Bruins, UCLA’s Class of 2029 is already creating their college identity online through Instagram. Newly admitted students post photos as well as a self-created caption. These short bios may seem insignificant, but they actually reveal a lot about themselves. They’re filled with a plethora of different slang, lowercase letters, and emojis.

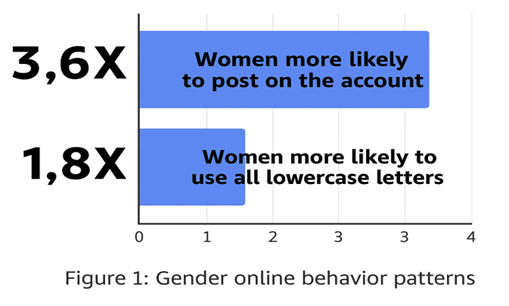

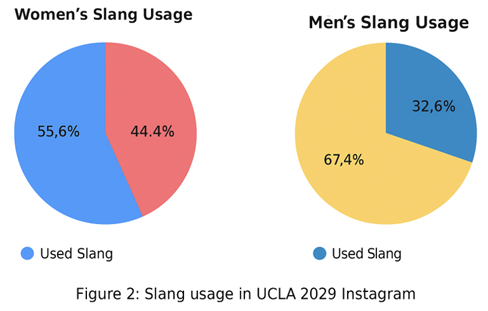

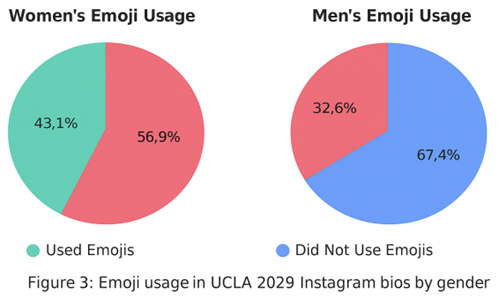

We wanted to look into how students use different types of language and slang to present themselves. We also observed whether patterns are connected to gender, major, location, or interest in Greek life. We saw clear gender-based patterns where women generally used more informal language. They were much more likely to include emojis, write in lowercase, and use slang than men. Those who identified as male tended to stick to more traditional grammar and formatting. We found that language isn’t just how students talk, it’s how they show who they are and where they fit in among different communities.

Introduction and Background

i) “Hey, my name’s Julian Stassi and I’m 1000% committed to UCLA! I’m from Sacramento, and majoring in Business-Economics. I love watching football, hanging with friends, and I’m a huge foodie. I’m looking for a roommate and planning to rush in the fall, so bang my line!”

These exact messages flood the UCLA Class Instagram page every single year. This is a space where thousands of recently admitted students introduce themselves to find roommates and friends, and it is a great way for students to start shaping their college identity before ever arriving on campus. These posts are more than just sharing majors or hometowns; they’re filled with unique sets of carefully chosen language that says something about how students want to be seen.

ii) These personal bios are filled with informal language, which makes them feel personal and distinctive. While others can be more straightforward and formal. This made us question: Does gender influence tone or slang? How are North Campus majors different from STEM majors? What connections could be made between these new Bruins, and what does this say about them?

iii) We then analyzed the first 200 posts from the official UCLA 2029 account and closely looked at the diverse use of slang, grammar, and emoji use, and how language varies across gender, major, and location. Our project explores how even small stylistic and language choices reflect deeper identity performances and social positioning within online spaces. These posts are not just about introductions; they are shaping how students want to be perceived as they begin forming who they are on campus.

Methods

For this project, like previously mentioned, we conducted our quantitative analysis by going through the first 200 posts from the @ucla2029freshman class Instagram account – a social media account used for recruiting and engaging with incoming freshman students at UCLA – and analyzed a myriad of demographics from each post.

Our main goal from this cultivation of data was to analyze the topicof linguistic strategies used to engage prospective students and to comprehend how language choices reflect broader communicative goals in higher education and social media outreach. The method of data collection, a quantitative content analysis where we carefully recorded and studied language patterns in social media posts, focused on a 200 sample from the largerpopulation of the account and looked at gender (male/female), the opening style used (how they greet the people seeing their account, e.g., hello, hiii, hey, etc), any slang used (things like words in all caps, pls, wanna HMU, roomie, foodie, insta, etc), if there is a presence of emoji use, proper grammar and punctuation, if students listed their pronouns, if people used all lowercase or all uppercase, and their intended major (pre-med, humanities, STEM).

Since we examined different styles of speech, we also drew from the idea of language variation, which looks at how people’s language changes depending on their background, age, gender, or community involvement, as well as grammar, tone, and word choice (Bahtina, 2025).

Our data collection specifically focused on the first 200 posts chronologically available on the account at the time of data collection to ensure that we cultivated a large but manageable sample representing not only a multitude of academic disciplines but also genders, communication styles, and decisions. This approach allowed us to gather a wide variety of people at different stages of the student admission process and people from an abundance of different demographics, which helped ensure an accurate sample of the representation.

When reporting findings on gender in our study, the results were strictly based on the first 200 posts from the class account, and we did not assume a 50/50 gender split. This was because we wanted to limit any confounding variables and stay stable with our procedure and data collection, and it also revealed the prevalence of social media use and how it differs across gender.

Results and Analysis

After each group member cultivated data from the posts of the class of 2029 Instagram account we found the following findings: 43.1% of female students use emojis compared to only 32.6% of male students (Figure 2, 3), female business economic majors are 50% more likely to use slang compared to men, women are 1.8 times more likely than men to write in lowercase (Figure 1), and men in humanities adhere most strongly to formal digital norms. A key concept shown here is also the informalization of language, which posits that communication tendencies on social media tend to vary in regard to their casual and playful tone (Natsir et al., 222). This is evident in the use of emojis, lowercase letters, and slang in social media posts (Figure 1).

Figure 1

From this data we had several findings – what appears to be a casual introduction or captioning on an introductory Instagram post is often a strategic act of self-presentation that differs among each person depending on their own demographics and the image they want to illustrate to the people viewing their posts which could be future friends, roommates, classmates, or even project mates in a class setting like this. Simply put, the data shows the presence of gendered linguistic performance (Van Herk, 101). This refers to the idea that is not something we simply are but something we do, which relates to the evidence because it emphasizes the presence of linguistic performance and ways people perform. While we found relationships between gender and linguistic decisions and major and self-presentation, the relationship between gender and major was much more complex than a clear pattern.

Every individual use of emoji, lowercase letter, or slang word differs person to person (however, there are more common themes seen in some demographics than others) and demonstrates some aspect or other about a person. These posts on the Instagram account aren’t just digital information, but they have the power to reflect someone’s identity, culture, and origin. Aligning with the idea that emojis are a form of cultural expression. As Professor Junnifer Prough says, emojis clearly display layers of cultural communicative meaning, explaining that users use emojis to be understood and for belonging (Ted Talk by Freedman, 2019). When students post their introductory bios, they are engaging in a form of visual and linguistic identity making, whether they choose to or not.

Figure 2

Figure 3

These results and implications are imperative to helping illustrate how social norms shape larger themes across digital communications and reinforce the identity that language is performative even in the most casual of settings.

These students engage in what is known as “front stage” performances where they craft online personas that balance authenticity, approachability, and cultural fluency within the norms of the current contemporary society and how Gen Z acts in the current state of the social media culture. The agentive behavior is consistent with research that shows the use of social media to develop self-presented messages tailored to specific audiences, shaping their identity even before arriving on campus (DeAndrea et al., 2011).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our analysis of the UCLA Class of 2029 Instagram posts shows the language in Instagram posts as a form of digital identity construction. While captions appear to be informal, they actually reveal a choice that every single student makes in order to express themselves. They do this in order to, in some way, fit in or stand out. The use of emojis, punctuation, and slang in order to differentiate genders, majors, and regions shows that language use is made purposefully. The pattern that was most clear to us was gender-based differences in tone and formatting of the posts. Female students, when compared to male students, overwhelmingly use an informal style of using emojis, lowercase, and slang. Males, on the other hand, were more likely to have proper grammar and tone. This is clear in the research with sociolinguistics showing women often are more linguistically innovative in language to build social standing than men, who look toward status-oriented forms of communication. The difference between majors was also an interesting point where humanities students had more flexible tones and relaxed language, while STEM students were direct. This shows how different disciplines socialize students into a variety of ways in which they communicate. These posts are not only explaining who they are or what they are excited for, but they also create a performance of sorts with the things they put within the text caption of their posts. The slang, punctuation, and emojis all say something about the way in which the students desire to be seen as they matriculate.

References

Bahtina, D. (2025). 2A Variation in language. Communication 188B.

DeAndrea, David C., et al. “Serious Social Media: On the Use of Social Media for Improving

Students’ Adjustment to College.” The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 15, no. 1,

2012, pp. 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.05.009.

Freedman, A. (2019, April 26). The culture of emoji. ??? | Alisa Freedman | TEDxUOregon. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U1QpAUhnoWE

Natsir, Nur, et al. “The Impact of Language Changes Caused by Technology and Social Media.” Language Literacy: Journal of Linguistics, Literature, and Language Teaching, vol. 7, no. 1, 2023, pp. 220–28. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9216/d49e850423f6d38e416694724061649445ec.pdf.

Van Herk, G. (2018). Gender. In What is sociolinguistics? (2nd ed., pp. 96–116). Wiley Blackwell.

Duggan, Maeve. (2013, September 12). It’s a woman’s (social media) world. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2013/09/12/its-a-womans-social-media-world/