Zoe Willoughby, Anton Nogin, Isaiah Sandoval, Maria Becerra

As bilingualism becomes increasingly prevalent in a wider variety of television shows, sociolinguistic analysis of what code-switching entails and why it is used becomes even more important to look at. We delve into an analysis of the shows Dora the Explorer and One Day at a Time to explore what types of code-switching are used for audiences of different ages. We hypothesized each show would differ in its most frequent type of code-switching – metaphorical or situational – because of the different language complexity levels depending on each intended age group. However, we realized these labels may not be as clear as expected. As we analyzed the data, some instances could fit under both of those categories or did not fit under either. Since the language use was more complex in One Day at a Time, so was the categorization of the reasons why code-switching was used. We ultimately determined cut-and-dry labels such as “situational” and “metaphorical” are not sufficient enough to classify why people code-switch. In order to recognize code-switching as a tool used to demonstrate language mastery and not convenience, our analysis of the results looks to offer possible solutions to further classify these instances of code-switching in TV shows.

What’s this all about?

Along with the growing bilingual population in the United States, there has been a shift in the way bilingualism is represented in the media, especially in television shows (Grosjean 2018). In this study, we wanted to look at the layers of language complexity of bilingual speakers through bilingual shows. Given bilinguals might have another layer to add to the technicality of their speech – code-switching – it is important to see how the media portrays that. Code-switching itself has layers of complexity when it comes to explaining why a speaker might do so.

Bilingual shows are becoming more mainstream for viewers of a wider age range, producing shows such as Dora the Explorer (DE) and One Day at a Time (ODT), the two shows we focus on in this study. We used these two shows as a lens through which we viewed the reasoning behind why bilinguals might use code-switching and the context in which these switches occur. By distinguishing between the two intended age groups for each show, we decided to focus on the different types of code-switching that may be more specific to each age group: metaphorical (using code-switching as a resource to enhance meaning) and situational (using code-switching depending on topic or other speaker) (Van Herk 2018, pgs. 151-152).

We hypothesized situational code-switching would be more frequent in DE, the show for younger audiences, and metaphorical code-switching would be more frequent in ODT, the show for older audiences. After analysis, we proved this true but found that classifying reasons for code-switching would require more categories to encompass its complexity.

What’s the context?

Our research focuses on bilingual television shows, specifically ones whose characters code-switch (CS) between Spanish and English. Despite incorrect assumptions that bilingualism always means total proficiency in two languages, this neglects to acknowledge the complexity of language use for those who are multilingual (Grosjean 1994). This definition is unclear, but CS helps to show bilingualism and is indicative of a speaker’s command over the language they are speaking (Bullock & Toribio 2009).

The types of code-switching used in these shows are our central linguistic variables. Metaphorical CS is a resource used to supplement the meaning of a certain word or phrase by tapping into the associations with a certain language (Woolard 2004). Situational CS occurs when a speaker uses a different language for a certain conversation topic or with a certain speaker (Gumperz 1977). Situational CS tends to occur intersentential (within a sentence) and metaphorical CS tends to occur intrasentential (over multiple sentences), and since intrasentential CS is linked with a better mastery of a language, metaphorical CS is implied to be a sign of that as well (Bullock & Toribio 2009).

How did we go about it?

In the first three episodes of each show’s first season, we recorded each instance in which the speakers switched from English, the main language of each show, to Spanish, the secondary language. Each show has a different age recommendation, and Common Sense Media, an advocacy group that reviews the appropriateness of media for families and children, stated that Dora the Explorer (DE) is intended for audiences ages three and up, and One Day at a Time (ODT) is intended for audiences ages 12 and up (Herman 2004, Slaton 2016).

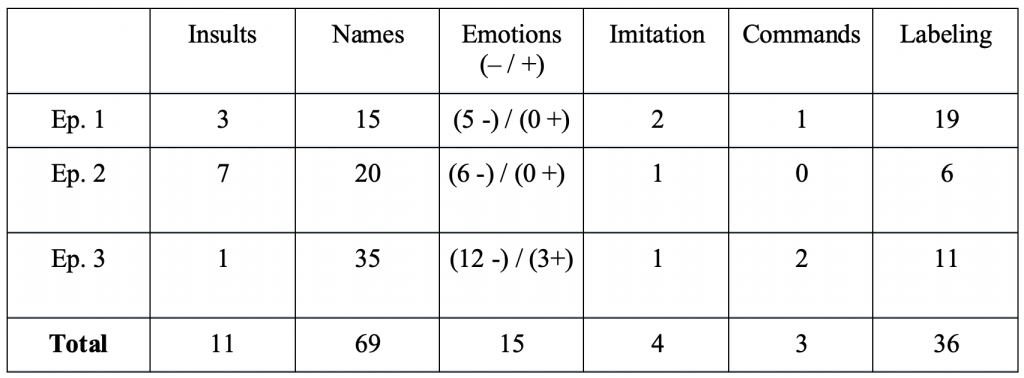

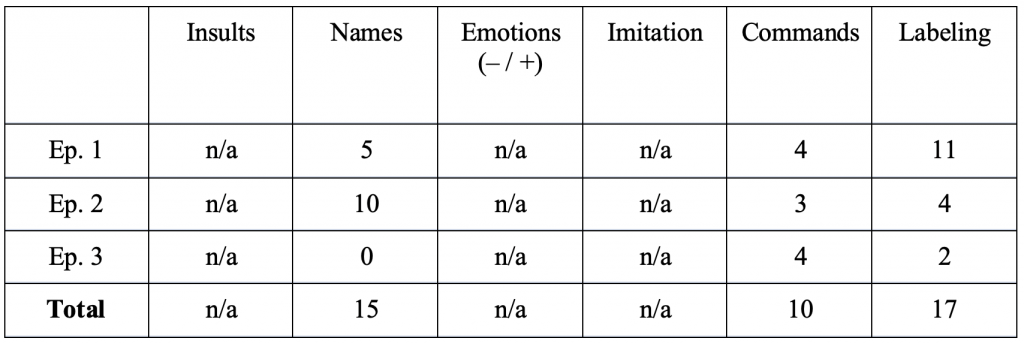

Our first step in collecting the data was to keep a running list of each instance of code-switching that occurred in each show. Along with the timestamp of the occurrence, we also included a brief description of the context in which we found the example. Once each instance was recorded from all of the episodes, we created six categories that grouped the different contexts in which CS happened. These contexts included insults, names (character called by relationship name), emotions, imitation (copying what someone else said in a different manner), commands, and labeling (calling certain things with their corresponding names in one language).

Originally, we planned to use these contexts to help us divide the CS occurrences into situational and metaphorical explanations, but this proved much more complex than expected. In order to compensate for the lack of coverage the explanations of situational and metaphorical CS gave, we created additional categorizations, which included lexical gaps (when speakers use words in one language that cannot be directly translated with the same weight), overlaps (combine multiple explanations), and exceptions (where CS did not serve as significant of a sociolinguistic purpose).

What did we find?

As we had predicted, there were more instances of situational CS in DE than there were in ODT, and there were more instances of metaphorical CS in ODT than there were in DE. For example, in ODT episode two (18:05 – 18:20), Penelope (in bold) is talking to her coworkers and boss in the office (none speak Spanish):

But maybe you didn’t hear because you were on your phone like now Uh, what? Yo voy a matar a este hombre [I am going to kill this man] Huh, what does that mean? I am just thinking about lunch.

In this example, Penelope is angry at the situation at her work and chooses to switch to Spanish to express her anger. This is a metaphorical instance because Penelope is trying to create distance between her and her coworkers.

On the other hand, DE provides clear instances of situational CS. For example, in episode two, when Dora met with Baby Blue Bird (who is monolingual), she has to switch over to Spanish to be able to communicate with him (Dora in bold):

Where do you live baby bird? ¿Que? [What?] Oh, Baby Bluebird speaks Spanish (at the audience) ¿Donde vives? [Where do you live?]

This example is situational CS because one of the speakers is only able to understand Spanish. Therefore, the situation calls for Dora to switch over to Spanish to be able to communicate.

Our hypothesis was based on the fact that DE would have less complex language usage and that ODT would have more complex language usage because of their respective intended audiences. This observation was confirmed when collecting data. We have summarized the contexts of CS for each of the shows per episode in Table 1.1 and Table 1.2 below.

From observing the contexts of CS for both shows, it is noticeable that ODT has more complexity in CS than DE. Because of the lower level of language complexity, DE has no instances of insults, emotions or imitations, meaning that classifying the reasons for CS for ODT was not as clear as for DE. In some cases, a given instance of CS did not fall neatly into metaphorical or into situational. This is when we resorted to our additional categories of why a speaker might code-switch: lexical gap, an overlap, or not clear enough for any category (exception). For example, in ODT episode one, the grandma says:

You need to do something about this little sinvergüenza [You need to do something about this little ___________]

In this case, the word “sinvergüenza,” refers to a person who is not ashamed of doing something that is seen as shameful. However, there is no direct translation in English that has the same meaning, and therefore we have labeled it as a lexical gap.

Another example of the categories we have created is in ODT episode three when the grandma says:

She thinks she’s tan fancy because her four grandsons are altar boys. Guataca. [She thinks she’s so fancy because her four grandsons are altar boys. _______]

Here, the grandma is using an insult in Spanish. This word has no direct translation to English so we have labeled it as a lexical gap. However, it is also an instance where the speaker (the grandma) is trying to create distance between her and the person she is insulting, therefore it is metaphorical CS. Since this CS instance has aspects of both lexical gaps and metaphorical CS, we labeled it an overlap.

Sometimes we couldn’t fit the CS instances into any of the categories because there seemed to be no significant sociolinguistic purpose. An example of this is when Dora repeats a word in Spanish and English a few times to teach a new word, which we labeled as repetition. Another instance is mixing, which is done often by the grandma in ODT. To clarify, we defined mixing to be when a word is used in a different language (usually intrasentential) but can be directly translated into English; CS might have happened just out of convenience. For example, in one episode, the grandma says “café con leche” which translates directly to “coffee with milk.” Also, when calling someone by their relationship name in Spanish, such as “mami” or “abuelita,” there is little to no sociolinguistic meaning behind it (we labeled this naming). Imagine this: If CS did not happen in any of these examples, would it make a sociolinguistic difference? In these cases, the speakers chose to CS for a reason that can’t be explained by sociolinguistics. In other words, the sociolinguistic difference was not enough to warrant another category.

What does this all mean?

If we only look at the scope of our hypothesis, then we proved the main points: There is more metaphorical CS in ODT, and more situational CS in DE, both suitable for each show’s recommended age group. However, the hypothesis itself did not allow us to take into account the other types of language use related to CS that came up in data collection and analysis. In every instance, whether it be a simple word or phrase repetition in DE, or more dynamic instances of CS in ODT, the words or phrases from Spanish utilized in English (or vice versa) were grammatically sound, even if they had no direct equivalent in the other language. This phenomenon shows that bilingual individuals who utilize CS are, at the very least, capable in both languages. Characters in both shows were able to switch seamlessly from one language to the other, maintaining grammaticality and conversation flow at the same time. What this means is that depending on a speaker’s frequency of CS usage, CS itself could act as a marker of high proficiency in, or even mastery of two languages.

Our hypothesis and initial conclusion stemmed from the narrow definitions of CS provided in our class textbook. The textbook provided context and examples for how metaphorical or situational CS each functioned in an interaction. However, it presumes these categories are limited by where in the phrase or sentence the CS instance occurs. The book defines situational CS as only occurring from one sentence to the other, and metaphorical CS as occurring within a single sentence (Van Herk 2018, pg. 151-152). Although the book connects language proficiency and emotional states to CS usage, it uses narrow descriptions for the phenomenon itself.

The textbook also assumes metaphorical and situational CS are the only two categories of CS worth noting. While the textbook works to dispel language myths by defining the sociolinguistic reasons for CS, it could confuse readers that there might only be two main reasons, just like it did for us. To that end, the exceptions and overlaps from our data are defined as such because we couldn’t place them in either category. It’s up to readers like you to go back and define these instances however you see fit.

What’s next?

Since there is a wide variety of other bilingual media out there (reality TV, movies, podcasts, etc.), more data could be collected to find different examples of diverse bilingual speech patterns. We could even compare media across time periods to measure frequencies of CS across several years or decades. This all ties back into one observation – that bilingual individuals are being engaged with in mass media and are being positively validated.

References

Bullock, B., & Toribio, A. (2009). Themes in the study of code-switching. In B. Bullock & A. Toribio (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-switching (Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics, pp. 1-18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511576331.002.

Grosjean F. (2018). Psychology Today, The Amazing Rise of Bilingualism in the United States. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/life-bilingual/201809/the-amazing-rise-bilingualism-in-the-united-states.

Grosjean, F. (1994). Individual bilingualism. The encyclopedia of language and linguistics, 3, 1656-1660. http://www.signwriting.org/forums/swlist/archive2/message/6760/Indiv%20bilm.rtf.

Gumperz, J. J. (1977). The Sociolinguistic Significance of Conversational Code-Switching. RELC Journal, 8(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368827700800201.

Herman, J. (2004, December 14). Dora the Explorer – TV Review. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/tv-reviews/dora-the-explorer.

Slaton, J. (2016, December 19). One Day at a Time – TV Review. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/tv-reviews/one-day-at-a-time-0.

Van Herk, G. (2018). Multilingualism. In Gerard Van Herk (Ed.): What is sociolinguistics? (2nd edition: pp. 146 – 157). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Van Herk, G. (2018). Glossary. In Gerard Van Herk (Ed.): What is sociolinguistics? (2nd edition: pp. 220 – 237). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Woolard, K.A. (2004). Codeswitching. In A. Duranti (Eds). A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology (pp.73-94). Oxford, Blackwell. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470996522#page=92.