Vivian Ha, Hannani Ryan, Padilla Pallares Gudalupe, and Trivedi Risha

Why do Gen Z guys confidently drop a “bet” while girls jokingly flex their “Rizz”? We could just say that it’s because we live in an age where language spreads through trends and group chats. However, slang is more than just a way of sounding cool; it’s a tool for performing identity. This blog post aims to explore how Gen Z women and men (ages 18-25) who regularly use smartphones and are active on TikTok differ in their use of slang words and how it might reflect broader traditional gendered communication patterns. We ask: Do Gen Z women and men use slang differently in their communication, and are these slangs a form of gendered communication? We hypothesize that Gen Z slang reflects broader gendered communication patterns, with certain terms showing traditionally feminine or masculine traits. At the same time, we emphasize that communication is fluid and inclusive. This blog will provide insights into how emerging slang trends reflect deeper attitudes about gender, with the influence of the media.

Introduction and Background

Generation Z (“Gen Z”) is often seen as the generation that is constantly challenging traditional norms, especially when it comes to how they speak. Over the past couple of years, TikTok has been a cultural dominant, where slang spreads rapidly and often carries deeper meanings about identity, relationships, and culture. Prior research has explored gender differences in communication; however, they have mostly focused on face-to-face or text-based interactions. We believe that far less is known about how gendered language plays out in fast-moving, algorithm-driven spaces such as TikTok. Hence, what led us to conduct this research, our target group consists of Gen Z women and men ages 18-25 who are active users on TikTok. We specifically selected TikTok due to its platform population hosting more Gen Z individuals than others, and due to the constant exchange of slang on its platform. Common linguistic features of Gen Z include shortened words and abbreviations such as “sus”, for suspicious. Other linguistic features present include gendered slang phrases that reinforce traditional gender expectations, such as the terms “girl boss”, “I’m just a girl”, “sigma male”, etc.

Some academic sources we view to be relevant to our topic include Van Herk’s “What is Sociolinguistics?”, which focuses on differences between gender interactions and communication. Herk explains that gendered language is not natural but performed, since gender is a social construct. He also points out that women most commonly use hedges, fillers, tag questions, uptalk, etc, that reflect differences in the way women and men communicate. In comparison, men tend to be more assertive and interruptive. This source helps us understand the roots of gendered communication so we can then compare it to modern slang use and its relation to gender. Another source we are closely looking into is, “The Social Significance of Slang” by Alice Damirjian. This article argues that slang use is deeply tied to identity formation, group boundaries, and social cohesion. While it doesn’t focus on the meaning of slang words, it instead explores how words are used and in what context. This method is similar to what we intend to do in our research paper, and why we viewed this source as a vital informative piece.

Additionally, A.M. Blackstone’s “Gender Roles and Society” article explores how gender roles are learned and reinforced through socialization and institutions. This citation we included since it helps us support our hypothesis that Gen Z slang may reflect gendered communication patterns. Blackstone’s sociological framework on gender and identity is a great source that guides our research and analysis, based on empirical evidence rather than assumptions. Overall, these studies have helped us inform our hypothesis that argues that while slang is fluid and not fully tied to gender, slang use still echoes traditional gender norms.

Methods

Our study investigates how Gen Z men and women use slang on TikTok and whether this reflects broader gendered communication patterns. To explore this, we will collect slang terms through a survey and then analyze how those terms are used in TikTok videos using a fresh account to eliminate algorithmic bias. The survey will be hosted on Google Forms for ease of delivery and to ensure that we have access to necessary statistics. After this survey, we will examine the top videos for each slang word. The use of both individual and broad-scale analysis techniques allows our group to build a more nuanced understanding of the use of slang.

Once this stage of the research process has been completed, we will be aiming for 10 videos per slang term, which will offer us dozens of relevant examples through both the video itself and its comments. This number is a reasonable amount to reach, but it does not limit our understanding. We chose this two-prong data collection method to more accurately depict the results of this experiment and gain a deeper understanding of the language used.

Using thematic coding and discourse analysis, we will analyze tone, context, delivery, and nonverbal cues associated with each slang term, focusing on how language use relates to gender performance and identity. The discourse analyzed will be specifically the way that the different genders choose to interact with each other using the slang presented. Our guiding research questions include: Do men and women use the same slang terms differently? What patterns of gendered communication emerge through slang? And how do these trends reflect or challenge traditional gender norms? Based on existing sociolinguistic literature, we hypothesize that Gen Z slang use mirrors gendered communication tendencies, with women more likely to use slang that signals inclusivity and emotional connection (e.g., “slay”), and men more likely to use slang that emphasizes assertiveness or dominance (e.g., “let’s go”). However, given Gen Z’s fluid approach to identity and language, we also expect to find challenges to this norm.

Results and Analysis

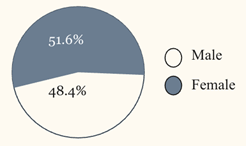

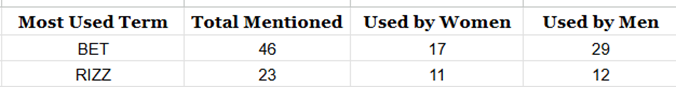

Our final pool of participants for the Google survey portion of data collection was 91 responses, with 51.6% male and 48.4% female respondents. We found that “bet” and “rizz” were the two most frequently used slang terms. The term “rizz” was the most frequently used, with it being mentioned a total of 46 times between 17 women and 29 men. While “bet” came in second, with it being mentioned a total of 23 times between 11 women and 12 men.

Figure 1. Results from the Google Form Survey: Total Number of Respondents was 91

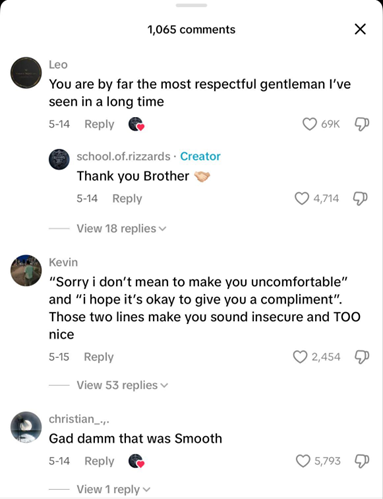

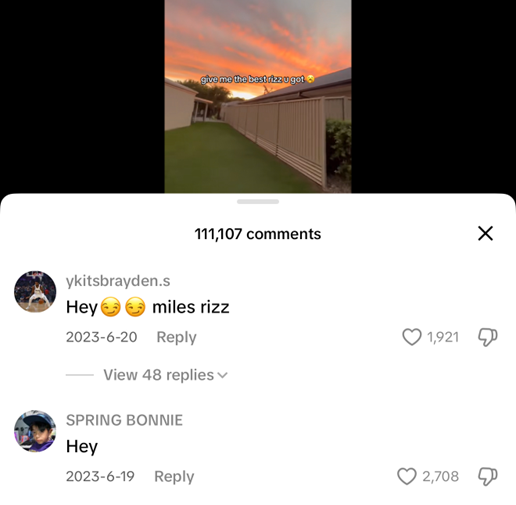

When analyzing the 10 male-coded videos for “rizz”, 8 out of 10 videos generated by male content creators were men demonstrating their “rizz”, by approaching women with a flirtatious attitude, with the goal of receiving the woman’s contact information. While 4 out of 10 videos captured men providing advice on how to have “rizz” or “rizz up” women. This suggests that men’s use of the term “rizz” aligns with traditional masculine traits like assertiveness and confidence in social situations. It reflects Gen Z’s tendency to blur sincerity and parody, where young men both conform to and mock traditional courtship behavior.

Figure 2. Contextual Use of “Rizz” by Gender (Male: Flirtation, Confidence)

As for the female-coded videos for “rizz,” the results demonstrated that women most often used “rizz” for humor and romantic advice, sometimes expanding it beyond male-female contexts. The data suggests they intentionally adopt masculine slang to relate to men and navigate social dynamics, which reflects how gender norms shape communication even with shared slang. In addition, the data also showed how women resisted gendered dynamics by using “rizz” in a different manner than it was intended.

Figure 3: Contextual Use of “Rizz” (Female: Romantic Advice)

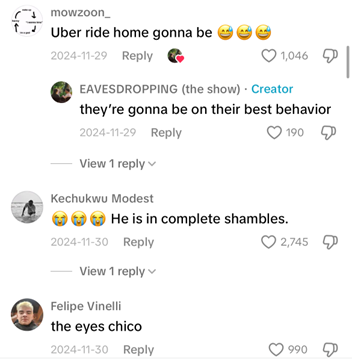

For the 10 male-coded videos with the slang term “bet,” we found that men most frequently demonstrated or recorded their use of “bet” to express agreement, acceptance, or commitment to a plan, e.g., responding “bet” when a friend proposes hanging out or making a wager. 5/10 videos analyzed showcased scenarios where “bet” was used to confirm plans or signal confidence in accepting challenges. This result suggests that men tend to use “bet” as a casual, assertive way, aligning with traditional masculine traits of confidence and decisiveness. It also reflects Gen Z’s conversational style, which blends casual affirmation with a sense of underlying confidence.

Figure 4. Contextual Use of “Bet” by Gender (Male: Agreement, Commitment, Confidence)

As for the 10 female-coded videos for the term “bet,” Our results showed that women most often used “bet” to express agreement, excitement, or playful sarcasm in casual conversations with friends. 3/10 videos analyzed women using “bet” in a lighthearted or humorous way. Showing enthusiasm or signaling they were on board with a plan.

Figure 5. Contextual Use of “Bet” by Gender (Female: Sarcasm, Excitement, Agreement)

Discussion and Conclusion

Our results show that there are distinct gendered patterns in the use of slang terms like “rizz” and “bet.” For the slang term “rizz,” men were more likely to demonstrate or embody the term, while women often used it mockingly or humorously. In the case of “bet,” men tended to use the term to affirm plans or accept challenges, reflecting direct engagement, whereas women used it more playfully or sarcastically. For both slang terms, men typically expressed traditionally masculine traits such as confidence, assertiveness, and decisiveness. In contrast, women exhibited traits like humor and irony as a way to challenge or resist the gender dynamics ingrained in the slang terms. These insights are particularly useful for scholars in sociolinguistics, digital media, and gender studies, as they highlight how informal language can reinforce, challenge, or reshape traditional gender roles. By looking at how terms like “rizz” and “bet” are used, we can gain a better understanding of how digital media reflects and reinforces ideas about traditional gender roles and communication. Our results could benefit researchers, educators, and media literacy advocates by shedding light on gendered communication patterns embedded in Gen Z slang. This insight can contribute to a broader conversation about how digital culture affects youth identity formation, peer dynamics, and societal expectations. Our research helps unpack the cultural significance of everyday language, positioning it as a key site for both reproducing and potentially resisting dominant gender ideologies.

References

Bibian Ugoala. “GENERATION Z’S LINGOS on TIKTOK: ANALYSIS of EMERGING LINGUISTIC STRUCTURES.” Journal of Language and Communication, vol. 11, no. 2, 30 Sept. 2024, pp. 211–224, www.researchgate.net/profile/Bibian-Ugoala/publication/384965246_GENERATION_Z, https://doi.org/10.47836/jlc.11.02.08.

Blackstone, A. (2003). Gender Roles and Society. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/soc_facpub/article/1000/&path_info=Blackstone___Gender_Roles_and_Society.pdf

Damirjian, A. (2024). The social significance of slang. Mind & Language. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12530

Herk, G, V. (2018). What Is Sociolinguistics? (Linguistics in the World) 2nd Edition (1). India New Delhi: Wiley Blackwell.

Jahan, I. (2021). The impact of gendered language on our communication and perception across contexts and domains. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 17(4), 3523-3534. https://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/5449