Hashim Baig, Siuzanna Shaanian, Georgia Lewis, Jacob Cook, Christian Atud

The rise of English as the global lingua franca has had profound effects on multiple cultures worldwide. One such spot is the Indian subcontinent, especially with the emergence of India from centuries of colonial rule. This paper looks at how Hindi-English code-switching (popularly called Hinglish) in Bollywood films post-2000 both reflects and constructs social identities. It analyzes five contemporary Bollywood films and argues that the increase in Hinglish usage corresponds with characters’ social mobility, still signifying English as a potent symbol of prestige. This research aims to unearth the interplay of dynamics between language usage and perceived social standing in contemporary Indian cinema.

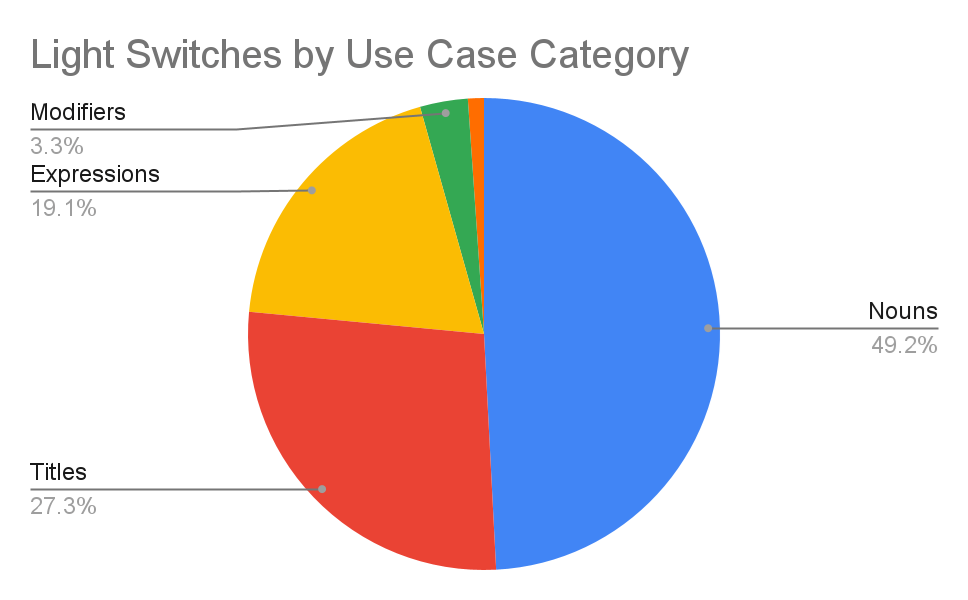

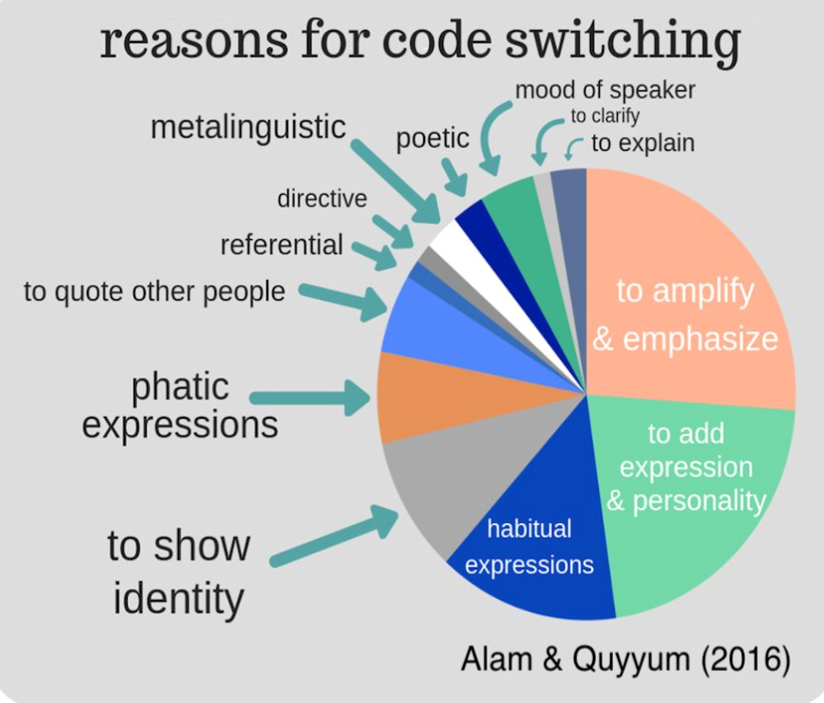

Introduction English, being a global language, has influenced many cultures worldwide. One of the most impacted cultures was that of India, a former British colony. One of the most exciting consequences of this influence is the rise of Hinglish — a mixture of Hindi and English — primarily in the context of Bollywood films. Our project will investigate how Bollywood movies use Hinglish as a means of social change by depicting a character as having a higher social status through excessive code-switching into English. Background Bollywood is the leading film industry in India, providing fertile ground for the use and experimentation of different languages and linguistic expressions. The most salient is the integration of English into Hindi dialogues, often called Hinglish. This is relevant since some of the more recent films with this thematic feature in the foreground also depict the interaction between the English and Hindi languages as facilitators of social mobility. The fact that English is the prestigious code in Indian society and Bollywood is very influential in molding cultural trends, thus marking these films as good starting points for studying linguistic portrayals of social mobility. Literature Review and Context The Colonial Hangover The continuing popularity of English in India began during the British colonial era, when the English language was used in administration and education. Within this context, the English language symbolized both sophistication and higher social status. Chandra (2014) says that in recent times, English has become a fashionable aspect of filmmaking in India, “associated with modernity and prestige.” Chakraborty (2022) also mentions what he refers to as the ‘Colonial Hangover.’ Knowledge of English, he says, is equated with higher social status and respect. Bollywood’s Linguistic Landscape Even in their language use, Bollywood films reflect changes in society. According to Rao (2010), English is identified with modernity and prestige; Hindi, however, is an intimate language of traditional values. Furthermore, this dichotomy has been depicted using code-switching. Context and social aspirations govern the switch between Hindi and English. Code-Switching as a Tool of the Narrative Si (2011) holds that code-switching is not random but rather a narrative device in Bollywood movies. English words or phrases are inserted into Hindi dialogues to portray a character’s social mobility, education, or cosmopolitanism. The present paper seeks to understand how, drawing from these studies, such linguistic choices could potentially stand synecdochally for social mobility in contemporary Bollywood films. Project Design This paper endeavors to examine and find evidence of any relationship that may exist between patterns of code-switching and the rise and fall of the characters’ social status in five films: Thank You for Coming (2023), Sukhee (2023), Laapataa Ladies (2023), Mission Raniganj: The Great Bharat Rescue (2023), and 3 Idiots (2009). The reason these movies have been selected for this purpose is that they essentially belong to a genre of ‘rags-to-riches’ stories and because they have been widely viewed. Methodology Collectively, we utilized a mixed-methods approach; qualitative content analysis was combined with quantitative frequency measures. We analyzed under what context code-switching occurs. That is, for particular scenes, social interaction and visual information related to socioeconomic status. We also counted the frequency of code-switching. We grouped each instance of code-switching into one of two categories: light and heavy. Light code-switching refers to sporadic insertions and alternations of English into Hindi, as well as forms borrowed from English. Heavy code-switching would refer to the use of extended English expressions, sentences, and rapid switching between English and Hindi. Each instance was counted across different narrative stages: exposition, rising action, climax, and falling action. Hopefully, through such an examination, we may develop insight into how Hinglish use is representative of social identities and how code switching shapes them in Bollywood films. Results and Analysis In this research, we found that there was a moderate use of light phrases in middle socioeconomic environments, with much more frequent usage towards and between people in high social positions. Light phrases are pervasively used in these environments and are almost entirely used for referring to specific items such as “boreholes” or “walls,” as well as specific titles such as “Sir” or “Doctor.” In this study, the average amount of light utterances per movie totals to around 400 phrases. Of those 400 phrases, about 25%, on average, include non-noun switching. This subset mostly consists of expressions/sayings (e.g., ‘Thank you,’ ‘I’m sorry’) and modifiers (insertion of adjectives, adverbs, etc.). Of the nouns, it is worth noting that a majority of these utterances are a form of borrowing from western culture. These include scientific/official names (e.g., ‘Carbon Dioxide,’ ‘Instagram’) and specific titles (e.g., ‘Doctor,’ ‘Sir,’ ‘Upper Management’). In especially institutionalized contexts, such as in educational or professional settings, this tendency is much more pronounced, as it would correlate with intelligence and competency. It is akin to using proper jargon when in an official discussion between peers or co-workers. Although nouns and titles share similar linguistic qualities, a distinction must be made between the two in order to account for their differing use cases. Titles, in particular, were commonly used towards individuals of high standing as a form of politeness and respect in a professional setting. One of the most common examples of this would be the usage of the word ‘Sir’ towards high ranking individuals. It is also worth noting that verbs were more commonly used in heavy switches and see little to no usage in light switches. This is largely due to the usage of English verbs in command/directive phrases rather than as a simple insertion/alternation. Most commands would be issued by an individual with authority and power. This would lead to the switching of the entire sentence to English, which would give the order a more serious/official connotation and allow the individual to leverage their position. In regards to heavy code-switching, we observed 40-70 instances of heavy switching per movie, on average. This number would fluctuate depending on the overall setting of the movie. Movies set in professional settings, such as Mission Raniganj, would see a higher usage of heavy code-switching as a marker for ‘officiality.’ This trend exists because a much larger cast of characters are depicted as ‘intelligent’ and ‘powerful’ enough to use these forms. Heavy-switching forms can also be split into several categories: extended sayings/proverbs, official conduct, and narrative effect. The frequency of each category would also depend on the movie genre, with action movies opting for more instances of official conduct. Official conduct, in this study, would be a character’s tendency to use English as a medium to denote seriousness, power, and hierarchical respect. Medal ceremonies, press conferences, and board discussions would include many instances of ‘official’ code switching. Usage of English for narrative effect would mostly be tied to specific characters as part of one’s personality and could be used to highlight/exaggerate a powerful point during the movie. Such instances include the usage of English to look cool, smart, or funny. On the topic of sayings and proverbs, scriptwriters would use large English expressions to flesh out a specific character’s identity. One character, for example, would use the expression “I know this place like the back of my hand” as a catchphrase to denote professionalism, while also being entertaining for the audience. Another interesting finding includes intentionality when switching between English and Hindi. We found several instances where rapid switching between English and Hindi would depend on the context and emotion behind each utterance. Some pivotal scenes would hinge on the differentiation between officiality and intimacy. Moments where a character must command/exert one’s authority in an official manner would invite the use of English. In moments of weakness, intimacy, and affection, characters would often switch back to Hindi. This finding runs similar to Rao (2010)’s findings, where he would describe this tendency as a “preservation of Indian values.” To demonstrate this, we can take a look at an example from the movie Mission Raniganj. In this scene, the main character, Gill, is the main rescue officer in charge of rescuing 70 miners who were trapped in the Raniganj Colliery. Gill is rich and depicted as intelligent, calm, and heroic in a majority of the scenes he appears in. The other characters in this scene, such as Director Ujwall and Director Dayal, are all well-dressed and depicted as intelligent, powerful people. In this scene, the managing board is picking out an individual to head into the mines through a borehole to help manage the manual rescue of the miners. CO2 gas is forming, making the operation potentially lethal. Director Dayal, in an attempt to steal the credit, says: “No, we can’t be so selfish; [Gill has a bright future]; we can’t send a talented officer [down to sacrifice his life].” Gill responds: “Thank you for your concern sir, but I promise you, [I will have my morning tea with you].” The blue words that are within brackets represent phrases in Hindi, whereas all other words are mentioned in English. This scene demonstrates the intentional switching between English and Hindi in an official setting. Here, we see both individuals speak in English when formulating an official response, such as Gill’s appreciation and Dayal’s request. They both, however, intentionally switch to Hindi when appealing to emotion and intimacy. This scene is powerful and successfully depicts Gill as not only intelligent but magnanimous in a way that parallels Indian values. Film Analysis Examples (Excluding the already discussed Mission Raniganj) Discussion and Conclusions India has more than a billion people. Given our small sample size of five movies, we are not able to make sweeping generalizations about code-switching in Indian society outside the context of its cinema. If we look at code-switching as a plot device used by Indian moviemakers, we are able to better understand the implicit interpretations of such language usage and thus, how it correlates with class and other socioeconomic indicators. This paper focused on several linguistic aspects of code-switching, including the syntactic category of the English words used. Overall, our statistical analysis is in line with previous findings on this topic, that is to say, that mostly nouns and titles are used in intra-sentential code-switching. References Balabantaray, S. R. (2020). Impact of Indian cinema on culture and creation of world view among youth: A sociological analysis of Bollywood movies. Journal of Public Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2405. Chakraborty, O. (2022). Prevalence of Colonial Hangover in Bollywood Movies with Primary Focus on Queen and English Vinglish. https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol10-issue5/Ser-1/G10053338.pdf. Chandra, S. (2014). Main ho gaya single I wanna mingle…: An evidence of English code-mixing in Bollywood Song Lyrics Corpora. 16(1). https://www.researchgate.net. Mahbub-ul-Alam, A., & Quyyum, S. (2016). A Sociolinguistic Survey on Code Switching & Code Mixing by the Native Speakers of Bangladesh. Manarat International University Studies, 6(1). https://www.researchgate.net. Rao, S. (2010). “I Need an Indian Touch”: Glocalization and Bollywood films. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513050903428117. Si, A. (2011). A Diachronic Investigation of Hindi–English Code-Switching, Using Bollywood Film Scripts. International Journal of Bilingualism, 15(4), 388–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006910379300.

Our results elucidate the social mobility aspect of English usage and code switching in Indian cinema. In the films we analyzed, those who used more English were depicted as having a higher social status, better education, and better job prospects than those who used mostly or exclusively Hindi. The lexical decisions of Bollywood script writers is pertinent in this context, as well as Indian society as a whole, given the oversized impact that these movies have on the culture of South Asia. As such, code-switching in Indian cinema is reflective of broader social perceptions of English and its associations with coolness, erudition, etc.