Korosh Bahrami

Previous research conducted on differences in interruption usage between men and women yielded inconclusive results, providing the impetus for this study. This present study seeks to explore gender differences in the usage of interruptions in mixed-sex two-person conversational style sports interviews. In addition, I am exploring whether the informal structure of a sports interview, involving frequent banter, back-and-forth exchanges, and playful talk alters the relationship between gender and interruption usage and/or leads to certain conversational phenomena. In order to do so, I am observing sports reporters engaging in turn-taking with athletes over the course of interviews that are posted on YouTube. The overall objective is to see whether or not there is a qualitatively significant difference in interruptions between men and women over the course of these interviews. In order to accomplish this, transcripts from these conversations will be analyzed using critical discourse qualitative analysis techniques. Continue reading to see what results the study was able to yield!

Introduction

Overall, up to this point in time, the research on gender-based differences in use of interruptions has not been definitive. While Deborah James and Sandra Clarke (1993) found a non-significant effect of speaker gender on interruption rates, Zimmerman and West (1975) found evidence to the contrary, mainly that in mixed-sex conversations, men engage in dominant interactive styles, ultimately resulting in more male-initiated interruptions. What is even more unclear is whether such phenomena can be seen in the world of sports, a traditionally male-dominated field. As mentioned before, this study analyzed the usage of interruptions by both men and women in two-person conversational style sports interviews. A prevailing societal stereotype is that men tend to be interrupters of conversation so I put that to the test. After conducting analysis on the relevant interviews, it was found that interviewers, by poking fun and teasing, threatened the negative faces of the interviewees, prompting a response by the interviewee intended to lessen the blow of the teasing.

Methods

Two YouTube videos (one being an interview of LeBron James by Rachel Nichols in May 2018 and one being an interview of Serena Williams by Andy Roddick in September 2013) were viewed. Transcripts were then created for relevant dialogue across the two videos and then analyzed using a critical discourse analysis (CDA) approach, primarily keying in on turn-taking moments. Standard transcript guidelines were followed.

Results

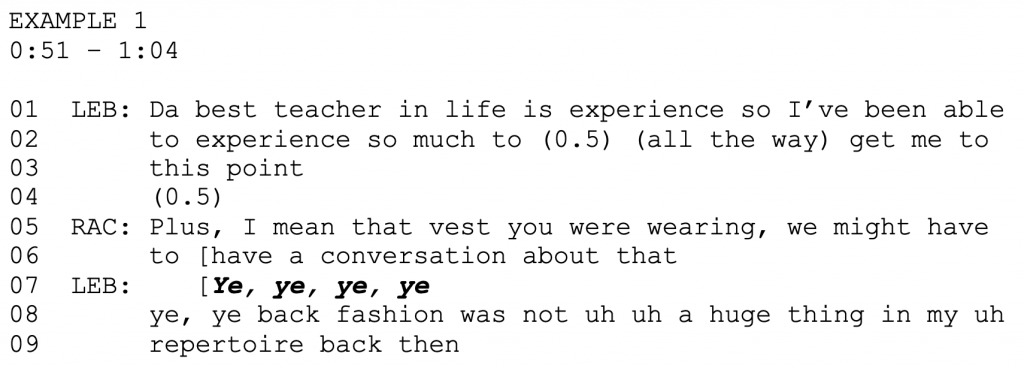

In the following conversation, Rachel Nichols and LeBron James discuss LeBron’s 9th trip to the NBA Finals shortly after LeBron’s Cleveland Cavaliers won the Eastern Conference. The first interruption happens when Rachel pokes fun at LeBron’s teenage fashion choices:

Taken from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSyyd4CgIBY

Towards the end of her turn, Rachel playfully bringing up LeBron’s decision to wear a vest in lines 5-6, at which point LeBron begins speaking, leading to temporarily overlapping talk which ends when Rachel cedes talking while LeBron continues to do so. Because LeBron broke in at a point in the conversation that cannot possibly be taken as an appropriate place for a transition (Sacks et al., 1974) and he increases the amplitude of his voice as he breaks into the conversation, this would be considered an interruption. In lines 8-9, LeBron seemingly backs himself up on why he wore a vest, pointing to the fact that he was a different person then than he is now. By interrupting, LeBron does not allow for Rachel to tease him anymore and further threaten his negative face, which is defined as a person’s desire for independence and freedom from imposition (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2018). Lines 8-9 in effect serve to lessen the blow of Rachel’s face-threatening act. The next example illustrates a productive overlap:

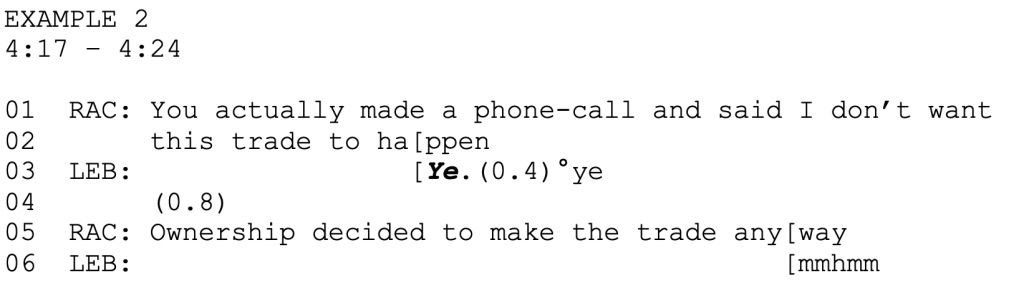

In contrast to the previous example, Rachel does not completely cede talking when LeBron begins to talk. She jumps right back into the conversation after a 0.8 second break that can be seen in line 4. Line 3 is thus a productive overlap coming at the end of a turn construction unit (TCU). It is intended to move the conversation forward and signify LeBron’s agreement with Rachel’s statements made in lines 1-2.

Going into the interview, both Rachel and LeBron know that it will be televised and broadcast globally. Consequently, face-threatening acts become magnified. A face-threatening act initiated by Rachel in this case undermines LeBron’s stature and social image on a larger scale, causing him to butt in as a defense mechanism to protect himself and his social image.

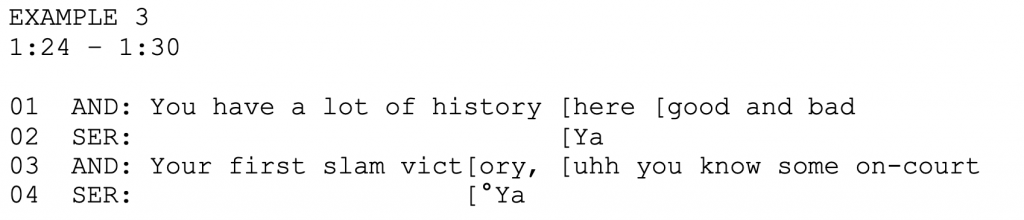

In the next conversation, Serena Williams is interviewed by Andy Roddick. Their discussion revolves around the U.S. Open:

In line 2, Serena interjects Roddick’s speech with a reassuring “Ya,” but Roddick then continues to talk, similar to the conversation documented in example 2. In line 4, Serena also interjects with a “Ya.” In both instances, as she speaks, Serena nods her head up and down and orients her body towards Roddick, illustrating the role that her body language plays in physically showing Roddick that she is comfortable in the conversation.

Taken from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSyyd4CgIBY

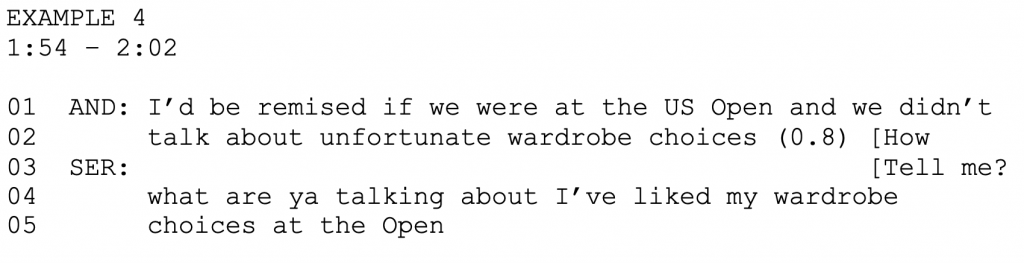

In the next excerpt, Serena and Roddick discuss Serena’s match-day style:

In line 2, after Roddick finishes talking, no one talks for 0.8 seconds, a momentary break in the conversation. Usually, gaps of around 200 ms are characteristic of the end of a turn and the beginning of a new one (Levinson & Torreira, 2015). As a result, Serena begins talking because Roddick seemingly ended his turn, eventually leading to overlapping talk. When Roddick says “unfortunate wardrobe choices” in line 2, jokingly making fun of Serena’s attire, Serena responds with a tilt of her head and opening of her mouth in surprise. Serena’s negative face is threatened. She then follows that by not backing down. Whereas LeBron went along with Rachel, Serena tries to give Roddick a chance to take back what he said by prompting him with a question in line 3. After she finishes talking in line 5, Serena tilts her head back to the right again, staring into space, a clear change in body language.

Discussion/Conclusion

CDA was inconclusive in proving whether or not there is a gendered difference in interruption usage. Interestingly, however, the manner in which the interviewees responded to the face-threatening acts significantly differed. While LeBron was agreeable, Serena remained steadfast, not giving an inch.

Overall, this study sheds light on the concepts of face-threatening acts, negative face, and social image. A face-threatening act doesn’t necessarily have to take the form of clearly hostile, aggressive words. As seen in both of the videos, it can also take the form of banter. Individuals expect their own face needs to be met and are then in return expected to meet the face needs of others (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2018). When these needs are not met, problems arise, which can hurt personal relationships.

Social image is basically society’s beliefs, thoughts, and feelings about us. When it comes to well-known public figures in the world of sports who are constantly seen in the media, their social images take on a larger than life form. Everything they do is put under a microscope, subject to scrutiny and the world of public opinion. Obviously, an individual wants to be seen in the most favorable light and therefore he/she will act accordingly to ensure this. Being the subject of the interviews, LeBron and Serena understand that it is in their best interest to be mindful of what they say.

References

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2018). Language and gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James, D., & Clarke, S. (1993). Women, men, and interruptions: A critical review. In D. Tannen (Ed.), Oxford studies in sociolinguistics. Gender and conversational interaction (pp. 231–280). Oxford University Press.

Levinson, S. C., & Torreira, F. (2015). Timing in turn-taking and its implications for processing models of language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00731

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language, 50(4), 696. doi: 10.2307/412243

Zimmerman, D. H., and West, C. (1975). Sex roles, interruptions and silences in conversation Language and sex: Difference and dominance (pp. 105 – 129. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.