Kara Bryant, Cora He, Sydney Trieu, Monrelle Wilson

This study investigated whether being bilingual is an advantage for understanding various accents and spoken English when their first language is not English. To test this phenomenon, either L1 Mandarin, L2 English, or L1 English participants listened to minimal pair audios where they were asked to answer which word they heard, as either a free response or between two choices. The minimal pairs were chosen because one sound existed in Mandarin and English, while the other sound only existed in English. It was hypothesized that L1 Mandarin, L2 English speakers would perform better than their L1 English counterparts. The results of this study supported the hypothesis and found that L1 Mandarin speakers had greater accuracy in identifying the correct phoneme, specifically, there was a greater disparity between the two groups’ accuracy with sounds that only existed in English. These results indicated that bilinguals use a broader phonological framework, which helps them to interpret non-native accents more accurately than monolinguals. This research will help increase the corpus surrounding this area of research and could potentially inform teaching methodologies in order to build upon communication in multilingual and multicultural environments.

Introduction and Background

Our project aims to investigate how accented speech affects the ability to distinguish between phonological differences and intelligibility. According to Bsharat-Maalouf et al., the listener’s comprehension can be impacted by “the production of accented or conversational speech” (2023). Comprehension is the ability to understand speech differences and contrast between minimal pairs. In episode 61: When Accents Speak Louder than Words from the podcast Undark, Chee Kiang Ewe, a researcher and professor, explained that “because of [his] accent, on top of [him] speaking fast, it was really hard for student[s] to understand [him]” (Roberts, 2022, 4:17). This is not uncommon. Therefore, we aim to investigate whether accented English has an impact on comprehension for L1 and L2 speakers of English. We will test two different groups, one with their L1 English without any knowledge of Chinese and the second L1 Chinese, L2 English. We aim to investigate whether being bilingual is an advantage for understanding various accents and spoken English when their first language is not English. Our hypothesis is that L1 Chinese speakers will perform better on the minimal pair task since they have been exposed to both English and Chinese. Furthermore, we predict that the L1 English speakers will have a more difficult time during the task because they do not have the same amount of exposure to Chinese as the L1 Chinese speakers.

Our first target group includes L1 Chinese and L2 American English speakers. The language path for these speakers often involves overcoming significant phonetic and phonological differences between Chinese (a tonal language) and English (a stress-timed language). Research indicates that L2 English speakers with L1 Chinese backgrounds typically have trouble recognizing some English phonemes that do not exist in Chinese, such as distinguishing between /v/ and /w/, /l/ and /r/, /θ/ and /s/, and /ð/ and /d/ consonants or certain vowel distinctions (e.g., /iː/ vs. /ɪ/, /ɛ/ vs. /æ/) (Li, 2016). Studies highlight that these speakers might use different cognitive processing methods to adapt their L1 phonological awareness to understand L2 auditory input (Li, Cheng, & Kirby, 2012).

Our second target group includes Monolingual American English speakers. Monolingual English speakers comprehend audio information based on the way they know English sounds and forms, using highly automatic top-down and bottom-up processing techniques (Perfetti et al., 2005). However, exposure to non-native accents, such as a heavy Chinese accent, may create unfamiliarity that can disrupt comprehension due to different speech rhythms and systematic phonological processes that differ from unaccented speech (Vandergrift, 2007). The core linguistic aspect of this analysis is phonological awareness. Monolingual English speakers naturally process these prosodic cues but may face challenges with different phonetic segments that are absent in Chinese but present in English. The study will apply a comparative analysis of listening comprehension using cognitive processing theories. Vandergrift’s (2007) model of second language listening comprehension, which emphasizes the integration of bottom-up (decoding words and sounds) and top-down (using context and prior knowledge) processes, will guide the analysis. Perfetti et al.’s (2005) reading and listening comprehension framework will further support the understanding of how the ability to process phonological differences affects overall comprehension.

Methods

The project’s goal was to see if difficult minimal pair pronunciation in Mandarin-English bilinguals had an effect on monolingual English listeners’ comprehension. To measure this, participants’ selection of the correct target phoneme between allophone pairs was measured. For Mandarin L1 speakers, there are certain sounds in English that are perceived as allophones, which they have a difficult time distinguishing between and producing. Allophones are sounds that are perceived differently between speakers. This was done to see if there was a correlation between ambiguous or unclear pronunciation of minimal pairs and listener comprehension.

To conduct this study, a survey containing six minimal pairs, or twelve words in total, was created. Minimal pairs are two words that only differ in one sound. For example, a minimal pair in English would be “bat” and “pat”. The minimal pairs were selected as English phonemes that are difficult for Mandarin speakers to produce and distinguish between. For the experiment, the minimal pairs “vet” and “wet, “rot” and “lot”, “thin” and “sin”, “they” and “day”, “beat” and “bit”, and “bed” and “bad” were used. The “th” sound in “they” and “thin” and the “v” sound in “vet are consonant sounds not found in Mandarin, and are subsequently difficult for L1 Mandarin speakers to pronounce. Additionally, for the vowels, Mandarin does not make a contrast in vowel length, unlike English. Therefore, the vowels in “beat” and “bad” are more likely to be used interchangeably with their minimal pair counterparts (Li, 2016). For the audio sample, an L1 Mandarin speaker who was still learning English as an L2 pronounced the minimal pairs. For each minimal pair, the speaker produced the target word within a sentence to eliminate the factor of the speaker hyper-fixating on correct pronunciation. However, in the survey, the participants only heard the minimal pair/target word. This was done to eliminate the possibility that the participants would select the correct word based on context within the rest of the sentence.

The Google form survey was then distributed to 33 individuals, 22 of which were Mandarin, English bilinguals, and 11 of which were English monolinguals. The bilingual individuals only had experience with English and Mandarin. While the English monolinguals had no informal or formal exposure to Mandarin. The first section of the survey focused on demographic information. This section asked participants what their L1 and L2 were. In the second section, participants were asked to listen to the audio files. For the answers, participants were randomly assigned to a restricted or unrestricted environment for providing answers. In the unrestricted environment, participants gave their own free responses. In the restricted environments, participants were provided with two options and were asked to select between the two. For the unrestricted environment results, as long as the target phoneme was realized by participants, it would be counted as correct. Based on our project design, we hypothesized that the L1 Mandarin, L2 English speakers would perform better than their L1 English counterparts.

Results and Analysis

The data reveals that L1 Mandarin and L1 English speakers struggled with certain phonemes, most recognizably /v/ as in vet, /ð/ as in “they”, and /ɪ/ as in “bit”. These specific difficulties are thought to be due to the absence of these sounds in Mandarin, which would make them harder for L1 Mandarin speakers to produce. This might also indicate increased difficulty for L1 English listeners when comprehending selected phonemes pronounced with a Mandarin accent. In the case of L1 Mandarin speakers, they displayed greater proficiency in identifying these challenging phonemes when compared to L1 English speakers, which suggests that being bilingual may enhance adaptability when processing non-native phonological contrasts. When we introduced lexical priming through a restricted-response environment, where participants chose between two options, this significantly improved phoneme distinction and accuracy for both L1 Mandarin and English monolingual speakers. This was found to be more evident in phonemes like /v/, /ð/, and /ɪ/. For phonemes such as /w/, /s/, and /d/, restricting lexical choices sometimes led to decreased accuracy as in the case of English monolinguals. This may indicate that while lexical priming can help when distinguishing certain phonemes, it may also add confusion depending on the listener’s familiarity with the sounds. Our data reveals that L1 Mandarin speakers regularly outperform L1 English speakers when it comes to identifying difficult phonemes. This may suggest that being bilingual offers increased benefits when comprehending accented speech. This could be the result of bilinguals’ exposure to a variety of phonological systems, thus improving their ability to notice different variations in speech. On the other hand, however, L1 English speakers performed slightly better than bilinguals when identifying phonemes such as /s/, /d/, and /iː/ found in “beat”, likely due to their knowledge of native English phonological patterns. Both the L1 English monolinguals and the L2 bilingual Mandarin speakers presented a visible loss of distinction between certain vowel sounds. We found that participants would treat the phonemes /ɛ/ and /æ/ as interchangeable. This highlights the allophonic behavior observed in these two sounds.

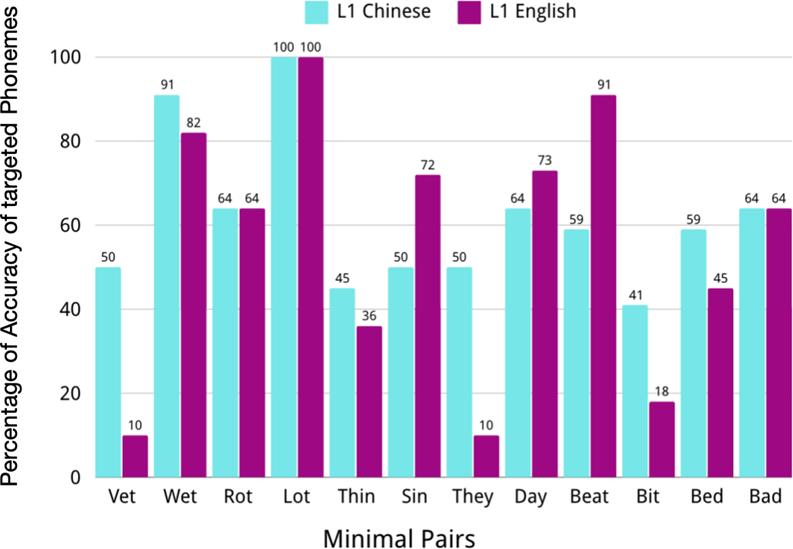

Figure 1. Accuracy of participants identifying targeted phonemes

Based on the graph, L1 Chinese speakers may demonstrate greater proficiency in identifying the phonemes /v/ in “vet” (L1 Chinese 50%, L1 English 10%), /w/ in “wet”, /θ/ in “thin”, /ð/ in “they”, /ɪ/ in “bit”, and /ɛ/ in “bed.” For the phonemes /r/ in “rot”, /l/ in “lot”, and /æ/ in “bad”, both L1 Chinese and L1 English speakers might exhibit similar levels of accuracy. However, L1 English speakers may perform slightly better in identifying the phonemes /s/ in “sin”, /d/ in “day”, and /iː/ in “beat”.

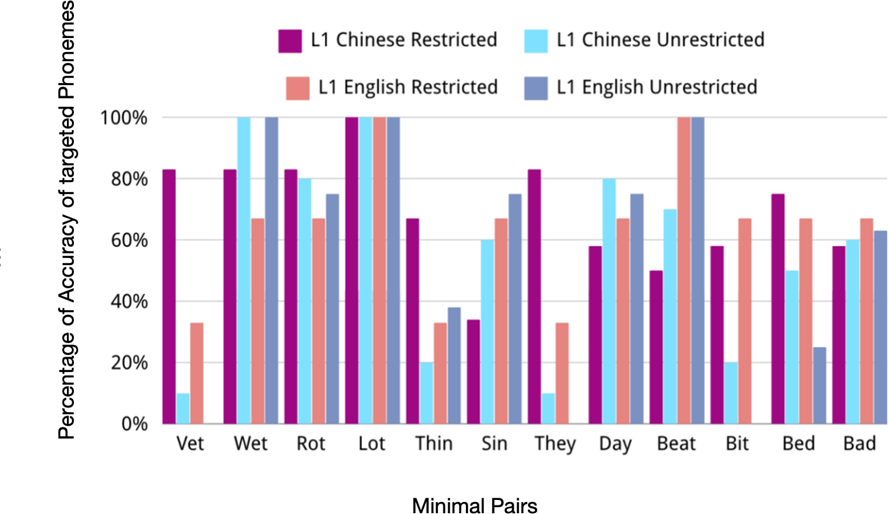

Figure 2. Accuracy of participants identifying phonemes in unrestricted and restricted lexical selections

The graph illustrates that the introduction of lexical priming significantly enhances the accuracy of identifying the phonemes /v/ in “vet”, /ð/ in “they”, /ɪ/ in “bit”, and /ɛ/ in “bed” for both L1 Chinese and L1 English speakers. Conversely, restricting the lexical selections appears to result in decreased accuracy for the phonemes /w/ in “wet”, /s/ in “sin”, and /d/ in “day.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The data demonstrates that L1 Chinese speakers generally showed a greater ability to identify phonemes in several categories than L1 English speakers, supporting our hypothesis that bilingualism offers an advantage in understanding accented speech. For phonemes such as /v/ as in “vet”, /ð/ as in “they”, /ɪ/ as in “bit”, and /ɛ/ as in “bed”, L1 Chinese speakers performed significantly better, particularly when lexical priming was introduced. This suggests that their exposure to both English and Chinese phonological systems enhances their adaptability to variations in speech, including Mandarin-accented English.

In contrast, L1 English speakers showed slightly better performance in identifying phonemes such as /s/ as in “sin”, /d/ as in “day”, and /iː/ as in “beat”. These results may reflect their familiarity with native English phonetic norms and reliance on monolingual processing strategies. Interestingly, lexical priming decreased the accuracy for certain phonemes, such as /w/ as in “wet”, /s/, and /d/, indicating that contextual cues might sometimes interfere with phoneme recognition.

These findings highlight the cognitive flexibility of bilinguals in adapting to unfamiliar phonological patterns, supporting the idea that bilingualism provides a distinct advantage in processing accented speech. The results also suggest that bilingual individuals utilize broader phonological frameworks, allowing them to overcome challenges posed by non-native accents more effectively than monolinguals.

While the hypothesis is largely supported, the findings indicate that the advantage of bilingualism is not universal across all phonemes. The performance gap between L1 Chinese and L1 English speakers was more pronounced for certain sounds, suggesting that the extent of bilingual advantage may depend on the specific phonological features being tested. Future research could explore the impact of accent exposure or phonological awareness training on phoneme recognition in accented speech. Additionally, investigating a wider range of accented speakers and phonemic contrasts could provide more comprehensive insights into the adaptability of bilingual and monolingual listeners. These findings could inform the development of teaching methodologies that leverage bilingualism to improve communication in multilingual and multicultural environments.

Furthermore, TED Talk “The Benefits of a Bilingual Brain” presented by Mia Nacamulli, demonstrates the cognitive benefits of bilingualism. This talk explores the neurological benefits of language bilingualism, such as its cognitive flexibility, mental agility, and even perceptual gifting (Nacamulli, 2015). Though the talk is a comprehensive account of how the bilingual brain functions, it raises questions about how these cognitive benefits could transfer to real-world language abilities, like being able to comprehend different accents and navigate confusing linguistic landscapes. Researchers are still exploring how bilingualism could yield tactical benefits in processing and understanding languages.

In conclusion, we set out to explore whether being bilingual provides an advantage in understanding accented English. By using minimal pairs and testing L1 Mandarin and L1 English speakers, we discovered that bilingual participants demonstrated greater accuracy in identifying challenging phonemes, especially those not present in Mandarin. Our research revealed that bilingualism offers a unique cognitive flexibility in processing linguistic variations. While the advantage was not consistent across all sounds, we found compelling evidence that exposure to multiple language systems enhances speech comprehension. These insights not only contribute to linguistic research but also suggest potential implications for developing more effective communication strategies in multilingual environments.

References

Bsharat-Maalouf, D., Degani, T., & Karawani, H. (2023). The involvement of listening effort in explaining bilingual listening under adverse listening conditions. Trends in Hearing, 27, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165231205107

Li, F. (2016). Contrastive Study between Pronunciation Chinese L1 and English L2 from the Perspective of Interference Based on Observations in Genuine Teaching Contexts. English Language Teaching, 9(10), 90. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n10p90

Li, M., Cheng, L., & Kirby, J. R. (2012). Phonological awareness and listening comprehension among Chinese English-immersion students. International Education, 41(2), 46–65. Retrieved from https://trace.tennessee.edu/internationaleducation/vol41/iss2/4 Nacamulli, M. (2014). The benefits of a bilingual brain [Video]. TED Talks.

https://www.ted.com/talks/mia_nacamulli_the_benefits_of_a_bilingual_brain?subtitle=en Perfetti, C. A., Landi, N., & Oakhill, J. (2005). The acquisition of reading comprehension skill.

In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 227–247). Blackwell.

Roberts, Lacy (Host). (2022, May 31). When Accents Speak Louder than Words (No. 61) [Audio podcast episode]. In Undark. https://undark.org/2022/05/31/podcast-61-accent-bias-sciences/

Vandergrift, L. (2007). Recent developments in second and foreign language listening comprehension research. Language Teaching, 40(3), 191-210. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004338