Viktoria Hovhannisyan, Alisara Koomthong, Tomoe Murata, Kota Tsukamoto

Syntactic knowledge is the understanding of the connection between the words in a sentence. This skill develops over time in children when being exposed to a language from their environment. Previous research demonstrated that bilinguals show different structured outcomes for language and cognitive performance, in terms of being at disadvantage. This study argues that bilinguals with English as a second language speakers who grew up acquiring English tend to develop syntactic awareness more effectively and, as a result, perform better on grammatical tasks as opposed to native English speakers. We collected data from 20 undergraduate students and asked them to complete grammar tasks along with answering questions that would reveal the level of their syntactic knowledge. We found that native English speakers are more knowledgeable in syntactic structures based on their scores than international bilingual English speakers.

Intro & Background:

This study is designed to test two populations, native English speakers and non-native English speakers in the adult population. The research is aiming to observe metalingual awareness, more specifically syntactic awareness in adult monolingual and bilingual populations. To narrow down our focus of the study, we will not be assessing any other aspects of language, such as phonological awareness, vocabulary size, or accent.

Over the years, various studies have suggested that bilingual speakers have disadvantages in language and cognitive performance. For example, one study has demonstrated that bilingual children develop vocabulary more gradually in each language and perform poorly on language proficiency tasks than monolingual speakers of the same language (Bialystok and Feng, 2011 & Oller and Eilers, 2002). Additionally, another study has shown that adult bilinguals have limited vocabulary size (Portocarrero, Burright, & Donovick, 2007). They also produce fewer words in verbal fluency tasks (Rapp, 2005). This topic has been very well researched, and the results of several studies have actually shown that there is a disadvantage to bilingualism.

However, the study that was conducted on the children population found that bilingual children sometimes perform better than their monolingual peers on grammaticality judgment task which is a form of assessing metalinguistic awareness (Foursha-Stevenson & Nicoladis, 2011). They argue that some of these differences can be accredited to the fact that bilinguals have to learn to control attention to language choice. Based on the results where the children undergo those differences, we believe that the same concept applies to the adult bilingual population. Furthermore, a study that tested the effects of monolingualism-bilingualism on a foreign language learning using a grammatical judgment task showed that bilinguals performed significantly better than monolinguals after adolescence, although there was no difference in performance before adolescence (Yeganeh 2013). The author also points out that being bilingual is effective for foreign language acquisition after adolescence and they achieve higher results in the learning process. In short, two different studies suggest that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals on grammaticality judgment tasks during childhood and after adolescence. Moreover, we believe that native English speakers do not typically spend as much time learning grammar rules as the bilingual population, since they acquire language naturally (i.e., family, friends, schools, home, community). Whereas the non-native speakers who grew up in a foreign language environment generally square language in the school setting where they get formal lessons on topics such as syntactic rules. Considering this difference in both populations in addition to the bilingual advantage in grammar judgment tasks, we predict that non-native English speakers would perform better on grammatical assessment than native English speakers.

Methods:

To test our hypothesis, we collected 20 responses from undergraduate college students, 8 male and 11 female and 1 other, who are either native monolingual English speakers or bilingual English speakers. We assumed that the ideal bilingual candidate should have learned English at around elementary school or after. As for an ideal native English speaker, they should not have been exposed to any second language input from the time of birth to about 7 years old. This reasoning was based on the critical period hypothesis, which argues that there is an ideal time window to acquire language in a linguistically rich environment and after that period it is much harder to acquire language (Bailey, Bruer, Symons, & Lichtman, 2001).

The study consists of two parts which was aimed to generate data about an individual’s English language skills and beliefs. The first part of the survey asked a series of bibliographical questions relating to their personal background and their history with language acquisition. Some of the questions were the following: “Is your first language English?”, “Do you speak a language other than English natively?”, “At what age were you first exposed to the English language?” etc. The second part of the survey asked all participants to take the “Michigan ECPE” grammar test which consisted of about 10-15 sentences that were designed to test an individual’s English grammar level. We used the highest level of the test since we were testing both native and non-natives college students who most likely already reached proficiency in the English language. Here is one of the examples of the grammar assessment.

To test the metalinguistic awareness of grammar of the individuals, we will modify the “Michigan ECPE ” grammar test and add a section after each sentence where participants will be asked to explain as to why they believe the answer they chose is grammatically correct. To analyze and evaluate the feedback of an open-ended response, we will categorize the response based on some key components of the response. First, we will be looking for key terminology used in the response. If the participant explains their answer giving the exact grammatical rule they applied, we would count that the participant has meta-knowledge about the syntactic rules and we will assign full credit for their response. When the participant does not define their answer using terminology but explains the gist of the rule then a full credit would be given for their response. If the participant does not use terminology nor explain the rule’s gist but rather gives a logical answer that explains their reasoning, we would assign a half-credit for their answer. Lastly if the participants give a very generic explanation such as “it sounds just right” or “I feel like it matches with the sentence” then we would not assign any credit to their explanation since it is lacking the source of their meta-knowledge.

To test the link between participants’ confidence level and proficiency, we will ask the participants to rate their confidence level after each question. Additionally, at the end of the questionnaire we asked participants if they have ever received formal lessons on English grammar during the schooling years. This step is crucial to determine the exposure of language input through the development of the participants.

Results & Analysis:

Based on the results, there was not a definite or clear trend that can confirm or annul our hypothesis. Our first group of participants, native English speakers, the majority of them scored much higher and are more confident than our bilingual speakers with English as L2 participants, which goes against our hypothesis.

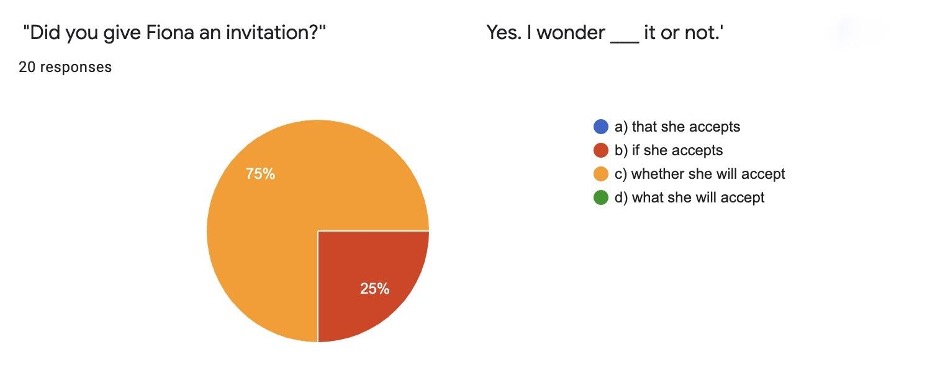

Figure 1 presents one of our questions that we’ve given to our participants. We believe that this question gives an accurate representation of our overall results. 75% of the participants scored correctly and within that percentile, 73% are native English speakers. The other 25% that answered incorrectly, most of them were internationals (80%). However, we also decided to look further into Question 10 where our participants struggled the most.

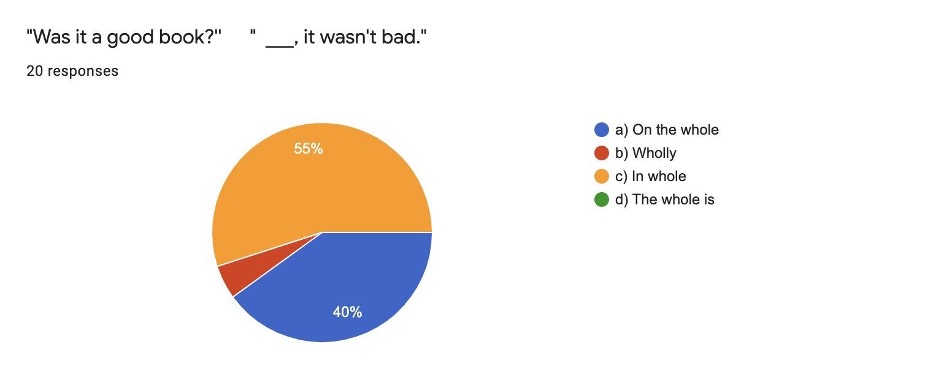

As shown in Figure 2, 60% of the participants chose “In whole” which was incorrect. Within that percentile, 33% were international bilingual speakers and 67% were native English speakers. This resulted in a large portion of the participants that answered incorrectly were native English speakers. As for the ones that answered correctly, 50% were bilinguals and 50% were native. From this, we concluded that the question might have been too complicated which gave us mixed results.

Even though most of the participants that scored highly were English speakers, there were some bilingual speakers that scored very highly. Looking at each participant, we noticed a pattern occurring in international bilinguals that did well: all were exposed to the English language at a young age.

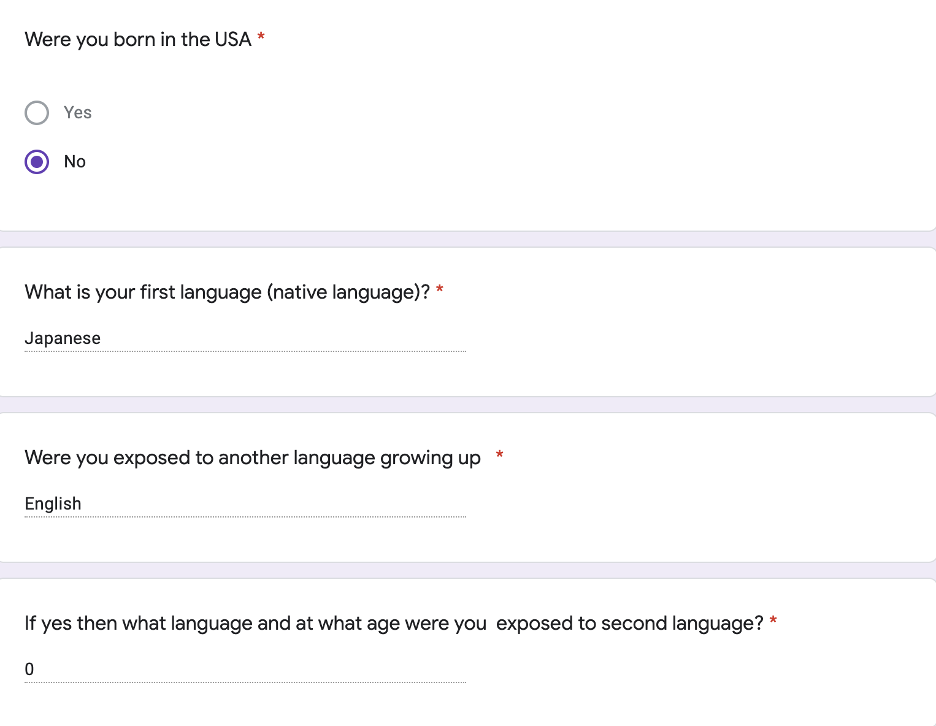

Figure 3 above is our ninth participant that scored 11/11. She was one of our two participants that got a perfect score with the other one being a native English speaker. As shown in Figure 3, she has been exposed to the English language at a very young age, even though she grew up in a foreign environment. Due to this observation, we analyzed the international bilingual speakers that did poorly on the assessment and noticed that they were not exposed to English until either in high school or college.

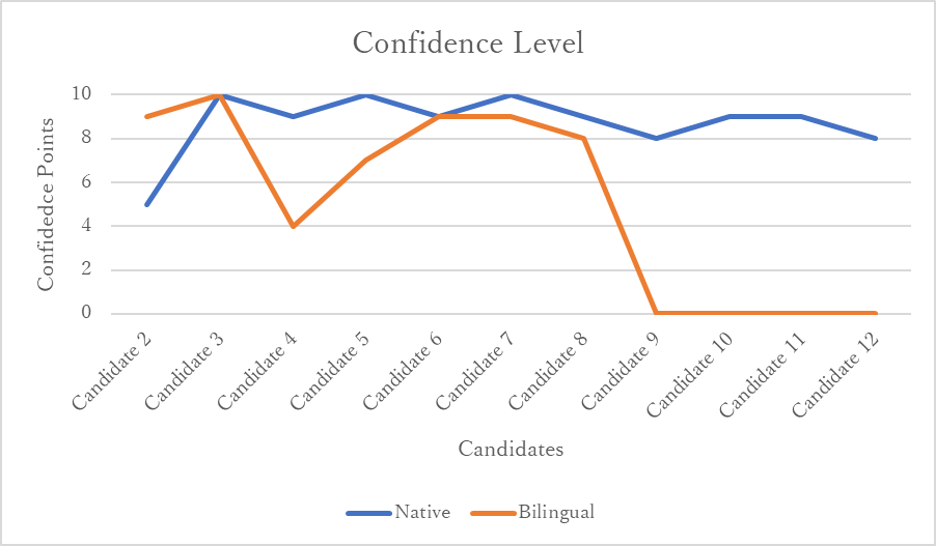

In terms of confidence level, most of the participants scored average or high after they finished the test. Only two participants scored low, ranging from 3 to 5 out of 10, on their confidence spectrum. Overall, native English speakers placed their confidence level higher than international bilingual speakers as shown in Figure 4 below.

Discussion & Conclusion:

Based on our findings, it did not align with our hypothesis. In page 3, “Methods” section, sentences from line 3 explains in detail that since we expected the international bilinguals with English as L2 to have more proficiency in syntactic knowledge, the result turned out to be quite the opposite. The points that we mentioned are probably the amount of time people have spent learning English. For the candidates, we only divided them into native English speakers and non-native English speakers. It could have been more detailed since international bilinguals do not always have proficiency in two languages. Additionally, we have not gathered their morphological knowledge, such as speaking and listening, so it is difficult to consider whether a candidate is proficient enough in the language. According to the article “Retaining an accent,” by Francois Grosjean, not every person growing up in the same country does have the same language level, and it will depend on their living environment (see paragraph 9 and 10 on Retaining an Accent). The project allowed us to gather a lot of information about them. Still, at the same time, we found a few points that we needed to adjust or add to proceed with a more detailed project.

For future reference, we believe this experiment is just the beginning of analyzing the bilingual’s and native speakers’ knowledge of English. To make the research more precise, we could separate the bilingual candidates in detail, such as bilinguals who grew up with English as their L1 and bilinguals who grew up with English as their L2. Both candidates have the categorization of bilinguals, but their level of proficiency will turn out different by their background in learning the language. It will indeed affect their knowledge when they are exposed to speaking English as their L1 and L2. Focusing on their ages will also make the project more solid. We gathered their ages but did not reference our analysis. Therefore, if we were to continue working on this project, we would want to focus more on the relationship between age and language. According to Inna Figotina, an educator, the age of a person starting to learn a language will affect their engagement with the language (listen after 21:00 on The Future is Bilingual). On the methodology, we could have set the questions more simply (see page 4, paragraph 3, “Methods”). We will change the difficulty of each quiz by putting Q1 as very easy and Q10 as most difficult. For our research, this method will allow us to figure out the English level, and we can create more analysis on each candidate group; native English speakers did not score perfectly but many got the difficult questions correctly, and many international bilingual candidates got high points but none of them got difficult questions correct. By changing these methods and the target participants, we could gather the information for a deeper analysis of the relationship between bilingualism and English.

In conclusion, research on bilingual speakers and native English speakers allowed us to recap the behavior and the attitude toward the language. Many of the previous experiments and the research supported our hypothesis. However, the result was not the one that we expected. We still believe in our hypothesis that native speakers will not take much effort into learning their own language (English) compared to non-native or international bilingual speakers. However, it can be interesting to figure out how learning will always relate to how they will master one language. Overall, the research brought us to a new idea of bilingualism and the behavior toward their language, and we will continue to focus on that point.

References:

Bailey, Bruer, Symons, & Lichtman (2001) in Bailey D.B., Bruer J.T., Symons F.J., Lichtman J.W. (Eds.). (2001). Critical thinking about critical periods. Baltimore: Paul Brookes.View Full Reference List)

Bialystok, E., & Feng, X. (2009). Language proficiency and executive control in proactive interference: evidence from monolingual and bilingual children and adults. Brain and language, 109(2-3), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2008.09.001

Cummin, J. (2004). D. Kimbrough Oller & Rebecca E. Eilers (eds), Language and literacy in bilingual children. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters, 2002. Pp. vii 310. Journal of Child Language, 31(2), 424-429. doi:10.1017/S0305000904226290

Foursha-Stevenson, C., & Nicoladis, E. (2011). Early emergence of syntactic awareness and cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children’s judgments. International Journal of Bilingualism, 15(4), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006911425818

Grosjean, François. (2013). Having an accent in a language. Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/life-bilingual/201301/retaining-accent

Portocarrero, J. S., Burright, R. G., & Donovick, P. J. (2007). Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of clinical neuropsychology : the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 22(3), 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.015

Rapp, B. (2015). Handbook of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal about the Human Mind. Psychology Press. Philadelphia 2001, pp. 321-345.

Google. (n.d.). The future is bilingual – 1 year as a published author – interview with inna. (2021) Google. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9hbmNob3IuZm0vcy8yNmVlZTNkNC9wb2RjYXN0L3Jzcw?sa=X&ved=0CAkQlvsGahcKEwjQ_s2E29r3AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAQ

Yeganeh, M. T. (2013). Age constraint on foreign language learning in monolingual versus bilingual learners. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 1794–1799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.255