Qianwei Tao, Yinlin Xie, Zhifei Lei, and Yifan Yin

What makes bilinguals switch between languages mid-sentence, seemingly effortlessly? This captivating phenomenon, called code-switching, reflects the adaptability of bilingual communication. In our study, we focused on Mandarin-English bilinguals to explore how mixed-language prompts and formality levels influence their linguistic choices. Through analyzing responses from 20 participants aged 18 to 25, we found an unexpected pattern: formal prompts, traditionally thought to discourage language mixing, elicited higher rates of code-switching compared to informal ones. This discovery challenges long-held assumptions and shows the nuanced relationship between language, social context, and communication. By exploring further the structured nature of formal prompts and their impact on bilingual expression, this study shows how bilinguals use code-switching as a tool for communication. These findings open a window into the interaction of language and context, offering new perspectives on how bilinguals navigate their communication.

Introduction and Background

Language functions as more than just a tool for communication; it mirrors our social and cognitive realities. For bilinguals, this reflection shows in the phenomenon of code-switching, specifically intra-sensational code-switching, the act of alternating between two languages within a single sentence. This dynamic process is influenced by numerous factors, including context and language dominance. Language dominance also determines how fluently individuals switch between languages, and this is defined as the relative proficiency or preference for one language over another (Deuchar, 2020). For example, research shows that bilinguals frequently code-switch into their dominant language in casual settings but adhere to monolingual norms in formal contexts (Muysken, 2000). This shows that code-switching is not only a linguistic skill but also a social strategy that allows bilinguals to adapt seamlessly to diverse social cues and contexts (Green, 1998). Regarding these ideas, our study addresses the main research question: How do mixed-language prompts and varying levels of formality influence code-switching behavior in Mandarin-English bilinguals?

Research has shown that the context of communication heavily influences code-switching behavior. Formal settings often promote monolingual language use, emphasizing precision and adherence to linguistic norms (Myers-Scotton, 1993). On the other hand, informal contexts allow greater flexibility, enabling bilinguals to switch languages more freely (Deuchar, 2020). However, existing studies have not sufficiently explored how bilinguals respond to formal prompts containing mixed-language elements (Deuchar, 2020). This gap in the literature leaves unanswered questions about the nuanced interplay between linguistic input and social contexts.

Mandarin-English bilinguals provide us with an especially intriguing population for examining this phenomenon in this study. These bilinguals frequently engage in code-switching due to its structural and cultural contrasts between Mandarin and English (Green & Wei, 2014). This study tests the hypothesis that informal prompts with mixed-language elements will elicit higher rates of code-switching compared to formal prompts. We predict that Mandarin-English bilinguals will demonstrate strategies for adapting their writing to fit in contextual demands, with their switching behavior shaped by the linguistic input they take. Though there is extensive existing research, gaps remain in understanding how linguistic input and contextual factors interact to shape bilingual communication. Existing studies have focused on informal contexts or monolingual prompts, leaving questions about formal settings and mixed-language input underexplored (Deuchar, 2020). Addressing these gaps provides an opportunity to deepen our understanding of bilingual communication as a nuanced and adaptive process. Code-switching is not merely a linguistic phenomenon but a sophisticated strategy for navigating complex communication landscapes. It highlights the adaptability of bilinguals in managing diverse linguistic and social demands, which offers valuable insights into the interplay of language, context, and culture.

Methods

This study examined how Mandarin-English bilinguals respond to linguistic prompts varying in level of code-switching and formality. We recruited 20 participants aged 18-25, all Mandarin-dominant bilinguals with English as their second language. Participants were selected based on their self-reported regular engagement in code-switching to ensure appropriate alignment with the experimental tasks. Participants completed linguistic tasks designed to analyze their code-switching behavior. The tasks involved responding to prompts that differed in two key aspects: language composition (monolingual prompts [CS-] versus mixed-language prompts [CS+]) and context (formal, semi-formal, and informal settings). These variables were chosen to explore how prompt design and contextual formality interact to influence code-switching patterns. This approach allowed us to observe intra-sentential code-switching, where participants alternated between Mandarin and English within a single sentence, one of the most cognitively demanding forms of code-switching (Green & Wei, 2014).

The data collection of the study focused on the frequency and type of code-switching, with responses categorized based on their linguistic composition and analyzed for patterns across different conditions. To describe intra-sentential code-switching, we utilized two categories other than Monolingual condition. One is multiple-word insertion, which involves inserting multiple words or phrases from one language into the grammatical structure of another language within a sentence (Muysken, 2000). We also incorporate the alternational code-switching that has more extensive switching within a single sentence, involving longer phrases or clauses (Dulm, 2007). This categorization allowed for a nuanced analysis of the participants’ code-switching behavior in response to the linguistic prompts. Participants are told that they can respond in any language they feel most natural to answer. The categorized prompt of the survey is indicated below:

Group 1: CS Level Condition

- Monolingual/Informal:

- What’s the most random thing that’s happened to you this week?

- Alternational Code-switching/Informal:

- ○最近你发现啥新地方超好吃的, like legit worth recommending?

- ○(What new places have you discovered recently that are super delicious?)

- Multiple-word Insertion/Informal:

- 你最近有没有吃到什么literally超赞的地方, like那种vibe很chill而且超好吃的?

- (Have you eaten at any literally amazing places recently, like places with a chill vibe and super delicious food?)

- 你最近有没有吃到什么literally超赞的地方, like那种vibe很chill而且超好吃的?

Group 2: Formality Level Condition

- Formal Prompt/Mixed-language (CS+):

- 请分享一个 significant challenge in your academic journey and how you overcame it.

- (Please share a significant challenge in your academic journey and how you overcame it.)

- 请分享一个 significant challenge in your academic journey and how you overcame it.

- Semi-Formal Prompt/Mixed-language (CS+):

- 跟我们说说你最喜欢的hobby, and how it fits into your daily life.

- (Please tell us your favorite hobby, and how it fits into your daily life.)

- 跟我们说说你最喜欢的hobby, and how it fits into your daily life.

- Informal Prompt/Mixed-language (CS+):

- 一个朋友发消息问你 “你周末打算干嘛? Any fun plans?” 你会怎么回答。

- (A friend texted you “What are you up to this weekend? Any fun plans? What would you reply? ”)

- 一个朋友发消息问你 “你周末打算干嘛? Any fun plans?” 你会怎么回答。

These categories align with the matrix language model and provide a clearer understanding of the extent of language mixing within a single sentence (Muysken, 2000; Dulm, 2007). Graphs summarizing the results were labeled with condition names, like “Figure 1 Code-Switching Frequency by Level of Code Switching” and “Figure 2: Code-Switching Frequency by Context Formality.” Also, graphs are titled as “Group 1: CS Level Condition”, and “Group 2: Formality Level Condition.” This ensured that findings were visually intuitive and accessible. We also framed our participant group as homogeneous in terms of their language dominance and bilingual proficiency to confirm group similarities. By aligning terminology with the matrix language model, we clarified “insertion” as the process of embedding words from one language into the grammatical structure of another (Muysken, 2000). Recruitment was conducted through social media platforms like Instagram and WeChat. A pre-survey assessed participants’ language dominance, proficiency, and code-switching habits. This survey included demographic questions and self-assessments of fluency and language usage patterns in formal and informal contexts. This streamlined methodology can effectively explore how linguistic prompts and context influence bilingual communication.

Results and Analysis

The experiment results are obtained from 20 participants, aged 18 years old to 25 years old. Male participants significantly dominate the sample, being 66.7%, while female participants take up to 33.3%. Most of the participants are currently enrolled in college or holding a bachelor’s degree. All participants share an advanced proficiency in their native language, Mandarin, and a moderate fluency in their second language, English. Based on the pre-survey scores, apparently there is a strong agreement among the participants that mixing languages is natural bilingual practice. They exhibit a tendency to mix languages more frequently in informal settings, such as being with family or friends. Meanwhile, they mix languages moderately in formal settings, usually for academic or professional purposes. They all show a high level of comfort using mixed language in online environments.

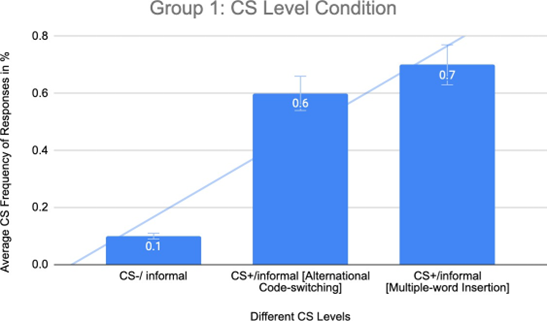

Survey 1 contains informal scenarios with three types of prompts: monolingual code-switching (CS-): e.g. “What’s the most random thing that’s happened to you this week?”; alternational code-switching (CS+) prompts: e.g. “最近你发现啥新地方超好吃的, like legit worth recommending? (What new places have you discovered recently that are super delicious?)”; multiple-word insertion prompts: e.g. “你最近有没有吃到什么literally超赞的地方, like那种 vibe很chill而且超好吃的? (Have you eaten at any literally amazing places recently, like places with a chill vibe and super delicious food?) ”. Results show that monolingual CS- prompts are the least likely to evoke code-switching responses (10%), and alternational CS+ ones are moderately likely to trigger code-switching (60%), yet multiple-word insertion ones are the most likely to prompt code-switching responses (70%).

In the graph below, the x-axis represents different levels of CS, while the y-axis represents the frequency of CS occurring in percentage. The overall graph shows a positive trend among the three types of prompts, indicating a correlation that the more insertions present within a sentence, the more likely it is for speakers to code-switch. These findings suggest that the structure and complexity of the prompt can be impactful to the frequency of code-switching. In informal contexts, prompts with more embedded English words facilitate code-switching more effectively.

Figure 1.Code-Switching Frequency by Level of Code Switching

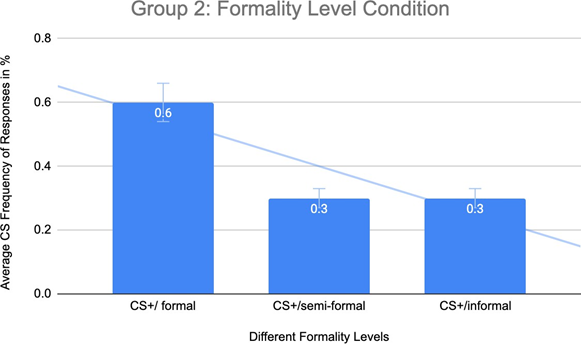

Survey 2 focuses solely on CS+ prompts across formal, semi-formal, and informal contexts. Unexpectedly, formal prompts elicit a higher frequency of code-switching (60%) compared to semi-formal (30%) and informal (30%) contexts. In the graph below, the x-axis represents different levels of formality, whereas the y-axis represents the frequency of CS occurring in percentage. The graph exhibits a negative trend overall, suggesting that the less formal the setting is, the less likely speakers would code-switch. This reversal of the initial formality hypothesis indicates baseline behaviors among participants. To exemplify, a formal prompt such as “请分享一个 significant challenge in your academic journey and how you overcame it.

(Please share a significant challenge in your academic journey and how you overcame it.)”, contains structured content and professional diction, thus encouraging interactive engagement and bilingual expression. Conversely, informal prompts like “最近你发现啥新地方超好吃的, like legit worth recommending? (What new places have you discovered recently that are super delicious?)” triggers monolingual Mandarin responses with rare occurrences of code-switching. This implies that participants will regard informal prompts as less demanding compared to formal counterparts, thus less likely to code-switch.

Figure 2. Code-Switching Frequency by Context Formality

The higher likelihood to code-switching in formal contexts contradicts the hypothesis that informality would raise the chances of language mixing. There are a few plausible explanations for this unconventional phenomenon.

- Baseline Behavior: participants interpret informality as less linguistically demanding than formality, meaning that they might use L1 exclusively, rather than spending more cognitive effort to insert L2 components into casual conversations.

- Prompt Design: formal prompts consist of naturally embedded English components, increasing the likelihood of participants to incorporate English into their responses. It explains how code-switching behavior of participants heavily rely on the design of prompts.

- Perceived Social Norms: speakers tend to showcase their bilingual ability more frequently in formal settings because professionalism is commonly associated with an advanced bilingual proficiency. To align with this social perception, they are more likely to engage in code-switching to demonstrate their fluency and competence.

These findings offer valuable insights for the field of bilingualism and in particular, code-switching. However, further research is needed to examine how bilingual behaviors can be shaped by sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic factors, and whether these linguistic trends are consistent among bilinguals with varying degrees of proficiency, or with different language combinations.

Discussion and Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides a deeper version of the relationship between contexts in bilingual communication based on previous research on code-switching in bilingual speakers, focusing on the code-switching behavior of Mandarin-English bilinguals. Surprisingly, the findings differ from traditional assumptions and the formal hypotheses: code-switching is more likely to occur for bilinguals when combined with mixed-language prompts (CS+) in formal contexts than in informal contexts. This untraditional result challenges the long-held view that the cognitive demands of processing mixed-language input and the structure and guidance in formal contexts actually encourage bilinguals to use code-switching strategically for expression and communication.

This encouragement would lead bilinguals to utilize code-switching as a tool for conscious and strategic communication, which is consistent with the theory that bilinguals adapt their language to specific contexts, and that prompts give specific language expressive demands to motivate bilinguals to higher attentional control to help them integrate the two languages for complex articulations. In addition, the structure and complexity of the prompts can be overwhelmingly significant in affecting the frequency of code-switching behaviors. Mixed-language prompts (CS+) consistently lead to code-switching expressions, which is consistent with Deuchar’s (2020) token modeling theory that prompts can motivate bilinguals to activate both languages simultaneously to communicate, making code-switching a natural and effective way of communicating, which proves the theory that code-switching is not a spontaneous or arbitrary process but rather a deliberate linguistic strategy used to carry out a specific conversational goal.

Although the study presents different challenges, certain limitations exist. The specific participant demographics and small sample size limit the results of the study to a great extent. Specific language choices are also a limitation, and different language choices in the same study could have led to variations in results. In the future, the choice of greater linguistic diversity, an unspecified participant population, and a larger sample size are key factors for obtaining further validation and more comprehensive experimental results. However, other factors, such as cultural diversity, language ability and individual differences, may also influence the results, which will require future researchers to make more careful choices about the conditions of their experiments.

Two Relevant Talk/Podcast

- TED Talk: “Code-Switching to Navigate the World Around Us” by Jaellin King

King (2019) explores how different languages can positively impact how people navigate their surroundings. She mainly discusses the importance of being fluent in more than one standard of language to communicate effectively within diverse communities in this TED Talk. This idea aligns with our study’s focus on how bilinguals respond to linguistic prompts in various contexts, particularly the formal, semi-formal, and informal settings examined in the research. King’s idea also aligns with Muyskens’ article, supporting that the patterns and frequency of code switching can be influenced by different context and cues (Muysken, 2000).

- Podcast: “Code-switching as a School Strategy” by IDRA

This podcast episode delves into how code-switching can be used in educational settings to

create more inclusive environments for students. It discusses building an inclusive curriculum and how to use code-switching to better support students. This is related to Green’s article that Code-switching is used by bilinguals as a social strategy that allows them to navigate in different contexts (Green, 1998).

References

Deuchar, M. (2020). Code-switching in linguistics: A position paper. Languages, 5(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5020022

Dulm, O. V. (2007). The grammar of English-Afrikaans code switching: A feature checking account. LOT.

GREEN, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism (Cambridge, England), 1(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728998000133

Green, D. W., & Wei, L. (2014). A control process model of code-switching. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 29(4), 499-511.

Green, D. W., & Wei, L. (2014). A control process model of code-switching. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 29(4), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2014.882515

IDRA. (2019, July 1). Code-switching as a school strategy – Podcast episode 192. https://www.idra.org/resource-center/code-switching-as-a-school-strategy-podcast-episod e-192/

King, J. (2019, November). Code-switching to navigate the world around us [Video]. TEDx Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/jaellin_king_code_switching_to_navigate_the_world_around_ us

Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual speech: A typology of code-mixing. Cambridge University Press. Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Social motivations for codeswitching : evidence from Africa / Carol

Myers-Scotton. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Yow, W. Q., Tan, J. S. H., & Flynn, S. (2018). Code-switching as a marker of linguistic competence in bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(5), 1075-1090. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918000078