Ella Bogen, Celine Cabrera, Emily Henschel, Alexis Robles, Holly Weston

Ever walked past a group of frat guys and heard them say things like “ferda” or “that’s fire”? You might think it’s all just casual talk, but our research shows there’s something deeper going on. We studied how fraternity men use slang and nonverbal cues to build bonds, shape identity, and signal group belonging at UCLA. Language in Greek life is important, not just to sound cool, but to distinguish yourself as an “in-group” member, rather than an “out-group” member. Basically: you’re one of them.

Our project combined interviews, surveys, and real-world observations of frat interactions across several UCLA chapters. We wanted to know: does using more slang actually make you feel closer to your brothers? Our findings show that slang works like social glue, marking who’s “in” and who’s not, reinforcing group norms, and helping brothers navigate power dynamics within the house. Frat guys might not seem like linguists, but they’re constantly doing sophisticated things with language, whether they realize it or not. In fraternities, words like “bet,” “dub,” or even made-up phrases circulate through the house quickly. But this isn’t just meaningless banter. These words carry social weight. We see slang everywhere, but fraternities offer a unique take. They’re structured, male-dominated social groups where “brotherhood” is taken seriously, and shared language reinforces that sense of closeness. So we asked: Does using more slang actually make frat guys feel closer to one another?

Introduction and Background

Linguist Asif Agha (2015) says that slang exists in “microspaces”, which are defined as tight-knit communities where language choices reflect shared practices. Fraternities are a perfect example of this. Frat slang isn’t just just casual, they’re performances of masculinity and markers of group status. According to Asif Agha (2015), “Many kinds of slang coexist with each other within a language community and define many micro spaces of interaction linked to specific social practices and groups.” Fraternity members’ interactions are the types of microspaces that slang is prevalent within, which is why we chose them for our study, mainly focusing on the significance and role of slang in each interaction.

According to Yanchun Zhou and Yanhong Fan (2013), “If somebody uses the words and expressions within a certain social group or professional group, he will blend with the group members from mentality. That is to say, if a student says a sentence containing the special college slang, he must want to get the result of showing and strengthening the emotion that he is belonging to the inside of the teenager group.” This aspect of assimilation into a group through slang will be a core focus of our study. The idea of an “in-group” and “out-group” regarding understanding and employing slang is elemental to our theory on how slang functions to build social identity and reinforce group norms among fraternity men.

The idea of being in and out of “the know” is highlighted by the following excerpt: “In general terms, identity is realized when those people who are competent with a slang word come to infer that a speaker who uses is a member of the group for whom use is conventional based on their knowledge” (Alice Damirjian, 2024). A study done by Scott Kiesling shows that specific linguistic choices within groups like fraternities, such as slang, serve as markers of group identity and solidarity among fraternity members. He analyzes the “-in” variant among fraternity members and (e.g, “walkin” instead of “walking”). Kiesling notes, “The -in form, through its widespread indexicality of casualness… is one of the resources Speed, Waterson, and Mick use to take these stances, along with other linguistic features.”(Scott Kiesling, 2005). This demonstrates how fraternities use specific linguistic forms to reinforce group cohesion through shared language.

In terms of linguistic properties typically found in the communicative patterns of slang among fraternity men, brothers often adopt distinct linguistic features that reinforce their group identity by differentiating insiders from outsiders. From an academic article by Pongsapan (2022), it is stated, “In the document analysis and questionnaire result, the researcher found that the students used language variations, especially slang in their interaction with various types, such as fresh and creative, compounding, imitative, acronym, and clipping.” Fraternity slang is reflective of this nature as most slang used by members is often a more casual and playfully coded language than standard, and often specific to Greek life. Phrases and expressions often reflect shared experiences, humor, or references that may be unintelligible to those outside the fraternity. The use of slang fosters familiarity and signals belonging.

Methods

We used a mixed-methods approach to capture how slang operates in these houses:

– Interviews: We sat down with UCLA frat members and asked them how their speech had changed since joining.

– Surveys: We gave participants Likert-scale questions and open-ended prompts.

– Naturalistic Observation: We attended casual hangouts to document body language and informal conversations.

Firstly we conducted a survey via Google Forms and collected 33 responses from Fraternity members in three different houses at UCLA. The survey included both closed and open-ended questions asking about their language use, perceptions of communication differences, and feelings of closeness with their brothers. Many of our questions were open-ended, so we conducted 3-5 minute one-on-one interviews with fraternity members for further data collection. We went deeper with interviews asking members how their language had changed overtime, how slang or jokes functioned in their house, and how these factors impacted their sense of identity and connection. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods helped us capture a fuller picture of fraternity communication. The survey gave us broader patterns, while interviews revealed personal experiences, shared rituals, and the emotional meanings behind the slang. Altogether, these tools are what allowed us to analyze not just what was said, but how language operates in fraternity settings to reinforce bonds, in-group norms, and a unique culture.

Results and Analysis

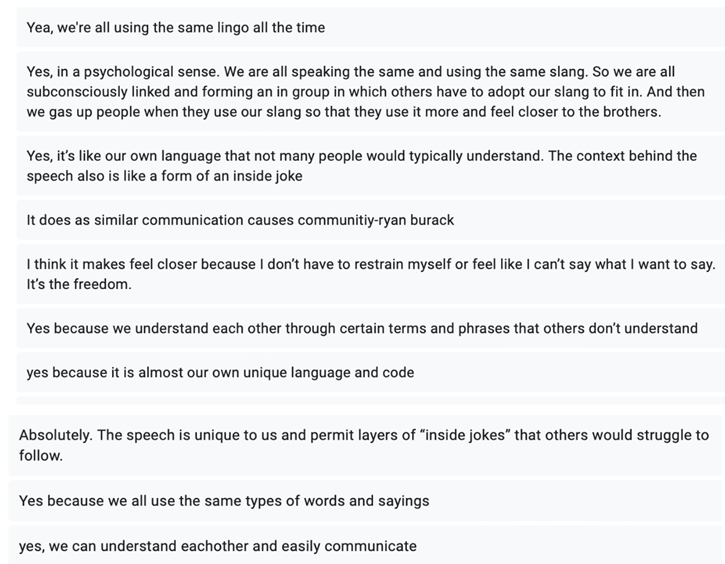

Figure 1: Answers to the question “Do you think the type of speech you use in the fraternity house makes you feel closer to your brothers? If so, why and how?”

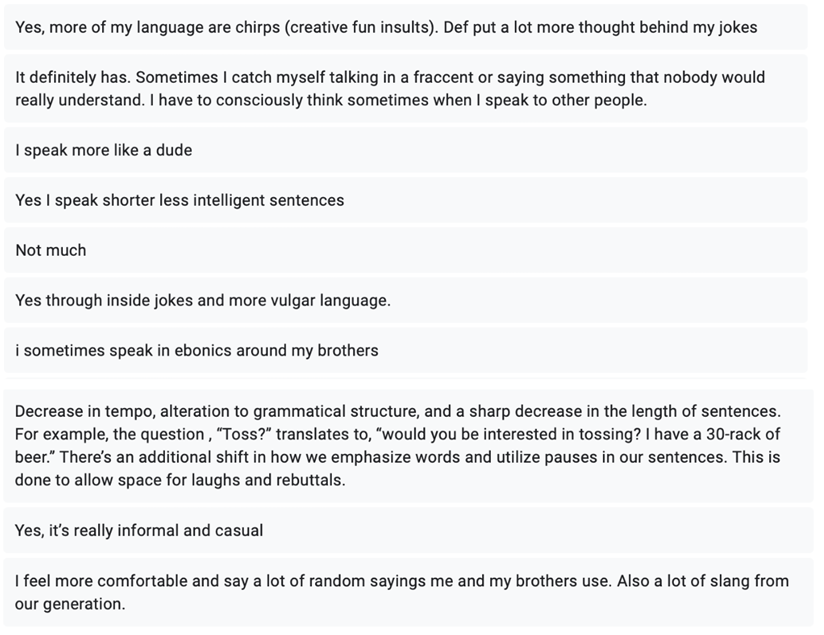

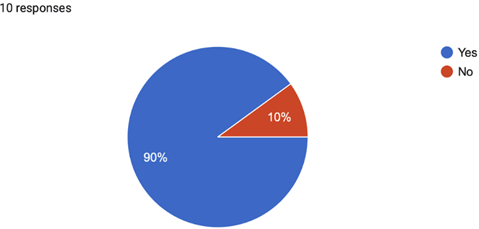

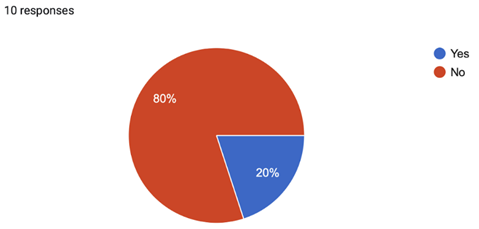

As seen in Figure 1, 100% of respondents agreed that the type of speech they used in the fraternity house made them feel closer to their brothers. Our survey also revealed that a majority of respondents felt their communication style had significantly changed since joining the fraternity (Figure 2). 90% agreed that they use house-specific slang specifically when within the frat (Figure 3). Interestingly, many also acknowledged that this language created an unintentional barrier to outsiders, and 80% of respondents believed that the average person would not understand the language inside the frat (Figure 4). This data highlights how slang functions not just as decoration, but as a central tool in building and navigating social dynamics within Greek life.

Figure 2: Has your language changed and adapted since joining a fraternity? If so, how?

Figure 3: In the house, do you think you speak differently?

Figure 4: Do you think the average person would understand slang said in the fraternity house among brothers?

Discussion and Conclusion

What the Brothers Said

One brother explained, “Yes, it’s difficult to describe, but there’s a lot of inside jokes, I would say, very, the least formal way that English can possibly be spoken” This sentiment came up often, that slang and inside jokes helped them feel more exclusively connected. Another said, “Um, Absolutely, but it’s difficult to describe. I would say it just comes down like limited vocabulary. For example, if we want to play a drinking game, we’ll just say just one word. Or going out, just go out. Sometimes, like, you get so close to each other, you could literally just point and it works. Kind of like, read each other’s minds.”

Another interviewee emphasized that their slang is constantly evolving: “ Like one person will say something funny and then it’s just kind of part of my lingo for at least like a month or two, and then before I know it, it’ll be something else.” This dynamic adaptation of language shows how slang reflects not only identity but also the constantly shifting social fabric of fraternity life, and the constant lexical changes we go through as a fast-paced generation.

The fraternity context also makes room for a specific kind of humor. “Like, I wouldn’t go insulting my classmates that I’m working on a group project [with], but, like, someone that I live with and, like, I’ve been through the thick of it with them, like, I feel all right, insulting them every once in a while. Totally.” This idea of bonding through teasing or “chirping” was repeated across multiple interviews. It illustrates that fraternity slang isn’t just about phrases; it’s about the tone, style, and culture of communication that define these relationships.

Future Directions

Our project opens up opportunities for questions and future research. Could intentionally modifying group slang affect bonding outcomes in new member orientations? Might there be a way to track how slang evolves in digital spaces like on GroupMe or Instagram DMs? As Greek life continues to adapt to changing campus climates and public perception, understanding the linguistic pulse of these communities may offer insights into broader shifts in masculinity, identity, and group belonging in Gen Z culture.

Our results were technically inconclusive, but heavily suggest a positive correlation between slang use and closer bonding. Slang in fraternities is a tool for navigating identity, forming friendships, and establishing social hierarchies. Our study shows that when frat brothers speak their own lingo, they’re doing more than talking. They’re building brotherhood, one “dub,” “ferda,” and “foenem” at a time.

References

Agha, A. (2015). Tropes of slang. Signs and Society, 3(2), 306–330. https://doi.org/10.1086/683179

Damirjian, A. (2025). The social significance of slang. Mind & Language, 40(2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12530

Kiesling, S. F. (2005). Fraternity men: Variation and discourses of masculinity. In D. Santa Ana (Ed.), Tongue-tied: The lives of multilingual children in public education (pp. 105–121). Routledge. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316501721_Fraternity_Men_Variation_and_Discourses_of_Masculinity

Pongsapan, N. P. (2022). An analysis of slang language used in English students’ interaction. Jurnal Onoma: Pendidikan, Bahasa dan Sastra, 8(2), 917–924. https://e-journal.my.id/onoma

Zhou, Y., & Fan, Y. (2013). A sociolinguistic study of American slang. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(12), 2209–2213.