Asher Erkin, Christine Kim, Valerie Morales, Karoline Vera, Camilla Zorzi

Why are younger siblings more likely to be excused for their lack of native language proficiency — and in turn, older siblings expected to be fluent? Following this common perception of bilingual speakers, our group hypothesized that in second-generation, Spanish-speaking households, older siblings would be less likely to produce speech errors and instances of code-switching than their younger siblings when instructed to describe scenes from a popular animated movie, Shrek. By asking sibling pairs to take our survey, transcribing their speech productions, and analyzing their differences in speech patterns in the context of sibling order and other demographic details, we showed that there was no obvious correlation between sibling order and fluency. However, based on self-reported personal experiences that participants believed had influenced their native language production, we observed that there are many more sociolinguistic factors that come into play when determining speakers’ comfort levels switching between their L1 and L2 languages.

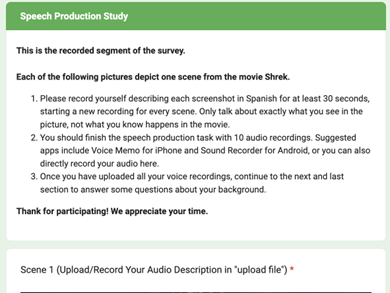

Introduction and Background While living in Los Angeles, the city with the largest Spanish-speaking population, we wanted to make use of this opportunity to explore the speech patterns that reside in second-generation, Spanish-speaking homes. Research indicates that older siblings often introduce English to their younger counterparts due to earlier and distinct sociolinguistic experiences (Obregon, 2011). Compared to parents, siblings tend to be more open to acquiring English and are more prone to a phenomenon called code-switching prevalent among bilinguals. Schools and jobs they go to provide more opportunities for English exposure, which then promotes bilingualism. In our study, all participants from second-generation, Spanish-speaking families expressed that Spanish is the main language used at home, whereas English is commonly spoken in public places, increasing the likelihood of code-switching. Previous studies reveal that older siblings commonly learn Spanish first at home, then later on learn English through school and friends, which helps them build a stronger Spanish foundation than their siblings due to their earlier exposure. Given that there is strong evidence that multilingual older siblings are often responsible for exposing their younger siblings to English (Obregon, 2011), we hypothesize that older siblings will have a stronger connection to their native language and will produce a more standard Spanish speech than their younger siblings. In this study, we wanted to analyze how sibling interactions in bilingual families impact language development, with key implications for approaches to learning and linguistic support in multilingual communities. Methods We recruited four groups of two or more bilingual siblings from second-generation, Spanish-speaking homes in Los Angeles, California. Each sibling filled out a survey with demographic background questions (age, primary language at home, gender, etc.) and an image-based storytelling exercise showing sequences from the film Shrek. They were given a collection of ten photographs and instructed to tell a story in Spanish. They were urged to record each narration separately so that the stories might be intricate and unique. 90 audio tracks, each lasting under 60 seconds, were generated as a result of this method. The recorded narratives were transcribed, and we examined the transcripts to look for instances of speech hesitations, code-switching, and self-corrections. Participants were found to be code-switching when they alternated between Spanish and English, and speech hesitations included grammatical, vocabulary, and pronunciation instances. To find linguistic trends in each sibling, we measured how frequently these instances occurred. To see how the language use of the older and younger siblings varied, we compared the results. We reasoned that older siblings would be more comfortable and proficient in Spanish, which would be demonstrated by fewer language switches and fewer errors. On the other hand, we expected the younger sibling to exhibit more frequent code-switching to English. Our goal in doing this type of study was to learn more about how multilingual siblings maintain their Spanish proficiency in a family setting and use their languages in diverse ways. Results and Analysis Analyzing the data and the recordings that we transcribed, we noted older siblings had descriptive language, using words and terms that not only described the scene but also described what the characters may be thinking or feeling based on the image. If the older siblings did not know how to describe some of the words, they would use circumlocution or find other ways to describe what gaps or errors they may have in their speech. For example, one of the older siblings described a rake as “que es una escoba, pero no es una escoba.” However, the attention to detail may have led to an issue among some of the recordings. Some of the participants showed a lot of hesitation, manifesting in fillers in their recordings. Some of the younger siblings showed more examples of code-switching and overall grammatical errors from the prescriptive grammar perspective. However, they were relatively strong and capable of showing a strong grasp of the language. However, there is no consistent language use among the older siblings and the younger siblings. The only similarity was the use of the filler words, where the siblings would say “uh” or “um,” which is the English use of the filler word, in comparison to the “eh” use of the Spanish filler word. This means that the siblings were most likely comfortable in English to rely on these filler words despite speaking in Spanish. Overall, the results of the study were inconclusive. It is clear that there was no common pattern among the older siblings and the younger siblings as described in our hypothesis. In reality, there was a scattered level of grasp in Spanish. Some of the younger sibling participants were better at speaking Spanish in comparison to the older siblings, and there were also older siblings who were more fluent in comparison to the younger siblings. This may have been due to the research design and the way participants were recruited for the experiment. There were even some speakers who stated in the self-reporting that they felt more comfortable speaking Spanglish, a language variety that combines English and Spanish. For example, one participant stated: “…I do speak more English to my siblings, while I do try to speak Spanish, but I do struggle… I speak a mixture of ‘Spanglish’ if anything.” This indicates that the sudden switch to just Spanish may be a difficult switch to trigger. We can analyze Spanglish as “setting the foundations for forming one’s identity, while simultaneously maintaining their culture” (Kaprielian, et al), or as the idea of code-switching and the idea of a language that is characterized by its switch between English and Spanish. This language use has a negative connotation due to its lack of being one language or the other. However, this notion is inherently harmful as it instead shows a unique language identity. One important point of information to target is the age of the participants, where the oldest participant is 32 years old and the youngest participant is 11 years old. This is an important angle to consider in regards to the analysis. Despite being from similar households, we cannot assume that the siblings emerged in similar language experiences. Thus, this presents a level of difficulty in grasping where each sibling resides in terms of language. This is a complex issue, and we cannot fully comprehend or gather what the upbringing was like for each child, as individual experience or time spent with parents may also demonstrate some understanding in the language differences. The age range of the younger children is another important factor, as the younger children may not be fully able to give a clear analysis given that this is something outside their age range, which is something that needs to be altered in further iterations of this study. Spanish-speaking identity is an important factor to consider when understanding why there are different levels of fluency among the Spanish speakers. As Spanish is becoming an increasingly common language in California (US Census), people’s relationship with the language is changing. Individual experiences will impact how one approaches the language, as some may feel more comfortable speaking Spanish in public. The identity of being a bilingual speaker of Spanish and English is changing, where the younger generation or the younger siblings may feel pride and adapt their Spanish speaking identity as something they are proud of in comparison to the older sibling, who may have previously rejected this identity of themselves when Spanish was a less commonly spoken language in California. It is difficult to reverse the images and associations that may have been created for the older sibling but instead may be implemented for a younger sibling whose language is beginning to develop. Their understanding of their relationship to language is different in comparison to the older sibling. However, this cannot remain consistent among all siblings and speakers of Spanish, and this will vary greatly through individual experience. Discussion and Conclusion We chose to analyze speech errors and instances of code switching to represent the level of fluency of each sibling pair because we primarily wanted to gauge the difference of these productions between the younger and older siblings. We had expected to find that there would be a clear increase in these behaviors for the youngest sibling, though that was not the case — the level of comfort each participant pair had with their native languages seemed to be more reliant on their self-reported levels of exposure than their sibling order. Though our study mainly sought to correlate sibling order with L1 language fluency and thus did not focus as much on objectively analyzing personal experiences and exposures, we believe that relying upon the participants to self report these aspects of their lives gives us enough of an idea of the bigger picture to determine that this was indeed a greater influence on their L1 language production than solely sibling level. Thus, we observed that for bilingual second generation Spanish speaking households, the level of comfort that a speaker has in switching between their L1 and L2 languages is impacted by many social and cultural experiences that cannot be analyzed with a simple sibling order heuristic. In the future, we would like to perform a more rigorous analysis of participants’ backgrounds — particularly during their early language development — by redesigning our experiment. Instead of requesting a description of 10 screencaps of a popular form of media, we would have asked them to describe a smaller number of their most vivid memories of L1 language usage and learning in early stages of development. While L1 fluency is undoubtedly impacted by individual life experiences that extend beyond this period, this method would allow us to specifically correlate the impact of formative linguistic experiences with their comfort switching between their L1 and L2 languages. Ultimately, our project idea sought to address one aspect of the stigma within bilingual communities against members who are not fluent in their L1 languages. While older siblings may be expected to be more fluent in their native language than younger siblings due to social expectations or assumptions, we concluded that fluency cannot be solely attributed to this factor. We also encourage readers to be mindful of the fact that the concept of cross-linguistic fluency exists within the rigid and colonial boundaries of natural language. The sociolinguistic factors that affect this trait are more opaque than they may seem, and fluency is simply a matter of being able to quickly categorize linguistic features between L1 and L2 on demand. We hope that this reframing of fluency and natural language shows that perceived markers such as sibling order should not be used to cast judgment upon speakers. References Census.gov. (n.d.). U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Los Angeles County, California. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/losangelescountycalifornia. Kaprielian, L., Santana, O., & Sadiq, S. (2024, May 27). Languaged Life. http://languagedlife.ucla.edu/bilingualism/code-switching-a-phenomenon-among-bilinguals-and-its-deeper-role-in-identity-formation/. Obregon, N. B. (2011). Older siblings teaching language skills and early literacy skills in their play with younger siblings / Nora Briselda Obregon. University of California, Los Angeles. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/older-siblings-teaching-language-skills-early/docview/879657630/se-2?accountid=14512. Shin, S. J. (2002). Birth Order and the Language Experience of Bilingual Children. TESOL Quarterly, 36(1), 103–113. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3588366. Tavits, M. & Pérez, E. O. (2019). Language influences mass opinion toward gender and LGBT equality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(34): 16781-16786. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31383757/.