Pauline Antonio-Nguyen, Elizabeth Gin, Anna James, Jennifer Padilla, Shanna Yu

An internet phenomenon: the Alpha Male. These men view the world in black-and-white gender roles steeped in misogyny, where women are not their equal and are expected to be subservient to them. This study takes the philosophies behind existing research done on conversation patterns between men and women and applies them to these alpha males. Do their beliefs and attitudes show up in how they speak? How do they navigate conversations compared to their non-alpha equivalents? While existing studies on aspects of speech like turn-taking and interruption have been largely inconclusive in the world of gender at large, we will be taking conversation analysis into the domain of alpha males in hopes of more conclusive results. What kind of language do they use to refer to those they find lesser, and do they interrupt women more than they do men? An alpha male’s word choices may reflect their misogynistic principles in potentially derogatory ways, and they may be more prone to interrupting others than a non-alpha male is.

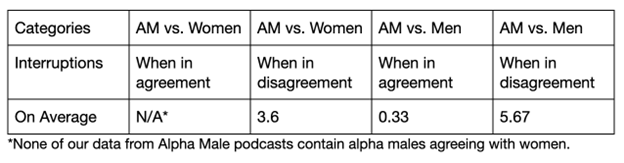

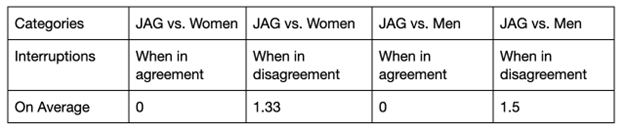

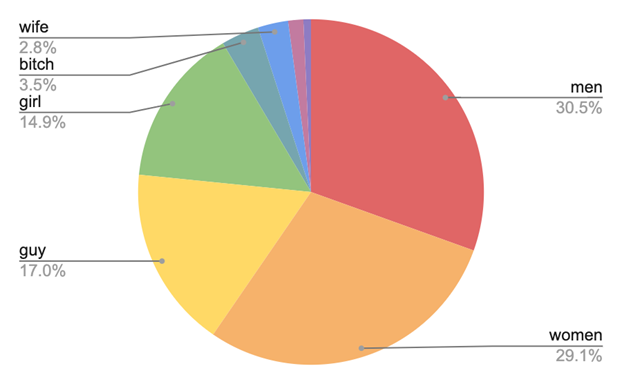

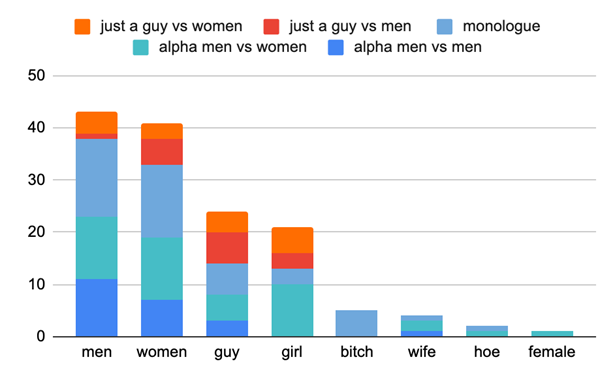

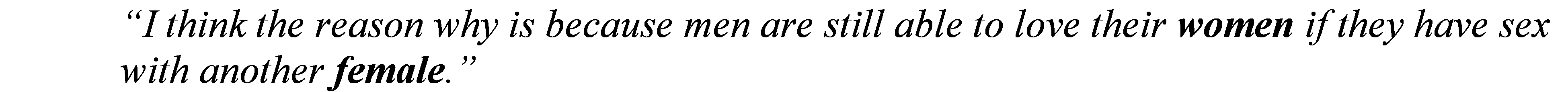

Introduction and Background The term “alpha male” has existed for many generations now. This term generally refers to a dominant individual, both within human social groups and animal behavior (Ludeman et. al, 2006). For further insight into exactly what an alpha male is, we recommend taking a look at this YouTube video discussing the “science” behind alpha males. The term has now evolved though, and in the internet sphere, it is generally accepted that “alpha males” are individuals who place heavy importance on being dominant, especially in terms of control over women. A good example is Andrew Tate, a self-proclaimed alpha male who took the internet by storm in 2023. We decided to look at two linguistic aspects: lexical items and conversational analysis — specifically interruption. An existing study on alpha males highlights their use of lexical pathways as a “means to further try to push their egotistical and misogynistic agenda” (Lawson, 2020). Additionally, in the eyes of an alpha male, women’s value is inherently tied to concepts like virginity and how subservient they are to the man who “owns” them. In terms of interruption, studies that cover whether men or women interrupt each other more have yielded mixed results, such as one where a “high-dominance predisposition,” a self-explanatory term established in-study, prompted men to interrupt more often than women with the same disposition (Rogers, 1975) versus another where others found that there was no significant difference between their test groups of men and women (Johnson & Aries, 1983). How exactly do alpha males interact with those around them, and does their behavior change based on which gender they speak with? Through our analysis, we look into the frequency of patterned and marked vocabulary and interruption as a way to enforce gender ideas and establish their place in a hierarchy. Methods Our main sources were TikTok and YouTube. We searched for videos using keywords — “alpha male podcasts,” “alpha male podcast women,” “alpha male podcast men,” etc. — to find videos. We compiled a total of 35 videos, mostly TikTok videos and some YouTube videos. The TikTok videos were used to give us our word frequency data, and both the TikTok videos and YouTube videos were used in our interruption data. We thought the shorter TikTok videos would be a decently accurate portrayal of what alpha males would deem as “important” or “worthy” enough to emphasize because these clips were moments that editors had purposely picked out of longer episodes. We then made transcripts from the TikTok videos and used the search function to find out how many times a certain word was said in a certain context. The four contexts were two alpha male contexts and two control contexts. We looked at when alpha male podcasters talked with other men and when they talked to women. For the control group, we looked at non-alpha male podcasters talking to other men and when they talked to women. As previously mentioned, we were also interested in the phenomenon of alpha males interrupting people in conversational settings. Therefore, we also kept track of the number of times that alpha males interrupted both the experimental and control groups. Results and Analysis Looking at the interruption data, we saw some interesting results. Overall, we found that both alpha male podcasters and non-alpha male podcasters were actually more likely to interrupt other men than interrupt women. When we look at the breakdown of whether or not the two parties were in agreement though, we found some interesting results. We found that rather than gender being the factor that affected the average number of interruptions, the more important factor was whether or not the podcasters were in agreement with the other person. We can see this particularly clearly in the data comparing alpha male podcasters talking to other men when they agree vs. when they disagree. It was a bit hard to draw a clear conclusion because we didn’t actually have any data of alpha male podcasters agreeing with women at all. Comparing this data to the non-alpha male podcasters though, alpha male podcasters overall interrupt whoever they are talking with a lot more than non-alpha male podcasters. Also, for non-alpha male podcasters, the difference in the average number of interruptions when talking to women vs. when talking to men was much smaller. Although we often see alpha males project their dominance over women, the projection of dominance over other men is often overlooked. In our data, we can see that projecting dominance over a man may be more important than projecting dominance over a woman. After all, an alpha male is only an alpha male if he is higher up on the hierarchy than other males. These results could also be the result of the women guests allowing the alpha male podcasters to talk for longer periods of time compared to men guests. If the women were speaking less, then there would be less opportunities for the alpha male podcaster to interrupt. Regarding the lexical data, contrary to what we initially predicted, we did not see a high use of derogatory language towards women. Pretty substantially, the majority of words used to reference men and women were the words “men” and “women.” However, when looking at a breakdown of what words are used in what context, there are more interesting results. As we can see, alpha male podcasters use more words to refer to women than non-alpha male podcasters. The non-alpha male podcasters used only the words “women” and “girl” and didn’t use any other references when talking about women. When talking to women, alpha male podcasters almost exclusively used the word “girl.” In our data, they never used the word “girl” when talking to other men. Similarly, alpha male podcasters only used the words “hoe” and “female” when they were talking to women. There was only one instance of an alpha male podcaster using the word “female,” and it was when he was talking to some women about cheating. The alpha male podcaster said: What is interesting about this is that he also used the word “women” in the same sentence. He made two categories of women, “women” and “females.” When talking about the partner who receives love from a man, he used the word “women.” When he was talking about a person that a man would have sex with, he used the word “female.” This creates a dichotomy between women who are loved — “women” — and women to have sex with — “females.” When we compiled the data, we counted both plural and singular forms for every word, and there was an overall trend of non-alpha male podcasters using singular forms, while alpha male podcasters often used the plural forms. Usually, when non-alpha male podcasters were talking about men and women, they would be talking about specific situations, while alpha male podcasters would usually be making sweeping statements about men and women in general. In general, there seemed to be an overarching pattern of alpha male podcasters talking about the general broad topic of “men and women.” On the other hand, we actually found it a little hard to find non-alpha male podcasters talking about men and women as a broad topic, and usually, they would be talking about their own personal experiences or hypothetical situations regarding romantic relationships. Also, non-alpha male podcasters on average seemed to be younger than the alpha male podcasters, which would explain the low frequency of the word “men” by non-alpha male podcasters. It seemed that they were more comfortable referring to themselves and other men as “guys.” Interestingly though, when comparing words referencing men and women, the words “men” and “guy” were more frequent than the words “women” and “girl.” There was only a slight difference, but it is interesting to see that it was consistent that words referring to men were used slightly more than their feminine counterparts. This could also be explained by the fact that both groups of podcasters are slightly more likely to make statements relating to themselves, as they identify as men. The most compelling data we found in the TikTok video transcripts were words that referenced men and women, and we didn’t find any other specific words that were super frequent in the videos we looked at. There was no quantitative data on other words, but overall, alpha male podcasters definitely expressed ideas of sexism and gender essentialism much more frequently than non-alpha male podcasters did. Discussion and Conclusions In our study, we wanted to investigate an “alpha male’s” general language and the prevalence of certain words they use. The results of our findings suggest that alpha males do try to impose and assert dominance and interrupt others when they are speaking to others. Alpha males showed intolerance when they were faced with conversations with males or females who did not agree with their point of view. We found a lot of interesting things in our data, things that matched up with what we originally predicted and things that did not. In our lexical item results, the frequent usage of “girl” about women by alpha male podcasters is extremely interesting. Because these men often criticize women and the behaviors they associate with women when doing so, the preference for the word “girl” when talking to women directly could be taken as a form of dismissiveness towards women and their autonomy, infantilizing them and writing them off as something that needs to be taught and controlled. In the interruption results, the assertion of dominance from alpha male podcasters escalated when there was a disagreement between alphas and other men in conversations. It seems that alpha males not only want to assert their dominance over women but also other men. Overall, these patterns that we witnessed in our research reflect underlying tactics of dismissiveness and clear tactics of dominance used by alpha males. Unlike what we thought, alpha males were more subtle in terms of low use of marked words; they instead used unmarked words, perhaps because they realized that derogatory terms are not as socially acceptable. On the other hand, something like interruption is not something that is clearly marked or visible, so alpha males seem to fully employ that tactic. Also, some things that are important to note is that it was pretty obvious that a lot of these alpha-male podcasters were trying to “rage bait” and get a reaction out of their guests or the audience. Most of the videos that popped up were alpha male podcasters berating women about their choices on men, speaking on how women should act, etc. Due to the nature of social media algorithms, it’s impossible to randomly pick videos. However, in a way, it does show which videos are getting viewed the most and, in turn, what the average person would be more likely to come across. Something else that we did not look at specifically was sentiment analysis. If we looked more closely at what sentiments were expressed when using “girl” vs. “women,” for example, or between alpha male podcasters and non-alpha male podcasters, we might have seen more data that lined up with our original predictions. Even if alpha male podcasters did not use derogatory terms for women, they still expressed negative sentiments about women. Alpha males are often seen as a meme or outrageous, and even though the statements they say often are, it seems that there is some kind of conscious effort to stray away from derogatory terms that would immediately be flagged by the general public. Through our analysis, we can see that there are many other factors and tactics that seem to be a part of the repertoire of alpha males. We have only looked at the surface, but hopefully, our research could serve as a starting point for investigating other factors that go into the way alpha males speak. References Johnson, F. L., & Aries, E. J. (1983). Conversational patterns among same-sex pairs of late-adolescent close friends. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 142(2), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1983.10533514. Lawson, R. (2020, January 14). Language and masculinities: History, development, and future. Annual Review of Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011650. Ludeman, K., & Erlandson, E. (2006). Alpha Male Syndrome. Harvard Business Press. Russell, E.L. (2021). Masculinities, Language, and the Alpha Male. In: Alpha Masculinity. Palgrave Studies in Language, Gender and Sexuality. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70470-4_2. Roger, Derek B., Bull, Peter E., & Smith, Sally (1998). Journal of Language and Social Psychology. The development of a comprehensive system for classifying interruptions. 7:27-34.