Max Orroth, Arielle Gordon, Jillian Litke

We’ve all heard of the acronym lol, short for “laugh out loud”, and have used it in more than one context. Lol differs from other internet-born acronyms, like ROTFL, as it has become widespread across social platforms all over the world and has maintained a role in American English vernacular to this day. Some use it to “soften the blow” of a harsh statement. For others, it is tacked onto the end of a sentence to convey sarcasm or passive-aggressiveness, but does that mean its meaning has changed over time? Our study analyzed a series of tweets from Twitter to determine if the use of lol has increased in passive-aggressive contexts from 2008-2022. We also categorized where lol appeared in the tweet, such as the beginning of it, the middle, or the end to help determine the true meaning or intent of the tweet.

Introduction

How does the three-letter acronym lol manage to make its way into so many of our online conversations, even those that aren’t inherently funny? Lol is one of the first internet terms to become popularized and has been in use for a while, thus the acronym finds itself in a myriad of situations, each with an abundance of meanings, making it somewhat of a linguistic chameleon. Is lol being used more commonly in a passive-aggressive sense than its original meaning? How does this .com-era defining acronym persist through the years, picking up new meanings and uses as it travels around the globe via our interconnected home, the internet? This is what we wanted to investigate– whether passive-aggressive uses of lol have risen in popularity in the past 15 years. Prior to our research, lol’s role as a lexical item has been studied from many different angles. Authors Tagliamonte and Denis (2008) identify the acronym as an interlocutor involvement signal, playing a similar role as “mmhmm” does in face-to-face conversation; denoting that the utterer is engaged in an exchange. Similarly, Varnhagen et al. (2010) found that lol is the pioneer of a new acronym-based lexicon arising from the internet. Markman (2017) also found lol to be a discourse marker, a lexical item that lets a conversation partner know when a statement is done over text. Schneebeli (2020) identifies how the acronym’s placement in a clause can shift its meaning and give statements a new meaning or mood when added. This prior research gives insight to the role lol plays in the syntax and flow of conversations, but, to our knowledge, no studies have chronicled the term’s evolution and shift in use over time. Given that both the internet and the acronym have evolved since its first use in 1989, we feel a current examination is missing from the literature on internet language. Looking at English speaking Twitter from 2008-2022, the salience of lol’s usage as a marker for passive aggression has increased, revealing a broader ability for internet slang to evolve much faster than in-person language due to an abundance of use, communication, the internet’s own growth, and humans finding more of a home online every day.

Methods

To test our hypothesis, we searched Twitter from 2008 to 2022 for tweets that used lol. We gathered 20 random tweets per year for a total of 300. To account for virality as a potential confounding variable, we grouped tweets by how many likes they received and made sure to select 5 tweets per group, per year. We had four engagement groups: Low (0-50 likes), Medium (50-300 likes), High (300-1000 likes), and Ultra-high (1000+ likes). After collecting data from Twitter, we then decided whether each tweet was passive-aggressive and whether lol was positioned clause-final, clause-initial, or somewhere else. To determine whether a tweet used lol to be passive-aggressive we looked at multiple criteria, including lol not signifying its original meaning (“laugh out loud”), whether the tweet conveyed a rude or negative sentiment, whether it targeted a person or situation, or if removing lol lessened the tweet’s attack. Sometimes, we could also look at replies or quote tweets to get more information about the context of each tweet to solidify our decision.

Results

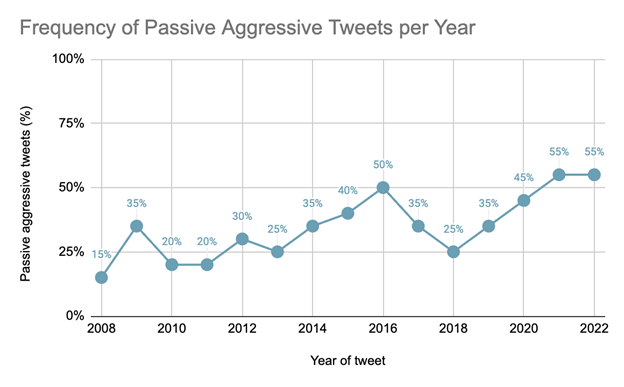

We found that since 2008, English speaking Twitter users have been steadily increasing their use of lol to be passive-aggressive (Figure 1). Using Google-Sheets built-in capabilities, we calculated a Pearson’s r of 0.767, indicating a moderate-strong positive correlation between the frequency of passive-aggressive lols and the year it was tweeted. Our data showed that passive-aggressive lols peaked in 2016 (50%) and 2021 (55%).

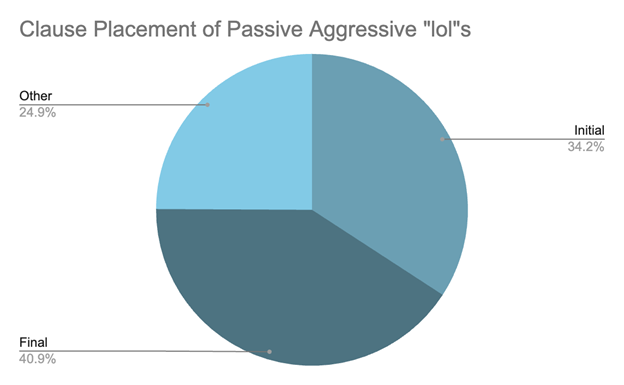

On clause placement, we found that slightly more tweets had lol at clause-final (~41%) than clause-initial (~34%), with about 25% of tweets placing lol in a location indeterminable as final or initial (Figure 2).

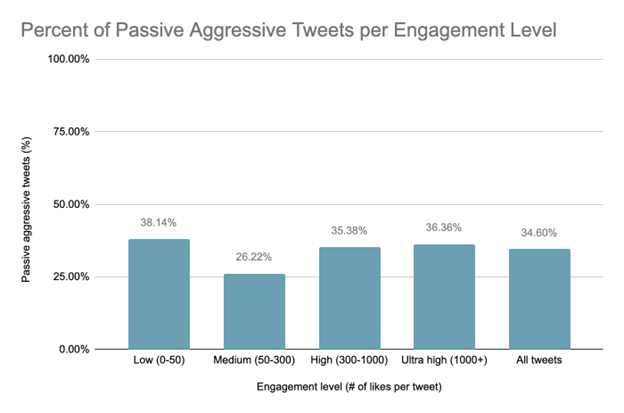

Overall, out of the 300 tweets analyzed, 34.6% were determined to be passive-aggressive uses of lol (Figure 3). For all but one group, we did not find any significant deviation from this number when tweets were grouped in their engagement groups across all years. Among tweets in the Medium group (50-100 likes), 28.6% were determined to be passive-aggressive uses of lol.

Discussion and Conclusion

Due to our data displaying a moderate-strong positive correlation, we concluded that the use of lol to convey passive-aggressiveness increased from 2008-2022. We observed peaks of passive-aggressive tweets during 2016 and 2021. While we are unsure why those peaks occurred during those years, we hypothesize that it was due to political and social turmoil in America. 2016 was when Donald Trump was elected president, and that divided our nation. 2021 was also when COVID evolved into Omicron, and America was again divided on whether wearing a mask was an infringement of our rights. Such factors could influence the use of passive-aggressive lols, and this trend might be an area for future research. We also analyzed the clause placement of passive-aggressive lols and found that the majority appeared clause-finally at 40.9%. Clause-initial lols appeared at 34.2%, and the rest were considered in the ‘other’ category in which the acronym was embedded in the clause. This supports previous research in which clause-initial lol tends to serve as a discourse structuring lexical item such as an immediate reaction whereas clause-finally typically suggests a more aggressive demeanor (Schneebeli, 2020). Finally, we analyzed the passive-aggressive lols per engagement level of the tweet to determine if one engagement group had significantly more or less passive-aggressive tweets, and we observed that there were significantly less tweets in the medium group. However, we do believe that that is an outlier since the rest of the cohorts are in the mid-30 % in regard to passive-aggressive tweets.

There were certainly limitations that should be considered alongside our findings. Due to the time constraints within which the research was conducted, only 20 tweets were found per year studied. Ideally, our findings would be derived from a broader sample, and even include other languages aside from English. Constraining the time frame even more, the advanced search feature on Twitter would only display tweets from September to December of each year, potentially creating a bias towards tensions and events during the Fall and Winter months such as elections, holidays, and harsh weather. Additionally, Twitter search would not allow us to filter tweets by the country of origin, only language. Though the site is most popular amongst American users, there is no way to know if the tweet authors were from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, or some other English-speaking individual. Lastly, our study was looking at passive aggression; though one can typically read tension through a screen, since we were not present for all the interactions or posts, we cannot say for certain if the tweet was delivered in an aggressive way. Despite our systematic approach to determining whether a tweet was aggressive, it is impossible to know the tweet authors’ true intentions behind their posts. We cannot say how these limitations affected our data and results but would be curious to have the study done on a larger scale, including multiple languages, and over a larger period.

Nevertheless, lol’s modality is an example of how the internet can accelerate language evolution. Since the term’s creation with the rest of Instant Messaging language, it’s since taken on countless other meanings in addition to signaling passive aggression. This process, which might normally take decades to accomplish, is now achieved in 20 years. This is partly due to the unprecedented availability of other people’s discourse on the internet and online platforms like Twitter. One could read hundreds of tweets every day and the same tweet could be seen by hundreds of thousands of people. This level of contact between speakers catalyzes the creation of slang words and evolution of other terms like lol. Additionally, Twitter’s characteristics as a social media platform encourages widespread adoption of new language forms. Given that it’s mainly discourse-based, users look to the language of other tweets to inform how they should adapt their own language. This emulation of linguistic behaviors can drive language evolution, like we’ve seen with passive-aggressive lols. Although we did not study other internet language acronyms (ROTFL, lmao, etc.), we noticed anecdotally that lol seems particularly susceptible to being adopted for other uses beyond its literal meaning. Perhaps the term’s shortness, broad meaning, and ease to type into a phone screen have allowed it to garner such an expedited evolution. Future research might investigate what makes lol such a linguistic chameleon and why it has remained relevant in cultural discourse to a greater extent than many other IM language creations that evolved at the same time.

Aside from the explicit findings, our study offers broader implications to the field of sociolinguistics. We were able to identify a few studies on lol, but not nearly as many as expected considering the popularity of the term. This study contributes to this burgeoning sector of the field. Lol’s breadth of uses offer a plethora of research topics — we could conduct this study with an entirely different meaning of the term and find something new and relevant to report. In general, there is a deficit in studies of online language use. Nowadays, a message can be sent from Japan to Canada in a matter of seconds, and on Twitter you can see hundreds of tweets from all around the world with a simple scroll of your thumb. As the world grows more dependent on the internet and humans increasingly engage in online communication, studies of this nature are of the utmost importance for the future of sociolinguistics. Lastly, this research topic came from phenomena we have noticed in our day to daytime spent on social media and engaging in digitally based conversations. Sociolinguistics as a field studies language use and the social implications behind it; this study gives validity to anecdotal experiences as a legitimate course of study and provides a deeper understanding of the terms we use daily.

References

Markman, K. M. (2017, October 30). Exploring the Pragmatic Functions of the Acronym LOL in Instant Messenger Conversations, doi: https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/3du86.

Sloan, L., Morgan, J., Burnap, P., & Williams, M. (2015). Who tweets? Deriving the demographic characteristics of age, occupation and social class from Twitter user meta-data. PLoS One, 10(3), doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115545.

Schneebeli, C. (2020). Where lol is: function and position of lol used as a discourse marker in YouTube comments. Discours. Revue de linguistique, psycholinguistique et informatique. A journal of linguistics, psycholinguistics and computational linguistics, 27.

Tagliamonte, S. A. & Denis, D. (2008). Linguistic Ruin? LOL! Instant Messaging and Teen Language. American Speech, 83(1), 3-34.

Varnhagen, C.K., McFall, G.P., Pugh, N., Routledge, L., Sumida-MacDonald, H. & Kwong, T.E. (2010). lol: new language and spelling in instant messaging. Reading and Writing 23, 719–733.