Alex Chen, Dhanya Charan, Madurya Suresh, Yutong Shi

Discourse particles are often used in conversations to facilitate turn-taking. This process may be independent of the epistemic authority, or confidence level, of the speaker. Discourse particles may be used significantly as a turn-taking mechanism, but no more by confident speakers than unconfident speakers. A study was conducted on pairs of UCLA undergraduate students, aged 18 to 22, who had an established friendship of over three months but under three years. Their majors were used to sort them into confident and unconfident roles. After investigation, it was found that discourse markers are not significantly used to signal turn-taking. Furthermore, speakers in both the confident and unconfident roles use discourse particles much to the same extent. This suggests that discourse particles may not play as pivotal a role as formerly accepted in turn-taking and conversation, yet are virtually ubiquitous in speech – although, perhaps they maintain some yet undiscovered function.

Introduction and Background

Conversational turn-taking is a fascinating process that allows individuals to actively engage in conversations and share their ideas. In our study, we delve into the intriguing world of discourse particles and their potential role in facilitating turn-taking in English conversations.

Previous research has emphasized the significance of turn-taking, revealing that people spend an average of three hours a day engaged in conversations (Levinson & Torreira, 2015). Discourse particles play a multifaceted role in the English language, serving various functions such as indicating shifts in turns, transitioning between topics, expressing agreement or disagreement, and signaling the closure of a conversation (Zimmerman, 2019). The contexts in which these discourse markers appear show trends, such as “you know” often conveying hesitation; this also suggests the semantic significance of discourse markers (Farahani & Ghane, 2022). However, the specific role of discourse particles in turn-taking, as well as their connection with confidence levels, have not received comprehensive attention in previous studies, which presents an intriguing problem that we seek to address. Understanding the influence of confidence levels on turn-taking is crucial as it directly impacts the dynamics and balance of conversational interactions. Previous research suggests that a speaker’s level of confidence, which reflects their epistemic authority, can shape their linguistic choices and influence how they initiate and conclude conversational sequences (Mondada, 2013). By comparing the initiation of turn-taking between speakers with varying levels of confidence, we can gain valuable insights into the intricate relationship between confidence and conversational dynamics.

Our research problem focuses on investigating the role of discourse particles in conversational turn-taking and exploring the influence of confidence levels on their usage. Specifically, our study aims to compare the initiation of turn-taking between a speaker who is more knowledgeable and confident and a speaker who is less knowledgeable and less confident. We hypothesize that regardless of their confidence level, both speakers will rely heavily on discourse particles to facilitate the smooth transition between turns. In other words, discourse particles serve as significant tools for turn-taking in both confident and less confident roles.

Through our research, we aim to enhance our comprehension of how discourse particles function in facilitating smooth transitions between speakers. By investigating the connection between confidence levels and the utilization of discourse particles during turn-taking, we aspire to uncover the subtle intricacies of conversational interactions and establish a foundation for more effective and engaging conversations.

Methods

The target population is undergraduate UCLA students, aged 18 – 22 (UCLA, 2020). We recruited in pairs and selected two pairs of native English-speaking students of different majors and the same gender, with an established friendship of at least 3 months, but not more than 3 years. We selected topics based on the students’ majors, allowing one student to be more confident about the topic than the other. The students were also asked how confident they felt in the topic before and after each conversation in order for us to confirm this. The participants then engaged in a conversation with differing confidence levels on the subject. Lastly, we provided a post-participation survey to keep track of all metadata. The data collection method was based on transcribed audio recordings of the conversations between participants. The transcripts were analyzed for the frequency of discourse markers used, as well as the number of turn-taking initiations made by each participant. We used a one sample one-tailed and two sample two-tailed t-test to analyze the data. The one-tailed t-test allowed us to determine if there is a statistically significant usage of discourse markers used to initiate turn-taking in either role, and similarly, the two-tailed t-test allowed us to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the two roles’ usages of discourse markers to initiate turn-taking. The variables used in our statistical model are confidence level and number of discourse markers used; the frequency of discourse markers used by each participant was compared between the confident and unconfident roles.

Results

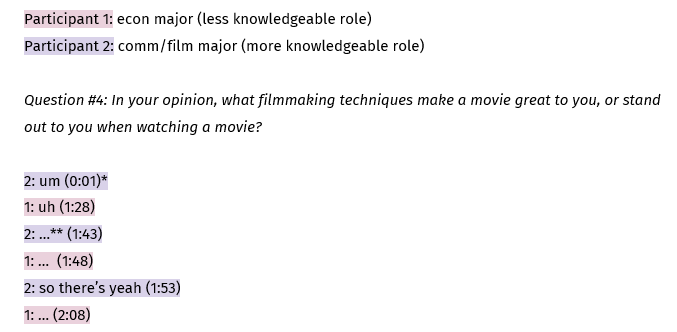

After conducting our participant studies, we selected 4 recordings from each round and transcribed them. Here is an example of part of our transcription for Round 1, Question #4, so you can get an idea of what the transcription process looked like:

*Timestamp from audio recordings

**Note that the “…” denotes a turn taken without the use of a discourse marker to begin the turn.

We didn’t take note of the content of each participant’s answers – we only tracked if they began their turn with a discourse particle, and if so, which discourse particle they used.

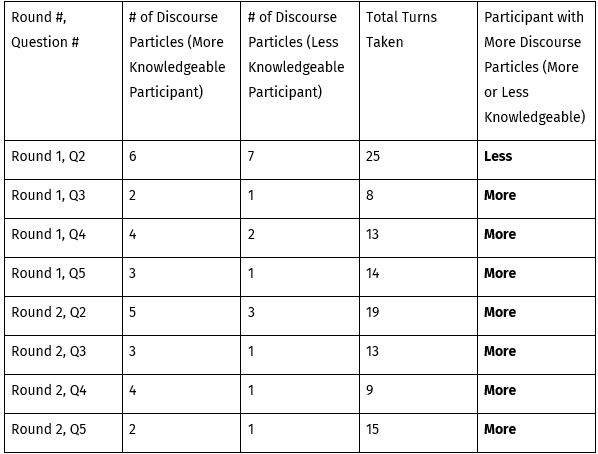

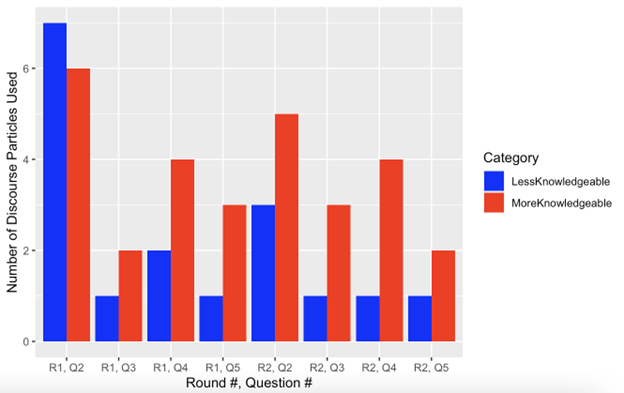

Our data yielded the following results:

This bar graph showing the number of discourse particles used by each participant can help us visualize the results a bit better:

Here, we can see that, overwhelmingly, the more knowledgeable participants in each question in each round used more discourse particles. However, the actual numbers of discourse particles used by each participant is the factor that we will be looking at to determine whether the use of discourse particles in relation to confidence/knowledge levels is actually significant. So, looking at just which participant used more discourse particles in a given conversation (the rightmost column) can be misleading.

Analysis

Just looking at the numbers, the answer to our questions is not immediately obvious. For this reason, we will use statistical analysis to arrive at a sound and statistically-backed conclusion.

The reason being, however, is first, we are not sure whether or not discourse particles have a significance in turn-taking, and we are not sure if confidence levels are a factor in discourse particle usage. For example, in one of the conversations, there were 13 discourse particles used to initiate turn-taking among 25 total turns taken. How can we tell if the usage of discourse particles is actually significant? Although 13 is larger than half of 25, we do not know if it is larger than 50% due to chance, or because discourse particles truly are a significant turn-taking method. For this reason, we have elected to use a One Sample Single Tailed t-test. This test will use our sample proportions and sample standard deviation and compare it to the baseline of 50%.

On the other hand, we are also not sure whether or not confidence level affects the usage of discourse particles in turn-taking. For example, in a different conversation, the more confident role used discourse particles to initiate turn-taking 3 times while the less confident role used discourse particles 1 time. We cannot conclude that being confident increases the usage of discourse particles just because 3 > 1 because this could also be due to chance. To arrive at a sound conclusion, we have elected to use a Two-Sample Two-tailed t-test. This will allow us to determine if the proportions of discourse particle usage between the confident and unconfident roles are significantly different, or if it is due to chance.

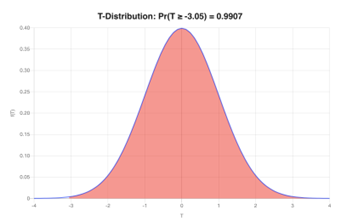

For the first test, we collected the number of turn takes initiated with discourse particles and compared it to the total number of turn takes. This ended up being 0.365. Then, we computed the standard deviation of the entire sample. With these numbers, we are able to calculate a t-score, which ended up being -3.05. This corresponds to a p-value of 0.99. What this p-value means is that given any random conversation, the probability of that conversation having 36.5% or more of the turn takes be initiated with discourse particles is 99%. Thus, the amount of discourse particles we saw being used is not statistically significant. If the p-value was below 5%, we would be able to confidently state that the ratio we found was not due to chance.

This is the curve that shows our t-score distribution. The p-value corresponds to the red shaded area, which is almost all of the area under the curve.

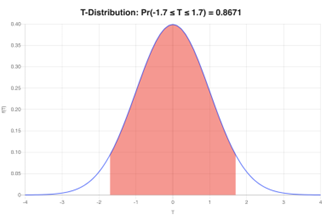

For the second test, we collected the ratio of turn takes initiated with discourse particles compared to the total number of turn takes for each the confident and unconfident role. This came out to be 0.25 and 0.15 for the confident and unconfident roles, respectively. Then, we computed the standard deviation of ratios for each of these roles. Using these numbers, we calculated a t-score of 1.70, which corresponds to a p-value of 0.133. What this p-value means is that given any random conversation with a confident and unconfident role, there is a 13.3% chance that there will be a difference larger than the difference we saw in our data. Because the p-value is still somewhat large (larger than 0.05), we still cannot conclude that confidence plays a role in discourse marker usage in turn-taking.

This is the curve that shows our t-score distribution. The p-value corresponds to the white shaded area, which is a small portion of the area under the curve.

Discussion and Conclusion

Based on our results and statistical analysis, we draw two main conclusions:

- Discourse particles are insignificant when compared to all other turn-taking methods.

- No correlation was found between discourse particles usage and confidence level.

While our sample was random, it was still a very small sample. It could be interesting to explore how our results and analysis may or may not change with a larger random sample size.

An important thing to note is that although we found that discourse particles are not a significant turn-taking method, this is only true when comparing discourse particles to all other turn-taking methods collectively. This conclusion may not necessarily be true when comparing discourse particles to individual other turn-taking methods, such as asking questions.

Beyond the points of interest we explored, we made some observations about our data that could be intriguing to explore further in the future.

Firstly, studying what types of/which discourse particles the participants used could be interesting. We already know from previous research that a participant can use discourse particles, such as “oh” and “you know,” when turn-taking to convey their epistemic state in a conversation. We noticed from our data that, firstly, participants seemed to gravitate to certain discourse particles that were specific to them, no matter the situation. For example, in Round 1, one participant frequently used the discourse particle “uhh” to take their turn, no matter their epistemic state in the conversation. This, along with similar observations about other participants, suggests that choosing which discourse particle to use to engage in turn-taking could be personalized to the individual – or in other words, there are perhaps some discourse particles that people gravitate towards regardless of the situation. But, this is of course only a tentative hypothesis based on our observations.

Furthermore, we noticed that sometimes speakers would “copy” discourse particles from the other interlocutor. For example, one participant would use the discourse particle “yeah,” and the other participant would use “yeah” as well after, especially if the first participant spoke only briefly, and they would keep going back and forth using the same discourse particle. This happened a couple of notable times in our data. It also happened more frequently with discourse particles used for tokens of acknowledgment (which was not what we studied), rather than discourse particles used to begin a turn. Creating an empirical way to test this “copying” phenomenon we observed could be interesting as well.

All in all, based on our data analysis, we concluded that discourse particle usage when turn-taking and confidence level showed no correlation. Still, there’s more to explore within both our research question and the ones that came up through our observations.

When it comes to studying confidence level and methods of turn-taking, what we were really looking for was if there is something unconscious that listeners pick up on that makes a speaker “sound confident,” beyond the actual content of what the speaker is saying. By researching this further through a sociolinguistic framework, we hoped to gain a better understanding of the complex linguistic mechanisms of a regular conversation – mechanisms that we likely don’t take care to notice in our everyday lives!

References

Farahani, M. V., & Ghane Z. (2022). “Unpacking the Function(s) of Discourse Markers in Academic Spoken English: A Corpus-Based Study.” The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 45(1), 49-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-022-00005-3.

Konakahara, M. (2015). An analysis overlapping questions in casual ELF conversation: Cooperative or competitive contribution. Journal of Pragmatics, 84, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.04.014.

Levinson, S. C., & Torreira, F. (2015). Timing in turn-taking and its implications for processing models of language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00731.

Mondada, L. (2013). Displaying, Contesting and Negotiating Epistemic Authority in Social Interaction: Descriptions and Questions in Guided Visits. Discourse Studies, 15(5), 597–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613501577.

UCLA. (2020). Facts & Figures. https://www.ucla.edu/about/facts-and-figures.

Zimmermann, M. (2019). “15. Discourse Particles.” Semantics – Sentence and Information Structure, 511-544. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110589863-015.

Extra Links

Why do we, like, hesitate when we, um, speak? – Lorenzo García-Amaya (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsMWbVrjucg)

Turn-Taking (https://socialcommunication.truman.edu/hidden-social-dimensions/turn-taking/)