Kelly Eun, Isabelle Filen, Adeline Villarreal, Sylvia Le

Engaging in conversation with the man you like may lead you to feel all sorts of emotions. Maybe your heart starts racing, you find yourself laughing at every little thing he says, or you possibly say things you wouldn’t normally say. These are all very common character changes we may go through during these types of situations, but have you ever wondered if speaking to the man you like could also cause changes to your pitch? Our group conducted a sociolinguistic study in order to determine if a woman’s pitch altered while in conversation with a man of her interest, especially within the competitive environment of a dating show such as The Bachelor. With this objective in mind, the three longest running contestants were selected in order to analyze whether there was a possibility of pitch modulation while in one-on-one conversations with the bachelor. Praat was used to input data to find pitch means, as well as to discover if pitch change actually occurred.

Introduction and Background

Some of us may have a preconceived idea in regard to what happens to a woman’s voice when she talks to the man she likes, right? We could ask our friend, parent, or boyfriend to do an impression of a woman flirting with a guy and we would most likely hear something incredibly high-pitched and giddy with lots of giggling and hair twirling. This is a commonly held phenomenon in which a woman’s pitch raises in scenarios where she is interacting with a potential romantic partner (Re et al., 2012).

However, a study done in the UK (Pisanski et al., 2018) found that women on speed dates actually demonstrated a decrease in pitch value when the men they were interested in were in high demand, even highlighting how lower-pitched voices were more favorable than their higher-pitched counterparts. Why did they find a decrease in pitch? This is precisely what our group sought to uncover through our research, as we also asked ourselves…why?

To better understand typical traits associated with pitch, we discovered that higher-pitched voices are commonly indexed with fertility, youth, and femininity (Apicella and Fienberg, 2008)—all the traits men seem to absolutely swoon over, right? However, there might be some other traits men seem to be entranced by as well, such as sexual explicitness, seductiveness, dominance, and authority (Klofstad et al., 2012); such traits are also associated with a lower-pitched voice (Fraccaro et al., 2013).

Thus, we hypothesized that when we look at the average pitch values of our target population in our targeted scenario (which will be uncovered in our methodology discussion), the average pitch values of the contestants will be lower when they feel insecure of their position in the competition and higher when they feel more secure. The question we asked and pursued the answer to was the following: Does a lower pitch truly index the contestants’ desire and motive to assert their dominance through embodying a seductive, authoritative character who deserves not only a spot in the competition, but also the bachelor’s heart?

Methods

For our study, we first selected three women from Season 22 of The Bachelor (labeled as Contestants A, B, and C) who would remain for the longest duration, resulting in the selection of the winner, runner-up, and the “third place” contestant. We specifically chose these women because it allowed us to collect consistent data from the same three contestants throughout the whole season.

To analyze Contestants A, B, and C’s pitch across the entirety of Season 22, we divided the season into three stages: beginning (episodes 1-4), middle (episodes 5-7), and end (episodes 8-11). Pitch refers to the frequency of the sound waves made by a voice’s vibration. For instance, higher frequencies indicate higher pitch.

We then collected two utterances (e.g. brief comments) made by each of the three contestants per stage, for a total of 18 utterances (6 for each woman). To avoid the pitch being influenced by other voices, we only recorded utterances from one-on-one conversations between each of the contestants and the bachelor. The first utterance (Utterance A) was made by recording what the contestant had said before she received assurance from the bachelor, and the second (Utterance B) was made by recording what the contestant had said after. For the sake of this project, we not only considered comments such as “I like you too” or “I love you” as assurance from the bachelor, but we also took into consideration that a kiss could also be perceived as non-verbal assurance.

Afterwards, we separately inputted each utterance recording from each contestant and stage into Praat to determine if there was a change in pitch before and after Contestants A, B, and C received assurance from the bachelor. Praat is a software tool used in linguistic research to examine speech; in this specific study, we used it to analyze pitch. Rather than maximum pitch, the mean pitch values for Utterance A and Utterance B were used in order to account for possible pitch peaks and outliers that could arise and skew the pitch results. This would include a rise in pitch to indicate the end of a question or a potential fall of a declarative statement. So, utilizing the means of pitches provided a bigger picture.

Results and Analysis

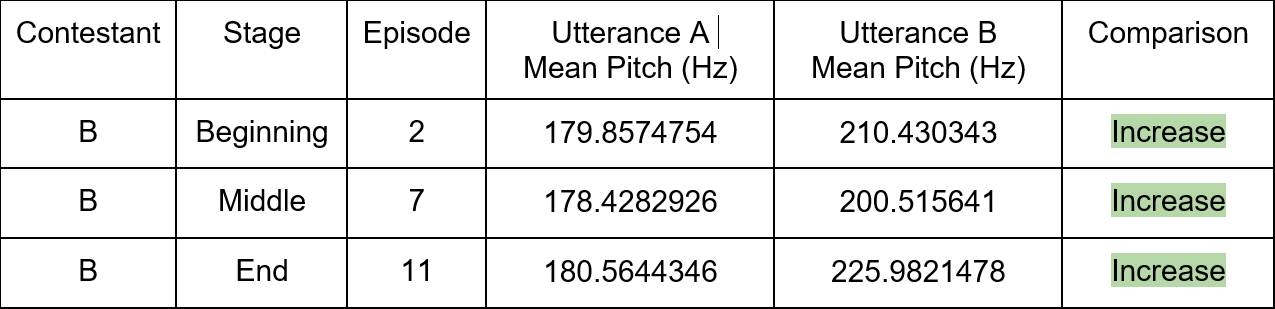

Throughout the course of Contestant B’s run on the show, our group found a consistent increase in pitch, as evident by the table below.

Our data for pitch mean is measured in hertz (Hz), the standardized unit of frequency equal to one cycle per second. Sound frequency is determined by how waves oscillate while they travel to our ears and when the oscillation of frequency waves is higher, we hear a higher pitch.

The table shows a positive difference between Utterance B Mean Pitch and Utterance A Mean Pitch in hertz in all three stages of the competition (beginning, middle, and end), indicating that the pitches of Contestant B became higher after assurance from the bachelor. Based on our background research, this likely indicates that Contestant B became more relaxed after assurance during her conversations with the bachelor.

Additional research was conducted to find that Contestant B was the eventual winner of Season 22 of The Bachelor, meaning that she was proposed to by the bachelor in the final episode. Our group predicts that this likely contributed as a factor for the increase in her pitch, as she was one of the frontrunners of the competition.

However, it is also important to note that it is difficult to make definite inferences about how Contestant B was feeling confidence-wise as the competition progressed. For example, it is possible that she could have felt more relaxed, knowing that there were less women competing against her; contrastingly, it is also possible that the stakes became higher for her, and she felt more possessive or competitive with the remaining women.

Another important factor in the data for Contestant B is that specifically in episodes 2 and 7, Contestant B received a rose during a date from the bachelor, which is a rare occurrence as roses are typically offered during elimination “Rose Ceremonies.” The offer of this rose in addition to the lead-up to it could also have had an effect on Contestant B’s confidence, further playing a part in her pitch raise as an indicator of her ease.

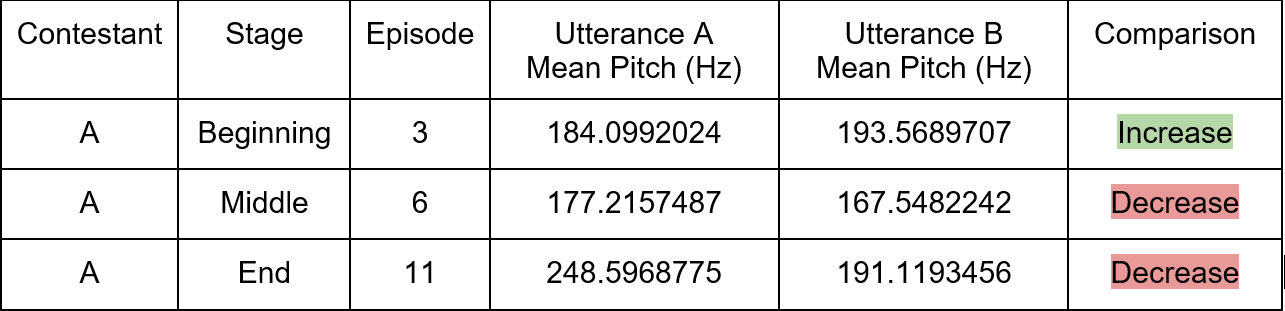

When it comes to Contestants A and C, both of these women demonstrated instances where the changes of their pitch decreased (i.e. their pitches before getting a response from the bachelor were higher than their pitches after), as opposed to the increase we were anticipating. Let’s first take a look at Contestant A, whose middle and end pitch means had a decreasing comparison.

Looking at Table 2, we can see how Contestant A’s beginning stage pitch comparison was in alignment with our hypothesis. When she started her one-on-one conversation from that segment of the episode, her Utterance A had the mean pitch of 184.0992024 Hz. After the bachelor chimed in, the mean pitch of her reply was higher than before at 193.5689707 Hz. We found that this could be due to Contestant A feeling reassured by what the bachelor had said, which could have further contributed to her feeling less concerned about her placement in the competition and not as worried about having to modulate her pitch or portray a sensual appeal.

Let’s now take a look at Contestant A’s middle stage pitch comparison, which contrasts the comparison result of her beginning stage. While she had begun the conversation from this segment with a mean pitch of 177.2157487 Hz, this dropped to a mean pitch of 167.5482242 Hz after the bachelor had his turn of speaking to her. With cases like this where the contestant’s pre-assurance mean pitch value is higher than their post-assurance value, it may have been because what the bachelor had said to the contestants contributed to their feelings of uncertainty with both their relationship and place in the competition. By responding to the bachelor with a lower-pitched voice, it would be more likely to project more authority, which could strengthen their relationship with the bachelor and assert their reason to remain on the show.

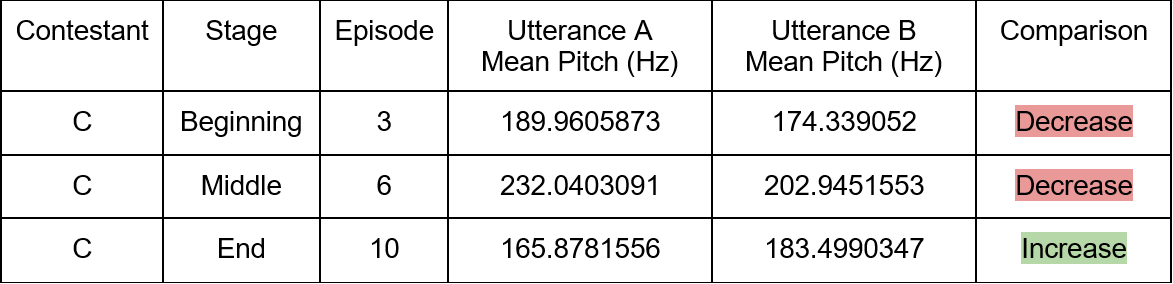

Moving onto Contestant C, we can see in Table 3 that she also had two of her three pitch mean comparisons being a decrease like Contestant A.

Interestingly enough, whereas Contestant A’s mean pitch comparisons throughout the stages went from an increase to two decreases, Contestant C’s progression was in the reverse order of Contestant A’s and went from two decreases to an eventual increase by the end of the season. This development could possibly be due to Contestant C gradually reaching a place in her relationship with the bachelor that solidified her confidence, while Contestant A may have felt more hesitation with hers. It is important to note that in all of these utterances, although we used our best judgment to decipher the scenarios and contestants’ reactions, there may have been other factors outside of the ones we targeted that contributed to the pitch outcomes of these women.

Discussion and Conclusion

Upon gathering and analyzing our results, our group was able to determine that while our data somewhat aligned with our aforementioned hypothesis, the results may not have been as consistent as we previously imagined. With the conclusion of our research, we then began to account for potential limitations to the big picture we desired to paint as a result of our findings.

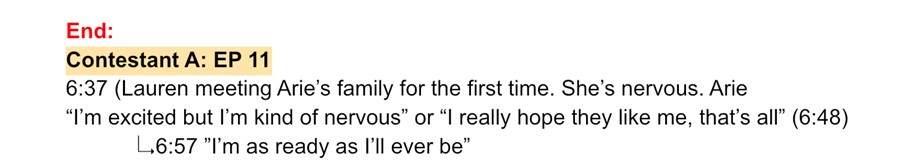

For example, we encountered a scenario with Contestant A in the end stage of the competition where her pitch began high. According to the scope of our project, this should indicate that her confidence level was high. However, after receiving an assuring statement from the bachelor, her pitch actually dropped, meaning that she felt less confident by the end of the interaction. An example of this scenario is shown below in Figure 1.

To account for this limitation, we attempted to think outside the realm of our project and dig a little deeper as to what factors could have led to this particular utterance not aligning with our hypothesis, and we may have gotten our answer from looking into something almost all of us have probably done at least once in our lives: lied.

Let’s say your boyfriend made you upset and finally mustered up the courage to ask the dreaded question: “Are you okay?” You look him dead in the eyes, clearly not okay, and say something along the lines of “I’m fine” or “I’m just tired.” Now, are you really fine or just tired? Absolutely not, but for reasons unbeknownst to everyone but the universe itself, you evaded the truth. Similarly, this could have been what we saw in our data as well.

Therefore, even though we used our best judgment to select a scenario in which the contestant received verbal assurance, when we consider the limited scope of our sociolinguistic research, we may not have been able to account for the internal psychological factors that pertain to a woman’s verbal expression of having accepted that assurance. Thus, as we saw in Contestant A’s final utterance, we presumed that her response of “I’m as ready as I’ll ever be” indicated to the listener that she has been assured and is feeling ‘ready’ to meet the bachelor’s family for the first time. Ideally, this should have been accompanied by a higher pitch to index her confidence and security in the competition. However, we can now presume that Contestant A’s statement did not actually reflect what she was feeling inside and she may have felt as though she was nowhere near ‘ready’ to meet the bachelor’s parents, thus explaining why her confidence level and (consequently) the mean pitch were lower by the end of her utterance, which actually does align with our hypothesis! If we had not calculated the mean pitch of this utterance or discovered an unexpected decrease that misaligned with our hypothesis, we would have not been able to think beyond the realm of our research and propose an internal factor that may have impacted what we found in our results. So, what our group initially identified as a suspected failure may not have been a failure at all.

Furthermore, our group looked beyond the bindings of our research and constructed further possible iterations of our project that could be used to bridge the gaps in both previous research and our project on pitch modulation and its indexicality. These iterations could dive into many possible examinations of pitch modulation such as mental/physical well-being, age of the target population, the presence of vowel shifting, and even examining a scenario in which the woman contrarily is not interested in the man she is interacting with. The inclusion of all of these external and, as we know now, internal factors could certainly come together and paint a clear and concise picture of this phenomenon, as it is one that certainly cannot be attributed to just one definitive variable.

References

Apicella, C. L. & Feinberg, D. R. (2008) Voice pitch alters mate-choice-relevant perception in hunter-gatherers. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 276(1659), 1077–1082. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.1542

Fraccaro, P. J., O’Connor, J. J. M., Re, D. E., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., & Feinberg, D. R. (2013) Faking it: Deliberately altered voice pitch and vocal attractiveness. Animal Behaviour 85(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.10.016

Klofstad, C. A., Anderson, R. C., & Peters, S. (2012) Sounds like a winner: Voice pitch influences perception of leadership capacity in both men and women. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 279(1738), 2698–2704. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41549338

Pisanski, K., Oleszkiewicz, A., Plachetka, J., Gmiterek, M., & Reby, D. (2018) Voice pitch modulation in human mate choice. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 285(1893), 20181634-20181634. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1634

Re, D.E., O’Connor, J. J. M., Bennett, P. J., & Feinberg, D. R. (2012) Preferences for very low and very high voice pitch in humans. PloS one, 7(3), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032719