Sarah Thomas, Emma Greene, Cameron Brewer, Jamie Dela Cruz

With 2020 fast approaching, everybody has their eyes on the many candidates running for president, calling into attention how they frame particular issues to gain public support. The mixed-gender debates within the Democratic party raise the question of how this new dynamic will affect future political conversations. However, it’s no secret that women have a harder time making themselves heard, with their gender inspiring the public to maintain traditional stereotypes about them.

Existing gender inequalities, or sexism, persist in language, and can be maintained through the speaker and their audience (Suleiman & O’Connell 2008). In this context, the relationships with a candidate to other candidates and the public reflect a power dynamic that women must handle to assert their own place in the political sphere. To understand how these candidates navigate mixed-gender debates, we looked at one of the Democratic primaries, paying special attention to what language tactics they used.

Introduction

The United States is a melting pot of individuals with unique backgrounds, cultures, and ideals. However, this diversity is not adequately reflected in the country’s political realm. One such identity that is not equally represented is that of women; despite making up over half of the United States’ population, women represent a mere 23.6% of congressional office (Rutgers 2019). Gender politics is essential to help explain why women are so underrepresented in elective offices.

Every speech, conversation, and debate is thoroughly analyzed, critiqued, and judged by the press and public. With the upcoming Presidential election, the Democratic party’s mix-gendered political debates create a distinct dialogue between candidates and with their audience.

Politicians are intentional with their language, having a team of writers work with them to decide how they want to speak about a particular issue. In the context of gender, some linguistic functions are perceived as linked to one gender more than the other; this association gives rise to potential stereotyping of politicians based on how they speak, not their politics (Suleiman & O’Connell 2008). Communication differences and gender communicative patterns have been found to link specific traits with gender (Grebelsky-Lichtman & Katz 2019).

The present study seeks to better understand how gender communication structures of women and men in politics compared to one another in terms of usage and relate these findings to press and public reaction.

Background information

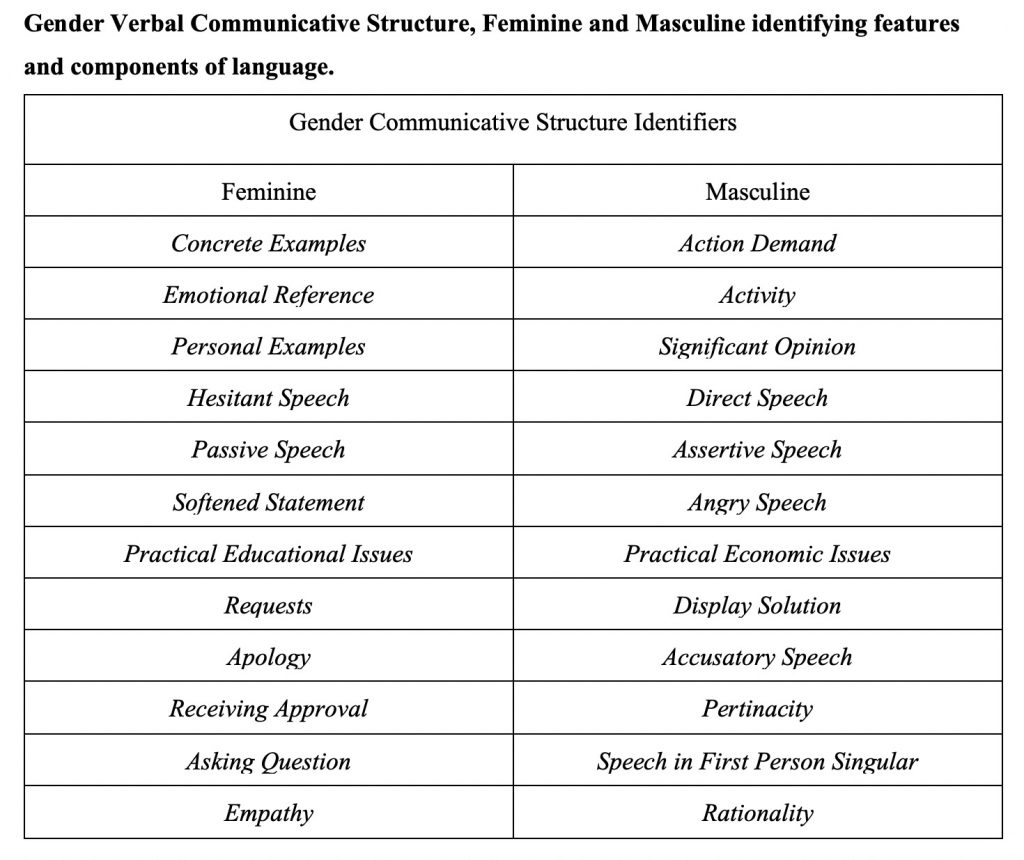

In a study that looked at how much women and men spoke, it was found that even though women speak less than men, men lashed out when they believed there were more women talking than them. This discovery emphasized the idea that men truly dominated public talk and pushed back when women tried to gain equal footing (Mooney & Evans 2015). Multiple studies have found a relationship between patterns in communication differences and gender, which are summarized in the following table (Grebelsky-Lichtman & Katz 2019).

Methods

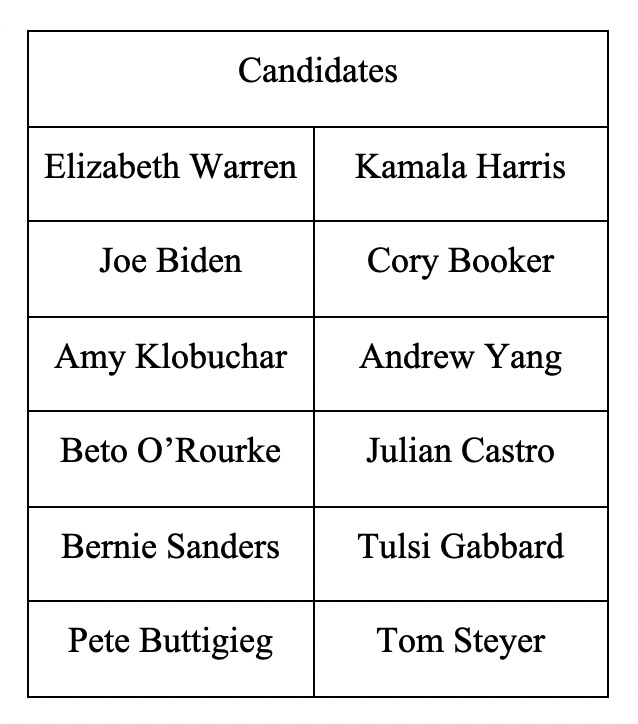

The project design investigated how politicians spoke in a mixed-gender debate, specifically the October 15, 2019 Democratic Primary Debate.

Using the video recording and online transcript provided by CNN and the Washington Post, the candidates were considered individually and compared with each other. He or she was analyzed for feminine and masculine identifiers, based on Grebelsky-Lictman and Bdólach’s verbal gender communicative accountability framework, and received a mark for each unique use of the aforementioned linguistic features (2019).

After averaging how frequent each gender and each individual candidate used communicative identifiers, the speaking styles of the top and bottom-rated candidates of both genders were examined to determine whether there was a relationship between communicative patterns and public appeal.

The purpose of analyzing political candidates in the context of gender-oriented communication is to answer the following questions:

-

- How do the gender communication structures of female and male American politicians compare?

- What, if any, masculine communicative structures are most commonly used by females? What, if any, feminine communicative structures are most commonly used by males? In these instances, are structures that are used equally by both females and males more gender-neutral?

- Are a candidate’s polling numbers related to which opposite gender communicative structure they use?

Results

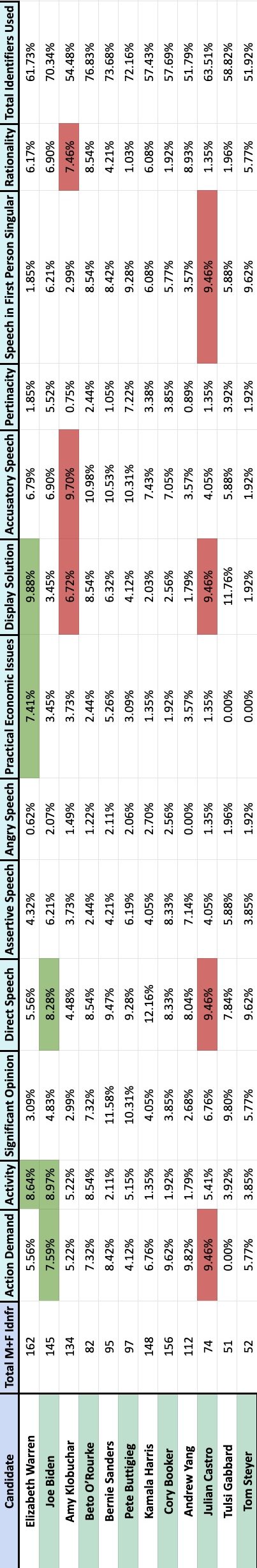

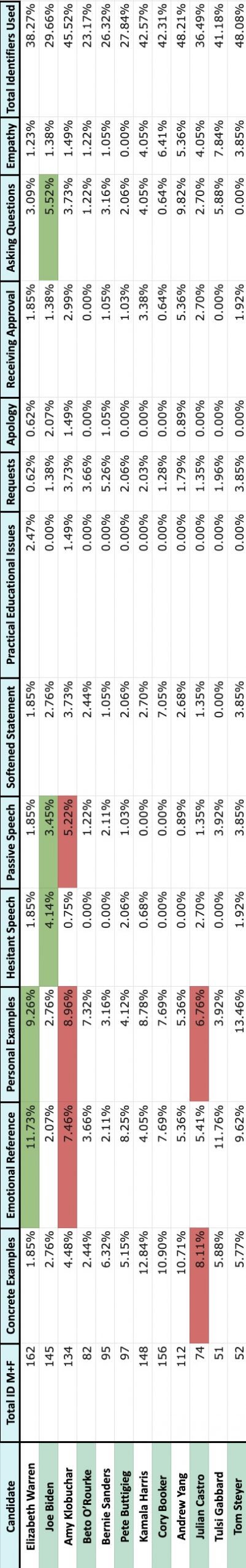

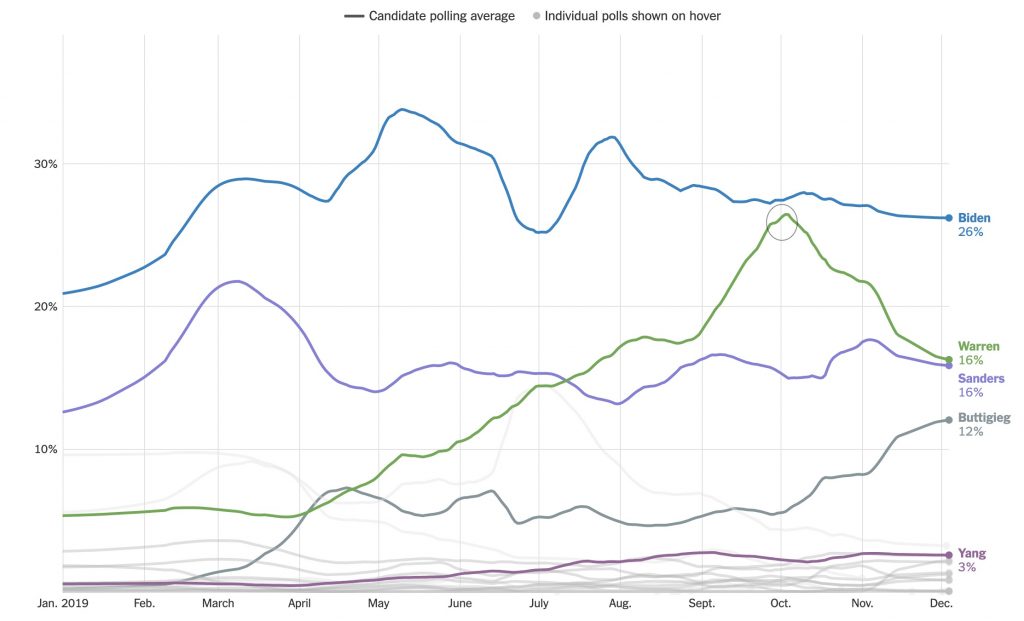

From New York Time’s Democratic Polling Data, we found Elizabeth Warren to be the top female candidate and Joe Biden the top male candidate. A total of 61.7% of Elizabeth Warren’s speech patterns were considered masculine, while Joe Biden’s speech patterns had a ratio of 70.3% that were masculine-identified. When comparing the usage of specific identifiers, Warren favored emotional reference, personal example, display of solution and practical economic issues. Biden favored assertive and direct speech, pertinacity, and speech in first person, singular.

When comparing Castro, the lowest polling male candidate, to Biden, we found that his main masculine identifiers consisted of action demand, direct speech, display solution, and speech in first person singular. Similarly, Biden’s consisted of activity, direct speech, and action demand. When examining their feminine identifiers, Castro primarily used concrete examples, personal examples, and emotional reference, whereas Biden used hesitant speech, passive speech, and questions.

Klobuchar, the lowest polling female, primarily used accusatory speech, rationality, and display solution as her masculine identifiers, while Warren used display solution, activity, and practical economic issues. Both used emotional reference and personal examples as their primary feminine identifiers.

Discussion and conclusions

With this being the fourth debate in the race for the Democratic nomination, the public is familiar with each candidate’s communication style by now. Interestingly, it can be seen from the following graph that Elizabeth Warren’s likability, or public appeal, was projected to dramatically increase, which it did: she began with 5% support, and following the October debate, it rose above 20%.

In terms of feminine communication structures, Warren focused on emotional reference and personal examples over five times more often than Biden. It is clear that despite Biden’s use of identifiers, they were commonly used as a pause to gather his next thought, not as part of his argument. With feminine speech being associated with more passive and hesitant behavior, we suspect that using personal example and emotional reference are effective identifiers that don’t hinder perceived competence. However, it is also significant to note that because Warren utilized masculine identifiers such as significant opinion or action demand, they were used more as persuasive, support gathering tools.

Warren dominated over all other candidates, including Biden, with her constant usage of masculine identifiers, such as display solutions and references to practical economic issues. Biden dominated in more aggressive and assertive language, using direct speech, pertinacity and speech in first person singular. While Biden can use aggression to show strength and leadership, when a woman uses aggression, the public reaction is widely different. Aggression in female communication patterns is portrayed more often emotionally unstable outbursts or unlikeability, or even “shrilly.”

Despite their drastic differences in polling success, Biden and Castro had extremely similar masculine identifiers: assertive speech and action demand. What seems to truly set these candidates apart is their use of feminine identifiers; Castro’s feminine identifiers functioned more emotionally and anecdotally (concrete examples, personal examples) and Biden’s were more passive (hesitant speech, passive speech). This implies that males are judged more on their usage of feminine speech than masculine speech. Also, there is a question of whether men are judged more for their feminine identifier use than women. Specifically, while Castro’s main feminine identifiers were identical to Warren’s, they proved to be much less effective for Castro than for Warren.

When comparing the top and bottom-rated female candidates, Klobuchar also employed the same feminine identifiers as Warren; however, their masculine identifiers differed. Warren exhibited a more calm demeanor, focusing on practical masculine identifiers (activity, practical economic solutions, display solution). Klobuchar’s reliance on accusatory and emotionally-charged masculine identifiers proved less effective in the public’s eyes.

What set the top and bottom candidates of each gender apart was their use of identifiers that were typical of the opposite gender. It makes sense that the public will more closely analyze communicative patterns that are atypical of a candidate’s gender when forming an opinion about them.

Will we ever have a female president? After the unexpected upset of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Election, strong opinions formed regarding the deciding factor that led to Trump’s victory. Many people claimed the result was due to sexism in the U.S., while others summed it up to Hillary’s lack of likeability.

What if these things are just extensions of how each candidate chose to present themselves? Hillary often used very aggressive masculine identifiers, as Trump did, but what really separated them was the perceptions the public had of both of them. For women, as shown in one of Trump’s tweets, aggression and anger is viewed as a sign of weakness, while aggression in male candidates is validated and expected.

This adds to a common theme in which the effectiveness of identifiers is very context specific, depending on the gender of the candidate, their intended audience, etc. These linguistic double standards add up, and although the message the candidates are trying to convey, much of their impact on the audience has to do with the way they present their messages, and their personal identity that impacts the potential voters.

READ THESE NEXT

More on the October 15, 2019 Debate:

Want this article in powerpoint form? We’ve got you.

The Fourth Democratic Debate in 6 Charts

2020 Presidential Race from the Democratic Side:

NY Times: Which Democrats Are Leading the 2020 Presidential Race?

NPR: Tracking the Issues in the 2020 Election

Statistics of Women in Elective Office

Referenced Journal Articles:

Grebelsky-Lichtman, T., & Bdolach, L. (2017). Talk like a man, walk like a woman: an advanced political communication framework for female politicians. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23, 275–300. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2017.1358979

Grebelsky-Lichtman, T., & Katz, R. (2019). When a man debates a woman: Trump vs. Clinton in the first mixed gender presidential debates. Journal of Gender Studies, 28, 699–719. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1566890

Suleiman, C., & O’Connell, D. C. (2008). Race and gender in current american politics: A discourse-analytic perspective. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 37(6), 373-389. doi:10.1007/s10936-008-9087-x

Mooney, A., & Evans, B. (Eds.). (2015). Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. (4th ed.).