Layla Hernandez, Yasleen Robinson, Charlotte Norris

Throughout their lectures, professors typically engage with their students. This process often requires the professors to implement certain linguistic devices in their speech that allow for them to sound less aggressive and threatening. These linguistic features include forms of hedging. Both male and female professors rely on hedges to further display politeness when interacting with their students. In this study, we focused on how professors utilize these hedge words in ways that promote themselves in ways that are more approachable and less authoritative. We hypothesized that female professors would utilize hedges more than their male professor counterparts. Specifically focusing on the frequency of the usage of hedge words, we analyzed four sociology professors from UCLA through recordings after attending their lectures. We carefully listened to each audio and transcribed them through Conversational Analysis (CA) to further allocate the number of hedges they used when speaking with their students. A detailed analysis revealed that male and female professors do not yield significant patterns in their uses of hedges. In fact, they used them very similarly in terms of frequency and style.

Introduction

For our project, we investigated the hedges that are used by both women and men professors during their interactions with their students during their lectures. More specifically, we aimed to highlight how the usage of these linguistic markers help to ease the declarative statements they share with their students. We hypothesize that the women professors will hedge more frequently throughout their discussions with their students because hedging is unequivocally involved and ingrained in women’s speech (Lakoff, 1972). We also hypothesize that both male and female professors will utilize hedging as a means to soften their assertive/strong statements to further promote interpersonal interaction and more inclusivity within the classroom.

Background

Professors and their approaches hold great influence over the success of their students. In this way, they consciously work to provide interpersonal interactions with their students while also actively working to supply a learning environment that is inclusive and welcoming (Van Petegem et al., 2005). This process typically requires the professors to employ linguistic strategies that portray them to be less threatening and aggressive through their choice of words (hedging). Hedges are words or utterances that serve to “reduce the force of a statement” (Wright & Hosman, 2009, p. 143). The professor’s reliance on hedge words prevents them from sounding or behaving like they know everything, rather it serves as a buffer that allows for a response or objection. In this way, professors create an open forum in which students feel comfortable probing or questioning the content they are teaching without fear of judgment. Our focus will also turn to the gendered patterns of hedging among men and women professors, specifically focusing on who uses hedges more frequently.

Methods

Our main focus included examining instances of hedging and their role in yielding the authority of professors in student-teacher interactions. We focused specifically on UCLA professors in the Sociology department to avoid linguistic variation that could occur due to variations in lecture content. We collected recordings from 4 different Sociology professors at UCLA which will include three males and 1 female. We collected our data through audio recordings after attending 4 different lectures, where we keyed in on student and professor interactions. We extracted our data from two interactions from each lecture. Where we then transcribed each exchange through Conversational Analysis (CA). Through this form of analysis, we highlighted the different hedges that both female and male professors use to soften their strong statements when speaking to their students. To achieve this, we looked at each transcript individually to identify patterns specific to each professor followed by a comparison between professors of the same gender and then across genders to look for any similarities or differences that are connected to larger gendered-language patterns. We also wanted to measure the frequency of how many times each hedge word was used by each professor. Thus, after transcribing we allocated the number of hedge words they included in their interactions.

Results and Analysis

Interestingly, our results indicated that there was not a significant pattern when comparing hedge use between female and male professors. Our initial hypothesis that women would produce more instances of hedging when interacting when students in comparison to male professors was completely in misalignment with our results. In contrast, we found that both genders utilize hedges in similar ways that would further elevate their statements from sounding too forceful or impolite. We also found that in terms of frequency, male and female professors depend on the practice of hedging similarly. There wasn’t a significant pattern that demonstrated that one gender utilized the linguistic device more than the other. If anything, it dispels the common notion that women rely on hedging more than men because we see that is not the case here, both genders rely on hedges almost equally.

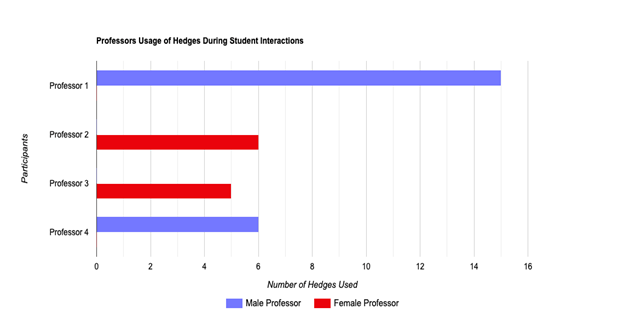

Our first participant, professor 1, was unique because he was the only male as well as the only professor to demonstrate a wide and dependent use of hedging when interacting with his students. The bar graph above illustrates how professor 1 drastically differs from the other professors when examining their reliance on hedges during their interactions with their students. After completing professor 1’s (CA), we found that he accounted for a total number of 15 different instances of hedging. Each professor yielded some form of hedging, however, it seems that professor 1 superseded every other professor in terms of hedge use. After comparing him to the other professors that did not align with this pattern, we connected his use of hedging to his linguistic style and postulated that hedging may be a central linguistic feature in his everyday speech.

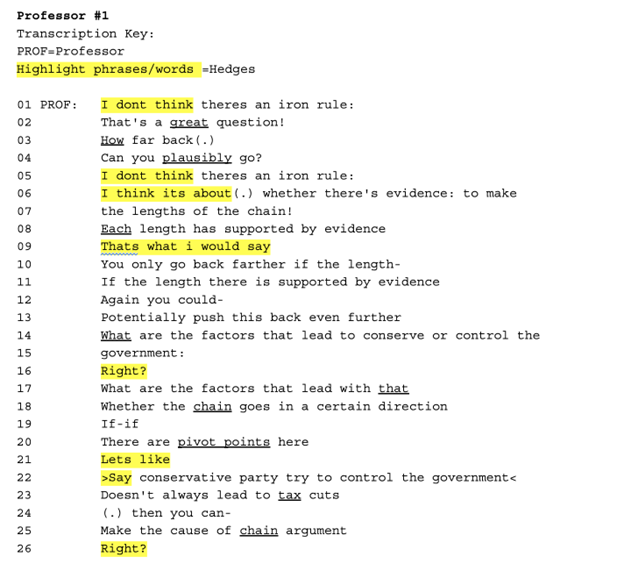

In the (CA) extracted from Professor 1’s (male) lecture, you can see a handful of the hedge words he used while engaging with his students. We classified his frequent use of the word “right” as a hedge word because we noticed that he would insert them right after finishing his strong and declarative statements. It was apparent that he depended on “right” as a means to establish an open forum that allowed for the student to respond or interject. We also interpreted his usage of “right” as a way to provoke silent agreement. This hedge word was especially important when interacting with other students as the professor relied on it with each interaction he made with his students. We also highlighted that the professor used the hedging phrase “I don’t think” several times as well. It was very clear to us that he depended on this phrase as a means of expressing uncertainty. This is an important practice because professors work to avoid behaving or sounding like they know everything because it leaves room for students to object, gauge, or comment on their statements.

In contrast, Professor 2, 3, and 4 all displayed significantly less instances of hedge use during their interactions in comparison to Professor 1. In contrast, professor 2 (female) and professor 3 (male) included hedge words 6 times whereas professor 3 (female) only displayed 5 instances of hedges when engaging with her student. Our findings indicated that both genders relied on hedges similarly, in terms of numbers and surrounding context. Each professor integrated some sort of hedge word in ways that lessened the force of their statement, signaled agreement, or expressed cautious uncertainty.

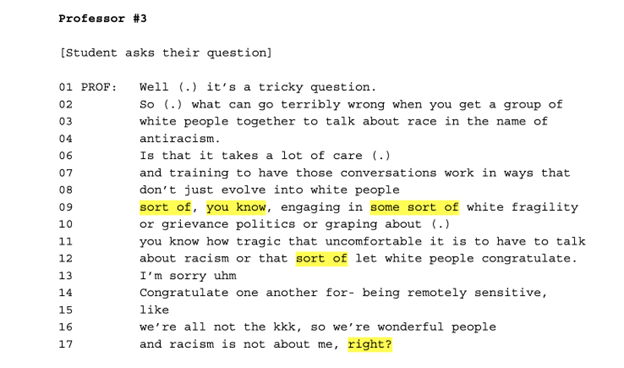

For instance, as depicted in the conversational analysis above professor 3 (female) sporadically included hedges like “sort of” and “you know” to soften her claims and statements. We concluded that she turned to this linguistic variable to display politeness and avoid authoritative brute force that would make her sound less approachable and more aggressive. This approach allowed for a fluid and authentic interaction when replying to an inquiry made by her student, one that didn’t involve the professor imploding information on the student but rather one that left room for doubt and allowed room for responses, objections, and even interjections.

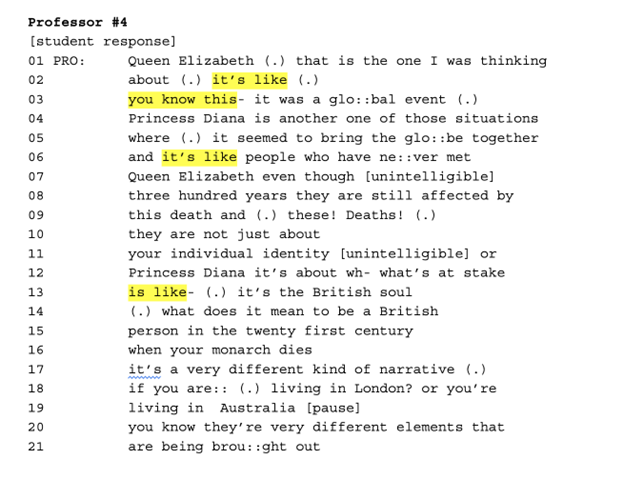

Similarly, Professor 4 (male) employs the linguistic device to lessen the magnitude of his assertions. The (CA) above shows that he utilized the phrase “it’s like” on three different occasions to display some sort of indirectness. We deemed the phrase as an instance of hedging because he used it to ease his claims so that he didn’t sound overly forceful or assertive. We also derived the conclusion that he could be employing this device as a way to create an inviting forum for further commentary or inquiries. After gathering our observations, we found that each professor depended on hedges in ways that further display themselves along with their statements as more polite to steer clear from sounding rude or unapproachable. Some obviously more than others but regardless this linguistic variable enabled them to engage with their students in an authentic and less authoritative manner.

Discussion and Conclusion

To conclude, our results revealed that both male and female professors utilize hedging to soften their statements. We found that professors exhibited hedging as a means to soften their statements to some degree in their speech. Professors 2, 3, and 4 used hedging in similar amounts and Professor 1 stood out as an outlier in his much more frequent use of hedging. This finding contradicts our hypothesis that female professors would hedge more frequently than men. It also contradicts Lakoff’s (1972) findings and his claim that hedging is an integral part of women’s speech, so much so that women hedge more frequently than men. If our findings had been in alignment with Lakoff (1972), we would have seen female professors hedge more frequently than male professors but that was not the case.

While we did not find noticeable differences in use of hedging on the basis of gender, further analysis of our data with a less specific focus on a particular linguistic variable could reveal patterns that are not visible when the scope is narrowed on one variable. Our study was faced with multiple limitations that may have affected the outcome. With a larger sample of professors and more time to analyze the data, patterns that couldn’t be found or generalized with such a small sample could emerge. Our teaching population was also limited to one subject (sociology) and one educational setting (large university). An analysis across subjects or in different educational settings that have different goals for students might have led to different results.

There are a few other explanations for our findings and directions that our study could be taken in. Perhaps there were no noticeable patterns across male and female professors because professors have different styles of engaging students during interactions. Professor 1 (male), who hedged noticeably more than his colleagues, may choose to engage his students in direct interaction through hedging while the other professors may choose other linguistic tools to achieve the same goal. It is also possible that these professors are not focused on creating an inclusive lecture through student interaction and instead attempt to foster engagement through other parts of their lecture, resulting in a lack of hedging in their speech. Maybe their focus is not on creating an inclusive environment and rather each professor has a unique goal in the classroom that further influences their style of communication.

Furthermore, our findings raise some important questions concerning gender dynamics in teaching and in other social contexts. The Lakoff (1972) study demonstrated that gendered linguistic patterns do exist in some social contexts, but our research did not find this pattern in one particular context of university teaching. Perhaps, our findings could influence or lead to further research that could investigate how gendered speech patterns that have been documented in some contexts (e.g. hedging) appear in other social contexts such as other professional environments, in conversations between established friends, or conversations between strangers.

References

Lakoff, Robin. (1972). Language and Woman’s Place. Language in Society, 2(1), pp. 45-80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4166707?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Oliveira, A.W., Sadler, T.D., Suslak, D.F. (2007). The linguistic construction of expert identity in professor–student discussions of science. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 2, pp. 119-150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-006-9039-4

Van Petegem, K., Creemers, B. P. M., Rossel, Y., & Aelterman, A. (2005). Relationships Between Teacher Characteristics, Interpersonal Teacher Behaviour and Teacher Wellbeing. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 40(2), pp. 34–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23870662

John W. Wright II & Lawrence A. Hosman (1983). Language style and sex bias in the courtroom: The effects of male and female use of hedges and intensifiers on impression information. Southern Journal of Communication, 48(2), pp. 137-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417948309372559

Zakia, Anisa (2018) Pragmatic study on hedging as politeness strategy in online newspaper. Universitas Islam Negeri, pp. 13. https://repository.uinjkt.ac.id/dspace/handle/123456789/45815