Kayenat Barak, Emily Moreira, Sae Tsunawaki, Karin Yamaoka

While social media has been a revolutionary tool for facilitating access to resources and information and connecting people globally, the power to hide behind anonymous platforms has also equipped many with the ability to spread hate online. Our project analyzes such hate comments written by Japanese and American audiences to gain insights into the sociocultural factors that shape the nature of online hostility. We chose four celebrities: one American female, one American male, one Japanese female, and one Japanese male, and used multiple social media platforms to collect a total of 120 comments. Upon categorizing these comments by type, tone, and directness, we found that there are no significant differences between comments targeted towards Japanese celebrities and American celebrities. This conclusion is fascinating, as it shows that values that characterize a certain culture, such as politeness and collectivism, and the linguistic barriers they may pose were not scientifically sound when it comes to the online world.

Introduction and Background

In today’s highly technological and globalized society, social media has quickly made itself a necessity in social relationships around the world, but the power to hide behind anonymous platforms has also equipped many with the ability to spread hate online. Ranging from cancel culture to haters, online hate culture has become so integrated to our society that it has manifested itself as an interesting sociolinguistic phenomenon. It is this precise overlap between sociolinguistics and online speech around that world that we wanted to research.

Our project compares hate comments targeted towards Japanese and American celebrities as a way to gain insight into the distinct sociocultural contexts and linguistic patterns that shape the expression of online hostility. Understanding the complexities of hate speech requires an exploration of its linguistic, cultural, and sociological dimensions. By comparing hate comments written by Japanese and American audiences, we can begin to understand the variations and similarities in the ever complex issue of online hostility. Given this context, our research question then is: How are written negative comments online directed towards popular entertainment public figures similar or different between Japanese and American speakers?

Defining hate comments becomes more intricate when we consider the linguistic, cultural, and sociological differences between Japanese and Standard American English. Negative comments are extreme forms of “online incivility”, and they can be recognized and understood differently depending on various normative concepts and cultural backgrounds (Schmid et al., 2022). To establish a comprehensive framework of what is considered a “hate comment”, we will adopt the definition proposed by Alzarouni who writes, “those (online hate) directed to a person or a particular group to express intolerance for the individual or their ideology” (2022, p. 5). Japan’s culture emphasizes hierarchy, group harmony, and politeness which translates into a high language positionality and indirect speaking style. However, American culture promotes individualism which is expressed in the way Americans speak, such as the lack of structured high language and freedom to discuss social taboos. Additionally, resistance towards progressive ideas may be observed due to Japan’s more conservative socio-political structure (Feldman, 2023). Given the contrast in these two societies, we hypothesized that Japanese hate comments would center around comments that came as a result of maintaining the national status quo, such as promoting standardized beauty norms and criticizing mannerisms, whereas American hate comments would directly criticize celebrities based on the hater’s individual moral code rather than as a result of social constraints.

Methods

Establishing a way to test this hypothesis meant that we needed to test the frequency of our linguistic variables within a controlled environment. That being said, we collected 120 hate comments on Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram directed towards Japanese and American celebrities across 4 categories. These four categories test the correlation and frequency of hate between gender and race: Japanese male, Japanese female, American male, and American female. In order to find hate comments for these 4 categories, we collected online hate directed to our representative celebrities, Kuro-chan, Ryuchell, Timothée Chalamet, and Demi Lovato.

We collected this data by choosing the 30 most interacted hate comments made in 2023 under social media posts made in the same year from the celebrities’ personal social accounts. Only comments written in Japanese and made by Japanese speakers were analyzed for our Japanese celebrities; conversely, only comments written in American English were analyzed for our American celebrities. From these 120 comments, we then analyzed frequency across three linguistic variables: type of identifiable hate, tonality, and toxicity. By identifiable hate, we wanted to categorize the hate comment in regards to what it directly criticized which we classified into 6 groups: appearance, gender identity/sexuality, private affairs, personal hatred, mockery, and violence. It is important to note that hate comments were not restricted to one category, rather they could be categorized under multiple if they fit the requirements. An example of this would be a comment made to Demi Lovato, “It’s the chin for me. 🤪” which was classified as both mockery and an appearance hating comment. In order to analyze tonality, comments could also be categorized into 4 major tonal groups: serious, comedic, pitiful, or neutral. Lastly, the variable of ‘toxicity’ stems from existing previous research conducted by Won Ik Cho and Jihyun Moon on Korean online hate comments. Cho and Moon define toxicity as 1) dependent on how hateful the speech is, and 2) its ability to influence either the victim or other commenters (2021, p. 4-5). In order to gauge toxicity, we adapted this concept to instead analyze the “directness/indirectness” of the hate comments. An example of an indirect comment would be, “lowk basic but ok” which was directed to Timothée Chalamet vs. a direct comment “気持ち悪いから目覚めんな🤢🤢🤢” (“I hope you never wake up because you are disgusting”) directed towards Kuro-chan. Through this methodology, our main goal was to count and compare the frequency of these different linguistic markers and see if there were any differences, similarities, or correlations across Japanese and American hate comments, and subsequently, global hate culture.

As a disclaimer, we wanted to acknowledge some expected fluctuations in types of online hate for each of our categories. At first, we aimed to pick noncontroversial, nationally, but not internationally, acclaimed celebrities of each country with approximately similar fame in each nation in order to minimize data alteration of any kind. However, this proved to be difficult as we were unable to find hate comments directed to popular Japanese male and female celebrities. The only hate comments we could find were made to already “controversial” Japanese celebrities. Kuro-chan is problematic for his online comedic persona which is perverted, misogynistic, and violent in nature. Ryuchell is scrutinized by the Japanese public for being a transgender woman. Given these factors, we assumed our data would be skewed and expected higher rates of violent comments directed towards Kuro-chan and more hate comments regarding gender identity directed towards Ryuchell. We also expected a higher rate of gender and sexuality hate comments directed towards Demi Lovato as well, as they are bisexual and nonbinary (she/they pronouns). Our predictions were proved partly true as our data reflects that only Ryuchell and Demi received comments in regards to their sexuality or gender identity, while neither Kuro-chan and Timothée received comments of that nature. However, the hate comments were still dispersed across several different categories.

Findings

Context

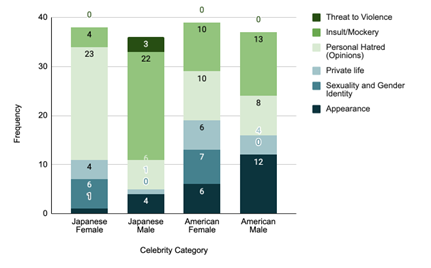

The data obtained from the context categories revealed both cross-cultural and cross-gender differences among the four celebrities. There were a few distinct findings we did not anticipate prior to the data collection, such as the high count of personal hatred comments toward the Japanese female celebrity as seen in Figure 1. This may come as a result of a widely disputed scandal Ryuchell was involved in last year. Yet, the discrepancy between Ryuchell and the Japanese male celebrity is still extremely wide. Timothée similarly was involved in controversy due to his dating rumors[1], but the comparable count of personal hatred comments to the American female celebrity may indicate that Japanese commenters are more harsh than Americans to controversial celebrities.

Other data that stands out in Figure 1 is the large count of insult/mockery comments targeted at the Japanese male celebrity. Again, we see a similar trend where there is a significant discrepancy between genders, rather than cross-culturally, in Japan and America. This can be explained by the general social media culture in Japan where trolling is considered a common and entertaining form of online conversation (Kaigo, 2017). Although internet trolling is seen in American online platforms as well, Japanese entertainment and comedy often involve dark humour. Another aspect of Japanese humor we see in comments and in many social conversations is “ohghiri” (大喜利), which are unique jokes that involved comedic takes on seemingly neutral or one-dimensional topics. Therefore, the combination of dark humor and ohghiri are commonly seen as a tactic of online trolling in Japan; especially when taking into account that the chosen Japanese male celebrity is a comedian, his haters may be influenced to convey their sentiments in a similar manner, perhaps as a way to mock his occupation.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, our data showed that American celebrities received more appearance-related comments compared to their Japanese counterparts, with the aggregate count being 18 and 5, respectively. Additionally, appearance-related comments were more common for male celebrities compared to their female counterparts – almost 4 times as much for Japan, and twice as much for America. The discrepancy between genders may be attributed to the notion that commenting on a man’s appearance is less of a social taboo than commenting on a woman’s appearance. Since oftentimes women are subjects of strict beauty standards, perhaps this discourages individuals from criticizing women based on their appearance. Particularly for Timothée Chalamet, his occupation as an actor increases the frequency of hate comments regarding this appearance as attractiveness plays a significant role in his promotional activities.

Another finding that defied our hypothesis was that there were an equal number of hate comments targeting sexuality and gender identity for both Japanese celebrities and American celebrities. As we anticipated, such hate comments were exclusively directed at the female celebrities who were both members of the LGBTQ+ community. However, we assumed that a conservative society like Japan would avoid discussing topics relating to sexuality, while American progressivism meant that we expected Demi Lovato’s hate comments to be primarily about her sexuality. Surprisingly, we saw almost equal amounts of hate comments about sexuality and gender identity, where a Japanese female celebrity received 6 and the American counterpart received 7. This may be because social media permits anonymity which in turn allows commenters to code-switch and not adhere to their expected linguistic social restrictions. Japanese commenters, therefore, may feel less obligated to uphold social harmony online and express underlying opinions they would not say otherwise. Additionally, the nature of online platforms transcends cultural boundaries. The “international” online community lacks rigid cultural norms or taboos that regulate how certain topics should be treated or discussed. Therefore, Japanese commenters may be code-switching into the ‘online language’ or culture that allows them to engage in conversations that might be considered taboo in Japan.

Tone

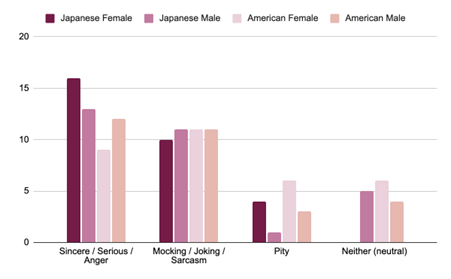

When looking at tonality, our results show that Japanese female celebrities received the most ‘serious’ tone comments. There were no drastic differences between Japan and America when looking at tonality, excluding the pity tonality. We expected for there to be a higher rate of pity-toned comments for Japanese celebrities than for American celebrities due to Japanese culture which emphasizes politeness and humility. However, contrary to our predictions, there were more pity-toned comments for Americans overall. This may be due to the ability to be vulnerable in America, where influencers and celebrities are often encouraged to be transparent to their audience. As American celebrities tend to appeal to the masses by relating to their humanity, when celebrities face setbacks they are in turn treated with the same humanity and pity.

Another explanation for the pity tonality could be the presence of negative politeness in American online culture, as many of the pity comments we counted displayed negative politeness. Commenters at times used indirect speech to display their discontent. By framing it as a suggestion rather than a comment, the hater aimed to preserve the other person’s autonomy and avoid sounding too forceful. We think individuals in America rely on negative politeness strategies to express their criticism and avoid confrontation due to “cancel culture”.

Toxicity/Directness

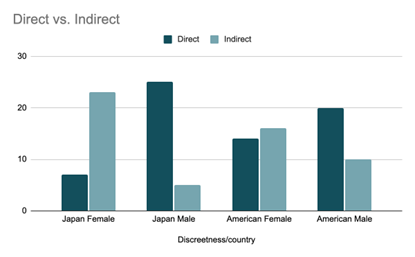

In regards to toxicity, or directness as we refer to it in our study, we originally expected Japanese comments to be primarily indirect whereas American comments to be direct. This is based upon Japan’s high language and how it tends to place a greater emphasis on respect, politeness, and conformity, which in turn discourages individuals from expressing explicit or controversial opinions openly. In contrast, American culture generally emphasizes freedom of expression and individualism, which may lead to more direct comments being shared online. However, our results show that there was no particular pattern cross-culturally, but that a correlation did exist between genders. Overall, male celebrities tended to receive more direct comments than their female counterparts as displayed by our data.

We think that due to gender roles in both countries and views on women in Japan as submissive, they had more implicit comments. Also, it could be considered taboo to comment on a woman’s appearance directly since it can contribute to this objectification and reinforce harmful gender stereotypes. Society holds women to different standards than men when it comes to appearance and behavior and implicit comments could be used to imply those notions. Regarding the more explicit comments for Japanese male celebrities, Japanese fan culture could cause a certain devotion and obsession that can sometimes lead to more explicit or possessive comments being directed towards male celebrities.

Future Research

Due to this study’s time constraints, we cannot be certain of this idea, but a proposal for future research to test this would be to increase the sample size by collecting thousands of hate comments made to multiple celebrities within our four categories. Frequency of hate comments and their types should then be categorized and compared between not only Japan and America, but other countries around the world as well. Additionally, our findings showed that there was a stronger correlation between hate comments and gender vs. hate comments and race; thus, analyzing hate comments in accordance to both the gender of the commenter and the gender of the celebrity would also be interesting. Applying the concept of toxicity will provide insight as to whether or not speech tends to be harsher or softer when criticizing individuals of the same gender identity.

Conclusion

Ultimately, our findings showed that when categorized into types of identifiable hate, tonality, and toxicity, hate comments made by Japanese and American English speakers did not differ significantly from each other. This conclusion in particular is fascinating as it shows that the preconceived notions we had about polite vs. impolite society and linguistic barriers they may pose were not scientifically sound. In fact, it instead points that perhaps the online world may be a liminal space where culture, language, age, gender, and other sociolinguistic factors are broken down, creating instead a universal shared language and culture.

References

Alzarouni, E. (2022). Detection of Hateful Comments on Social Media Detection of Hateful Comments on Social Media. Rochester Institute of Technology. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=12308&context=theses

Cho, W. I., & Moon, J. (2021). How does the hate speech corpus concern sociolinguistic discussions? A case study on Korean online news comments. ACL Anthology. https://aclanthology.org/2021.nlp4dh-1.3/

Feldman, O. (2023). Challenging Etiquette: Insults, Sarcasm, and Irony in Japanese Politicians’ Discourse. 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0467-9_5

Kaigo, M. (2017). The Japanese Internet Environment. Social Media and Civil Society in Japan, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5095-4_1

Schmid, U. K., Kümpel, A. S., & Rieger, D. (2022). How social media users perceive different forms of online hate speech: A qualitative multi-method study. New Media & Society, 146144482210911. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221091185