Jamie Seals, Makena Larson, Betsy Benavides, Faith McCormick

When looking at the work previously done on the intersection of white fragility and sociolinguistics, we noticed a gap in research that we wanted to fill. We conducted interviews between two white peers, the topic of conversation being sensitive topics such as race and racism. We hypothesized that the interviewees would take a neutral stance when speaking on the subject of race. We looked specifically at word choice, stance, and circumlocution. Using conversation analysis on all three interviews conducted, we were able to look at these linguistic elements and draw conclusions. It was found that interviewees used circumlocution, hedged and hummed, and all held a very particular stance. In our article, we delve more deeply into what we found, the examples of conversation analysis, and what the most significant takeaways were.

Introduction

For our project, we wanted to take a sociolinguistic approach to look at white fragility and discussions pertaining to sensitive topics. We looked specifically at how white people respond to questions regarding race and racism. When looking at previous work examining the intersection of white fragility and sociolinguistics, we found a lack of research that we wanted to supplement and deepen. We wanted to look at white fragility by conducting interviews with two white peers regarding race, which we could not find had ever been done. Previous research done by Robert DiAngelo, highlighted a discomfort that white people had when dealing with issues of race, “a single required multicultural education course taken in college, or required “cultural competency training” in their workplace, is the only time they may encounter a direct and sustained challenge to their racial understandings.” (DiAngelo, 2011). DiAngelo’s, along with others’ work done on white fragility, led us to our final decision on the aspects of our interviews. We conducted interviews between two white peers, both of which were twenty to twenty-two years old. We wanted to analyze these interviews specifically through a sociolinguistic lens, which makes our research unique. Our research is necessary because, by better understanding how white people feel regarding race and discussions about it, we can start to break down walls between one another and have more open conversations. These discussions allow for transparency and a sense of stronger community values within the UCLA culture and in our greater society. Furthermore, we believe that conversation is very important which is why we looked at it in depth. We did conversation analysis on our three interviews and examined them by looking at circumlocution, word choice, and stance. We hypothesized that all the participants would take a neutral stance, and we found this to be accurate but much more nuanced than we had expected.

Methodology and Results

After careful thought and consideration throughout our experiment, we found that within our three interviews it was vital to keep in mind what key linguistic features we were searching for when conducting the research portion of our project. Having both the interviewer and the interviewee identifying as white, we hoped this environment would create a sense of comfort within the conversation. We also reassured the individuals that this was a safe space to speak freely and reflect on what they have personally experienced here at UCLA. After analyzing the recordings of each interview and uploading the conversations through Trint, a transcription processing application, we were able to effectively observe the outcome of our data and look at the speech and language patterns between the two speakers. Our first finding from the interviews was how there was still an obvious level of uncomfortability between the interviewer and interviewee when asking the questions. For example, in the second interview, the interviewee is asked the question, “do you think racism exists in UCLA culture or on campus?” The interviewee responds by saying, “yes, but it’s not like I’ve seen it directly.” This response is important to our study because it proves how students here are aware that here on campus there are individuals experiencing racism. However, they quickly reassure us that they are not involved or a part of the problem at hand. Throughout the interviews, we also noticed how, when asking the question, “Do you think UCLA is inclusive to all students?” The individuals were swift to respond and say no. However when asked if they believe racism exists on campus or in the culture here at UCLA, they take more time and reply hesitantly with “yes, Uhm, probably” (Interview 2). This longer pause can signal that the interviewee could be slightly caught off guard or uncomfortable answering the question, in fear of giving the wrong response. Secondly, we found that in our third interview, when the individual was asked about racism at UCLA, they responded with, “I heard from the grapevine that….” This immediately personifies to the interviewer that the individual wants to be excluded from the information they are about to share. The interviewer does this in a way to agree that, yes, there is exclusion here on campus happening but wants to ensure she is not accounted for in that statement. This is critical for our study because it helps us reveal how quick students are to agree there is blatant inequality here at UCLA, but in a way, they would like to acknowledge it is problematic but are quick to cover themselves before even pressing more into the issue. The second interviewee, at the opening of the conversation, also expressed their feelings on how they felt about these questions. When asked if they think UCLA is inclusive to all students, they respond with, “uh, this is not a fun topic to talk about” in the recording, the student pauses and then nervously laughs while saying this is not a fun topic to talk about. The nervous laugh along with them voicing how this is not a fun topic to talk about, are both powerful indicators the individual was hesitant to talk on this subject without feeling uncomfortable. We must circle back to our hypothesis stating these students would take a neutral stance. It is clear from our findings that our pool of participants remained completely neutral throughout the interview. All three students agreed they benefited from white privilege at UCLA, however when being asked these questions about race, we found they all displayed levels of discomfort and attempted to sever themselves from any racist or discriminatory acts people might be experiencing or hearing about in UCLA culture or campus.

Discussion

Although all three interviewees had different responses to the questions, we found a few patterns across the three. Upon answering each question, interviewees would often find ways to distance themselves from the issue. From saying things like “I’ve heard”, “Actually, I can’t really think of an example, so maybe not” or “Yes, but it’s not like I’ve seen it directly.” This is what sociologist Caprice Hollins describes as the individual approach White individuals often use when speaking about race. Individuals may find ways to maintain a positive self-image by pushing away their closeness to these issues or moving around the topic of conversation (2020, Hollis). To add onto this, something we picked up on was the interviewees avoidance using racialized language, instead opting for terms like “minorities” or “different race” instead. This is what is described as aversive racism, or racism that is manifested in subtle ways (Diangelo, 2018, p.59). Furthermore, they never directly state their opinion on some of the questions, often finding a sort of a neutral position or a middle ground. This type of stance is known as a form of White solidarity, where individuals in conversation will often build on this idea of a “common stance” regarding race-related issues. These stances rely on both silence on racial matters and a subconscious implied unity between parties to uphold this solidarity (DiAngelo, 2018, p.72). When all three of the interviewees used this back and forth, yes and no response, it is possible that they are not able to navigate that common ground which could lead to some of the discomfort demonstrated.

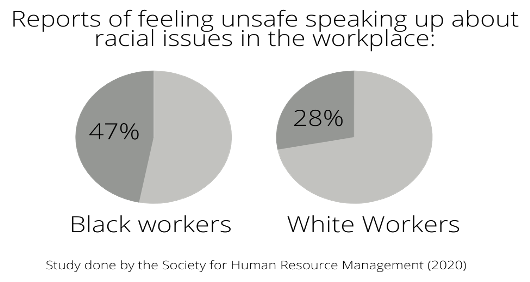

After conducting our study, most of what we saw fell in line with what sociologists are saying about conversations on race, however it does not match some of the quantitative data we found. The stances we picked up on during the interview were things we expected but did not expect to find clear discomfort. This is what prompted us to look into other research where we found that White individuals feel significantly less discomfort speaking about these topics compared to Black individuals. The following Figure 1 is demonstrative of a 2020 study done by the Society for Human Resource Management which collected data from 1,275 participants about their workplace environment. While our study focuses on universities, we feel that the study on the workplace environment is still relevant to our topic. The study found that 47% of Black respondents do not feel safe speaking out about issues of racial justice compared to 28% of White respondents who said they do not feel safe for the same reason (2020, p.11). There can be many reasons for this discrepancy. While this data could indicate that our 3 interviewees happened to be a part of the 28% of people who feel uncomfortable, it’s also possible that the perception of themselves is different than the way others (us interviewers) perceive them. If given the opportunity, we would have a second round of interviews where we would ask not only about racial issues but also how individuals feel about speaking on racial issues.

Observing our results and how they fit into a broader context, racial issues and racial justice has always been prevalent, deeply and radically well-established, and formed in society. UCLA represents its own subcategory of society, as a community. By theoretical implications, these findings we provided show to be significant in spaces of policy, practice, and further research. Additions are also made to the existing discussion of race and social inequalities related to. By practical applications, it presents how we can better self-reflect and ask ourselves: if certain conditions were fulfilled, not only for the student body but beyond that. Our findings can be extended to other situations, such as friend groups, educational spaces, relatives, and workplaces. Anywhere we find a place of interaction and community, this study could be applicable. Our findings help us understand a broader topic of the foundations of human interaction. With continued conversations regarding social injustice, we are better equipped to integrate our worldviews, as well as comprehend and be attentive to that of others. We can improve and create equitability for all, resulting in better representation, accountability, uplifting underrepresented groups, and improving the overall well-being of one another.

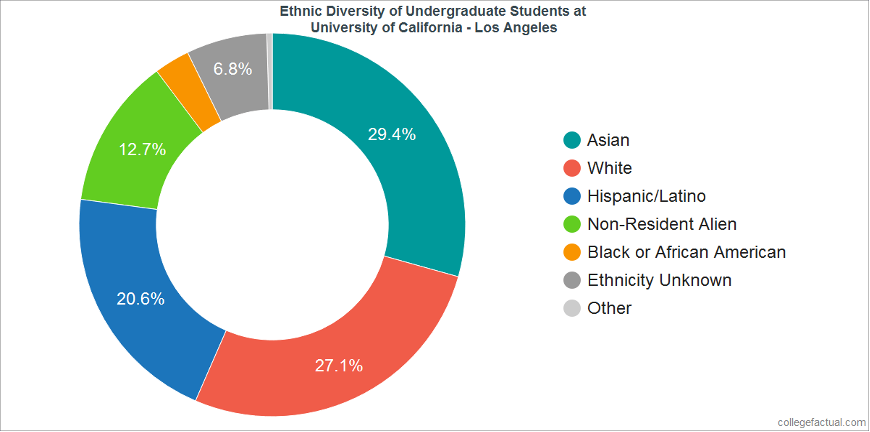

As seen below, a chart of the ethnic diversity of undergraduate students at UCLA. An article was written at Penn State in 2018 by the Diversity group in response to College Factual’s ranking of UCLA’s diversity and ethnicity. The article aimed at identifying and examining how diverse of an institution UCLA is. We found this article written at Penn State to be extremely critical and relevant to our work because it perfectly analyzes the exact breakdown of each ethnicity present on campus at UCLA. From this data in the chart, we are allowed the opportunity to more effectively determine the disproportions or inequalities that may be prevalent based just on the percentages of various ethnicities here at UCLA As seen in the chart, carefully note how the orange percentage of the chart is not even listed and exact percentage. In this chart the color that represents individuals of black or African American ethnicity accounts for less than 4% or the entire student body. This statistic is crucial to the argument we pose in our experiment because the percentage of African American and black individuals is disproportionately represented on campus here at UCLA, while the percentage of white or Caucasian presence on campus stands at 27.1% the second to highest percentage of all ethnicities listed.

References

DiAngelo, Robin (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3(3):54–70.

DiAngelo, D. R. (2018). White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press.

Diversity at UCLA – Diversity. (2018, March 8). Sites at Penn State. Retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://sites.psu.edu/pasternakcivic/2018/03/08/diversity-at-ucla/

Hollis, C. (2020). What white people can do to move race conversations forward. Youtube.com. Retrieved 6 7, 2022, from https://youtu.be/7iknxhxEn1o

Society for Human Resource Management. (2020). Together Forward. The Journey to Equity and Inclusion. Retrieved 6 5, 2022, from https://shrmtogether.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20-1412_TFAW_Report_RND7_Pages.pdf