Talar Anoushian, Kimberly Gaona, Kimberly Maynard, Ann Mayor, and Guoran Zhang

Communication within couples can be difficult at times, but is it different when they’re bilingual? This study aims to clarify any breakdowns in communication within bilingual couples when it comes to speaking to their less proficient language for a long period of time. The data used for this study was collected from YouTube challenge videos titled “Speaking to My Partner Only in Korean for 24 Hours”. The challenge goes as follows: the most proficient partner would speak in the challenged language, Korean, and the other partner would try to understand and respond to the conversation as much as possible. The two bilingual couples that were used for this study vary in Korean proficiency — one couple being intermediate and the other beginner. During the study, we found some patterns linking certain strategies for repairing communication to the varying levels of proficiency, meaning some strategies are more likely to be employed during bilingual communication when one of the speakers is less fluent. We also found some examples of how the nature of these couples’ relationship influenced how they approached certain communication breakdowns and their partner’s differing proficiency level.

Introduction & Background

Many of us have seen the popular videos where a bilingual speaker chooses to speak only their native language for 24 hours, much to the confusion of those around them who may not be as fluent. This challenge became especially popular amongst bilingual couples with different language backgrounds. Not only do these videos provide an entertaining viewing experience, but they also allow us insight into how bilingual couples communicate in their various languages and what they do when communication breaks down. We decided to use these videos to see how the strategies used to mend miscommunications differ between a couple where both speakers are fluent in the language being spoken and a couple where only one speaker is fluent in the spoken language. We are especially interested to see how they will choose to mend these misunderstandings when the option to switch into their shared language (the language they both speak most commonly) is taken away from them.

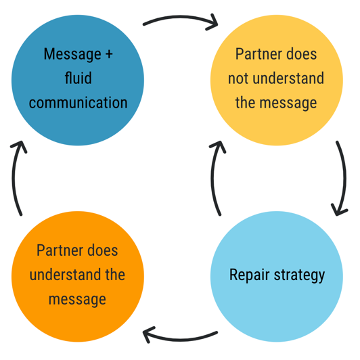

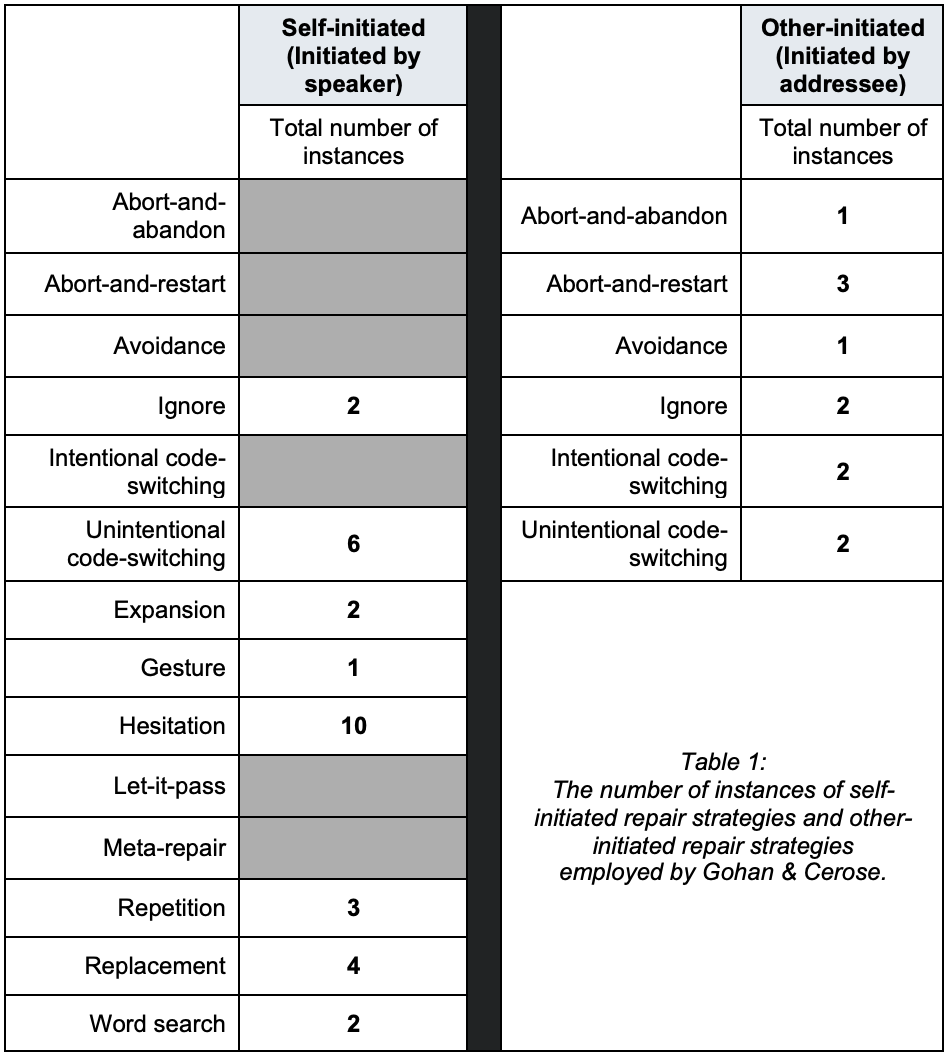

We decided to study Korean-English bilingual couples — more specifically, couples in which one partner is a native Korean speaker and the other varies in Korean proficiency. Recent studies have shown that the number of bilingual individuals has progressively increased in the past years, and this is especially true for South Koreans. For South Koreans, having the flexibility to use their native Korean language proficiency as well as advanced English language proficiency gives these bilingual speakers an advantageous position in society (Choi, 2018). While their communication skills may seem advanced, bilingual speakers still run into errors and misunderstandings in their communication, and they use different methods to solve these. These methods used to resolve miscommunication are known as “repair strategies.” We developed a list of these strategies from various other studies and grouped them into two categories: self-initiated and other-initiated. The full list of the strategies along with their definitions (and the definitions of self-initiated and other-initiated) can be found in Table 5 in the Appendix. The way these strategies can come into play during conversation is illustrated in the image below:

As shown in Image 1, the cycle of communication is as follows: two interlocutors are talking and a message is being communicated, then at some point, the addressee doesn’t understand what is expressed. Thus, the speaker uses a repair strategy in hopes of getting their intended message across. Sometimes, even after a repair strategy is used, the addressee still doesn’t understand what is being expressed, then the pattern repeats until the partner does understand the message. Once the message is successfully communicated, fluid communication continues.

To build our subject pool, we focused on the following popular Korean-English bilingual couples: Gohan and Cerose who share a YouTube channel named Jin & Juice, and Jin and Hattie Green who share an eponymously-named Youtube channel. Gohan and Jin are South Korean native men speakers, but their partners are non-native Korean speakers. Cerose of Jin & Juice is an American woman who learned Korean as she lived in South Korea, and she gradually acquired a native-like command of the language. Hattie is a British woman who lives with her partner in South Korea as well, and as a result she learned some basic Korean but speaks at a beginner level proficiency. Since each of these couples have a less fluent partner with varying levels of proficiency in Korean, we expected different strategies to be employed by each couple throughout the challenge. Since some strategies don’t involve an advanced level of Korean — like abort-and-abandon and avoidance — we expected the couple with only one fluent speaker to use these simpler repair strategies. On the other hand, other repair strategies like expansion and meta-repair require better understanding of Korean, so we expected the couple with two fluent speakers to use these and similar self-initiated strategies. However, we can’t definitively say which couple will code-switch from Korean to English, but we do anticipate that code-switching will be used mostly by the couple where only one speaker is fluent, because there would be no way to simplify what is said so that their partner can understand while still speaking Korean.

Methods

First, we collected data from the channels mentioned above performing the “Speaking to My Partner in Only Korean for 24 Hours” challenge. Below are the links to their respective channels:

Although we originally intended to study 3 different bilingual couples — Gohan and Cerose from the YouTube channel Jin & Juice, Dong-In and Farina from the YouTube channel Farina Jo, and JinWoo and Hattie from the channel Jin and Hattie — we realized that, as we began to collect data, Dong-In and Farina did not fit the specifications we had set forth for our subject pool. Dong-In and Farina are less of a Korean-English couple and more like a Korean-German couple since they use German more frequently in their everyday lives. Because of this, they were no longer good candidates for this study so we decided to remove them from our subject pool.

For our research, we used a similar method to Belgrimet’s (2020) study of bilingual students and their use of repair strategies in communication breakdowns. We looked specifically for moments where the communication breaks down to see what strategies are employed when code-switching is supposed to be avoided. We also looked for moments where a couple failed the challenge by using code-switching as a repair strategy. These repair strategies will be categorized using a defined list from various sources, and it can be found in the Appendix. To study Gohan and Cerose, we decided to watch their video “Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours.” To study Jin and Hattie, we decided to watch their video “[AMWF] Speaking Korean To My Girlfriend for 24 hours ver.2 * she has no idea * | Calling Noona!?.”

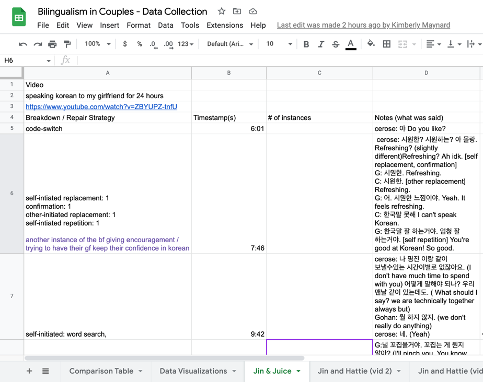

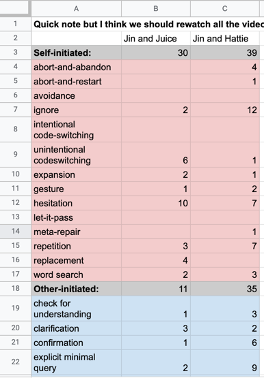

The different strategies used from each Korean-English couple will be compared to see any noticeable differences in their rate of usage. In order to perform this comparison, once all the strategies used by each couple have been counted, the data was inputted into a table to allow for easier side-by-side comparison. We also noted the function of the various strategies in an attempt to explain the reasons behind why certain strategies are more likely to be used in one context than another. In addition, we looked at intentional code-switching moments separately and, using our knowledge of code-switching and other repair strategies, drew some conclusions to explain why the speaker felt a need to code-switch instead of using a different strategy to repair the miscommunication. Below are examples of spreadsheets we created to tabulate our data and notes:

Results and Data Analysis

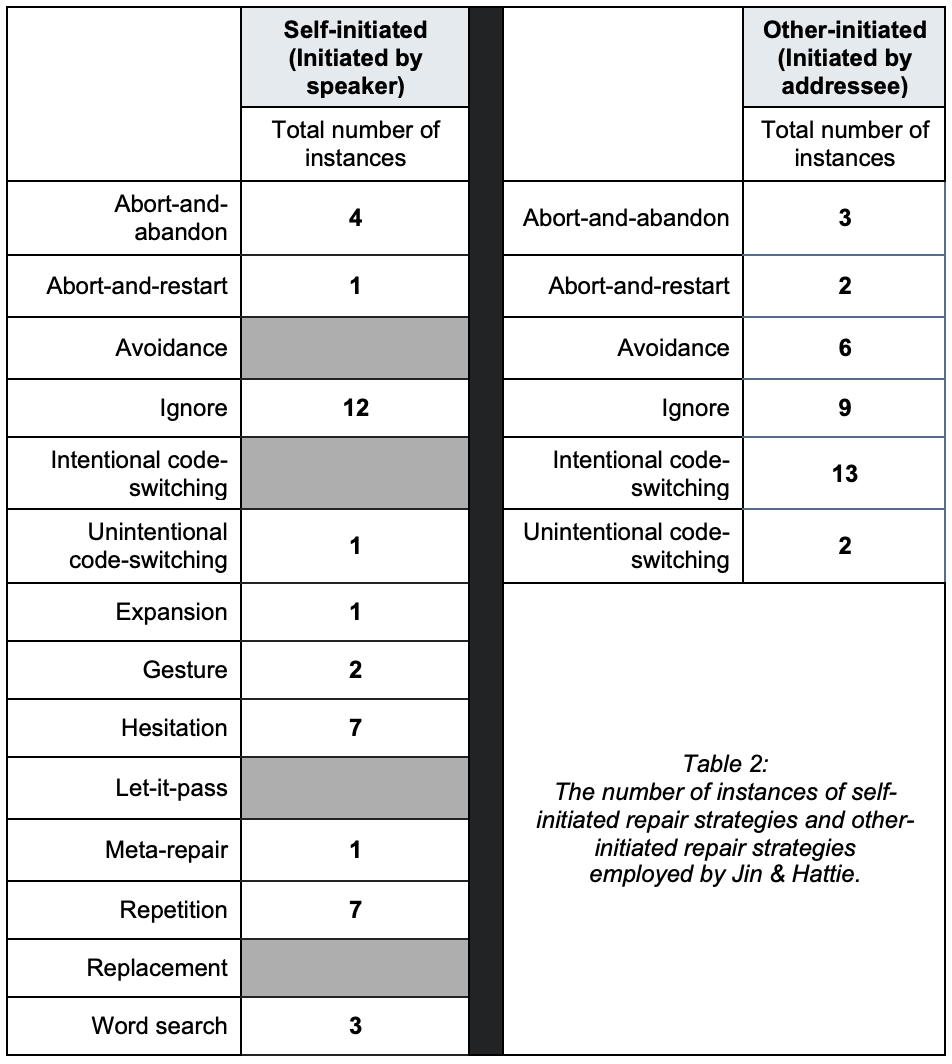

For the first couple, Jin and Juice (aka Gohan and Cerose) which contained two fluent speakers, we looked at their video “Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours.” They used some of the strategies we discussed before, as seen in the table below.

For them, the most commonly used self-initiated strategy was hesitation. Most instances of hesitation were seen when Cerose was speaking Korean. For example, we have this instance from when she was applying lotion on Gohan’s face and explaining how she has been doing his skin-care for him:

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 5:03) Cer: 요즘 명진이 피부가 너무. . . Lately Gohan’s skin is very. . . Goh: 쓰래기라? Trash? Cer: 응 너무 안 좋아서. . . 피부 관리. . 시키는거야 Yeah it’s not very good so... I’m doing... his skin care for him

Each “. . .” is a moment where she pauses or hesitates. The first one we actually classified as an example of “word search,” since Gohan fills in the next part of the sentence for her, but the next two are moments we labeled as “hesitation.” In this case, the hesitation seems to not only be due to her having to think of what to say in Korean, but also the fact that she is multitasking and applying lotion on Gohan’s face at the same time.

We also saw quite a few instances of unintentional code-switching in this couple. A couple of examples from Gohan include:

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 2:35) Goh: 내가 요즘 유튜브에서 요리 tutorial 듣고 있는데... *gasp* 개물어 I've been watching a lot of youtube cooking tutorials lately… *gasp* bite me

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 5:16) Goh: 여기 여기 *crevices*에도 해줘. Here, here get the crevices too.

We had expected that as the more fluent couple, they would be less likely to fail the challenge and code-switch since they would struggle less to communicate in Korean. Instead, we saw multiple instances of code-switching, but they were all unintentional like the ones above: not being used to resolve a misunderstanding but rather naturally coming out as they spoke.

When it came to the other-initiated strategies, there was no clear outlier in the data and they were all used pretty evenly. The strategy that was used the most was clarification, but not all instances of clarification were used to resolve miscommunication caused by the language gap. Sometimes it would be used simply to keep the flow of a conversation or just confirm information, similar to what we would see in monolingual conversations. For example:

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 2:32) Cer: 배고파. I'm hungry Goh: 배고픔? You're hungry? Cer: 응 Yeah

The next couple, Jin and Hattie, is the couple that has one Korean native speaker, Jin, and one beginner-level speaker, Hattie. Overall, this couple had far more communication breakdowns as Hattie could not understand most of what was said by Jin, which in turn led to a more frequent use of repair strategies. The numbers can be seen in the following table.

In this couple’s interactions we see a large amount of “ignore” happening. There were many moments in which Hattie could not understand what Jin was saying when he spoke Korean so rather than attempt to fix the situation she would simply act as if she had not heard what he said. Below is one instance in the video where we see a lot of ignoring on Hattie’s side as well as a lot of repetition on Jin’s side:

[AMWF] Speaking Korean To My Girlfriend for 24 hours ver.2 * she has no idea * | Calling Noona!? (Timestamp: 1:31) Jin: 아니 장미 맞아 No you're right this is a rose Hat: That's a really big rose. That can't be a rose. Jin: 이거 장미 맞아 This is a rose. Hat:I should take a picture for my step mum. She would love these. Jin: 응.. 아니 이거 장미 맞다고 Yeah.. But I said you're right this is a rose. Hat: What? Jin: 장미 맞다고 이거 I said this is a rose Hat: It's quite hot and sunny Jin: 아니 너 왜 자꾸 다른 말 해? 내가 한국말 하는데 Why do you keep changing the subject? I'm speaking Korean…

The first two times Jin tries to tell her she is right about it being a rose she doesn’t even look at him and continues talking to herself about whether or not it is a rose and how she should take pictures for her mother, giving us two instances of “ignore.” The third time, she does acknowledge that he is speaking to her and asks “What?” an example of “explicit-minimal query,” but after he repeats himself for the third time she goes back to ignoring him and changes the topic to the weather.

We noticed that in both couples there were instances of the native speakers using purposeful word-choice to make things easier for their partner to understand. For example, in Jin and Hattie’s video, there is one case where Jin uses a “Konglish” word, or a Korean word borrowed from English, as well as a time where he references a line from a drama that Hattie would be familiar with:

Konglish example: [AMWF] Speaking Korean To My Girlfriend for 24 hours ver.2 * she has no idea * | Calling Noona!? (Timestamp: 4:31) Jin: 나 이거 스킴해볼까? Should I try skimming this? Hat: You're skimming rocks? We did skim rocks

Drama Reference Example: [AMWF] Speaking Korean To My Girlfriend for 24 hours ver.2 * she has no idea * | Calling Noona!? (Timestamp: 1:51) Jin: 나는!! I am!!! [reference from drama Itaewon Class] Hat: 나는 박새로이 [unintelligible]. . . 감사합니다 I am Park Seroi [unintelligible]. . . Thank you

For Gohan and Cerose, we found one possible instance of this type of “simplification” of the language to make it easier for the partner to understand:

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 2:20) Cer: 몇시야? What time is it? Goh: 지금?? 6시 32분 오후.. 밤 6시다 Right now?? 6:32pm.. 6 o'clock at night

It isn’t entirely clear if this is just Gohan simply rewording how he says the utterance without any regard for her skill level, but we believe it’s possible that he purposely chose to switch from using 오후 “pm” to 밤 “night” which is a more straightforward and commonly-known word for Korean learners.

There are also times where they seemed to be trying to increase their partner’s confidence in Korean. For instance, in Jin and Hattie we see an example of Hattie gaining confidence as she understands something Jin says, and even though she clearly misunderstands what he says after he chooses not to mention this and instead acts as if she is doing well to let her maintain her confidence:

[AMWF] Speaking Korean To My Girlfriend for 24 hours ver.2 * she has no idea * | Calling Noona!? (Timestamp: 6:59) Jin: 여기 연어가 진짜 맛있어 The salmon here is really delicious Hat: It's really delicious Jin: 어떻게 알았어? How did you know? Hat: I know! I know what you're saying! It's really annoying cause I can actually understand you this time. Jin: 그럼 말해 Then say something Hat: Yes Jin: 한국어로 말해 Say something in Korean Hat: I can understand Korean. My Korean's getting better. Jin: 오호호.. [unintelligible] Ohoho [unintelligible] Hat: I can't say anything but I can understand it. Jin: Boom

We can see that when he asks her to say something in Korean, she clearly misunderstands and responds as if he is saying something else. However rather than bringing this up and making her realize that she misunderstood, he reacts with supportive responses and lets her continue to believe that she understood.

As for Jin and Juice, Gohan attempts to increase Cerose’s confidence with direct compliments such as below:

Speaking Korean to my girlfriend for 24 hours (Timestamp: 7:50) Cer: 한국말 못해 I can’t speak Korean Goh: 한국말 엄청 잘하는 거야 Your Korean is really good

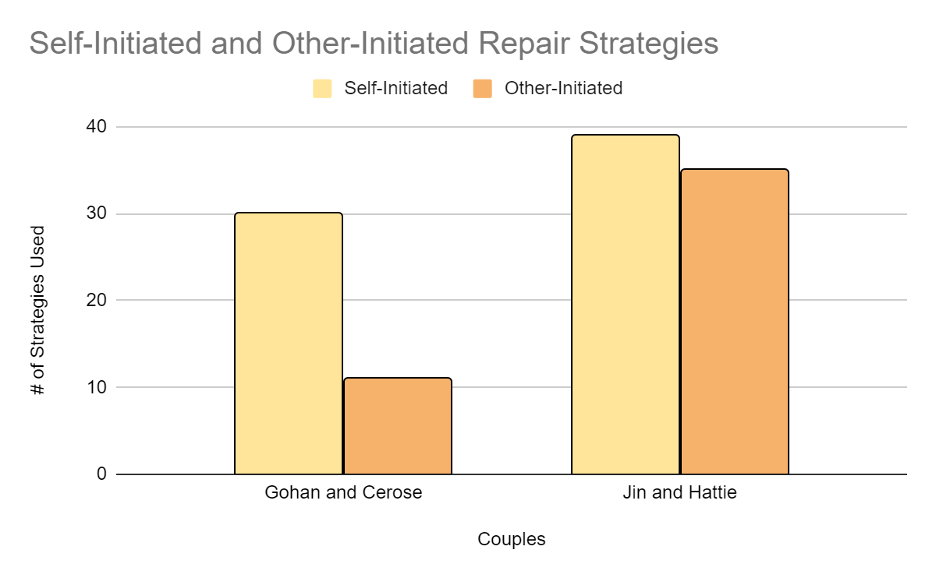

All in all, when looking at repair strategies, as we expected the less fluent couple had to use more strategies overall and did use some of the strategies we had predicted such as other-initiated repetition and ignore. We also expected that the fluent couple would use more self-initiated strategies, which was supported by our data. Both couples used a similar amount of self-initiated strategies total, but when we compare this amount relative to the amount of other-initiated strategies used, we see that Jin and Juice used self-initiated strategies far more than other-initiated strategies.

The one aspect of our data that contradicted what we were expecting was the data on code-switching. Unexpectedly, the more fluent couple, Gohan and Cerose, code-switched more than Jin and Hattie. However, we expected code-switching to be employed purposely to resolve non-understandings, which would be intentional code-switching. Since all instances we saw were unintentional code-switching, this could explain why the fluent couple was more likely to code-switch. Due to the fact that they both have good command over both Korean and English, it is likely that they code-switch more often than Jin and Hattie in their day-to-day life, thus the instances of unintentional code-switching could be explained as a result of habit.

Discussion and Conclusions

Based on the collected data, we came to the conclusion that lower fluency equals more breakdowns in communication because of the lack of understanding. Gohan and Cerose’s conversations were a little smoother due to their higher proficiency in Korean. Compared to Jin and Hattie, where Hattie was the less proficient partner, there were more breakdowns in communication. We also did find certain strategies were employed far more by the less fluent couple, indicating a link between repair strategies used and proficiency level.

In conclusion, bilingual couples can struggle in communication due to the many languages involved and their level of proficiency in each language. This study can help us understand bilingual couples and the ways they fix miscommunications while dealing with varying language proficiency. Ultimately, we can see how being bilingual does not mean that you are linguistically handicapped, and it’s rather advantageous to have access to other languages and ways to express yourself.

References

Belgrimet, S. (2020). A conversation analysis of repair strategies in communication breakdowns: A case study of algerian bilingual students. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 5(2), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijels.52.21

Choi, L. J. (2018). Legitimate bilingual competence in the making: Bilingual performance and investment of Korean-English bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(6), 1394–1409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006918791266

Cogo, A., & Pitzl, M.-L. (2016). Pre-empting and signalling non-understanding in Elf: ELT Journal, 70(3), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw015

Firth, A. (1996). The discursive accomplishment of normality: On ‘lingua franca’ english and conversation analysis. Journal of Pragmatics, 26(2), 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(96)00014-8

Gullberg, M., & McCafferty, S. G. (2008). Introduction to gesture and SLA: Toward an integrated approach. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30(02).

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263108080285

Stępkowska, A. (2021). Language choices between partners in bilingual relationships. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 21(4), 110–124.

https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2021-2104-06

West, T. (2018). A Conversation Analysis of Repair Strategies in Multilingual English Discussion Classes. New Directions in Teaching and Learning

English Discussion, 6.