Elie Barbar, Said B., Bel Jacob

It is well-known that one’s language fluency decreases the less one utilizes it. In particular, heritage speakers are a unique case in which their first language is spoken often within a familial context, yet in all other cases, it is not used. This study sets out to examine Spanish heritage speakers in the Los Angeles area to determine whether growing up solely in Los Angeles has affected their level of attrition in the Spanish language. The main hypothesis was that because Spanish is only spoken in a familial context, the speakers would have an average or below-average grasp of the language. The methods utilized to study this included a mix of surveys, tests, and interviews conducted to determine attrition rates amongst the participants. After using these methods, we found that Spanish Heritage Bilingual Young Adults in L.A. had an above-average fluency within the language, exceeding our original expectation of the participants having average or below-average levels of fluency. The main assessment from the data as to why these speakers have retained their heritage language so well is due to the environment they grow up in. Within Los Angeles, Spanish is widely spoken so not only do the participants have a chance to speak it with their family but with the outside world as well.

Introduction

Attrition and incomplete acquisition have been one of the most intriguing concepts in language development–many children grow up learning multiple languages at once, especially in densely populated areas of bilinguals, including Los Angeles. Our study goal was to discover the degree of attrition in reading and writing amongst young adults in Los Angeles. We wanted to investigate the relationship between attrition of L1 and formal education in L2. In Los Angeles, 42% of the population speaks Spanish vernacular due to it being their heritage language while being formally educated in English, which could either lead to attrition in the future or incomplete acquisition of the Spanish Language. Attrition is the loss of language over time despite fully acquiring it during youth due to multiple factors such as “emigration, extensive use of L2 in daily life” (Schmid & Köpke, 2007), while incomplete acquisition is when children deviate from the norm and were never able to fully acquire a language (Köpke, 2018). In addition, Keijzer (2008) discusses Roman Johnson’s hypothesis, stating that “forgetting a language is the reversal process of learning the same language,” which was taken into account here because we believe this depends on age – a child may acquire a language in a few years but take many more as an adult for attrition to occur.

Linguists have hypothesized in the past through the interdependent development hypothesis that learning a second language could be accelerated if one or the other is morphologically rich, which Spanish is morphologically rich. In other words, the evidence points toward children being able to acquire both English and Spanish properly (Liew, 1996). In addition, since the parents’ L1 is Spanish, it would allow the child to be exposed to Spanish properly for the first few years of life, before heavily integrating into the American society to acquire English as well. While we cannot be certain whether attrition or incomplete acquisition, previous evidence and patterns of communication of parents tend to suggest the complete acquisition of both languages, meaning that attrition is more appropriate to test here. However, there has been evidence to support that if there is somewhat of a lack of language input for the child, then incomplete acquisition may occur – in a study about bilingual English-Spanish speakers, mothers were strongly working toward maintaining their children’s Spanish abilities: “the experience of these Spanish-speaking mothers reveal that while they perceived bilingualism as important for work and family communication, they often struggled to sustain their children’s Spanish development using various home language policies and discourse strategies…several mothers reported that their child was starting to prefer English, not only with siblings and peers but also with Spanish-speaking adult caregivers” (Surrain, 2018, p. 20). This evidence suggests that formal education, as young as preschool, can play a role in L1 language attainment if parents are not providing enough input of the heritage language to the children. This could translate to attrition in college students due to the potential lack of constant input of their L1. This is why we hypothesize that due to the lack of writing and reading and strictly using L1 orally, heritage speakers will greatly suffer in competency scores since their formal education is focused on English, the dominant language. Our prediction is that test scores will be middle to low.

Methods

Participants included 13 Spanish bilingual young adults from ages 18-21. All of them were recruited in the Los Angeles area and speak LA vernacular Spanish. First, the participants filled out a survey, investigating their perceived proficiencies in speaking, listening, reading, and writing in Spanish, as well as frequencies and demographics in which they would use LA vernacular Spanish. Then, they were given a college-level written test from CLEP (College Level Examination Program). Lastly, they were offered an optional interview to explore discrepancies between their perceived proficiency and the actual test results. We analyzed their degrees of attrition and deficiency in competency in their L1, mostly in morphosyntactic structures by observing what areas of morphosyntax they tend to struggle with the most.

Results

Survey Results:

Test Results:

Interview Results:

(Linguistic Landscape)

“Living in LA I read Spanish in a lot of different places, like billboards and fliers. It’s not everywhere in LA but I see it.”

“My parents and I try to keep up on our Spanish. We agree that we will exclusively speak it at home. And when we go to the market and places like that, we see it all over the place.”

“I never really took a Spanish class, but I see it when I am out in town or when I go to Mexican grocery stores. It’s not complicated stuff but I see it written and I read it.”

( Attrition / Dominant L2)

“I took some Spanish in high school because it was required, but I don’t read it often and I don’t write it ever. It’s mostly just speaking it at home.”

“I only really speak it at home with my parents, but other than that I don’t use it often.”

(Dialect and Prescriptivism)

“This kind of Spanish isn’t exactly the type of Spanish I use, it seems like this is more like Spain Spanish.”

Analysis

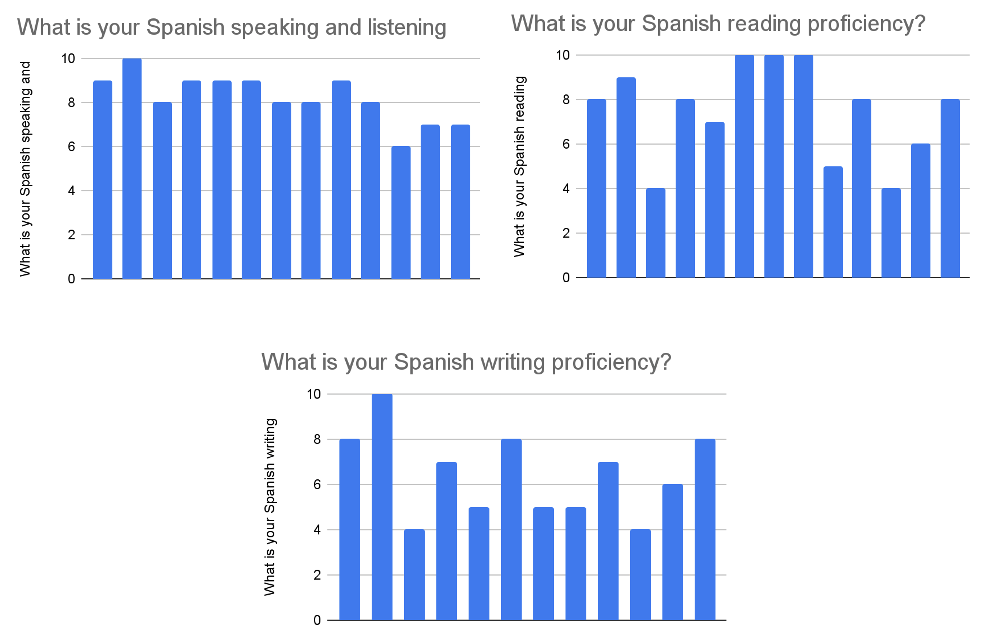

When observing the figures in the proficiency portion of the survey, our participants were fairly confident in their abilities as well-rounded bilinguals. There is a common consensus that the more someone speaks a language, the more comfortable they will become speaking the language. The average proficiencies were well above our predicted levels, as we predicted a steeper drop in the confidence in reading and writing. This goes against our hypothesis that predicted that formal education would have a significant effect on proficiency levels in reading and writing. There was a significant drop in confidence in relation to the participant’s confidence in their writing ability which does go in the direction of what we expected, just not by the amounts that were projected. One should keep in mind that the group is a mix of heritage speakers with and without formal Spanish education. This may have an impact on the data.

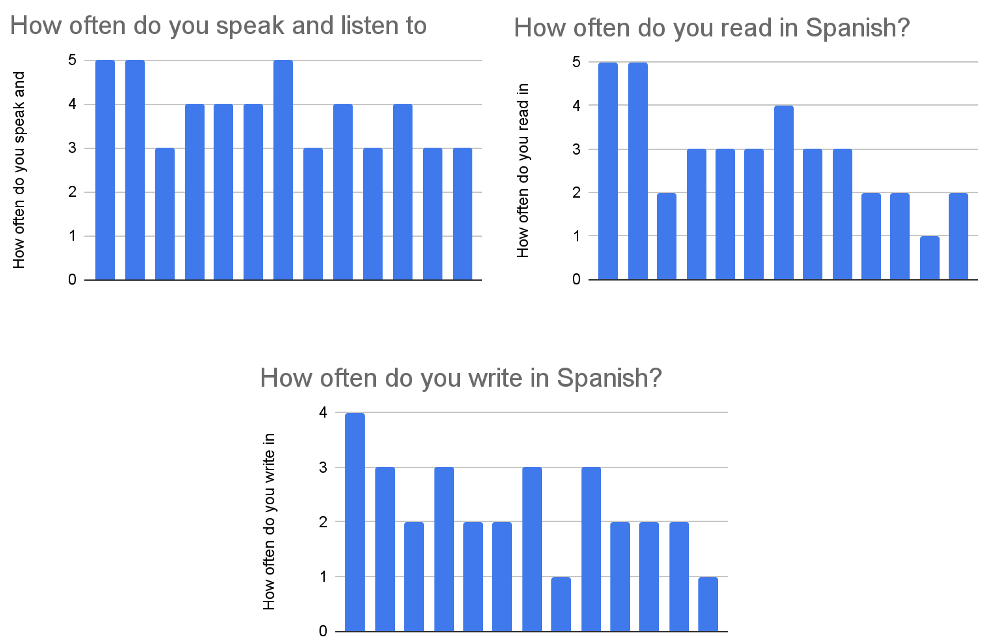

In the aspect of frequency of use, the frequency of speech portion is relatively high but our expectation was for a middling average. The frequency is similar to the perceived confidence in language use which is interesting. The frequency numbers drop in a similar way to the proficiency. The lower confidence level in reading and writing seems to have a correlation to the frequency of use, thus it can be stated that frequency of use possibly bolsters confidence in an area of speech. One note is that the frequency of writing in Spanish is even lower than the confidence level of writing in Spanish.

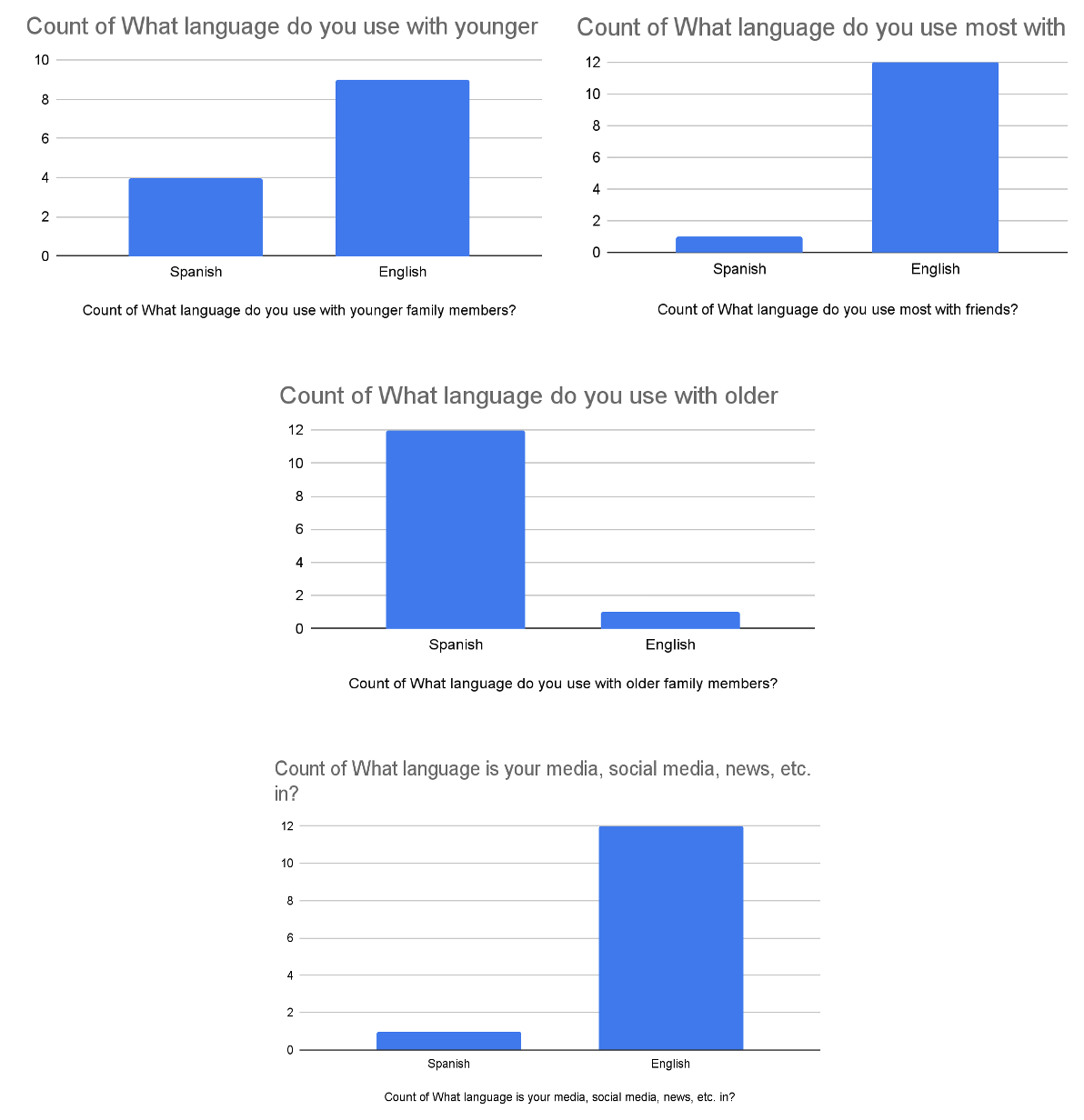

When asked about the social environments in which our speakers use Spanish, the results are extremely stacked in one direction. The language of choice in most instances was overwhelmingly in favor of English. The only instance of the prominent use of Spanish is with older family members. This in a way is logical since the parents’ L1 is Spanish and they would feel more comfortable communicating in the Spanish vernacular of their heritage language rather than English. Even with younger family members, the numbers polled much stronger toward English, but a decent number still spoke to them in Spanish. This information tracks with our hypothesis of attrition, in that English, has the dominant use in their day-to-day language usage. However, this was the only portion of our data to support our claim.

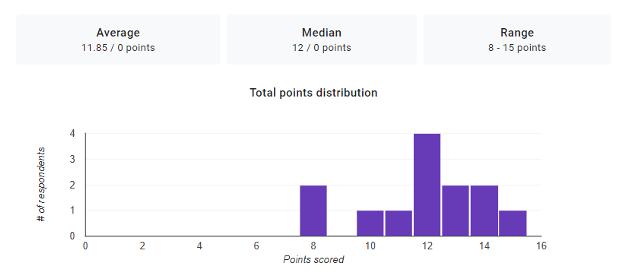

The Spanish reading and writing test proved to predominantly correspond with the perceived proficiency stated in the survey. Eleven of the participants scored ten or higher on a fifteen-question test. The most common score was twelve out of fifteen for four participants. Scores thirteen and fourteen account for another four participants.

One strange observation is the two outlier scores of eight correct answers. Upon viewing these tests individually, some seemingly simple mistakes were made, and for some, the commonality was a bit of struggle on the correct past form to use. One explanation could be a rushed test taker not completely reading the question upon answering, but this is not confirmed. The case of the incorrect past forms is a small commonality of about two questions incorrect on it. Here the participants had a hard time distinguishing between the preterit or the imperfect forms. The reason we believe that the test was rushed is that the clues to use imperfect are usually with the text, and if the text is not fully read, then the reader may not be alerted to use the imperfect. These two participants also missed some easy questions that a beginner Spanish learner would get correct, let alone a heritage speaker. There is no real way to truly claim that a rushed test is the reason for these outliers, but from the evidence presented, this may be the likely case. This also calls to question our methods, as they may be too long for participants to where they may rush through the test and skew our results.

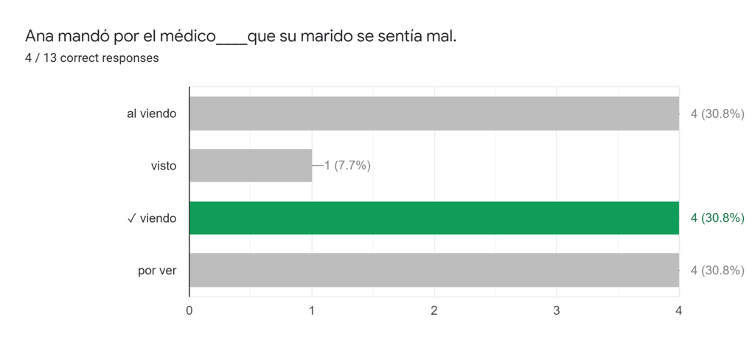

Ultimately though, our participants exceeded our expectations in terms of testing. The test results produced were higher than expected with only our two outliers being in the middle. Even the questions that were wrong could be argued to be fully grammatical depending on the variety of Spanish used as this is a prescriptivist Spanish test. They did however struggle with a particular question pertaining to the present progressive, and whether or not to add a preposition. This phrasing is more typical of formal written language, rather than spoken language. There is a lack of a present progressive trigger word like “estar”, making this even more marked.

The final portion of the test was an optional interview portion asking about participants’ scores, many of whom responded with comments about living in the Los Angeles area and seeing Spanish in their environment. Linguistic landscape has played a large role in the test results according to our participants. Many of them are subjected to many forms of written Spanish stimuli in their surroundings due to the large Spanish-speaking community in Los Angeles. This was not taken into account when planning our experiment but gives us a good idea as to why our data concluded the way it did.

Discussion

Foremost, our biggest flaw was not taking the linguistic landscape into account for our project as a whole. Our early results were strange when first testing, we could not predict just how well our participants projected and performed. Our interview portion really shed light on our shortcoming of neglecting such an influence on heritage speakers in this area. That being said, if we were to do another experiment and frame a comparison against heritage speakers in a less optimal linguistic landscape where English is dominant. We believe that the results would be a staggering comparison as to how much the linguistic landscape plays a role in the limiting of attrition.

We believe that our method format was extremely solid in terms of the quality of data produced, however, the length of a survey, a test, and an interview severely limited the amount of people willing to participate. To some degree, we believe that it even affected our test results. The outliers in our test data suggest that two of our participants may have been speeding through our test without fully reading the questions. Even leaving the interview portion optional, the sequence of google form after google form has given us some unintended consequences.

But to the credit of the long format, the interview portion was eye-opening and put our entire experiment into a better perspective. Three comments describing aspects of the linguistic landscape were pivotal in understanding the prior results. However, the interview also highlighted the flaw of overly prescriptivist language use in our test. The comment that our test was too “Spain Spanish” was something that we knew would come up, however, there is no known formal test that we know of which would test for specific dialects. I believe that we do not have enough credibility as linguists to create this, but for other linguists moving forward, dialect-specific tests may be a useful tool.

Another issue that we observed was the inconsistency of heritage speakers with prior formal education in Spanish. In hindsight, we should have included several questions in the survey asking specific questions about their formal training. As for finding exclusively non formally trained heritage speakers, it’s hard to control for, especially since most schools and colleges require a foreign language. Many heritage speakers opt for taking Spanish as their foreign language in school leaving a small number of young adult heritage speakers to pick from to keep the data consistent.

Conclusion

In the survey, our test group projected that their proficiency was fairly high for reading and writing in Spanish, and their reading and writing test results confirmed this. The only evidence in our favor was that English was their preferred language of choice in most social scenarios, but this did not translate into the test data. Ultimately our hypothesis was proven false, as our group exceeded our expectation of proficiency and did not exhibit distinct signs of attrition in their Spanish reading and writing. This also demonstrated that formal education does not have as much of a tremendous role in proficiency in the heritage language as we expected. Thus, it can be concluded that for our group of Los Angeles Spanish heritage speakers, attrition was not present and that our bilinguals have attained high proficiencies in their L1s and their L2s.

References

Elizabeth M. Liew (1996) Developmental Interdependence Hypothesis Revisited in the Brunei Classroom, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 17:2-4, 195-204, DOI: 10.1080/01434639608666271

Goral M, Libben G, Obler LK, Jarema G, Ohayon K. Lexical attrition in younger and older bilingual adults. Clin Linguist Phon. 2008 Jul;22(7):509-522. doi: 10.1080/02699200801912237. PMID: 18568793; PMCID: PMC3128922.

Keijzer, M. (2004). First language attrition: A cross-linguistic investigation of Jakobson’s regression hypothesis. International Journal of Bilingualism, 8(3), 389–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069040080030201

Keijzer, M. (2010). The regression hypothesis as a framework for first language attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13(1), 9-18. doi:10.1017/S1366728909990356

Köpke, B. and Genevska-Hanke, D. (2018) First Language Attrition and Dominance: Same Same or Different?. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 1963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01963

Montrul, S. (2002). Incomplete acquisition and attrition of Spanish tense/aspect distinctions in adult bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5(1), 39-68. doi:10.1017/S1366728902000135.

Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (2007). Bilingualism and attrition. Language attrition: Theoretical perspectives, 33, 1-7.

Surrain, S. (2018). ‘Spanish at home, English at school’: How Perception of Bilingualism shape Family Language Policies among Spanish-speaking Parents of Preschoolers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 1-15.