Theo Chen, Joan Kim, Yoori Kwak, Sumeyye Nabieva

In our study, we explored code-switching and accent hold-overs for Korean-English bilinguals. Accent hold-overs are theorized to happen when a person is code-switching from one language to another, and refers to a lag in the switching of phonological inventories. While a similar effect has been found in processing, there isn’t a consensus on such a phenomenon in production. This has both psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic implications, as it explores both actual language production as well as sociocultural factors that might influence bilingual speech.

We ran a small experiment in which Korean-English bilinguals read off a script to either another Korean-English bilingual or to an English monolingual. Our script included both borrowings and code-switching. We expected that we would see more of an accent hold-over during code-switching when Korean-English bilinguals spoke to each other. However, we found no evidence of an accent hold-over than expected. This is supported by some additional studies on the topic but could also be a result of our methodology and process, as opposed to an actual reflection of bilingualism.

Introduction and Background

Code-switching is a linguistic phenomenon where speakers who are fluent in more than one language quickly change from one language to another while they’re speaking. It’s very common and is often tied to sociocultural factors. For example, a person might code-switch when they need to use a specific word that is cultural and doesn’t have a good translation in another language. They might also code-switch to show others that they are fluent in multiple languages and to connect themselves to a certain identity or heritage (Myers-Scotton, 1993).

We define accent hold-over as the transmission of the phonological system of one language to speech in another language, tied to code-switching. For example, imagine that a person who speaks both Korean and English is talking to a parent in Korean. They might briefly code-switch to English to say a short word or phrase, such as a person’s name or a culturally-related phrase, before switching back to Korean. We would potentially see an accent hold-over as they are switching between the two languages. Because the phonological systems, or the sounds present in the language, are very different between Korean and English, a person’s speech might be more accented than their normal speech for a short period of time.

Grosjean (1988) studied this phenomenon, which he called the “base-language effect,” and found that it exists in language processing. When two bilingual people are speaking and one person code-switches to another language, the person listening to them experiences a small lag in processing what they’re hearing. Their brain expects to hear sounds from the previous language, and needs a brief period of time to adjust and switch to the other language. A later study by Grosjean & Miller (1994) didn’t find this in language production, but research has been mixed. Some, such as Olsen (2013), have found this hold-over effect in production, while others, such as Šimáčková & Podlipský (2018), have not. Overall, there hasn’t been much research in this area, and past research has not focused on the impact of a speaker’s linguistic background.

In our study, we will look at how Korean-English bilinguals interact with each other, compared to how a Korean-English bilingual interacts with an English monolingual speaker. Our goal is to investigate how vowel and consonant sounds change (or remain the same) as a person switches between Korean and English mid-sentence. We chose these two languages partially out of convenience, because there are many Korean-English bilinguals in this area, and two of our group members are also Korean-English bilinguals. But we also considered the phonological inventories of the two languages: Korean and English have very different sounds, which could amplify these effects. Going into this experiment, we hypothesized that Korean-English bilinguals would code-switch and show more of an accent holdover effect when talking to a Korean-English bilingual compared to a monolingual English speaker.

Similar to the hold-over effect, Maye et al. (2008) showed that when listeners heard a segment of Wizard of Oz where the vowels were shifted down in the vowel space, listeners were easily adapted to the accent change. The listeners were then able to find a plausible implementation of the shifted accent in other real words. Based on this case study, we can argue that bilingual speakers who hear the hold-over accent in other speakers may be able to use it in their own speech as well, once they are accustomed to the sound changes. However, because our speakers will be reading a prewritten script that is written in both English and Korean, it is possible that the orthography of the script may elicit some accent adaptation (Norris et al., 2003).

More generally, we are also looking at Korean phonetic code-switching when reading Korean words in English sentences. Additionally, other factors that could affect code-switching in this instance include prosodic flow, language dominance, community norms (Myers-Scotton, 1993), and the bilingual’s personal language practices and fluency (Poplack et al. 2020). Poplack et al. (2020), when looking at the phonology of English borrowings spoken by French-English bilinguals, also found that there was a large amount of variation between different groups of consonants, so we will be investigating both consonants and vowels in this experiment.

Methodology

To explore our research question, we ran a small experiment: we gave pairs of participants a script to read off of, and recorded and analyzed their speech. We ended up with two pairs of participants. One pair had two Korean-English bilinguals, both of whom have lived in Korea and the United States and considered themselves fluent in both languages. The other pair had one Korean-English bilingual, who had also lived in both Korea and the United States, and a monolingual English speaker who wasn’t fluent in any other language and had little to no exposure to Korean. We accepted the language background that our participants told us, but a more extensive study should include a language test to formally assess this.

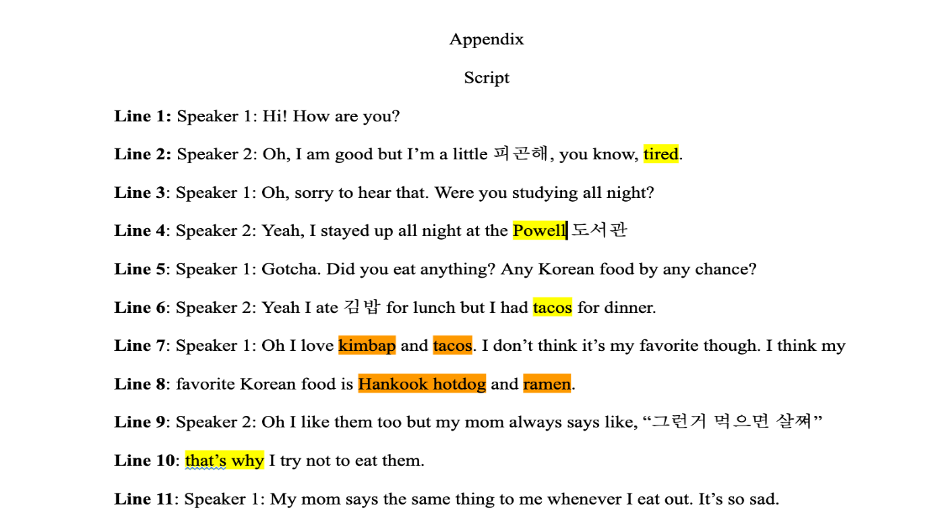

Our script was written by two Korean-English bilinguals, Joan and Yoori. The script had two speakers. Speaker one’s part was entirely in English but had Korean food borrowings: Korean words referring to cultural foods, transliterated into English text because English equivalents don’t exist. For example, we included the words ‘kimbap’ and ‘hangook hotdog.’ Speaker one was designed so any English speaker, regardless of their knowledge of Korean, would be able to read it. On the other hand, speaker two spoke mainly in English but code-switched to Korean. This code-switching was indicated in the script using Hangul, the Korean alphabet, unlike the food borrowings for speaker one that were in the English alphabet. By writing the words in Hangul, we indicated that speaker two should be entirely switching from English to Korean. Then, we could see how these mid-sentence code-switches changed the speaker’s English phonology and pronunciation.

Analysis ended up being a little difficult for us. We originally wanted to look at the sounds in Praat, but that ended up being unrealistic given the nature and scope of our experiment. Our main method of analysis was listening to our recordings by ear, because we had both English speakers who didn’t have exposure to Korean and Korean-English bilinguals. We looked at the phonological inventories for both languages to make sure we had accurate intuitions and picked out notable segments.

Results and Analysis

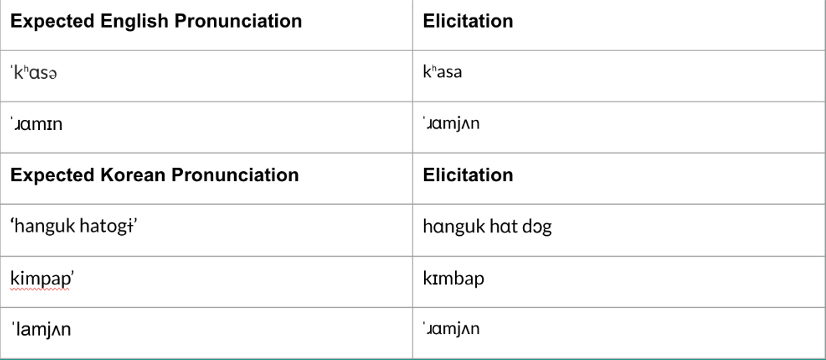

After recording the participants, we listened to the speech by ear. We expected words before and after a Korean word to have an accent holdover. Interestingly, there were no accent holdovers in the words we expected them to be. For example, in line 2 (see Figure 1), the word tired is pronounced [ˈtaɪəɹd] instead of [ˈtaɪjəd]. We also predicted that proper names would contain accent holdovers, such as in line 4 when the participant is asked to read Powell Library, but with the word library in Korean. Instead of pronouncing it as [pa:ul], the word Powell was instead pronounced as [ˈpaʊəl] by both bilingual speakers reading speaker 2 lines. Our script also gave opportunities to pronounce Korean food names, as well as a different nationality’s dish to see if food in a different culture and language would also be pronounced with a Korean accent holdover. We provide this in lines 6 and 7. While both bilingual speakers reading speaker 2 lines pronounced the Korean word kimbap in the proper Korean pronunciation, the word tacos in the same sentence was pronounced in a standard American accent as [ˈtɑkoʊz] instead of [ˈtakoz] as predicted. Interestingly, when the bilingual speaker was reading the speaker 1 script in line 7, the word kimbap and tacos was spoken in an American accent, rather than in the Korean pronunciation. However, an explanation for this would be that in line 7, the word kimbap was written in English instead of in the Korean orthography, possibly causing the bilingual speaker reading that line to have chosen to not read it in Korean.

One thing to note is that when the Korean-English bilingual speaker was reading speaker 1’s line in the script, all Korean food names were read in the standard American accent. For instance, in lines 7 and 8, the words kimbap, hangook hotdog, and ramen were expected to read as [kimpap’], [‘hanguk hatogɨ’], and [ˈlamjʌn] respectively. Instead, the words were elicited as [kɪmbap], [hɑnguk hɑt dɔg], and [ˈɹɑmjʌn]. [ˈɹɑmjʌn] particularly stood to us during our analysis because it appeared to be a combination of a standard American accent and the Korean accent. More specifically, the first syllable is pronounced with the [ɹ] that is not found in the Korean phonemic inventory, but the second syllable is pronounced [mjʌn] as a Korean speaker would.

Another accent incident we noticed was that both bilingual speakers reading speaker 1’s line produced a club’s name in a Korean accent. The club, KASA, or Korean American Student Association, was expected to be pronounced as [ˈkʰɑsə], but was instead produced as [kʰasa] by both speakers.

Discussion

Overall, we did not find any evidence of an accent holdover when bilinguals switched between Korean and English. In every instance of code switching, we observed that the accent being produced changed immediately along with the language in which the corresponding word was meant to be read. The previously mentioned cases that we found (e.g., the case of “KASA”) seem to be instances of code-switching, as opposed to accent holdover. This would indicate that there is no phonological accent holdover effect for bilinguals, reflecting the findings of Grosjean & Miller (1994) and Šimáčková & Podlipský (2018). This suggests a high level of flexibility in language systems and instantaneous or near-instantaneous shifts between languages, as past research has also indicated.

We did, however, have other particularly interesting findings almost entirely unrelated to accent hold-overs. For instance, the words “KASA” and “ramen”, while formed or written in the script in English, were pronounced at least in part with a Korean phonemic inventory. This might suggest that there is a code switch for words that relate to Korean culture or identity, even if they are not formed in the Korean language in the script or in general.

When it comes to accent holdovers themselves, because of a number of limitations, we are not confident that our results definitively demonstrate that accent holdovers do not exist. The small sample size of participants was one, as we only tested one pair of speakers per context (bilinguals speaking to each other vs. a bilingual and a monolingual speaking). The sample size is especially notable due to high variation among bilingual individuals, which means that we may be required to recruit a larger sample size to account for this variability and to be able to construct a meaningful average.

Perhaps our most significant limitation is the fact that the context in which participants had to elicit words was largely unnatural, as it was based entirely off of a prepared script. While it was difficult to find an efficient way to elicit the data we needed for analysis, the scripted nature of elicitation could have affected results in unforeseen ways. Chief among these is the fact that Korean and English have radically different orthographies, which, over the course of this study, often forced us to choose how to spell certain target words such as “ramen”. Therefore, the scripted nature of the experiment might also yield an alternative explanation as to why the word “ramen” was pronounced the way it was: a word originally formed in Korean, it was spelled in its English borrowed version in the script, yielding a potential confusion within the bilingual speaker as to how he ought to pronounce the word he was reading (and therefore an odd code-mix). There is also a possibility that the speakers were conscious of their pronunciation after they noticed that their voice was going to be recorded. This might have made them more focused on pronouncing English words in the English inventory and Korean words in the Korean inventory so that neither their English nor their Korean would sound “butchered” or their transition would seem “incomplete” to the recording and listening experimenters. Considering all of the above-mentioned limitations, our results become difficult to interpret.

Conclusion

Despite suggestions of differences in language processing when it comes to perception of accent change in bilingual speech and code-switching, accent holdovers have not yet been observed in speech of bilinguals to one another, or in speech of a bilingual that is directed to a monolingual. There are several ways the limitations of this particular study could be addressed, but ultimately it appears that code-switching is instantaneous and happens not just on a general word level, but on the phonemic level as well: the inventories switch as much as does the vocabulary. This may illustrate a broader trend in that the multiple languages are placed in the bilingual speaker’s mind as different systems that, even when somewhat mixed (like in code-switching), remain firmly separated.

References

Grosjean, F. (1988). Exploring the recognition of guest words in bilingual speech. Language and Cognitive Processes. 3, 233–274.

Grosjean, F., & Miller, J. L. (1994). Going in and out of languages: An example of bilingual flexibility. Psychological Science, 5(4), 201–206.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Social Motivations for Code-Switching: Evidence from Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Poplack, S., Robillard, S., Dion, N., & Paolillo, J. C. (2020). Revisiting phonetic integration in bilingual borrowing. Linguistic Society of America, 96(1), 126–159.

Maye J., Aslin R. N., Tanenhaus M. K. (2008). The weckud wetch of the wast: lexical adaptation to a novel accent. Cogn. Sci., 32, 543–562.

Norris D., McQueen J. M., Cutler A. (2003). Perceptual learning in speech. Cogn. Psychol., 47, 204–238.

Olson, D. J. (2013). Bilingual language switching and selection at the phonetic level: Asymmetrical transfer in VOT production. Journal of Phonetics, 41, 407–420.

Šimáčková, Š., & Podlipský, V. (2018). Patterns of short-term phonetic interference in bilingual speech. Languages, 3(3), 34. MDPI AG.