Hebbah Elokour, Rowan Towle, Jason Panelli, Frances Vano, Sana Shrikant

This study examines the various factors involved in the maintenance of heritage languages among multilingual immigrant families in the United States. Previous research shows that maintenance of heritage language is a complex and nuanced problem and that most families in the United States fail to pass on their home languages. We sought to compare all factors, and beyond any single particular immigrant family or case. We utilized a survey and several short interviews on which to do analysis. We found that all respondents had a positive outlook on heritage language maintenance and that in 100% of cases those who had advanced language skills had formal language exposure. Furthermore, we found that all respondents had some language skills and continually used them in socially significant ways.

Introduction & Background

Our goal was to study multilingualism in families and the social patterns that are common in failure of heritage language maintenance. We found a significant amount of research on the rates of heritage language retention among immigrant populations around the world. However, the majority of this has been structured around maintenance of Spanish speaking immigrant families in the United States. Also, much of these studies further focus on particular populations such as Cubans in Florida (Lambert, 1996). This is a gap that we wanted to address, as our research contains data points from many different language groups. These studies did give us a good amount of information as to the cause behind heritage language loss, some of which include socio-economic class (Pearson, 2007), education level of family (Bill, Hernandez-Chavez & Hudson, 2000), and perceived social status of heritage culture/language by local society (Kloss, 1966). However, some of these studies have varying results, which makes it difficult to take away one consistent conclusion. Additionally, none have compared all these factors across different immigrant populations of various status and locations to find the commonalities that might exist among the specific low heritage language maintenance group. We took this information as a starting point, and decided to aggregate all of our data points to make a full comparison. With the increase in positive attitudes toward ethnic diversity in the United States (Budiman, 2020), there seems to be a shift underway that could impact the maintenance of heritage languages and culture in both multigenerational immigrant families in the country and families who may immigrate in the future. Our study aims to observe these factors in low heritage language maintenance families and understand commonalities in this group. We hypothesize that younger people will have a more positive outlook towards heritage language acquisition, but we also hypothesize that this will contribute less to language maintenance than factors such as formal education and language use outside of the household. Additionally, we hypothesize that code switching does not occur in these families but that they may pass on small bits of language, like vocabulary that allows them to communicate things in particular social situations, such as when they want to talk about something they want to keep private while not at home.

Methods

A short survey was the primary method of data gathering. These surveys were sent to friends and classmates who are bilingual or multilingual adults and come from bilingual or multilingual homes. The surveys will attempt to understand the heritage level of heritage language mastery, methods of learning in the family, knowledge of English among older members of the family, living conditions, and other questions to assess attitudes towards heritage language maintenance and enthusiasm towards the heritage culture and ethnic identity. There were five yes or no questions and six short answer questions for individually specific information such as language(s) and exposure type. Following this, a short interview was conducted with three survey participants and one of their parents each. This was to get a more in-depth description of particular social and family factors that impact motivation and need to acquire the heritage language. After we collected the data, we measured the level of heritage language competence and in what ways, types of informal and formal exposure, and level of necessity of the language in the family environment. We then analyzed the data to identify common social and speech patterns in groups with low language maintenance.

Key Words

Active Language Skills: This term refers to skills with a given language that amount to some amount of active conversational ability or working proficiency.

Passive Language Skills: This term refers to abilities with a given language that amount to some understanding and ability to use the language in socially specific circumstances.

Heritage Language: This term refers to a language that is spoken by an immigrant family that is not the dominant language in the society in which they now live.

Formal Language Exposure: This term refers to exposure to a language that is purposeful and deliberate such as classes, school, guided reading, and/or cultural events focused on language.

Informal Language Exposure: This term refers to exposure to a language that is random and without specific purpose such as family speaking at home, presence in a larger speaking community such as a neighborhood, and/or random exposure to music and media of the language.

Findings

Our data included 18 respondents to our questionnaire and 3 interviewees. There may be some bias toward specifically individuals exposed to Tagalog as a significant portion of our respondents (7 out of 18) and interviewees (2 out of 3) described Tagalog in their responses. One interview was conducted in person, one interview via zoom call, and one interview through email. These data points are the basis of our findings, and while a more diverse data set and more speaking interviews would have been preferred, this is what was accessible to us due to the pandemic and time zone constraints.

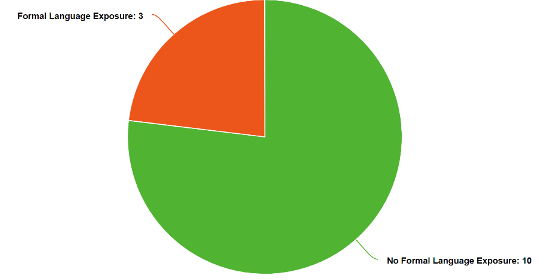

There are two significant correlations uncovered in the questionnaire that may reveal important social factors regarding language acquisition. Firstly, every single respondent with active language skills also had formal language exposure. Conversely, of the thirteen respondents to not have active language skills, only 3 of them had exposure to the language in a formal setting.

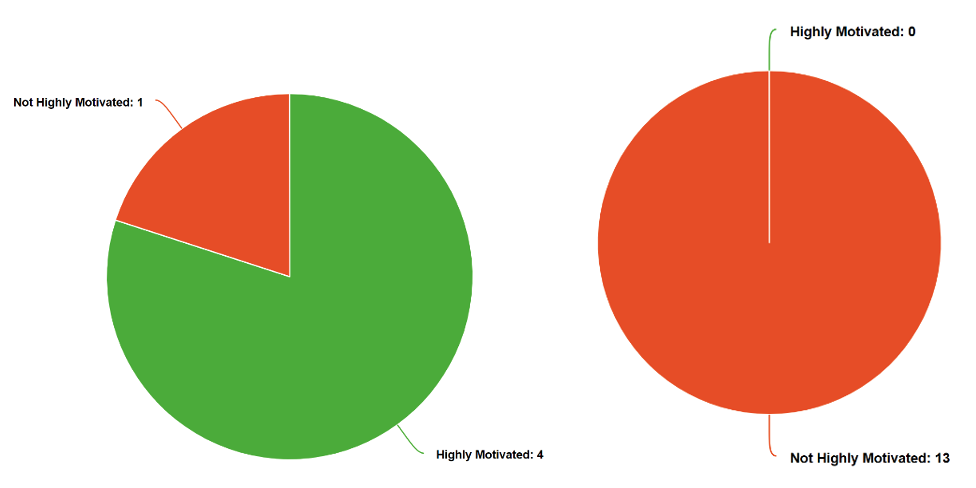

The other highly correlated response to the questionnaire was the descriptions of motivation for the respondents to learn the language. All 13 respondents with only passive language skills either described their family as not motivating language acquisition or presented some roadblock to motivation. This included situations where only one parent spoke the language and thus hindered the overall family motivation for the children to also learn the language. On the other hand, 4 out of 5 of respondents with active language skills presented some necessity in understanding and using the language. In many of these cases, respondents described family members who did not speak English such as their grandparents, and a need to speak and understand the language to communicate with these family members.

The last piece of data from the questionnaire revealed an overarching positive opinion of bilingualism and multilingualism. Every respondent except for 1 thought of bilingualism or multilingualism as a positive thing. The one respondent who did not have positive views of bilingualism or multilingualism described their viewpoint as “Neither positive nor negative”. Additionally, every respondent said they would want to pass on the language to their children if they could. This indicates that sentiment about heritage language learning was positive, even in cases where the respondents had only passive language skills or limited vocabulary and gives little prediction into whether a child will acquire the language with active skills.

The interview allowed us to observe how the interviews used their limited language skills in their everyday life. All 3 interviewees described their language skills as “limited vocabulary only” but still made significant use of the language. Namely, all interviewees were able to immediately recognize the language when hearing people speak it. They all had limited vocabulary as they described and some of the terms and phrases common amongst all of the interviewees included food items and common greetings. More significantly, however, is that all interviewees actually used the language in certain social situations with their family members. The first interviewee’s younger brother refers to her as “ate” or “older sister” in Tagalog, and despite not speaking Tagalog she is uncomfortable with him referring to her by her name. The second interviewee described using the language “strategically” in disguising some sensitive vocabulary in public. This included describing items as “cheap” or “expensive” while shopping to not offend the clerks or describing the physical appearance of someone. The last interviewee described their family using Spanish to ask for favors from each other. The family viewed Spanish as more formal and a more polite and effective way to ask something of each other.

Combining these findings, we learn that the strongest correlations are found in active language skills being present with highly motivated families whose children were exposed to language in formal settings. Conversely, members of the group without active language skills only had very low formal language exposure and did not have families that highly motivated language acquisition. The passive-only language skills group all seemed to acquire some level of the language and all interviewees still used the pieces they knew in socially significant manners. From these findings, we can predict that the informal language exposure in the passive-only groups still had social meaning to this group and even low levels of language acquisition are often used in socially specific tasks. In other words, informal language exposure in families with low motivation to pass on their language still resulted in the language being a part of the way they speak and interact with other members of the family. Particularly, the language is often leveraged for specific social tasks and part of the speech patterns of the family even when the dominant language is not the heritage language.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we conclude that a child’s educational environment plays the most significant role in failing to pass down languages. Even when parents wanted to pass down their native language, the primary language spoken in the host nation’s environment interfered with that goal. Unless some form of formal language education was pursued by the family. Additionally, children who grew up in bilingual households retained culturally significant words more than they did with other general words. These types of words include food and words related to etiquette in the culture. Lastly, the people we surveyed generally had a positive outlook on multilingualism and would want to pass down their heritage language if they could.

To expand our study, we suggest studying heritage learners who grew up not just in multilingual households but multilingual communities. In our research, almost everyone we surveyed grew up in predominantly English-speaking communities. We are interested to see whether or not we’d be able to see different social patterns that contribute to the lack of maintaining a heritage language had the children grew up in multilingual communities. We also suggest finding people who learned a second language in only formal settings and comparing their retention rate to that of a person exposed only in informal settings. Furthermore, a more comprehensive study in the United States tracking social and educational factors across all immigrant communities might further shed light on the strongest factors affecting heritage language maintenance. Our study aimed to answer some of the many questions posed to understand the social implications of multilingualism.

References

Bill, G., Hernandez-Chavez, E., & Hudson, A. (2000). Spanish home language use and English proficiency as differential measures of language maintenance and shift. Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 19, 11–27.

Budiman, A. (2021, April 28). Americans are more positive about the long-term rise in U.S. racial and ethnic diversity than in 2016. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/01/americans-are-more-positive-about-the-long-term-rise-in-u-s-racial-and-ethnic-diversity-than-in-2016/.

Kloss, H. (1966). German-American language maintenance efforts. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Language loyalty in the United States: The maintenance and perpetuation of non-English mother tongues by American ethnic and religious groups (pp. 206–252). The Hague: Mouton.

Lambert, W. E., & Taylor D. M. (1996). Language in the lives of ethnic minorities: Cuban American families in Miami. Applied Linguistics, 17(4), 477–500.

Pearson, B. Z. (2007). Social factors in childhood bilingualism in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 399–410.